I’ve done a ton of post about Bart Beaty’s writing — but I think this will be the last. No promises though!

Anyway, I read Beaty’s book Frederic Wertham and the Critique of Mass Culture recently. In general I found his argument quite convincing — that argument being that,

(a) Wertham was not a monster, and that his good works — such as providing clinical services in Harlem and providing key evidence to support Brown v Board of Education — more than outweighed his negative impact on the comic industry, and

(b) that negative impact has been seriously overstated anyway, and has been used as an excuse to neglect other more important reasons for comics decline — like television.

Anyway, as I said, Beaty largely convinced me. I was interested, though, in one paragraph towards the end of the book in which he is actually criticizing Wertham. Beaty says he disagrees with Wertham about the divide between high culture and low culture, and about the clear superiority of high culture. He argues that the privileging of high culture has hurt America — and he adds that “it is high culture that has most aggressively championed the conservative culture of individualism — often through the figure of the artistic “genius”— against more inclusive and progressive social possibilities.”

To back up this claim, Beaty says this:

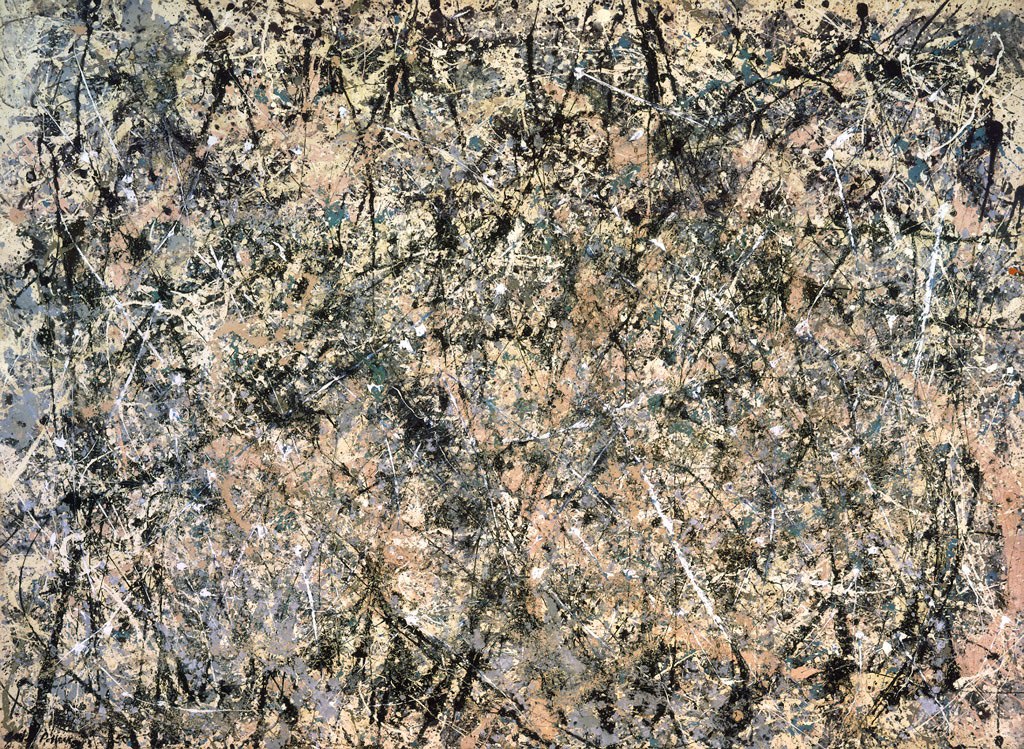

It is no coincidence that at the time of the comic book controversy the Central Intelligence Agency was funding international touring exhibitions of American modernist art that had been championed by conservative critics such as Clement Greenberg and Dwight MacDonald. Art, the product of a individual creative expression, existed in the postwar period in opposition to mass cultural kitsch, and the celebration of art acted as a hegemonic force in American culture. Wertham did not recognize this fact, and consequently his writings played into the burgeoning ideology of individualism that he otherwise rejected.

Sounds reasonable. Except…well, I just recently read Justin Hart’s Empire of Ideas, about US efforts to influence foreign public opinion. I’ve got a forthcoming review of Hart’s book, so I’m not going to discuss it at any length here, but I did want to highlight a passage about the State Department’s support for abstract expressionism. As you’ll see, Hart’s take is pretty different from Beaty’s.

Stefan then flashed up slides of paintings from a well-reviewed, but highly abstract, show of modern art the State Department had put together for an international tour. “Mr. Benton, what is this?” Stefan barked out. “I can’t tell you,” Benton replied. Stefan continued: “I am putting it just about a foot from your eyes. Do you know what it is?” After Benton repeated that he would not even “hazard a guess of what that picture is,” Stefan scolded him: “You paid $700 for it and you can’t identify it.” Stefan closed his examination of Benton by quoting from a letter he had solicited from one of his constituents, a mural painter from Shelby, Nebraska. The artist from Shelby called the exhibit the “product of a tight little group in New York,” neither “sane” nor “American in spirit.” When Stefan asked Benton whether the exhibit depicted “America as it is,” Benton responded: “that was not the purpose of the art.”

Benton’s rejoinder entirely missed the most important point. The State Department, playing its role in supplementing private cultural exchanges and conversations, put together an art show to counteract what policymakers perceived as the contemptuous attitude of foreigners toward American culture. In so doing, they emphasized certain aspects of American art (abstract expressionism), while largely ignoring others (folk art and mural painting). Benton and his staff made a calculated, strategic judgment about how best to capitalize on American culture to

enhance the nation’s image, but this was an inherently political activity, subject to endless debate about who should speak for America and what they should say. In this particular case, Stefan had the last word when the House voted to slash all funds for public diplomacy from the State Department budget.”

For Beaty, high art was a conservative hegemonic discourse, supported by the US government, which contributed to the dominant American discourse of individualism. But Hart calls virtually all those assumptions into question. The US government did support AbEx — but it did so not to impose hegemony on the US, but rather to impress other nations. Moreover, it was attacked for so doing by conservatives, who successfully (hegemonically?) torpedoed future efforts in this direction. The reason they did so was precisely because of the discourse of individualism — to them, in fact, “individualism” of this sort seemed insane and foreign — or, if you will, un-American. The conservatives probably, Hart suggests, would have preferred folk art (though probably not mass culture art like comics.)

This doesn’t mean that Beaty is wrong, of course. Power and ideology are complicated things; there could easily have been contexts in which AbEx proponents were hegemonic, just as there are perspectives from which a classic liberal like Dwight MacDonald could be seen as conservative.

My point though is that, as I’ve mentioned before, I think Beaty — and comicdom in general, to the extent that there is such a thing — can overlook the extent to which relationship between comics and high art is not antagonistic, but parallel — or, rather, perhaps, the extent to which is it antagonistic because it is parallel.

That is, Beaty is certainly correct that AbEx enthusiastically promoted the ideal of individualism and the unique genius. But I think he misses the extent to which it promoted that ideology not out of untrammeled hegemonic power, but rather as a reaction to it’s own unstable and nervous position — an unstable and nervous position not that far divorced from comics’ own. The cult of individualism in AbEx is a way to justify the painting’s worth..and that justification was needed precisely because a lot of Americans viewed AbEx with a lot of suspicion. That suspicion was different in specifics than the suspicion directed at comics (i.e., arty farty nonsense vs. a danger to children) but I think you could argue that in many respects it was similar in structure and in effect.

If this is the case, Wertham’s assault on comics wasn’t because he failed to see the hegemonic power of high art. It was because he knew well that high art was not hegemonic. He was championing high art because he felt that it needed champions — and one way to so champion it was to point out its distance from bad art (just as comic strip creators distanced themselves from comic books.)

This discussion also, maybe, calls into question some of Beaty’s discussion of individualism. I actually agree that the cult of the genius is deployed against more inclusive social responsibilities in art. But it’s useful to realize that those more inclusive social responsibilities vary widely depending on where you’re looking. They could mean helping the poor and creating a more equitable society. But they could also mean — as just one for instance — a loud and intolerant xenophobia. Or they could mean denouncing homosexuals, which Wertham certainly did. Getting rid of the high/low binary doesn’t necessarily lead to progressive results, and it certainly wouldn’t necessarily lead to artists, high or low, throwing off hegemony, and/or hegemonies. Individualism shouldn’t be trusted, but social responsibility has its downsides as well.

Painting attributed to Irv Novick

Greenberg was a conservative? What? Part of his issue with kitsch was that it was fundamentally conservative. I don’t know that one can really call MacDonald one, either. Individualism doesn’t belong to the right. That’s nonsense, unless you use a real limited definition (e.g., individualism as proposed by conservatives).

Maybe Bart means aesthetically conservative instead of politically conservative? Anyway, maybe I’m wrong, but I smell academese of the Bowling Green kind here.

I guess Beaty meant aesthetically conservative? Honestly I wasn’t sure; MacDonald isn’t politically conservative by the standards of his time, I’m certain. But again, these terms are relative to some degree.

I agree, too, Charles, that individualism isn’t conservative. You could argue that it’s classically liberal…but by that definition, Democrats and Republicans are both liberal, too.

And Domingos…I don’t get the Bowling Green ref, no doubt because I’m dense. Could you explain?

Well, Noah, you just need to go to the University’s site to find out. What they call popular art is the vanguard while high art is conservative. It’s the exact opposite of how communists saw things (you just need to read How to Read Donald Duck to find that out). Maybe this reversal also helps to understand how liberals are called “conservative.”

This is a better link.

This is a better link.

That’s a good point, Domingos. Greenberg, just like Adorno, wasn’t defending tradition, but the avant-garde. I believe the same could be said of MacDonald’s attack on the midcult, too. That was hardly conservative, aesthetically or otherwise, at the time. I have a hard time believing it’s even particularly conservative today (try to find avant-garde composers being used in advertising or popular culture — other than horror films, of course).

And, yep, Noah, that liberalism even extends to certain varieties of anarchy, too.

I had a lot of issues with Beaty’s defense of Wertham, namely the way he uses his good acts to excuse the bad ones. Wertham was a critic of the type of thinking, the conservative groups and the like, that he used to spread his censorious views. I read the book when it came out, though, so I’d have to go back and look for examples.

A strong and focused little attack, and I can only “ditto” what Charles and Domingos have already added to it — particularly Charles’s comments about Clement Greenberg and the nature of post-war anti-communist liberalism.

The Greenberg of “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” was explicitly of a more leftist and (American) Marxist stripe that the Greenberg who broke ranks with “The Nation” and was a central voice at “Commentary.” But that anti-Stalinist shift only places him alongside such thinkers as Trilling, Niebuhr, and Hook.

It also seems untenable to say that Greenberg was representing a “conservative” strip in cultural criticism in 1950 by promoting Pollock, de Kooning, Hoffmann — when such “extreme” art was being debated and practically lampooned in the pages of, say, “Life” and “Time” magazines. If this is conservative, then what aspects of American culture could one say that they are conserving — as in opposition to what other voices?

I have not read Beaty’s book, but given you presentation, Noah, there is only one of your sentences with which I can disagree: “This doesn’t mean that Beaty is wrong, of course.” I’m thinking that just maybe it does.

Well…you should probably read it, Peter. It’s really good, I think — a lot of thoughtful points, and I do think he’s basically right about Wertham, though obviously there are bits that I disagree with.

It sounds like the bit about Greenberg, etc., being conservative is even weirder than I thought. I do wonder what he meant by it. The truth is trying to map these aesthetic issues onto conservative/liberal seems largely pointless to me in a lot of ways, at least without a fair bit of explanation.

Yes, I did just mean wrong on this topic, the one you address.

And perhaps it’s wrong for failing to do the very thing that makes seems to mane the other chapters, apparent, so salutary — namely, by failing to look beyond a caricatural progressive/conservative, good-guy/bad-guy image of the figures and events.

That’s my take, admittedly looking from the outside of the outside of the outside of Beaty’s argument. But unless your presentation is skewed, Noah, the problems you present seem pretty severe. Again, at least in that section.

Oh, and Domingos — Beaty is absolutely a cultural studies guy. He’s quite upfront about it…but yeah, he absolutely wouldn’t see eye to eye with you on much.

Oh, I don’t know!? There are two Beaty’s: the comics reader and the academic. I agree with the former when he likes Fabrice Neaud or Edmond Baudoin (I mean the Beaty of Eurocomics for Beginners, even if he’s too fond of what is known as “la nouvelle bande dessinée” for my taste)… And there’s the academic who has to follow trends in Academia.

I’m starting a petition to get Irv Novick’s masterpiece hung in the National Gallery of Art. His seminal depiction of Talia Al Ghul deserves to be hung alongside Raphael’s Cowper Madonna.

That’s the spirit, Suat!…

The main thing here is that only narratives can have political values. “The masses must revolt” and “the masses are revolting” are both typical leftist boilerplate– both of which I find distasteful, as a left-leaning person. An image. or a signifier, can be claimed by any number of narratives.

I’m trying to parse that Bert…you’re saying that an AbEx painting in itself doesn’t have a political stance; it has to be placed in a narrative (romantic individualist against the deadened weight of conservative convention, for example, or, alternatively, oppressive validated high art hegemony against the vital lumpen authenticity of mass culture.)

Is that what you’re getting at?

Well yes, ditto on comics. Plenty of people have found popular culture permissive and modern and weird. But comics actually have narratives, so it’s easier to score ideology points.

Nobody wants me to go into this, but I find left and right fairly unhelpful as anything other than headings for a list of priorities (poverty left, guns right, etc.). Idealism and pragmatism I think is a more philosophically compelling opposition, but right and left can be mapped on to those every which way.

Coming late to the discussion: I found Bart Beaty’s book to be extremely convincing as far as Wertham himself was concerned. He also succeeded in inscribing Wertham in a general history of communication studies, as opposed to positioning him as merely a comic book villain. This is an important book in this respect.

On the other hand, Beaty’s characterization and depiction of the New York intellectuals in general (Greenberg and Macdonald but the others as well) was off the mark in several respect. To give but one example, he includes Gilbert Seldes in the group (p.150), which is highly problematic considering the chronology of his writing, his theoretical feud with Macdonald over the issue of mass culture and the fact that historians and contemporaries never seem to include him in the group.

Describing the NYI and their opinion as hegemonic needs some careful historicization; there is no doubt that they had been moving towards the mainstream in 1954, but the charge is much more convincing if we think of their position in the mid-to-late sixties.

Thanks Nicolas; that’s useful to know.

Not that anyone cares, of course, but…

I give the wrong impression above that I have something against cultural studies. I don’t… I just disagree when trash is considered great art, but cultural studies don’t do that necessarily.

I think “trash is great art!” is a decent shorthand description of cultural studies.

You’re joking, right?

More or less, yes.