In his recent piece decrying the comparison of comics to literature, Eddie Campbell, somewhat surprisingly, argues that it might be better to compare comics to jazz.

By way of a comparison, think of the great Billie Holiday singing “Strange Fruit”. It is a fine literary poem, set to music, and its author could have found no better singer to put it across. But a die-hard fan of Billie Holiday, the kind who has most of her recordings, is more likely to put on something from her earlier Columbia series of recordings, like “You’re a Lucky Guy” or “Billie’s Blues” (“I ain’t good looking, and my hair ain’t curled.”). A good number of the songs she had to sing during that period weren’t particularly good songs by high critical standards, and she didn’t have much choice in the matter, but the important thing is the musical alchemy by which she turned them into something precious. That and the happy accident of the first rate jazz musicians she found herself playing with, such as Teddy Wilson and Lester Young. Every time she sang she told her own story, whatever the material she was working with. I’m not talking here about technique, a set of applications that can be learned, or about an aesthetic aspect of the work that can be separated from the work’s primary purpose. The performer’s story is the essence of jazz music. The question should not be whether the ostensible ‘story,’ the plot and all its detail, is worth our time; stories tend to all go one way or another. The question should be whether the person or persons performing the story, whether in pictures or speech or dance or song, or all of the above, have made it their own and have made it worthy.

The truth is that this analysis is a little garbled. “Strange Fruit” is a mediocre song in no small part because the lyrics are lugubrious — the song’s lurid imagery and emotion sink into a clogged and ponderous earnestness. On the other hand, while it’s true that some of Holiday’s early sides weren’t especially great lyrically, many of them were. She sang “Summertime,”by Gershwin, arguably one of the greatest lyrics in the American songbook. She sang “A Fine Romance,” which means you get to hear Billie Holiday declaim, with great relish, “You’re calmer than the seals/In the arctic ocean/ At least they flap their fins/To express emotion.” She sang “St. Louis Blues” and “Nice Work If You Can Get It”. And, again, even a piece of fluff like the song “Who Wants Love?” is, in its simple unpretension, a good bit better lyrically than the overwrought “Strange Fruit.”

In other words, Campbell takes one of Holiday’s worst written song, declares it one of the best written, and then says that other tracks were better despite the writing rather than because of it.

But be that as it may. Let’s take Campbell’s contention at face value. We can look at “Who Wants Love?” which, as I said, doesn’t have especially great lyrics. “Love is a dream of weaving moonbeams in patterns rare/Love is a child believing/Stories of castles in the air” — that could be worse, but anytime you’re comparing love to moonbeams and having children build castles in the air, you’re not exactly in the realm of great poetry. So I think it’s fair to see this as an instance of a great artist trying to make mediocre material her own.

Campbell in his discussion seems to be suggesting that the content of Holiday’s songs is entirely beside the point; that the story, or lyrics, can be put aside, and the song can become purely about the artist’s achievement. But the achievement isn’t separate from the content…and Holiday doesn’t ignore the lyrics, or their slightness. Rather, her performance is in no small part about acknowledging and using the nothing she’s given. In her first words, she draws out that title, “Who wants love?”, putting more weight on it than the offhand phrase can bear — and so suggesting an intensity that can’t be contained in the song. That’s continued throughout; her exquisite sense of timing — swinging phrases so they stretch out against the beat — doesn’t ignore the song so much as emphasize her distance from it. She doesn’t mean what she’s saying, because what she’s saying doesn’t have enough meaning — not enough joy,not enough sorrow, not enough life.

The slightness of the song, then — its weak writing — becomes, for Holiday, a resource. And, as such, the weak writing is no longer weak. Holiday makes the writing mean more than the writer meant; it is not, as Campbell says, that she is telling her own story whatever the words say, but rather that her interpretation of the words is a great story. Campbell suggests that the song is not literary, but that Holiday makes it great anyway. What I’m saying, on the contrary, is that part of how Holiday makes the song great is that she transforms the words into great literature. And again, she does that not by ignoring what the words tell her — not by eschewing the literary — but by paying closer attention to what the words are saying and doing than the writer did, or than almost anyone can. Holiday’s triumph as a singer is in no small part her triumph as a reader — and as a writer. To deprive her of her literariness is I think in no small part to denigrate her art.

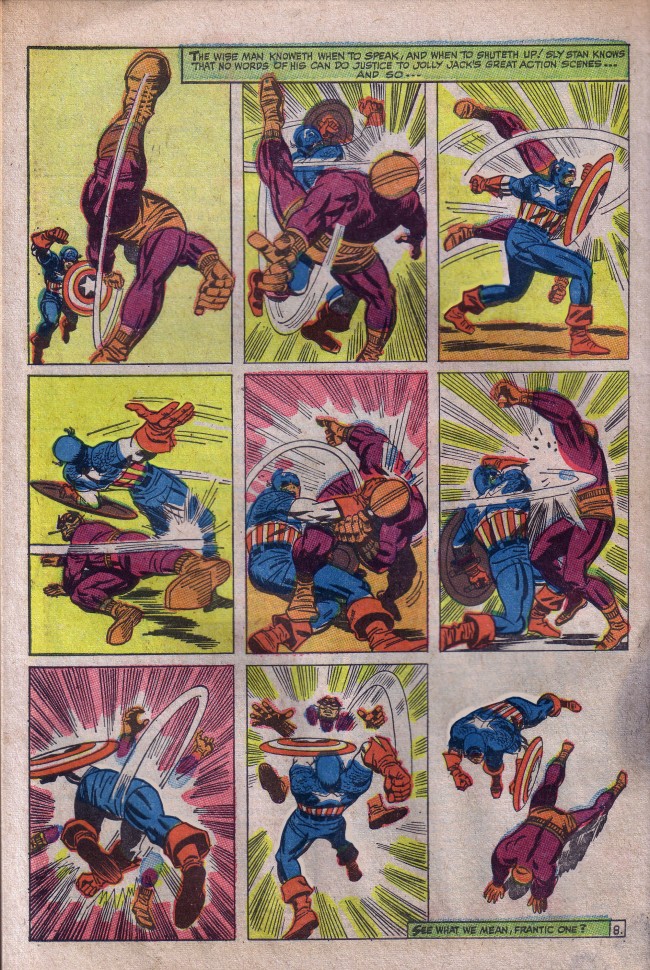

So let’s turn now to the Stan Lee/Jack Kirby page that Campbell presents as an example of counter-literariness and “improvisation” — a word that, coming as it does shortly after the discussion of Billie Holiday, can’t help but suggest jazz.

Campbell argues that this page is shaped importantly by the fact that it used the Marvel method. The art came first, and then the writing was done afterwards. Thus, Campbell argues, the Lee/Kirby collaboration “tends to elude conventional literary analysis.” For Campbell, the anti-literariness of the page is a result of process, and so the most important aesthetic content of the sequence, its most essential comicness, is dictated not by the creators, but by what are basically commercial logistics.

As I said,Campbell’s fear of, and misunderstanding of, conventional literary analysis reduced Holiday’s achievement. By the same token, his eagerness to place comics formally beyond the bounds of the literary denigrates the conscious artistry of Lee and Kirby. That’s in no small part because the conscious artistry in this page is precisely about addressing the literary.

Like the Billie Holiday song, the page’s narrative is pretty much empty genre default. Holiday used nuance and subtlety to explore the distance between her and her tropes. Kirby, on the other hand, employs stentorian volume to belligerently bash down the distinction between speech and noise altogether. The fight scene occurs nowhere in no space; the actors throwing themselves together in a series of almost contextless poses against a background of expressionist, blaring lines.Towards the end, Batroc starts to disappear altogether into the sturm und drung; his hands floating in an explosion of purple, his body returning to the white space that bore it.

Lee’s captions here, are, then, not mere filligree — they actually show a remarkable attentiveness to what Kirby is doing. As Campbell says, the captions establish additional characters — not just Cap and Batroc, but Jack and Stan, as well as the reader as audience. Moreover, Lee’s winking text boxes present the page not as a narrative about the battle between Cap and Batroc, but as a performance by Kirby (and, indeed, by Lee himself.) Thus, the heroic narrative is not about Captain America’s victory, but about Kirby’s Ab-Ex dramatic self-assertion — not about the triumphant outcome of battle, but about the triumphant rush of forms across the page.

Campbell, then, is right that Lee and Kirby are sidelining the superhero narrative. He’s wrong, however, to see that sidelining as formal or default. It isn’t that the comics form naturally or automatically eschews literariness. It’s that Lee and Kirby on this particular page are, very consciously, eschewing the literary. Campbell is in effect taking the particular achievement of Lee and Kirby, and ascribing it to comics as a whole. It’s like reading Moby Dick and concluding that literature is awesome because it has whales in it.

Moreover, while I think it is right in some sense to say (as I do above) that Lee and Kirby are turning away from the literary, it’s pretty important to realize that that turning away presupposes and requires a quite thorough investment in, and understanding of, the literary and how it functions in their art. In fact, I think that you get a better sense of what they’re doing if you see it, not as pushing aside the literary entirely, but rather as substituting one story for another.

Specifically, Lee and Kirby substitute for the story of Cap the story of Jack. The page is not about Cap’s feats, but — deliberately, insistently — about Kirby’s. Thus, the story Campbell tells about this page — that it is about Kirby and comicness rather than about Cap and his story — is itself a story. And it’s a story that Lee and Kirby are quite aware of, and which they deliberately chose to tell.

Which, since Campbell has raised the issue, brings up the question — how does the story Lee and Kirby are telling compare to the story Billie Holiday is telling?

For me, at least, the answer is clear enough. While the Lee/Kirby page has its virtues, the Holiday song is a much greater work of art. This is again, in large part, because Holiday and her band accept, understand, and then work with, the inconsequentiality of the song. Listen, for example, to the Bunny Berigan solo — all bright, brassy good spirits, until that final, wavering, hesitant dropping note reveals the cheer as a bittersweet facade. Berigan isn’t using words, but he’s absolutely telling a story — and that story is about how what the pop song can’t say is a song in itself. Tied up in the vapid tune, Berigan slips free by acknowledging that he can’t get free — his capitulation, his vulnerability, is his triumph.

Kirby’s insistent triumph, on the other hand, is his capitulation. There is no space in the Batroc battle for vulnerability or vacillation. Instead, the art booms out the greatness of Kirby without qualification — which is a problem inasmuch as the greatness is thoroughly and painfully qualified. The story Kirby is telling may be about his own mastery of form, but that mastery can’t escape from the stale genre conventions — and, worse, seems oblivious to its own hidebound inevitability. If Kirby is truly such a heroic individual, why does the individuality seem to resort to such half-measures? The art seems to boast of its thoroughgoing idiosyncrasy and extremity — but when it comes down to it, it won’t and can’t abandon the by-the-numbers battle for full on abstraction. Why can’t we just have bursts of colored lines in every panel? Why not turn the forms actually into forms, rather than leaving them as recognizable combatants? In this context, Lee’s captions almost seem like taunts, praising “Jolly Jack’s great actions scenes” as beyond words, when they are, in fact, perfectly congruent with the hoariest narrative clichés. The hyperbolic indescribable fight scene is, after all, just a fight scene. Holiday knows and uses the fact that her pop song is just a pop song, but Kirby the uncontainable doesn’t even seem to realize how thoroughly he has been contained.

You could certainly argue that the Batroc battle is more successful than I think it is. You might insist, for example, that Kirby’s struggle with the stupid superhero milieu is a kind of tragedy, and that the interest is in seeing him pull something worthwhile from the dreck. Again, that’s not exactly what I get out of it, but if you wanted to do a reading that told that story, I’d be willing to listen.

Whatever one’s evaluation of Kirby, there does in fact have to be an evaluation. If the point of art is to reveal whether the artist performing a story has made it their own and has made it worthy, then there has to be some possibility that the artist in question has not done either. But Campbell’s refusal to countenance comparison, his insistence that (following R. Fiore) comics are comics and that that is there main virtue, comes perilously close to making the comicness of comics their sole virtue. Comicness becomes the all in all — so that the production method of the corporate behemoth in whose bowels Kirby toiled becomes more important than whatever Kirby was doing within those bowels. In an effort to put Kirby beyond criticism by bashing literariness, Campbell paradoxically ends up elevating the genre narrative, with no way to praise Kirby’s efforts (successful or otherwise) to leave those narratives behind. If literature has nothing to do with comics, then Kirby’s efforts to blow up genre narrative into abstraction and form become meaningless. If Kirby can’t fail, then he can’t succeed, either.

The truth, of course, is that art simply isn’t segregated the way Campbell wants it to be. There is literariness in comics, just as there is rhythm in prose and imagery in music. Artists — even comics artists — don’t fit themselves into boxes. Why shouldn’t a singer or an artist tell stories and think about narrative? What favor do you do them by pretending that they can’t or won’t react to and use the words and the narratives that are part and parcel of their chosen mediums? I like Kirby less than I like Billie Holiday, but both of them are greater artists than Eddie Campbell will allow.

_____________

You can read the entire roundtable on Eddie Campbell and the literaries here.

So, in summation … can one make good hack work?

The answer depends on a “performance” based upon perfect mastery of technical skills … that level of technique where one begins to throw away technique — but only after having mastered it.

And the critic requires equally hard-working eyes to “get” it … perhaps they also need an ideology based upon throwing away all ideology and then … just looking

You can’t look without an ideology attached. There’s no such thing as an innocent look.

“It’s like reading Moby Dick and concluding that literature is awesome because it has whales in it.”

Hee. A damn fine rebuttal.

The lyrics to Strange Fruit share a certain EC/grand guignol quality to them, which I think are pretty good within that arena. They’d probably be better delivered as a blues song, rather than Holiday’s “lugubrious” treatment.

Yeah…I agree with Domingos re the innocent look I think. Though (possibly not agreeing with Domingos) I’m leery of creating a category of “hack work” in particular. High art can be cliche ridden and stupid too…

To me there’s no question that you can have great art anywhere; in pop culture or high culture or somewhere in the middle. I think if you want to make a case for a work as art, though, you need to engage with the work. Making claims for the validity of the medium seems mostly beside the point — or directly detrimental to the point.

It’s not just comics, either. Making claims about the greatness of poetry or the worth of poetry or how poetry makes the world a better place; people say that stuff all the time, and it’s nonsense and should be sneered at. There’s a lot of bad poetry; there’s a lot of good poetry. But the medium isn’t art; it’s just a medium. Lauding the medium is just a way to feel like you’re important or worthwhile without putting in the work to make something beautiful or meaningful.

I have to very strongly disagree with Domingos’ remark that there is no innocent look … that is the essence of his ideology, I suspect.

The good draftsman always looks innocent. It’s the final stage

Great post, Noah!

Re. music this is one of my favorite examples: Malika Ayane has a great voice, but she takes the words at face value while Paolo Conte is being clearly ironic portraying a cynical character.

Charles, that’s a good point re: strange fruit. Maybe Screaming Jay could have pulled it off?

Further clarification … the critic never looks innocent … but the artist does and should. This is the problem that many critics don’t grasp

There’s no outside of the ideology to everyone, critics and artists and everybody else.

Oh, fuck yes! Too bad we’ll never hear that.

The problem with the claim that there is no “innocent look” is that it’s inherently self-defeating. You need to step outside, become innocent — the elusive transcendental ego, or the eye of god — for it to have any validity. Good luck with that.

“There’s no outside of the ideology to everyone, critics and artists and everybody else.”

See?

For instance: the simple fact that an artist uses such an artificial device as linear perspective is ideological as shown many years ago by Erwin Panofsky.

The way an experienced artist looks at a page is completely non-verbal … it is purely visual in grammar and syntax and all that … there is no ideology at this level of looking

there is nothing at all but drawing

and curiously, this condition is what so many ideologies aim for and fail: to look precisely and everywhere at once

In case you’re interested.

Domingos, how does change occur, then? How is it possible to have a counter-ideological idea? How does one oppose hegemony? How do you know what your own ideology is?

Are you saying that drawings don’t convey an ideology?

The above was in response to Mahendra. ~

Chartles: you oppose an ideology with another ideology. It’s the work of the critic to try to find out which ideology is at work in any particular case. The problem, as you say, is that the critic talks him/herself from a particular point of view. That can’t be avoided.

the ideology is irrelevant to the deeper level of the visual language

understand your point about Panofsky but such devices are secondary … in a way, all of this is like saying that a text has an ideology and thus, the precise shape of the letters it is written with must have an ideology.

Charles, you’re presuming that there’s only one ideology, so change is impossible. But if there are lots of discourses, and people are influenced by one and another (or constituted by one and another) then there’s no reason that a person couldn’t oppose one ideology or the other at any given time.

To say that ideology infuses all perception isn’t the same as saying that there’s a single totalizing hegemonic ideology.

No, some do and some can take on ideological readings later on, but I’m questioning your notion of ideological imprisonment. You’re basically positioning yourself on a transcendental plane to make this claim. What does the noumena smell like?

Of course it has.

Oops! Mahendra again!

Charles: “What does the noumena smell like?”

A prisoner who can see the bars of his prison?

I definitely didn’t get from Campbell’s piece that he didn’t think the words in comics were unimportant. Only that they couldn’t be the sole evaluation of their quality–and as critics we should strive to talk about comics in their totality. Our critical language when it comes to comics needs to evolve so we can talk about the medium itself–rather than just parsing out the parts of the medium which we are most comfortable from our experiences talking about. Writing and art aren’t really segregated elements in comics. A comic is these two things fused together.

It doesn’t matter whether a comic is well written or not–it matters whether the comic itself is well…comic’d. That’s how it works as an artistic medium, and that’s where it’s value is versus other mediums.

“you oppose an ideology with another ideology”

That doesn’t get you out of the dilemma: in order to see ideology A and B as both being equally ideological, you have to be in a non-ideological mental space. You’re arguing from a transcendental plane that contradicts your claim.

Additionally, why prefer one ideology over another, then? Both are just ideologies (one isn’t non-ideologically preferable to the other). The only reason you prefer socialism over capitalism is you just happen to have been raised under a confluence of social relations that constituted your current preference. What you can’t do is make a claim that one has better effects or that one is better than the other (because anything you say is merely determined by factors outside of your cognition).

“A prisoner who can see the bars of his prison?”

Once again: the eye of god.

Anyway, I agree that artists aren’t any less ideological than critics for not having thought about ideology while creating art.

Just because something is an ideology doesn’t mean it’s wrong, I don’t think.

The idea that you have to have a view from nowhere to act ethically, or even to act, seems confused to me. We’re not just brains choosing the maximal efficient optimization of our actions. We’re relationships and histories. Why should Domingos’ opinions be dismissed just because they’re embedded in his past?

Sarah, I agree that a comic should be evaluated as a comic; thinking about both the words and images and how they fit together. I think I did that, or tried to, with the Lee/Kirby page above.

Eddie’s piece isn’t very systematic, so it’s hard to figure out exactly what he’s trying to say. But he does seem to reject the idea that comics can be compared to literature, and he also seems leery of talking about the narrative or verbal elements of comics. Finally, he seems to be arguing that there’s a virtuous comicness of comics, which is the main reason to appreciate the form. I disagree with all those contentions, for reasons I try to make clear (for better or worse) in the piece.

Domingos’ claim is that every POV is imprisoned by ideology, can not see outside of ideology: “There’s no outside of the ideology to everyone, critics and artists and everybody else.” Now, either he said that because of ideology, in which case it’s impossible on his own terms to prove his case, or he’s wrong, because he’s making a non-ideological claim. If one can see one’s ideology, then one is no longer trapped by it. Once can disagree with it. Sometimes people can develop criticisms of their own ideologies without having it taught to them by another opposing ideologist. Sometimes people can come up with ideas on their own. I don’t share yours and Domingos determinist ideology, though.

‘once’ should be ‘one’

I don’t know about Domingos…but I don’t see ideology as necessarily imprisoning, any more than one’s body is a prison.

And the idea that you need a view from nowhere to make any truth claim is your ideology, not mine.

Charles: ““A prisoner who can see the bars of his prison?”

Once again: the eye of god.”

Nope. The eye of god would see the bars from outside the prison.

That’s not my view. Saying one can make a non-ideological claim isn’t the same as saying one can make a god-like claim ex nihilo. The former is my view; the latter is what I’m here questioning.

Domingos,

I’m reminded of Charlie Manson: “I’m not the one in prison, man, you all are the ones in prison!” That’s just where your metaphor is failing. The ideological “prison” isn’t a prison if you’re aware of it. Criticizing it begins to dismantle it, places you outside of it.

Sarah: “It doesn’t matter whether a comic is well written or not–it matters whether the comic itself is well…comic’d. That’s how it works as an artistic medium, and that’s where it’s value is versus other mediums.”

What do you mean by “well written”? Are you referring to the script? The words (captions and dialogues)? The plot?

What really matters to me in a comic, besides being well comic’d (drawings, words, page layout, montage, etc…) is exactly what matters to me in any other work of art: was this worth my while or is it just cliché-ridden mindless entertainment? Does it convey sharp insights about an important topic? Does it present a complex view of life? Etc…

Charles: I dismantled nothing. I understand your paradox, but saying that I’m talking from a particular point of view doesn’t mean that I’m destroying that point of view. For instance, when I say what’s a good work of art above, I’m clearly limiting my choices. I’m constructing a “prison,” but we all do that don’t we? As I said before, it’s unavoidable. Anyway, I’m behind all my words so far, but I would be more comfortable talking about subjectivity than using a charged word like “ideology.”

Noah: “I’m leery of creating a category of “hack work” in particular. High art can be cliche ridden and stupid too…”

No one is disagreeing with that, but I’m not comfortable talking about something that I know little about. At least time let us with the best examples of past high art. I imagine that for any Rembrandt there were dozens of really bad painters in his time. On the other hand I like some “Matt Marriott” stories and some of Barks’ stories and lots of Oesterheld stories, don’t I.

“Does it convey sharp insights about an important topic? Does it present a complex view of life? Etc…”

This is, of course, a very subjective, even “ideological” notion of what makes “great art” (or great comics)

” it won’t and can’t abandon the by-the-numbers battle for full on abstraction”

This is precisely what Kirby does in the 70s, as his art gets less and less tethered to reality, and more and more a representation of pure force. I’m thinking of OMAC< in particular — the final page and a half eschew figurework entirely to show stuff exploding, the universe of things in unending, violent conflict. In the world that’s coming, are you ready for the will to power?!

That’s cool to hear. I’ve definitely seen some crazy abstract Kirby stuff, and that seems more or less what he was made for. The stupid plots always just seem to drag him down.

Eric: “This is, of course, a very subjective, even “ideological” notion of what makes “great art” (or great comics)”

Bourdieu says that working class people always want the art they’re consuming to be about something (that’s where I come from). I’m as far as saying that comics are seen as childish and irrelevant by the working classes (even if they enjoy reading them on the newspaper) even more than by the upper classes.

Kantian aesthetics (and aestheticism, escapism, decadence) are more of an aristocratic thing. Especially in moments of crisis for the aristocracy: International Gothic, Rococo, late 19th century.

Going back to Bourdieu I would say that artists themselves had a tendency to Kantian aesthetics during the 19th century because they were enjoying creative freedom after centuries (millennia?) of serving a political or religious role. They were more fascinated by their own trade than by anything else (hence abstraction). It was Dadaism and Marcel Duchamp who changed all that (add politics to the mix and you have a very “working class” contemporary high art today). When mass art became more and more childish taste inverted. It’s mass art that is escapist today, not high art.

Kantian aesthetics: r.i.p..

If a hippie and a super-patriot argue politics, neither of them needs any transcendent plane to be cognizant of the differences between their ideological positions, or to be aware of how their own respective positions represent ideological positions. Ideology is always an intellectual justification that is nowhere near as invisible and ineffable to its proponents as Barthes chose to claim.

The plane that allows them to judge the validity of their own professed positions is going to be immanent, not transcendent: an immanent knowledge of whose ox is gored (or not gored) as a result of real-world ideological applications.

Hey…I sort of agree with that!

That may be a first as far as ideological agreement with gene goes for me….

Domingos:

Yeah I just mean it is irrellevent to the totality of the works effect whether the words elements which would make up the script are in isolation good or not.

What is important is the ccumulative effect of everything in concert. And sometimes certain elements are better than other elements. But it is the net effect which matters. There no primacy beyond what is one the page and in the comic. The thing itself.

Sure. Like I said, I think Billie Holiday works with the fact that the words in “Who Wants Love?” aren’t very good, and makes that a feature rather than a bug. And Lee and Kirby try (with some, though not complete, success) to erase the stupid genre default of their page and overwrite it with an almost high art abstraction.

Where that differs from Campbell’s argument I think is that, (a) he tends to see these manipulations of the literary or verbal as innate to the form (song or comic) rather than being conscious artistic interactions with the literary or verbal, and (b) he in part as a result seems to think that there’s no way to compare comics to literature, or that comics are somehow unique or exceptional as art.

So…I’d disagree that it’s irrelevant whether the words are good or bad on their own. The words and narrative are absolutely relevant, because they’re an important part of what the artist has to work with. That doesn’t mean that a bad poem will make a bad song…but it does mean that one of the ways that the bad poem might make a good song is through the way that the singer/musicians deal with the fact that the poem is bad.

This conversation here reads like you’re not all using the word ‘ideology’ in the same sense.

Also: do the lines in that Marvel comic really amount to Expressionism and/or Abstract Expressionism? Seems like a bit of a stretch.

I think Kirby is definitely playing with having the figures disappear into abstraction, and the abstraction expresses emotion in a way that recalls ab-ex in a pop way.

Briany: in a broad sense ideology is a set of ideas received from one’s culture. I would say that ideology in a more restrict political sense is included in that broad category. It doesn’t matter much to me if we’re talking about racism or capitalism or whatever… everything is politics, right?…

Noah: how do you reconcile your aesthetic reading with the fact that these are just a superhero and a supervillain beating the crap out of each other? Or do you consciously choose to not deal with this content. Plus: isn’t this comic story more than one page? Aren’t you analyzing the page out of context? Since we’re talking about ideology: how about Captain America? We know who he is, but who’s the other guy? A representative of communism? Is this a cold war thing, or what? So many unanswered questions…

The always useful Wikipedia informs me that Batroc is a French mercenary (oh, the always romantic foreign legion!) who is more of a Fascist than a Communist (he worked for Hydra), but he also worked for a foreign power at some point. Hmmm… I wonder…

Well, I talk about both of those things in the piece. I think there’s a fair bit of evidence on the page that Lee and Kirby are deliberately substituting an aestheticized narrative for the superhero battle. So, yeah, I think they’re arguably deliberately erasing the rest of the comic to present a performance of art which is deliberately decontextualized.

but…as I say in the post, I don’t think it’s entirely successful. I think the stupid supehero content isn’t erased entirely, and there’s no real acknowledgement that it isn’t erased entirely, so it ends up undermining the performance. So I’m ambivalent about the page, basically; I like what the’re doing, I think they’re smart about what they’re doing…but I think the genre tropes trip them up in the end.

Noah: Eddie Campbell is not saying comics can’t be compared to literature at all. He’s saying that you can’t remove the comic aspects of a comic, make the comparison, and then conclude that because the comic without it’s comic elements doesn’t stand up to the literature that it is therefore shit.

He is saying that you can’t represent what Billie Holiday does simply by posting the lyrics of the song she has sung. The qualities of strange fruit and whatever other random ass jazz song you want to pick are in the interpretation–the music itself is the thing–not the lyrics by themselves.

He is simply saying that to compare comics to literature–you need your book of words in one hand– and your comic in the other hand. To compare Kirby to Faulkner–you would take the pages of New Gods–put them next to the prose of Faulkner–and that would be the comparison.

It’s the same as if I asked you to to discuss the merits of Pablo Picasso vs. the merits of Gertrude Stein. You would not simply describe the “plot” of Guernica and the plot of Making of Americans–and say “this is not to the standard of that”.

The experience of reading a comic is the relationship of the writing, the images, the inking, the coloring–it’s all of that together and the impact it has when you read it.

I read back through the Campbell article–and I’m more convinced than ever that you’ve misinterpreted his meaning–or extrapolated something he didn’t really intend. Not that that matters–because we’re discussing ideas and not the logical consistencies or inconsistencies of random internet person A.

Again, I’m not sure that the two of you are saying dissimilar things. I think though that you ARE saying something different than NG is saying. And that your response should have probably been direct at him.

At any rate. I don’t really care about EC comics either–but not for weird BS reasons. I just don’t have a huge interest in it–and I think that stuff is being grossly over covered critically–for reasons I can’t completely fathom given the insane amount of things NOT being written about.

Noah, I think your use of ‘expressionist’ and ‘Ab-Ex’ is very inaccurate, but I do take your meaning. The ideographic depiction of force and impact escalates until the baddy is all but subsumed by its explosive power. However, as well as amping up the pyrotechnics, another parallel reason for the elimination of parts of Batroc’s body adjacent to Captain A is clarity enabling a feeling of speed: if all the details of Batroc’s body were included in panels 7 & 8, there would be more of a tangled dynamic (considering the blocking of the figures) and parsing the images would take longer, thus making the panels seem to accomodate a slightly longer stretch of time. This kind of economical multi-tasking approach to simple graphic techniques is, in a way, the essence of proficient cartooning.

Domingos, I wasn’t asking what ‘ideology’ means, but thanks anyway.

When reading the different ways people are using the word in conversation with each other, it seems as if some are employing the Marxist conception, some the post-modern (Althusser) version, and others a much looser definition altogether. The mismatch of usages being applied might well be causing communication breakdown in some places, at least that’s how it looks from where I’m sitting.

Well, I’m okay with disagreeing about what Eddie said, I suppose.

I don’t think Suat removed the comic aspect of the comic. He felt there were weaknesses in the writing, and felt that that mattered. And I agree with that. As I said, the writing and the narrative matter. Creators can do various things with that…but I’ve never really seen anything from, or about, EC Comics that really suggests that they overcome the problems Suat talks about. Eddie doesn’t even really seem to understand what the problems are. Or perhaps he just thinks that comics aren’t, and shouldn’t be expected to be, that good. I think a lot of things he says suggest that that’s the case, actually.

Suat’s whole point, incidentally, was not that EC comics are shit, but that they’re overrated. So I think you actually agree with him about that.

Domingo: “For instance, when I say what’s a good work of art above, I’m clearly limiting my choices. I’m constructing a “prison,” but we all do that don’t we?”

That’s not much of a prison, though, since you’re choosing from options. If you had said that we all make ideological choices, I wouldn’t have disagreed. And I’d have similar problems with subjectivism — that’s just the old form of what might be called ideologism: both lead to a solipsism, with the latter being the preferred, updated collective form.

Noah,

I enjoyed your reading of Holiday’s interpretative abilities, but I don’t find it very convincing as a distinguishing feature on which to evaluate “Who Wants Love” more highly than that Lee-Kirby page. The distinction rests on your belief that she was above the song, thought it was kind of dumb. I wonder if she really had such a view of the songs she sang. I’m admittedly not much of a fan, so I don’t know one way or another. Do you have evidence that she had such a low opinion of the songs she chose, or are you just creating a psychological reading here based on what you think you hear? AND: Even if there is evidence that she held such a view, it’s problematic to rest qualitative distinctions between art on the psychological portrait of the artists. That’s pretty much just the old school intentional fallacy.

Oh, of course. Domingos was clarifying his use of the term. That’s what’s needed. Yes.

Briany,

As I hope it’s now clear, it doesn’t much matter what you call it, I don’t much care for reductive or determinist views of stuff like consciousness or reality. So the minute someone says we’re all just prisoners of language, gender, subjectivity, ideology, etc., I’ll object. I’m just wired that way (harhar).

I’m not resting it on her having a low opinion of the song, I don’t think. Like I said, I think she reads it so closely that it stops being a bad song.

Rather, she’s using and emphasizing the ambiguity in the words. That is, the song asks “Who Wants Love?”; the answer in the song is that no one does, but it of course actually suggests that everyone does. I think Holiday uses that distance — the irony *in the song* — to great advantage, even though the song is weak in other respects. That irony mirrors the distance between the triteness in the lyrics and Holiday’s interpretation of them— but I think there’s a textual cue, if you will, to justify my reading, rather than just imposing it at random.

And, again…the difference is that Holiday’s interpretation is built around distance and irony, so the weakness of the song can become a feature. Lee/Kirby is built on declaring themselves the King loudly…which is fun, but falters on the fact that they’re kings of banality in a lot of ways.

I’m grateful that you read the interpretation and talked about it though. There doesn’t seem like a whole lot of interest otherwise….

Well, that’s a decent defense: but aren’t you claiming that the song isn’t bad in and of itself, though? That Holiday is smart enough of a performer to see what’s intelligent about that song? I guess that raises the question of is a song ever bad or good, but depends on the reading of the performer … and, of course, the listener’s reading of the performer. That’s pretty much Eco’s take on interpretation in the Role of the Reader: the writer says something, the reader says something and the text says something — all are sites of resistance. (The writer here is the performer, and the text is the songwriter and his song.) I’m inclined to think that no matter how great a performer, some songs are such turds, that the result is never going to give us what you were able to get out the current example.

I though Campbell’s complaint was about over-emphasis of the literary, not that he was insisting on a total purge. Who Wants Love has lyrics, and Holiday uses them, but the interesting things said here about the recording are predicated on prosody and other aspects of musical performance with only a passing nod towards anything of literary concern. That’s a very different balance to that which seems to dominate comics criticism in general. I’m a bit of a scopophile so it irks me, but at the same time it’s entirely understandable: criticism is an art which typically takes a written form; it’s done by writers; writers tend to be very interested in literature, its means and methods. Corollary to that is the need (or desire, anyway) for critics of comics (and film) to make special efforts to engage with the medium at the furthest end of its methodological spectrum from that which is their own technical speciality.

Y’know: if all one has is a hammer, one sees nails everywhere.

I really like your reading of Eco’s reading of my reading! And yes, that’s very much what I’m saying — that it isn’t that the song is good despite being poorly written, but rather that part of the success of the song (or of the Lee/Kirby page) is the way that the creators read and write the text or narrative themselves.

I’d agree that some texts are going to resist very strongly — but creators have a lot of resources, I think. It’s possible to flat out mock a text you’re working with (think Screamin’ Jay again).

Not prosody. Sorry. Timbre and melody. Prosody lacks semantic meaning altogether.

The thing is, though, that Eddie’s reading wasn’t particularly attentive to visual elements in comics either, I didn’t think. His readings were very cursory in general, though….

That’s true, it was all a bit oblique, leaning towards meta.

Not really leading by example as much as saying “But look at this! Just look at it!”

Certainly kicked off some thinking, though.

Yeah noah. I agree with suat’s conclusion just not his reasons for arriving at them. I don’t agree with the toolkit he applies to comics. But I already knew that. We had a version of this same debate about heavy metal and druillet.

Charles: options, sure, but a limited range of options. I invented nothing and I doubt that there’s much out there to invent.

Maybe I’m repeating myself, but my main problem with the whole anti literary approach to comics is that either people are referring to words only or they’re co-opting many features to the literary field that don’t belong exclusively there. I mean characters and plot and story and even meaning and ideas and, yes, ideology. All that exists in words and images. I don’t think that Suat criticized words only. So, maybe when one compares a comic with great works of literature we’re just saying that the whole package doesn’t belong in the same league being consequently overrated by the comics status quo.

My theory re. this is that both the comics champions and their biased civilian detractors are right and wrong. The former are right that comics have the potential to achieve greatness, but they’re wrong when they present the pitiful comics canon as evidence. The anti-comics brigade is wrong when they think that comics are childish and stupid, but they’re right when they don’t swallow the evidence given to them. Here are my thoughts on the subject.

It doesn’t make much of a difference, but here’s the real link.

Charles, man, just…you need to just give up arguing with (for lack of a better word) pan-ideologists. There is zero you can say to make any headway against them; for every point you can raise, they have an immediate reply, along the lines of “But that itself is its own ideology”. It’s the intellectual equivalent of the playground’s “I know you are, but what am I?”; this might be seen as either a strength, or a weakness of the position.

BTW, the noumena smell almost exactly like the transcendental apperception of the manifold, only a little bit fruitier.

In school you kids really really got excited when you had to dissect that frog, didn’t you?

Hey Heidi. I like talking about and thinking about art. It’s why I run a blog where folks can talk about and think about art. If you don’t like talking about and thinking about art…then you would have a site more like yours, I guess.

If God didn’t want us to dissect frogs he wouldn’t have given us the hammer.

I actually think dissecting frogs in school is kind of evil. But art isn’t frogs. The metaphor just doesn’t work very well.

I kinda cheer these moments when anti-intellectualism rears its head.

Last night I was listening to the commentary for the Criterion DVD edition of Claude Chabrol’s “Les Cousins.” According to the commentator, Chabrol didn’t believe that a script mattered at all for producing a good film. According to him, anything could be turned into a decent film depending on how one employed camera movements, editing, etc. The thing is, though, while Chabrol made some decent films he also made some stinkers and perhaps not any great ones. So to sum up- no, one doesn’t need a great script or song lyric to make something decent- but it certainly doesn’t hurt.

“I wonder if she really had such a view of the songs she sang.”

Well, she was a comic book reader. One doesn’t need to have critical sophistication to have musical talent. Those are two very different things.

“If God didn’t want us to dissect frogs he wouldn’t have given us the hammer.”

How about both?

All three! (Thor’s a god, right?)

Holiday was a comic book reader? Do you have a citation?

Holiday’s autobiography (co-written with William Duffy, I think) is actually extremely thoughtful and just generally awesome. She comes across as very smart…and able to render the acid critical judgment now and then. I remember her having particularly sneering things to say about the song “How Much for that Doggie in the Window”, for example (which I don’t think she ever sang herself…)

—

https://www.nytimes.com/books/97/06/29/nnp/18627.html

http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/arts-billie-and-lester-against-the-world-1106491.html

Hah! That’s pretty great. I wonder which ones she read? Is there an archive of her papers? Probably not….

One doesn’t need to read books to be mentally sharp. One can be sharp in some things and not in others.

These google books links break up sometimes, so here’s a relevant quote from Michael Denning’s “The Cultural Front: The Laboring of American Culture in the Twentieh Century.”

“…she was not an intellectual. Holiday was a reader of comic books; and Lewis Allan noted that when she first heard “Strange Fruit,” she did not know what the word “pastoral” meant.”

There’s even a comic book about Billie Holiday which is “okay” as far as I can remember. Can’t remember if Munoz and Sampayo show her reading comic books in that one though.

If the police confiscated her comicbooks, as that Independent article claims, there might be a record somewhere.

That’s true, Jones, but I do like ideological criticism, so it’s a way of shoveling the sand out of my hole. You ever read After Finitude? The criticism of what Meillassoux calls correlationist thinking (starting with Kant) is applicable to just about any assertion of our human limitations (“finitude”) by humans I’ve come across, including pan-ideologism. It’s a fun book that’s well-written.

Before I decide if After Finitude has thoroughly de-pantsed Western philosophy, I want to just mention that both Kirby and Holiday are not flawless creators, which is integral to their appeal. All art is outsider art, especially as seen from the cultural-producer universality of now. Holiday sang flat quite a bit of the time, and sounds, in anachrontic retrospect, not unlike Lil Wayne. Kirby distorted bodies grotesquely in the name of mannerist foreshortening all the time. And both of them are easy to impersonate because they are fairly hamfisted purveyors of compulsive tics. And they’re both great. If they were a certain amount better, they would have been forgettable.

Mellaissoux does look interesting, if Platonically arrogant, based on sreading Wikipedia.

Yeah; that’s a great point, Bert. They’re both kind of clumsy creators, and the clumsiness is in no small part the beauty. Which is certainly the case for lots of literature as well. Philip K. Dick’s clunky prose style — or really Dickens’ clunky prose style — or even Henry James’ ridiculously lumpy ponderousness. There’s sometimes this sense that there’s some outside to convention which is weirder or less polished than whatever the thing is that is supposed to be normative or what have you…but really nobody, and no artist, is perfect, and how they deal with or work with their imperfections is always part of what makes art art.

————————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

“Strange Fruit” is a mediocre song in no small part because the lyrics are lugubrious — the song’s lurid imagery and emotion sink into a clogged and ponderous earnestness. On the other hand, while it’s true that some of Holiday’s early sides weren’t especially great lyrically, many of them were. She sang “Summertime,”by Gershwin, arguably one of the greatest lyrics in the American songbook. She sang “A Fine Romance,” which means you get to hear Billie Holiday declaim, with great relish, “You’re calmer than the seals/In the arctic ocean/ At least they flap their fins/To express emotion.” She sang “St. Louis Blues” and “Nice Work If You Can Get It”. And, again, even a piece of fluff like the song “Who Wants Love?” is, in its simple unpretension, a good bit better lyrically than the overwrought “Strange Fruit.”

In other words, Campbell takes one of Holiday’s worst written song, declares it one of the best written…

————————-

…”The Literaries” strike again!

This argument is the exact equivalent of maintaining that Bouguereau ( http://media1.shmoop.com/images/mythology/characters/birth-of-venus-bouguereau.jpeg ) was a far better painter than Henri Rousseau ( http://uploads7.wikipaintings.org/images/henri-rousseau/tiger-in-a-tropical-storm-surprised-1891.jpg ) because of the former’s greater sophistication, complexity of lighting effects and composition, anatomical mastery.

Looking up the “Strange Fruit” lyrics (at http://www.lyricsfreak.com/b/billie+holiday/strange+fruit_20017859.html , where an ad encourages us to “Send ‘Strange Fruit’ Ringtone to your Cell” [!!]), we read:

————————-

Southern trees bear a strange fruit,

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root,

Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze,

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

Pastoral scene of the gallant south,

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth,

Scent of magnolias, sweet and fresh,

Then the sudden smell of burning flesh.

Here is fruit for the crows to pluck,

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck,

For the sun to rot, for the trees to drop,

Here is a strange and bitter crop.

——————————-

I find the lyrics powerful, macabre, affecting, even dissevered from music and Holiday’s voice. Chillingly contrasting the prettified image of the South with the horrors being regularly perpetrated there. As http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strange_Fruit informs, moreover, unlike the brilliantly frothy fluff acclaimed over it, it’s powerfully grounded in a horrendous reality that it protests against.

And, consider: if you wanted to write a song arguing against the horrors of lynching…

http://everyscreen.com/photos_06/LynchingOfThomasShippAndAbramSmith_01.jpg (The expressions on the faces of the mob are the epitome of “the banality of evil”!)

…would complex musicality, wittily sophisticated wordplay á la “You’re calmer than the seals/In the arctic ocean/ At least they flap their fins/To express emotion,” not be…aesthetically inappropriate?

On a similar vein:

————————-

Ng Suat Tong says:

There is an artistic impulse behind “Master Race” but it is vastly inferior to that which we should expect of a master of the form. The constraints of entertainment and commerce have housed the work in mediocrity. No one should consider “Master Race” anything other than an above average cave painting on the path to greater things.

————————-

That last line is awfully telling. Because “Master Race” and cave paintings were followed by work of greater sophistication and complexity (more “Literaries”-type argument), therefore they can be sneered at as mediocrities.

Never mind that even “primitive” work can have plenty of aesthetic worth: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/6/6a/GuaTewet_tree_of_life-LHFage.jpg/220px-GuaTewet_tree_of_life-LHFage.jpg

http://2.bp.blogspot.com/-KWGrdXRRlLc/UEcUMW_e9WI/AAAAAAAAJtI/gDq5eZh7FRI/s1600/Lascaux-hunters.jpg

Compare: http://www.mlahanas.de/Greeks/Mythology/Images/VenusGettyMuseum.jpg

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/19/Venus_of_Willendorf_frontview_retouched_2.jpg

…For all its crudeness, is not the prehistoric work vastly more powerful, intense? A greater work?

About to post the preceding, scrolled down, and saw:

————————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

…They’re both kind of clumsy creators, and the clumsiness is in no small part the beauty.

————————-

That can truly be the case! Indeed, there are occasions (Expressionism, for instance) where a beautifully “non-clumsy” approach would be the wrong approach.

————————-

mahendra singh says:

So, in summation … can one make good hack work?

————————-

In the past I’ve argued against Gary Groth’s slamming of the lesser talents toiling away at the comics mills as “hacks.”

—————————–

hack

3.b. A writer hired to produce routine or commercial writing.

——————————

http://www.thefreedictionary.com/hack

One can labor on a product created for solely commercial intentions, and still take pride in one’s job, strive to make it as aesthetically worthy as time and the task’s parameters allow. And achieve work that has more than passing worth.

But, away from the mundane world, we get pronouncements such as:

—————————–

Ng Suat Tong says:

Truly great art is not shackled by commerce. It is born of a great artist’s insatiable need to create and to tell the truth.

————————-

https://hoodedutilitarian.com/2012/09/ec-comics-and-the-chimera-of-memory-part-1-of-2/

The Romantic ideal of the tortured, brilliant Artist starving in a garret, rejecting all compromise or public acceptance, listening only to the voice of his Muse, yet lives!

Never mind that the vast majority of art by great architects, Old Master painters and composers — who were expected to produce family portraits, religious works, commemorative compositions at their employer’s behest — was “work for hire”…

————————-

Domingos Isabelinho says:

You can’t look without an ideology attached. There’s no such thing as an innocent look.

There’s no outside of the ideology to everyone, critics and artists and everybody else.

————————-

Thus, to oppose ideologically-circumscribed thinking…is itself an ideology!

Cute; I’m reminded of the Inquisition arguing that you’re either with Christianity or allied with Satan; that nothing can exist outside those positions.

Calling Strange Fruit mediocre and acting as if that is a majority opinion is pretty hilarious. It is by no means any kind of consensus that Strange Fruit is a mediocre song. In fact, it’s mostly considered the opposite. And generally considered one of the best songs in the american pop music lexicon. But I definitely agree that if it were to be a mediocre song it would certainly aid the point you’re trying to make–which is of course wildly convenient. You can say that Holiday made better songs(something even Campbell says)–but to stretch that into calling it a mediocre song, just exposes the flaws in your evaluation process.

But…Eddie says it’s not so great as well, or at least that’s my reading. And in fact, he’s the one who argues that it’s generally seen as a lesser song. I don’t say anything about its general critical reception. I just talk about my own reading of it.

I mean, is it just out of bounds to dislike anything Billie Holiday is? She’s just beyond criticism, so the only thing you’re allowed to do is rate her different levels of awesomeness? She was a great artist, but not a perfect one. If I’m willing to say that War and Peace is kind of bleah without people losing their shit, I don’t know why suggesting that Billie Holiday had a duff song should be that much different….

Not liking War and Peace is OK because who wants to be an elitist snob, right? Talk about the status quo!

“In school you kids really really got excited when you had to dissect that frog, didn’t you?”

Before Physiology class started I let my frog go after having caught him the night before. We had too many frogs.

Billie Holiday, greatest voice in music history. ‘Strange Fruit’ most powerful and difficult songs ever written http://lyricsmusic.name/billie-holiday-lyrics/the-billie-holiday-songbook/strange-fruit.html