Once upon a time, there was a bastion of comics criticism which, it has been opined, stood against the hordes of barbarians trumpeting the works of John Byrne, Todd McFarlane and assorted other idolaters of caped beings. But time withers all, and like Saint Gregory of Rome, the rulers of that holy organ negotiated a separate peace with the hordes — the “empire” surviving but now a rotten shambles and a mockery of what it once stood for. It has been said that the purported ideals of that magazine never existed in the first place. That past is debatable, the present less so.

What was once a hotbed of disagreement and debate has now become one of affirmation and boot licking acceptance. The rallying cry heard last week was a sermon to the converted, an affirmation of the god-like status of various revered cartoonists — that their comics remain untarnished by dint of an indefinable comic-ness

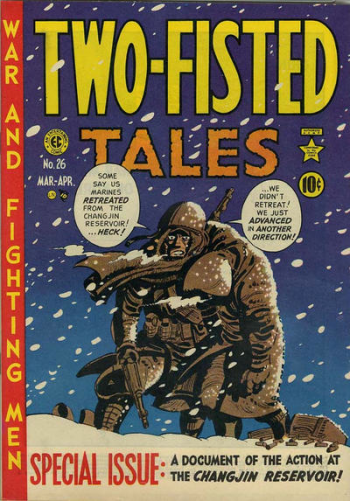

Like many rallying cries, Campbell’s piece is long on rhetoric but short on substance. His primary example as to the brilliance of the EC War line is the cover to Two-Fisted Tales #26.

“Some say us marines retreated from the Changjin Reservoir! …Heck!…we didn’t retreat! We just advanced in another direction!” – Harvey Kurtzman

“Let me fix the Kurtzman war comic in the reader’s mind before moving on. Here is the cover of Two-Fisted Tales #26, March 1952. There is a whole story in it and the way the story is told is quite sophisticated. A soldier in the middle of a historical action is already referring to it in the past tense. The first time I saw Kurtzman’s war comic art I wondered how on Earth he was able to get away with something so radical as that choppy cartooning, so far removed from what one would expect in war art…” – Eddie Campbell

Now Campbell gives my name quite a bit of play in his article. He mentions it again here as if I was denying Kurtzman’s skillful storytelling in certain stories done for the EC war line — as if no juice could possibly be pressed from mediocre fruit. I would ask interested readers to read the article he cites to see for themselves if I have denied Kurtzman’s talent for cartooning as Campbell’s hysterical pronouncements seem to suggest.

Readers not predisposed to give Campbell carte blanche might be slightly confused by the logic of his arguments. The second half of his article assails us with an example of a superior comic-ness which deserves praise, but his half-hearted readings of the EC war comics don’t match this aesthetic appeal and simply revert to typical descriptions of the narrative and the art—Kurtzman’s “choppy cartooning” and the questionable narrative genius of the cover illustration in question:

“…there is a whole story in it” with “a soldier in the middle of a historical action […] already referring to it in the past tense.”

The first question one should ask is why this is especially notable or the mark of a great talent for comics. Are the soldier’s words a prophetic utterance which lodges itself into the entire fabric of Kurtzman’s Changjin Reservoir issue, or is it a philosophical discursion on the paradoxical nature of time and fate?

For those not inclined to read the comic or use their brains, let me just say that the answer is “no” to both these possibilities My suggestions seem utterly ridiculous because the answer is plainly obvious to any reader who regards the cover as a whole. There can be little doubt that the illustration and narrative communicate the language of cover advertising and propaganda.

The disheveled fighting man carrying his wounded comrade; the brilliant brush work twisting and turning—melding the two into one single beast straggling across a snow swept battle field; defiantly disabusing all non-combatants and the foolish crowd of onlookers (journalists and naysayers) of the possibility of any lack of bravery or incompetence. This is not a place for cowards or laggards but one for heroes (misunderstood, at the bottom of the chain of command, injured, or dead), who are not fighting for any abstract concept but just to survive.

What Campbell’s statement suggest is a solitary interest in technicalities, and how this differentiates him from the fans who flocked to superhero conventions during comic’s early years, I’m not entirely sure. When it comes to the spiritual content of Kurtzman’s work, he seems quite deaf or purposefully blind.

Lodged within Campbell’s thin description are other questions —whether we should judge a piece of art as a whole or by its parts; and if we accept that art can achieve greatness purely on the basis of its narrative skill or artistry, is that artistry of a level that we can forgive almost everything else (McCay’s Little Nemo comes to mind immediately).

Kim Thompson latches on to this in the comments section and I quote:

“Complaining that a comic is no good because the story is no good is like complaining that water isn’t a good liquid because oxygen isn’t wet. Bravo, Mr. Campbell.” – Kim Thompson

Thompson’s metaphor is of course thoroughly imperfect since oxygen is frequently found in its “wet” state in our modern world but let’s see what he’s getting at here. In Thompson’s comment, comics are likened to water, which every elementary school kid is taught is composed of hydrogen and oxygen atoms. In other words, through the combination of art (hydrogen) and story (oxygen), a new, fastidious, and fabulous art form is created known as comics (water). This art form bears only a cursory relation to those things which constitute it and is neither art nor story but something entirely new which obeys no “laws” of aesthetics except those which are conjured up in the rectum of Eddie Campbell (and, maybe, his editor Dan Nadel).

Of course, this line of thought is irrelevant if one assumes that a cartoonist-critic is interested purely in the utilitarian aspects of the art in question. If one simply wants to emulate Kurtzman’s drawing line or his almost extradiegetic storytelling, the absolute quality of the art in question is extraneous.

If we mean to be “critics” interested in the formation (or reassertion) of a canon, then the absolute aesthetic appeal of a comic takes on more importance. This was certainly one of the motivations behind The Comics Journal‘s Top 100 comics list (where the EC line plays a prominent part) — a list mired in the concept that as the roots of comics reside in degradation and populism, they should conform to and be judged by those criteria only. As such, when The Comics Journal Top 100 comics list was produced, it was not so much an exercise in choosing comics of artistic merit but a process of choosing the best smelling shit — shit which, presumably, has no relevance or connection to the world at large.

Campbells’ other argument for the genius of the EC war comics comes at the close of his piece:

“If comics are any kind of art at all, it’s the art of ordinary people. With regard to Kurtzman’s war comics, don’t forget that the artists on those books were nearer to the real thing than you and I will ever be. Jack Davis and John Severin were stationed in the Pacific, Will Elder was at the liberation of Paris. Maybe we should pay attention to the details.”

In this, he trots out an age old argument in buttressing these comics — their authenticity. And who can doubt this? For participation in war and killing (voluntarily or involuntarily) is self-legitimizing — the only truth when it comes to battle. The entire fighting corpus is like a single amoeba with a single mind and a single all-encompassing viewpoint. And why even consider the enemy, the dead, the relatives of the dead, or those who oppose war? Can a cartooning genius ever be limited in his vision or politics? Can he ever be sentimental and derivative? Can a cartooning genius ever be wrong?

_____

The other points in Eddie Campbell’s article will be dealt with in the rest of the roundtable.

Your view seems to be that any war story that does not examine every single possible viewpoint from every single angle is not just propaganda, but crap.

If you apply that same criteria to literature, film or art, then almost everything produced is propaganda and crap.

Since that is obviously not the case, I think your indignant view of EC war comics is driven more by your politics than your critical objectivity.

I think the best way to judge Kurtzman’s EC war books is to examine them as a whole — not a cover here or story there. Overall, did he try to capture war as accurately as possible? Did he try to look at it from different angles — including those of both combatants? The answer to both is yes.

Russ, if you wanted to make that case in a post, I would love to print it. (I know you’re pressed for time…but hoped it wouldn’t hurt to ask.)

Interestingly, I think Eddie Campbell would actually disagree with you…or at least so it seems from the comment here and his further remarks under it. From what he says there, it sounds like he thinks that the EC war comics have a few good moments…and that that’s really all he expects from art.

So pretty much the opposite of your suggestion that you should look at the books as a whole. Campbell seems to be arguing that you *should not* look at the books as a whole, that looking at them as a whole is unfair and useless, and that the only fair or interesting way to talk about art is to look for moments of brilliance or excitement and ignore the rest, since negativity can’t lead you anywhere interesting.

Or at least…that’s the best I can make out as to what he’s saying. If someone else has a different read, I’d be interested to hear it. It certainly explains why his article lacks what I would consider a close engagement with the work he discusses; he seems to think that such close engagement is suspicious, and to be avoided.

Suat: ” It has been said that the purported ideals of that magazine never existed in the first place.”

Of course not. It’s been proven time and again. As for top 100 lists, or whatever, don’t forget this very site’s abomination. It’s a well established idea among the comics literati that comics are crap.

As for the “reality” of Harvey Kurtzman’s war if a bird that forgot the concept of a scarecrow is Eddie Campbell’s proof I rest my case.

Noah — If that’s what Campbell is saying, I have to wonder why.

As for an essay, that’s simply not in the cards right now. As it is, I’m trying to put together some of my thoughts about the demise of CBG/TBG.

You know that kid soldier doesn’t look dead to me, he looks like he’s taking a nap after shooting a million guys and holding the line? Maybe that’s because of the art I’ve been exposed to? In one of these comics maybe still always means dead?

That Marines-in-snow cover actually has a lot of guts to it. How often do you see depictions of defeat of “our boys” on a war comic cover? That’s my takeaway — the power comes from the tension between the defiant, self-deprecating, bitter words, and the visual starkness of defeat and exhaustion.

Although 30 years later, Kurtzman winced at the corn of “Retreat? Heck!”

I think Campbell’s probably right that the soldier is supposed to be dead. I don’t think he’s right that that works against the tweeness, or that it’s somehow deep. To me it seems like fairly standard and kind of cheap irony.

Isaac Rosenberg has a similar use of animals as a comment on warfare, which seems a lot more subtle and thoughtful. To me. No doubt Campbell would feel the comparison is invalid…but folks can decide for themselves. Here’s Rosenberg’s poem:

‘Break of Day in the Trenches’

The darkness crumbles away

It is the same old druid Time as ever,

Only a live thing leaps my hand,

A queer sardonic rat,

As I pull the parapet’s poppy

To stick behind my ear.

Droll rat, they would shoot you if they knew

Your cosmopolitan sympathies,

Now you have touched this English hand

You will do the same to a German

Soon, no doubt, if it be your pleasure

To cross the sleeping green between.

It seems you inwardly grin as you pass

Strong eyes, fine limbs, haughty athletes,

Less chanced than you for life,

Bonds to the whims of murder,

Sprawled in the bowels of the earth,

The torn fields of France.

What do you see in our eyes

At the shrieking iron and flame

Hurled through still heavens?

What quaver -what heart aghast?

Poppies whose roots are in men’s veins

Drop, and are ever dropping;

But mine in my ear is safe,

Just a little white with the dust.

Rosenberg is of course writing from personal experience…and I believe he died in WW I, so there isn’t a ton of poetry by him, sadly.

What bothers me the most in these discussions is that any hint of high standards in comics is deemed “literary.” As if visual artists were, quoting Marcel Duchamp quoting a popular adage of his time “stupid as a painter.” This is something that I can’t understand because the last time I checked literature didn’t have a higher status than painting.

There’s also the little problem of “the story is crap, but the drawings are great (or the cartooning is great or whatever…).” The story are the words and the images, if the story is crap guess what the images are…

I agree that it’s odd that the literary is a stand in for high art. Is EC Comics comparable to Picasso in terms of its take on war, for example? Comparable to the Vietnam war memorial? Are those unfair comparisons to make also? Is the objection to the use of literature, or is it actually to the act of comparison? They both seem to get garbled together….

Isn’t that a fairly traditional hierarchy, privileging the word over the image? At least, that’s what I remember reading in WJT Mitchell and others.

I think there can be a privileging of word over image…but I think also in comics there’s also a tendency in some quarters to privilege images over words. And is comparing a comic to a work of literature necessarily privileging word over image? After all, there are words in comics….

Yes, and words do not work as in the literature. Precisely because they are next to images.

By the way, Eddie will not argue you about the greatest poem of WWI. Maybe you should read again his piece, Noah.

Well, I read it several times. I didn’t say he’d argue about which was greatest; I said he’d argue that the poem shouldn’t be compared to the illustration. I’m pretty sure that’s the point of his essay; that comics shouldn’t be compared to literature.

The problem with saying that words do not work the same in comics as they do in literature is that you’re assuming that words work one way in all literature and one way in all comics. I think, on the contrary, that different artists use words in different ways, whether in comics or literature. Those differences (and similarities) seem more important to me than the particular form.

Though it’s quite possible that Eddie doesn’t think that any comparisons between any art are worthwhile, I guess. Or maybe he’s opposed to qualitative evaluation? It’s not entirely clear….

“you’re assuming that words work one way in all literature and one way in all comics”

Of course, because it’s the way it is. The image/text is not the same as the text at all.

About comparisons, I think -as I told you here before– there are relevant and irrelevant comparisons.

Ok, let’s compare Rosenberg’s poem with a rock song…. so who needs Elvis, or the Stones? Who needs the fucking ‘Gimme Shelter’? After all, is only one of the masterpieces of rock… but, you know, with those lyrics so obvious and unsubtle, how can we compare with Rosenberg’s poem about war? (of course we have to put aside how the Stones lyrics work in relation to music, voice, rhythm, an so on. Because words are words, etc.).

It maybe that Campbell is more a cartoonist the critic. I am not in his class or Kurtzman’s, in terms of cartooning. I am not in your class as a critic. I am not even as good a teacher as some, teaching comics. However, having been trained and working at all of the above, I find it difficult (when considering I am also a fan) to divorce myself from nostalgic, technical, narrative love for the medium and be objective. I am interested honorably in promoting the medium. Not tarring it apart. Selfishly I do wade into taking others works apart. But my own work is about as far from perfect as one gets in the art form. So I leave it to the pure critic to think and respond, as much as I can. However, I do ask the critic to keep in mind the challenges of cartoonist and teachers of cartoonist (we must critique as well) in terms of our speech on others work. That said, Campbell said it and you are simply responding in kind. We all want comics to improve, as paradoxically we want to celebrate and broaden the mediums appeal. These desires are both at once in conflict and harmony.

Pepo, I’m not exactly sure how you’re able to type with all the straw men squatting on your computer?

I’m not saying that you should ignore everything but the words. I’m saying that just because the mediums are different doesn’t mean you can’t compare them. And, again, I’d argue that individual artists and works should be looked at individually, rather than making blanket statements about mediums.

I like the Stones pretty well. Gimme Shelter is pretty mediocre overall, and definitely overplayed. The Stones in general are one of the most overrated bands in rock, I think. It’s their music that is kind of rote often, though; their lyrics are fine, if not revelatory or anything. Better than Dylan’s, anyway. (I mean, Sympathy for the Devil is really stupid, but usually they’re better than that.)

I have to admit though…I don’t really see the point of blustering about “masterpieces of rock.” What does that mean? Somebody says it’s great so therefore it must be great and no one can question it? That’s just silly. If you like it, that’s cool, and you can explain why if you’d like. But citing the zeitgeist as some sort of conversation ender just seems like you’re unwilling or unable to think for yourself.

I think the best “defense” of comics’ “greatest hits” is that making both words and images “great” and combining them in a “great” way is potentially harder to do than “just” making one great painting or one “great” poem. So…it’s not that we shouldn’t admit that there are some glaring weaknesses in Kurtzman’s stories…but that what’s “great” about them potentially outweighs those weaknesses…and we have to cut comics some slack given the extreme difficulty of getting all of those aspects to be “great.”

I’m not sure it’s a valid argument, really, but it makes more sense than saying the great comicsness of this comic simply can’t be seen/judged from a “literary” perspective.

There IS a story in these comics and if that story is cliched, melodramatic, corny, etc…then it’s got some problems that can’t be dismissed simply by saying “that’s comics!”–After all, many comics, or some anyway, are not cliched, melodramatic, corny, etc…

Pepo’s discussion of song lyrics is an interesting comparison, really. I think Gimme Shelter is one of the Stones’ 2-3 best songs…but I wouldn’t think of reading the lyrics as separate from their delivery and accompaniment.

But…even with that comparison, I think the key is, when listening to the song, it doesn’t feel trite, corny, awkward, leaden…etc. Maybe, when read, it would, but we don’t (or shouldn’t) read song lyrics…. In the case of Kurtzman, we are talking about finding the story corny, cliched, etc. as we read it. To do so is not to separate it from its millieu, but to find it wanting within it.

And Russ talks about what Kurtzman “tries” to do in his war comics. Shouldn’t they be judged on what he actually accomplishes, not on what he attempts.

BTW, I’ve read only a few of the Kurtzman war comics, and found some of them to be enjoyable…I do see a number of the problems Suat identifies, however. Eddie Campbell’s defense seems sadly familiar… It kind of assumes Suat doesn’t know comics or hasn’t read any…or doesn’t understand them and therefore reads them independently of their pictures, purely for words and plot. This is transparently false. Campbell likes the comics and Suat doesn’t–ok–but Campbell doesn’t actually engage with Suat’s critiques, so it hardly works as a critique of Suat’s critique. Instead, it’s a simple assertion that the Kurtzman war comics are good comics qua comics, with little evidence brought to bear to support that claim.

I’ll agree that Shelter, like Sympathy, is so overplayed that it’s hard to judge it at all at this stage…but Sympathy, though pretty stupid lyrically (to me, enjoyably–perhaps intentionally?– so), is a great song.

“Campbell likes the comics and Suat doesn’t–”

I don’t think Campbell actually says he likes the comic… he just seems to be saying there’s some “neat stuff” to be found there. He likes the panel with the bird…

The problem is that a work of art is a work of art is a work of art (and I’m including literature here). Comics exceptionalism makes no sense.

I really hate Sympathy for the Devil. The gimmicky addition of instruments; the stupid self-romanticization as evil hero…it’s such a pompous, derivative, bloated piece of crap. The Stones’ descent into self-parody is painfully foreshadowed.

Eric — Your point about analyzing what Kurtzman actually accomplished rather than what he tried to accomplish is valid, but I think in Kurtzman’s case, they are actually one and the same.

Kurtzman tried to change the way war comics were created — and succeeded. And while he had various editorial restrictions imposed on him that later creators would not, he still managed to create war comics that were, at the time, light years ahead of the competition.

I find the historically revisionistic attitude of some today who thumb their nose at his groundbreaking work shortsighted. Kurtzman pioneered the modern-day war comic, and while some may find the stories “quaint,” “jingoistic” or otherwise flawed, the fact is, when they were published, the stories and art were cutting edge.

“gimmicky addition of instruments”–I have no idea why this is supposedly gimmicky…

and the self-mythologization as evil hero is, at least partially, a joke– and one worth a chuckle the first couple hundred times. Also…like superhero comics, bloated self-mythologization can work quite well, if leavened with some irony, in rock music. Where would Bo Diddley be without it…and I love me some Bo Diddley.

Anyway…the Stones discussion is pretty off-topic so I’ll stop.

Bo Diddley isn’t ironic; he’s enthusiastic and boisterous, which is fun. The Stones aren’t ironic either; they think the Devil is cool, and they like being the devil and singing lines about the Kennedys which are really stupid.

And it’s gimmicky because it’s a gimmick; it’s supposed to be clever and tricky. And if it were a good gimmick it would be. But it’s rote and idiotic.

Russ…you’re basically saying that Kurtzman’s comics are of historical interest. Which is fine…but that isn’t exactly the same as saying that they should be held up as some of the best work in comics, it seems to me.

I seriously doubt they literally thought the devil was cool… It’s all part of the pose/marketing of the Stones as bad boys, etc…which is all part of the rock n’ roll tradition image…Just like I doubt Bo Diddley really thought that much of himself that he should have a song about how awesome Bo Diddley was (at least one!) on every album. Look at the cover of “Black Gladiator” for instance. It’s a joke. The Stones are joking, to some degree, too… And the instrumenting and hoo-hooing on Sympathy is actually quite clever. If it is rote, who were all the bands/singers that beat them to it?

I said I would stop…but couldn’t. I will try again.

Noah — Even work of by the best artists can lose its impact and become dated. Look at Warhol. But there’s no denying that he had a big impact on the medium and his contemporaries. Ditto for Kurtzman.

Sympathy is an adaptation of The. Master & Margarita. That doesn’t make it smart, but it’s missing from the discussion. Anyway, the Stones are factually the greatest rock band ever.

Joking isn’t exactly the same as being ironic, or undercutting. Bo Diddley’s persona is certainly a joke…but that doesn’t mean he doesn’t think he’s great (and he is!) And just because the Stones thought it was funny to be the devil, that doesn’t mean they didn’t think it was also cool.

And the additional tracks just are so eager to rear up and say “I’m clever!” The whole thing is so smarmy and self-impressed. Barf.

Russ, I don’t think Warhol’s dated at all. He’s still incredibly relevant both to art and to the culture at large…and I find his work still provocative and funny and sublime — and not as a historical “this was important once”, but as something that still speaks to me, the way any art I like speaks to me. The giant multi-colored Mao heads, turning this giant Communist monster icon into repeated images which is advertising which is also queer — it’s the joy and goofiness and the stupidity and the threat and the release of modernity in one enormous garish package. That’s what I want from my art, damn it — whatever era it happens to be from.

If you think Kurtzman is great art on his own terms, that’s fine — but you haven’t made a case for it. You’re still saying, “of historical interest.” And that’s not the same as saying that it’s great art.

Jesus, Suat, don’t hold back.

If nothing else, this whole “exchange” has thrown up some funny disses on either side, and will hopefully keep doing so. I lol’ed at the “for those not inclined […]” bit, and I thought Campbell’s Parnassus line was funny.

We’ll have to agree to disagree about Warhol.

The problem with assigning anything but historical impact to any artist is there are no objective standards for assigning greatness to any art — something I pointed out in my Ditko essay.

And if you think I’m wrong, then tell me what the standards of greatness are and I’ll tell you if I think Kurtzman meets the criteria.

Huh, I’d never heard of Master & Margarita. I’ve always loved Sympathy for the Devil, but that Kennedys line does make me cringe (handsome billionaire politicians who slept with Marilyn Monroe = Jesus Christ). To beat the Stones discussion to death and bring it back to comics, I once had a letter exchange with Dave Sim where he singled out that line as brilliant (see http://tinyurl.com/asxmg4b).

Of course there aren’t objective standards. But you can talk about what you’re looking for in art at this particular moment. I think that’s what Suat is asking for. Do Kurtzman’s war stories provide a complicated perspective on war, incorporating different perspectives. Or are they essentially jingoistic propaganda? Suat suggests that they veer closer to the later, and that he’s not able to see them as great art for that reason.

I mean…why do you like them? Is it the drawing technique? Is it because they’re pro-military? Or something else?

Charles, the Stones aren’t even in the top 20 greatest rock bands ever. Maybe top 100.

And Dave Sim…yeesh.

Master and Margarita is a great book…Big inspiration for Satanic Verses, which then refers back to Sympathy as well.

I think Campbell’s essay and Suat’s original piece both have their good points and flaws. Campbell’s defense of art with a seriously crappy side, like Casablanca, opera, and Billie Holliday’s rendition of mediocre songs, was impressive to me. But I don’t see what he was getting at with the “The EC guys were WWII vets and we aren’t” argument–I mean, Kurt Vonnegut, Joseph Heller, and Norman Mailer probably wouldn’t have liked the EC war comics any more than Suat does. I though Suat’s reference to Anne Frank was the best part of his piece–smart, sensitive kid trying to seriously express her thoughts and feelings > some talented guys trying to entertain teenagers.

You only need 2 rock bands: the Stones & Velvet Underground. The rest is perfunctory, Noah.

Jack: Noah will deal with the Billie Holliday/Batroc part of Campbell’s essay later on this week. So stay tuned…

But I don’t see what he was getting at with the “The EC guys were WWII vets and we aren’t” argument

Eddie’s claiming value on an authenticity basis, but I think privileging artists who are combat veterans over those who are not is a crock when it comes to war material. For my money, the best Hollywood war film of the 1950s is Paths of Glory, and the trench combat scenes are among the most impressive parts. But Stanley Kubrick, who directed it, had never served in the military, much less seen actual combat.

People who think Kurtzman was daring for his time ought to consider the history of Paths of Glory after it was released. The anti-war message and harsh criticism of top military officers and their motives did not sit well with many powerful people. It was banned in Spain for nearly 30 years. The French government never went quite that far, but they leaned on the production studio not to release it over there. You couldn’t see it in France until the 1970s. It ran into trouble with the German government, too, as I recall. Kubrick took many more chances than Kurtzman, and he did so with a lot more money on the line.

I like VU a lot. But if I had to go to a desert island, I’d trade them for Steely Dan in a heartbeat.

And my piece will be up tomorrow I think.

Yeah…and again I mention Remarque, who was exiled for his war writing, had his books burned in his native land, and then had his sister murdered. And of course there are people like Victor Jara, or less dramatically Pete Seeger, who experienced real persecution for their art.

Not that being persecuted means you’re a great artist or anything. I think All Quiet on the Western Front is seriously flawed; I’ve got major reservations about Pet Seeger’s music, and I’ve never heard Victor Jara’s. But if you’re going to talk about courage, it seems worth pointing out that there are actually artists who have been really courageous and suffered for it, and that you need to be…well, let’s be kind and say a little myopic to seriously put Kurtzman in that company.

Haha, back to Suat’s essay …

Robert, I’m probably closer to Suat’s side and Kubrick is my favorite, but in fairness to Kurtzman, PoG is critical of the French coming from an American.

The original Campbell’s piece is perplexing. Or am I the only one seeing confusion between ‘literary quality’ and complexity/sophistication of the plot there? As if a ‘literary’ element of a work of art equals the retelling of its plot. This… is not how literature works. True, you can’t explain the value of Casablanca by its plot, but it’s not like you can do it for Anna Karenina either.

Ah, Master and Margarita. Good book, wildly overpraised though (popularity-wise it’s pretty much Twilight for the generation before mine).

“I’m pretty sure that’s the point of his essay; that comics shouldn’t be compared to literature.”

In a nutshell I think he feels the particular literary comparisons Suat made were over the top and inappropriate. Even so, Campbell then brings up comparisons to Billie Holiday and opera vis a vis comics which don’t make complete sense.

Part of all this I think is due to the traditional artist / critic divide. There’s always going to be that unresolved tension between the two.

“Russ…you’re basically saying that Kurtzman’s comics are of historical interest.”

That’s what Groth was saying in his essay. But I guess that’s to be expected from the publisher.

“It kind of assumes Suat doesn’t know comics or hasn’t read any”

Yes, that’s a standard reply you get many times when critiquing the sacred cows. I got the same response over there one time after zinging Gilbert Hernandez.

In his post Campbell displays a Ditko Spider-Man page he first came across when he was nine. I wonder how much of his appreciation for ECs comes from nostalgia. If he were an adult and coming across ECs for the first time, would he have felt the same way about them?

“In his post Campbell displays a Kirby Captain America page…”

“The problem with assigning anything but historical impact to any artist is there are no objective standards for assigning greatness to any art…”

But cultures do tend to come to an agreement about a central core of essential artists. Ingres, Rembrandt, Picasso, Mozart, Dickens, Brahms, etc. etc. In any “canonical” list of course there’s going to be disagreements about certain particular artists and/or their works. But certain artists do tend to get mentioned over and over again. The problem with Campbell’s Billie Holiday example is that her work is universally admired. It’s an important part of American culture and appreciated as such by many people who don’t listen to Jazz. EC Comics by contrast are important only to a tiny subset of the population and will always remain so. There are perfectly valid reasons for this and it’s not due to snobbery.

How could Campbell’s appreciation for EC come from nostalgia? Doesn’t anybody here have a sense of chronology?

Presumably he first came across them as a kid? Just like with the 60s Marvels he writes about?

“Presumably he first came across them as a kid?”

Hey, If you don’t know, just make it up, why don’t ya!

AB is right, most of us never saw this stuff till Russ Cochran started reprinting it in 1978, by which time I was 23.

I was assuming, since you brought up how the 60’s Marvels affected you. Thanks for replying.

———————-

Ng Suat Tong says:

Kim Thompson latches on to this in the comments section and I quote:

“Complaining that a comic is no good because the story is no good is like complaining that water isn’t a good liquid because oxygen isn’t wet. Bravo, Mr. Campbell.” – Kim Thompson

Thompson’s metaphor is of course thoroughly imperfect since oxygen is frequently found in its “wet” state in our modern world but let’s see what he’s getting at here. In Thompson’s comment, comics are likened to water, which every elementary school kid is taught is composed of hydrogen and oxygen atoms.

————————-

Nothing “of course” about it. Thompson simply said “oxygen”; not H2O. Just as if someone mentions “sugar,” they’re not necessarily referring to cakes, even if cakes contain sugar.

————————–

…when The Comics Journal Top 100 comics list was produced, it was not so much an exercise in choosing comics of artistic merit but a process of choosing the best smelling shit — shit which, presumably, has no relevance or connection to the world at large.

————————–

What, “shit…has no relevance or connection to the world at large”? I look at the world “at large” and a huge proportion of what is man-made (in politics, religion, philosophy, the media) is “shit.”

Compared to which, EC comics are towering examples of enlightenment and sophistication.

—————————-

Domingos Isabelinho says:

It’s a well established idea among the comics literati that comics are crap.

—————————–

If so, why one one bother to become a “literati” of the art form? Masochism?

——————————-

…two elderly women are at a Catskill mountain resort, and one of ‘em says, “Boy, the food at this place is really terrible.” The other one says, “Yeah, I know; and such small portions!”

-Woody Allen

——————————-

——————————-

Domingos Isabelinho says:

What bothers me the most in these discussions is that any hint of high standards in comics is deemed “literary.”

———————————

If there were not even a “hint of high standards in comics,” then would not Rob Liefeld or any piece of bat-drek have made it as easily into those sneered-at Top 100 lists as the Hernandezes, Kurtzman, Herriman? Why, surely their vastly greater numbers would’ve meant that superhero comics would overwhelmingly dominate.

It’s not “high standards” that are rejected, it’s absurdities that are the equivalent of criticizing a pianist by the standards of an Olympic athlete.

——————————

As if visual artists were, quoting Marcel Duchamp quoting a popular adage of his time “stupid as a painter.” This is something that I can’t understand because the last time I checked literature didn’t have a higher status than painting.

——————————-

Isn’t criticizing a comics story by the standards of “painting” equally as absurd?

———————————

There’s also the little problem of “the story is crap, but the drawings are great (or the cartooning is great or whatever…).” The story are the words and the images, if the story is crap guess what the images are…

———————————–

If Mr. A was a critic, this is the subtlety one could expect. “Most of the so-called ‘great operas’ are crap, because their stories are idiotic!”

As I said over at TCJ.com:

————————————

By all means, those factors are important. Meriting critical interest, and hosannas or razzberries where due.

However, the overall reaction here is against the attitude which dismisses the totality of the work, condemns the gestalt…

…because some parts in isolation may not be great.

From Dave Berg: http://i1123.photobucket.com/albums/l542/Mike_59_Hunter/DaveBergDentist1_zpsc341be5a.jpg

———————————–

———————————–

Pepo Pérez says:

The image/text [in comics] is not the same as the text [in literature] at all.

———————————–

Indeed; just like water shouldn’t be criticized for not acting like a gas, even though it contains gases.

———————————–

Ben Cohen says:

It maybe that Campbell is more a cartoonist the critic.

————————————

Yes; his critical arguments are not as linear and carefully nailed-down as I’d prefer. I can well understand Jaelinque’s finding his original piece “perplexing.” Still, he’s very intelligent (as well as a truly great talent), and he can make some compelling, even if to me startlingly counterintuitive, arguments. Such as, notably, in counterpoint to Scott McCloud’s structurally-based definition of comics, arguing that it’s certain shared tropes and characteristics that better define comics.

————————————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

…I’m not saying that you should ignore everything but the words. I’m saying that just because the mediums are different doesn’t mean you can’t compare them.

—————————————

It certainly is useful and thought-provoking to “compare.” However, what we have here is nothing so neutral-sounding; it’s blasting one because it’s not like the other. From that TCJ post:

Re the damning of a work because it may not have certain admirable qualities, am reminded of a friend of critic John Simon, who upon leaving a performance of “Macbeth,” would loudly announce, “It’s good, but it’s not ‘Oklahoma!'” Then, exiting a performance of the famed musical, would call out, “It’s good, but it’s not ‘Macbeth’!”

Does it make sense to criticize a gloomy drama by the exact same standards one would a rousing musical? To expect, say, “Where the Wild Things Are” — about as perfect a work as one could ask for — to have the character complexity, sweeping portrayal of a society, range of humanity, of a “War and Peace”?

Then, to dismiss Sendak as a hack, or mediocrity, because he can’t do what Tolstoy did?

———————————-

And, again, I’d argue that individual artists and works should be looked at individually, rather than making blanket statements about mediums.

———————————–

Why should it be either one or the other? Isn’t it likewise useful and thought-provoking to study the factors which make an art form effective/limited within its own parameters?

———————————–

Russ…you’re basically saying that Kurtzman’s comics are of historical interest. Which is fine…but that isn’t exactly the same as saying that they should be held up as some of the best work in comics, it seems to me.

————————————-

Why should it be either one or the other? Can’t some art appear outdated, its once-groundbreaking approaches now tiresomely overfamiliar through imitation, certain qualities laughable, even vile… (i.e., Griffith’s “Birth of a Nation”; Eisenstein’s “Potemkin”)

…and still remain “great”?

Mike — “Birth of a Nation” is a great example. Despite its racism and other flaws, and despite the fact it is primative by today’s film standards, its impact on the cinema when it was released was undeniably enormous. That’s why it is a “must watch” for any serious film student — just like Kurtzman’s war comics are a must-read for any serious student of comics.

Mike, the thing is, Eddie says Suat is complaining that comics aren’t literature…but that’s not what Suat actually did in his essay. Similarly, while something can both be of historical interest and great, arguing that one is the first is not the same as the second. If you want to argue the second, you need to argue the second. Citing the first doesn’t help you get there.

Where the Wild Things Are is more a poem than a novel. I agree it’s pretty perfect — which is certainly in part because the language is beautiful. I actually think it’s better than War and Peace, which gets bogged down in Tolstoy’s historical theories, which are mostly fairly stupid. The romance at the center of it is irritating too. (Anna Karenina, on the other hand….)

“Isn’t criticizing a comics story by the standards of “painting” equally as absurd?”

You’re missing the point. It’s not “literature” or “painting,” but rigor. That’s the bottom line. So I guess one is supposed to divorce the endless blocks of text, the cheap surprise endings, the clumsy dialogue and still call it “art.” The last time I checked, comics were both word and image working together. Not one or the other.

Noah — I think you’re being unrealistic by trying to separate historical interest from greatness.

“Birth of a Nation” was great when it was released because it was groundbreaking and spectacular to contemporary audiences.

If it was released today, if even taken seriously at all, it would be almost universally excoriated and shunned.

In short, its greatness was directly related to its historical time frame — just like Kurtzman’s war comics.

One of the subjective measuring sticks often cited for great art is timelessness. And while it’s true that some of Kurtzman’s war comics are dated, some of his stories (and some of the art), are still as powerful today as they were when they were first published.

Russ: “Birth of a Nation” was great when it was released because it was groundbreaking and spectacular to contemporary audiences.

Does this mean we should also unabashedly celebrate Triumph of the Will because of its historical context? You know, Nazis and early 1930s. You just had to be there to understand.

Btw, lots of people seemed to have hated Birth of a Nation when it was first released. I think Birth of a Nation is a pretty terrible movie all in all. But it is an American “classic”…

Mike: “If so, why one one bother to become a “literati” of the art form? Masochism?”

It varies I suppose, but I guess that it is a cocktail of populism, formalism and nostalgia.

As for your other comments either you didn’t understand what I was saying (my fault, no doubt) or see Steven’s answer above…

A few of Campbell’s later comments, further down the thread-

1:

“That’s right. I don’t necessarily disagree with him, though its not something I would be bothered to argue about as I can’t see what could be gained by it (there is even less to be gained in the Lee-Kirby argument). I was addressing the problem of the way comics are written about, and the criteria used to assess them”

2: “Comics criticism is too concerned with the destination when it could be enjoying the journey.”

Yeah…I haven’t seen Birth of a Nation, Russ, and don’t really see any reason to; it sounds dreadful and…well, of basically historical interest.

I wasn’t that into Citizen Kane either. Again, I know there are formal innovations, but the narrative seemed tedious and the cheap psychologizing reversal at the end idiotic. Touch of Evil is great though.

Again, it’s fine if you want to make the case for Kurtzman’s work as still affecting. It’s even fine to argue that “of historical interest” is really all that we should measure greatness by. I disagree; if something was historically innovative, that can be interesting to know about, but it isn’t what I look for in art, or what I consider great art. I want art to teach me something, or make me cry or laugh or feel a sense of the sublime; to engage my head and my heart. “It was good for its time,” or “it was good for its time for being a comic book” doesn’t get me there or interest me that much.

“and the cheap psychologizing reversal at the end idiotic.”

Welles himself in time was in full agreement with that assessment. No, it’s not a deep picture. The best one can get out of it is the enjoyment of a talented young buck clearly having the time of his life. Anyway, my favorites of his are “Lady from Shanghai” and most of all Chimes at Midnight.

“Birth of a Nation” is not simply some historical footnote to film historians, it broke new cinematic ground. Through it, Griffith literally laid all of the groundwork for the modern feature film. He also was the first to embrace many of the elements filmmakers today take for granted — close-ups, fades, tracking shots, long shots, etc.

Ng — don’t go down a rathole here by bringing up the Nazis. The Nazis pioneered modern-day rocketry, and while it needed by “celebrated” it must be acknowledged.

In Kurtzman’s case, I think his pioneering work should be both celebrated and acknowledged.

That’ “need not be celebrated, but it should be acknowledged”

“In Kurtzman’s case, I think his pioneering work should be both celebrated and acknowledged.”

Nobody’s not acknowledging it though. I don’t have any problem saying that Griffith or Kurtzman were historically important, and neither does anyone else in the discussion, as far as I can tell.

But claiming that their work should be celebrated is a different thing. And to make that argument, you need to make that argument. Referencing their historical importance is a red herring. Everybody agrees on the historical importance. What’s at issue is their status as worthwhile art.

Yup and saying that these are worthwhile comics as if comics are something different from art (or no art at all I suppose) doesn’t do it either.

My view of The Birth of a Nation:

http://polculture.blogspot.com/2012/01/movie-review-birth-of-nation.html

Russ is making it sound like it’s in the same class as The Jazz Singer, and that’s just not the case.

While we’re at it, my view of Battleship Potemkin:

http://polculture.blogspot.com/2012/04/movie-review-battleship-potemkin.html

I recommend Mike sit down with it again, and this time make sure he’s watching a quality print.

And while I’m picking on Mike, there’s this statement:

Re the damning of a work because it may not have certain admirable qualities, am reminded of a friend of critic John Simon, who upon leaving a performance of “Macbeth,” would loudly announce, “It’s good, but it’s not ‘Oklahoma!’” Then, exiting a performance of the famed musical, would call out, “It’s good, but it’s not ‘Macbeth’!”

I think I’d be interested in a discussion of Where the Wild Things Are vs. War and Peace. It’s such an odd compare-and-contrast pairing that I’d be curious what the writer was up to. But let me take the opportunity to defend Suat’s comparison of Aristophanes and Kurtzman. It’s actually quite apt. The dominant mode for both was satirical farce. They both enjoyed parodying other artists, and they both had a ribald sense of humor. There are some today who find Aristophanes just as off-puttingly vulgar as they might find Kurtzman. New Yorker film critic David Denby, perhaps the epitome of middlebrowism among contemporary reviewers, once called Aristophanes “merely crude,” and wrote that his material “hadn’t worked for me at all.” I personally wouldn’t have made the comparison, mainly because I don’t think anyone reading an article on EC would be expected to know who Aristophanes is, but he and Kurtzman are definitely cut from the same cloth.

I did think Suat’s original piece was rather pompous. “We’ve been mucking about in the sandbox for long enough,” always bugged me–isn’t all criticism ultimately mucking around in a sandbox? If the TCJ Top 100 List has any value, I think it’s along the lines of some nerds offering insights about and/or calling attention to their favorite works, provoking discussion, encouraging cartoonists, and giving Cerebus fans something to bitch about. In contrast, Suat seems to think the list was or should have been an important historical moment of cultural cannonization on the part of serious intellectuals. Critics tend to overrate the importance of criticism, in my opinion.

While I’m being a jerk, I thought I’d add that since I started reading the Comics Journal Message Board around 1998, I haven’t read one comment by Kim Thompson that I agreed with even slightly. Whether Kim is defending For Better or For Worse, complaining about Ralph Nader, or coming up with some weird-ass analogy between criticing comics writing and criticizing water’s oxygen content, I always think he’s 100% wrong. The weird thing is that I absolutely love Fantagraphics and TCJ and almost always agree with Gary Groth. Go figure.

Finally, I like Kurtzman’s artwork a lot, and the fact that he created MAD and inspired most of my favorite cartoonists puts me forever in his debt, but I have to agree that the old EC dramatic writing could be annoying. The Jack Davis panel in Campbell’s essay is a good example–great art by one of the all-time masters, but some lame narration. “Dawn in Korea! The sun is rising on a little bird!” A little subtlety would have gone a long way in those comics. I’ll admit that I haven’t read many of the war books, though.

RSM wrote — “Russ is making it sound like it’s in the same class as The Jazz Singer”

No, I didn’t. The Jazz singer was arbitrarily a film historic significance. Almost any film could have been plugged into its place by the studio to be the first full-length “synchronized sound” picture and it would have probably been a technological sensation. But the fact it was a musical really put “the talkies” in the stratosphere almost overnight.

“Birth of a Nation,” however, broke all sorts of new cinematic ground, which I pointed out in my post thusly, “Griffith literally laid all of the groundwork for the modern feature film. He also was the first to embrace many of the elements filmmakers today take for granted — close-ups, fades, tracking shots, long shots, etc.”

In that regards, “Nation” was definitely a much more sophisticated film that “Jazz Singer” — even though “Singer” was filmed a dozen years later. Ditto for Griffith’s masterpiece, “Intolerance.”

I´ll say what I said over Campbell´s post but I´ll be more vernacular here: he falls in cheap rethorics instead of articulating a real argument. Wether he talks about image/text, text/image, image with no text, the whole, the part, the popular or whatever in the end he is in the same shithole since he, as the “literaries” he refers to, seem to think that comics only exist to tell stories. (Not to imply that I don´t think that comics shouldn´t tell stories or that criticism about it may not be of value, but his post is pretentious shit as few)

Jaelinque wrote: “The original Campbell’s piece is perplexing. Or am I the only one seeing confusion between ‘literary quality’ and complexity/sophistication of the plot there? As if a ‘literary’ element of a work of art equals the retelling of its plot. This… is not how literature works. True, you can’t explain the value of Casablanca by its plot, but it’s not like you can do it for Anna Karenina either.”

You are very right. A couple of years back I was asked to write a blurb for Nicki Greenberg’s comics adaptation of Shakespeare’s Hamlet. I wrote succinctly about the ways in which Nicki’s cartoons added to, enhanced and decorated the original, to the best of my ability. When I later saw a dummy of the book I was surprised to see that my blurb had been replaced by a plot summary. I got on the phone and argued the matter, saying you wouldn’t put a plot summary on the back of Shakespeare’s Shakespeare, why are you doing it on the back of Greenberg’s? In the end my original blurb was reinstated in an edited form.

A quick check on the internet shows that they are back to using the plot summary:

“Denmark is in turmoil. The palace is seething with treachery, suspicion and intrigue. On a mission to avenge his father’s murder, Prince Hamlet tries to claw free of the moral decay all around him. But in the ever-deepening nest of plots, of plays within plays, nothing is what it seems. Doubt and betrayal torment the Prince until he is propelled into a spiral of unstoppable violence.”

source:

http://www.thenile.com.au/books/Nicki-Greenberg/Shakespeares-Hamlet/9781741756425/?gclid=CNr7iuDHsrUCFUE3pgoddiAAew

You are right to say this is not how literature should work. But a book publisher seems to think it’s how comics should work. Is this a depressing sign of the times, or a depressing sign of the relative esteem in which comics are held?

In that online ad for the book, there is little about it being Nicki Greenberg’s graphic rendition of the play. It is presented as though it was, not even just the words, but just the plot, which is less than everything. Anybody with half a brain can get the plot in an instant google. The space allotted to that summary is surely wasted. It should have been a clever lure, if not mine then somebody else’s. Or am I overestimating ordinary people?

Before anybody goes making stuff up again, my original blurb went like this (from the back of the book, as finally published):

“The finest thing about Shakespearean drama is that the work can be restaged for every generation and in so many different ways. In Nicki Greenberg’s version, Hamlet is played by an inkblot with a crowquill in his scabbard. The settings sparkle; the interior of the castle has a decor of suspended clock parts, curious only until we realise that “time is out of joint.” Polonius pops in and out of a sheet of paper as he reads Hamlet’s letter to Ophelia, and Ophelia walks us physically through the botanicals so we don’t need opera glasses to follow the symbolism of the flowers. Greenberg’s adaptation of The Great Gatsby was entirely in monochrome and it’s exciting this time around to see her unpack a palette of riotous colour.”

I didn’t think of it at the time, but this is a precise example of my original argument. Book publisher doesn’t quite get comics and wants to replace apt description of the work, from an artist and former self-publisher of comics, with a potted plot summary. And we’re talking about Hamlet.

Russ–

Sorry for the misunderstanding.

——————–

steven samuels says:

[Mike sez] “Isn’t criticizing a comics story by the standards of “painting” equally as absurd?”

You’re missing the point. It’s not “literature” or “painting,” but rigor. That’s the bottom line.

———————-

How could I be “missing the point” that it’s lack of “rigor” being criticized, when no one has brought up “rigor” as a standard for criticism?

————————

So I guess one is supposed to divorce the endless blocks of text, the cheap surprise endings, the clumsy dialogue and still call it “art.”

————————-

If the “Fine Arts” world would can seriously call some canned Artist’s Shit, or a light switch being flipped on and off, or — on a wittier level — a urinal mounted on a gallery wall, “art,” I don’t see why not.

Needless to say, that a work fully qualifies as “art” doesn’t mean that it ascends the heights. There’s room for quite a range in quality.

————————–

The last time I checked, comics were both word and image working together. Not one or the other.

—————————

Oh, so are the captions in an EC horror comic on one side of the room, the images in the other? They may not be as nicely integrated as in Kurtzman’s own EC comics, there’s plenty of redundancy (which actually creates its own odd aesthetic effect), but they still do work together.

—————————–

Ng Suat Tong says:

Russ: “Birth of a Nation” was great when it was released because it was groundbreaking and spectacular to contemporary audiences.

Does this mean we should also unabashedly celebrate Triumph of the Will because of its historical context? You know, Nazis and early 1930s. You just had to be there to understand.

——————————

I like that “unabashedly”; talk about putting your thumb on the scale!

When Russ says re the Griffith film, “its greatness was directly related to its historical time frame,” he is referring to the other work that was being done in cinema at that time.

Reifenstahl’s brilliant “Triumph of the Will” was not even remotely as influential, or precedent-setting, in its era; movies had become far more sophisticated by then. And her grandiose, operatic approach does not “translate” as well to other films. Yet it remains admired by cinephiles.

—————————–

Btw, lots of people seemed to have hated Birth of a Nation when it was first released.

——————————-

Solely because of its Klan-glorifying, racism-pushing message; not for its artistic failings. Or are you arguing that ideological odiousness = aesthetic crappiness?

——————————-

I think Birth of a Nation is a pretty terrible movie all in all. But it is an American “classic”…

——————————-

It’s significantly flawed; unsophisticated in technique compared to much of what came after; yet brilliant in many ways.

——————————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

I wasn’t that into Citizen Kane either. Again, I know there are formal innovations, but the narrative seemed tedious and the cheap psychologizing reversal at the end idiotic.

———————————

(No comment)

Oh, hell, I can’t resist. Could there be any better example of the attitude of those unable to appreciate, er, “be into” what has been rightly acclaimed as outstanding works of art by the majority of the world’s critics of that art form, because of focusing on a few flaws?

And, “I know there are formal innovations”…sheesh!

———————————-

Robert Stanley Martin says:

My view of The Birth of a Nation:

http://polculture.blogspot.com/2012/01/movie-review-birth-of-nation.html

———————————–

That’s not only beautifully written, but a tidy summation of its flaws and virtues.

————————————

While we’re at it, my view of Battleship Potemkin:

http://polculture.blogspot.com/2012/04/movie-review-battleship-potemkin.html

I recommend Mike sit down with it again, and this time make sure he’s watching a quality print.

—————————————

(??) I own a copy. My arguments with the film’s flaws (“Can’t some art appear outdated, its once-groundbreaking approaches now tiresomely overfamiliar through imitation, certain qualities laughable, even vile… (i.e., Griffith’s ‘Birth of a Nation’; Eisenstein’s ‘Potemkin’)…and still remain ‘great’ “) remain in place, regardless of how pristine the print might be.

The ‘laughable” are items such as the overwrought emotionalism in the famous “Odessa Steps sequence” (much is made of a baby carriage, complete with rug rat, being in Perils of Pauline melodramatic-type danger), which is still great.

The “vile” is Eisenstein’s propagandistic lying, inventions and distortions of history, done at the behest and in the service of of Stalin, one of history’s most monstrous tyrants and greatest mass murderers.

I don’t see why your description is more accurate than the editor’s. I would prefer yours, of cours (as you say, it’s Hamlet, who needs a plot summary?), but doesn’t the blurb describe what happens in the book?

The problem with essentialism is that 1) it’s arbitrary, 2) it’s either too specific or too broad.

On the other hand the plot isn’t literary only. I can imagine a plot description of a Masereel cycle (to avoid the “graphic novel” can of worms). Is that literature also? I can imagine some folks saying, yes it is, but I can imagine other people saying, no it isn’t, and I don’t see any reason for one group to be right and the other one wrong. personally I call it comics in the extended field being the plot part of comics as it can also be part of a (pictureless, panelless) novel, but that’s just me.

It’s as obvious as a plot summary of Hamlet, but, the above was an answer to Eddie.

Mike: “If the “Fine Arts” world would can seriously call some canned Artist’s Shit, or a light switch being flipped on and off, or — on a wittier level — a urinal mounted on a gallery wall, “art,” I don’t see why not.”

If you want to criticize (Dadaist, neo or not) Conceptual art you better get your decoding protocols straight. You can’t “read” a conceptual work of art as if you were reading a painting or a sculpture. The object is of as much aesthetic interest as words in a novel. They’re there just to convey the idea. In Duchamp’s case he repeatedly insisted on the neutral aesthetic qualities of his ready-made choices. The fact that this first ready-made is a urinal (signed R. Mutt to all of us comics nerds’ enjoyment) adds a little paradox to the mix, of course, because a urinal is a scatologically charged object. Duchamp was a fine joker if I ever saw one (another capability that comic nerds enjoy, I guess…).

No one mentioned “rigor,” but no one mentioned evaluating comics with critical tools best applied to painting either and that didn’t stop you.

Domingos — And what “decoding protocols” are you talking about? Ditto for the “critical tools” best applied to painting. What exactly are those?

How can one carry on an intelligent conversation about comics criticism when such protocols and tools remain undefined?

Pingback: Wertham and Are Comics Art? — is it 1981 again?

As for the latter yoy better ask Mike, he mentioned those, not me.

As for the former I explained myself in my comment.

“The object is of as much aesthetic interest as words in a novel. They’re there just to convey the idea.”

Depends on the writer. There is such a thing as poetry, outside of poems.

Finnegan’s Wake? Utterly sublime – though I barely knew a fraction of what I was reading, it was a devastating experience.

Not that I generally turn to comics for something like that. They are valuable to me in a way that officially sanctioned Art can never approach.

The Making Of left me dazed, but I need kicks too. I need irredeemable, incorrigible vulgarity, offensiveness and obscenity.

Take me to the carnival, if I get too much edification I’ll have to burn myself down.

” I need irredeemable, incorrigible vulgarity, offensiveness and obscenity.”

You can get that from any medium. There’s no reason to think that comics is better at those things than, say, film. Similarly, I don’t see why comics can’t do the things that high art can do as well as high art (assuming that you’re distinction between high art and vulgarity, offensiveness, and obscenity makes sense, which it actually doesn’t at all. Have you read Swift?)

You’re confusing the history of the form with its formal qualities, I’d say…or an idealized history of the form with formal qualities, perhaps.

History tends to inform practice, and reception.

It’s the mavericks of literature that bring us to exceptional places like Hassan’s Rumpus Room. In comics, it’s exceptional works which are considered worthy of discussion in polite company, if at all.

I’m not seeking to disparage something like Asterios Polyp, The Making Of, Fun Home, or any other socially ambitious graphic novel, I tend to enjoy them. I’m just grateful to the many artists who don’t supplicate to the myth to which you refer by that insidious marketing term: “high art,” and whose work is fueled by unreasonable demands and the basest, funkiest narcissism.

Swift’s great, but he’s always talking about something.

I love Johnny Ryan. But I love the film Airplane too. I love Destiny’s Child. The first of those is actually the one that is probably easiest to place in a context of critical validation.

In that he has consistency? He seems like he’s resting on his “laurels” (such as they are)to me, but I haven’t read much of the fighty stuff (just the first one), so I can’t really say a lot about that. The things he posts on Tumblr (a lot of penis-obsessed defacement, mostly) are funny but I much prefer the reader submissions in Viz, which are in a similar vein but less arch. His line is good, it’s maybe the most goofily accomplished thing about his work.

Airplane does it for me, in a corny old-fashioned sort of way – haven’t seen it for a while though.

Destiny’s child are way too ideologically compliant. I guess that makes them of value to cultural historians.

When I say “Viz,” I’m talking about the British comic, not the Manga company.

Briany: I said “novel,” not “poetry.” But yours is a good point. This is a flawed dichotomy if I ever saw one. So much so that I’m not sure if Duchamp was completely successful in that particular part of his work. I once saw a Duchamp bottle rack suspended from the ceiling and receiving light from above in order to draw shadows on the floor. That, to me, was a huge betrayal of the work’s intentions. So, ideas it is, but we can’t control how people will feel or not feel in front of a work of art.

I meant that words can function poetically even if the form isn’t a poem – and even if they are simultaneously operating in another mode.

“Riverrun…” etc

To Duchamp’s finely cultivated eye, the urinal may have been appreciated in any number of ways – poetic, formal, ontological, whatever – but to most of us there remains a certain urinal residue. (Couldn’t resist.)

Brian Eno pissed in it – what an oaf!

Would he sit on an inverted chair?

I agreed with you Briany.

I did notice that, but I thought the idea of poetry being a potential of language in general needed reasserting because of your:

‘ I said “novel,” not “poetry.” ‘

and I wanted to share the Eno anecdote, obviously.

Sometimes I can be quite civilised.

Briany, the point about Johnny Ryan is that he’s just working in a mode that maps pretty easily onto high art values. Part of it is the line — the inky spontaneity of the drawing is definitely auteurish. Part of it is the underground scatology — shocking the bourgeoisie is (despite your suggestion to the contrary) a really sure way to identify yourself as a bourgeoisie participating in the high art tradition.

Airplane and Destiny’s Child are a lot more easily low-brow, precisely because of the corniness and the “ideological compliance” that you point out.

In other words, your argument that comics is uniquely un-high-art because it’s offensive and oppositional is really confused. Offensive and oppositional is how high art defines itself in a lot of cases. If you wanted to make a case for the unique unhighartness of comics, you’d need to point to the corny meaninglessness of Archie, maybe, or Dilbert, I guess.

But the truth is, even given its fairly low status, comics has a history of lots of different kinds of modes, so insisting that it is uniquely oppositional or uniquely lowbrow or whatever ends up being pretty arbitrary in the end.

I don’t think I was being anywhere near as essentialist as you seem to be suggesting. EG, I acknowledged a few graphic novels I’ve enjoyed that at least serve as placeholders for the literary, the fine, even the ‘high’ if you must insist.

Personally I think the bourgeoisie are no more likely than anyone to be shocked by Johnny Ryan’s un-unique brand of puerility. I never advocated him as being some sort of Avant-Garde figure anyway, I thought that was what you were doing (I was wrong, though). As I said, the reader submissions in Viz come closer to having the kind of virtue one might charitably associate with Ryan due, in some part, to their lack of hipster striving.

I really don’t know about this idea that ideological compliance is the preserve of the low-brow. First I should clarify that I was referring to dominant-ideology compliance. Then one obvious counter-example is Trade Union banners. (Low-brow craftsmanship wedded to class-consciousness.) From there you can follow through revolutionary poster art, Rosta, Folk-Art in general, Art-Brut – there’s no positive correlation between low-brow and ideology until you get into mainstream commercial work and all the other state apparatus.

Comics do indeed operate in many different modes, I said as much, but what I am advocating is not the same as the mode you seem to think I’m talking about.

I very deliberately used the words ‘irredeemable’ and ‘incorrigible’ and (although this may muddy the waters if taken from a certain angle) I might add to those, ‘delinquent.’

In other words: demanding rather than desiring; unethical, unreasonable; absolutely not what the doctor ordered.

“How could I be “missing the point” that it’s lack of “rigor” being criticized, when no one has brought up “rigor” as a standard for criticism?”

In purely loosely defined terms, “rigor” is one thing that most good critics look for when discussing art. It’s pretty much ‘Criticism 101.’

Actually, if you want to know the truth I meant “rigor” as in “rigor mortis.”

“In other words: demanding rather than desiring; unethical, unreasonable; absolutely not what the doctor ordered.”

Right. And I just don’t see any way to see that as characteristic of comics. Superman is unethical? Fun Home is unreasonable? And Peanuts seems very much what the doctor ordered to me.

Destiny’s Child is anti-stalking and pro women not taking shit from their boyfriends. Is R. Crumb less ideologically compliant because he’s more misogynist? Or what?

Folk art and art brut and trade union banners are completely high brow beloved.

———————–

Domingos Isabelinho says:

Mike: “If the “Fine Arts” world would can seriously call some canned Artist’s Shit, or a light switch being flipped on and off, or — on a wittier level — a urinal mounted on a gallery wall, “art,” I don’t see why not.”

If you want to criticize (Dadaist, neo or not) Conceptual art you better get your decoding protocols straight.

———————–

Am I attempting a critical analysis and evaluation? Hardly. (Check out my original comment in context.) Merely pointing out that such creations — whatever the means by which they achieve aesthetic effects — qualify as “art.” The degree of quality does not affect whether something is “art”or “not.”

————————

You can’t “read” a conceptual work of art as if you were reading a painting or a sculpture…

————————

Certainly. But, it’s still possible, in the case of the canned Artist’s Shit (“Critics, prepare your ‘decoding protocols!’ “), or a light switch being flipped on and off, to tell when a work is mediocre.

————————–

No one mentioned “rigor,” but no one mentioned evaluating comics with critical tools best applied to painting either and that didn’t stop you.

————————–

“Painting” was mentioned as an clearly-stated analogy to the likewise absurd practice of critiquing comics with the same standards applied to prose.

—————————-

steven samuels says:

[Mike says] “How could I be “missing the point” that it’s lack of “rigor” being criticized, when no one has brought up “rigor” as a standard for criticism?”

In purely loosely defined terms, “rigor” is one thing that most good critics look for when discussing art. It’s pretty much ‘Criticism 101.’

—————————–

Well, then…there are no critics here! I can’t recall a single HU critique where “rigor” was brought up as a standard for why a work succeeds/fails.

Mike: See above for an explicit value judgment. I just saw it coming, but you’re right, sorry for the misunderstanding.

Mike, again: ““Painting” was mentioned as an clearly-stated analogy to the likewise absurd practice of critiquing comics with the same standards applied to prose.”

Not exactly. Standards weren’t the point, social legitimation was.

———————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

Mike, the thing is, Eddie says Suat is complaining that comics aren’t literature…but that’s not what Suat actually did in his essay.

——————-

To be precise here, the “comics” dealt with in the original articles (https://hoodedutilitarian.com/2012/09/ec-comics-and-the-chimera-of-memory-part-1-of-2/ , https://hoodedutilitarian.com/2012/09/ec-comics-and-the-chimera-of-memory-part-2-of-2/ ) were the EC comics, not comics in general.

In part 1 of that essay, Ng Suat Tong writes:

——————-

[A young EC fan is quoted] “….If any popular writing deserves a claim as literature, this does also.” [Needless to say, this argument is not viewed with sympathy, but dismissed “on cold hindsight.”]

…Over two millennia ago, Aristophanes was brilliantly mocking the tragedies of Euripides (Women at the Thesmophoria) and risking prosecution with forthright attacks on the leaders of Athens. Contrast this with what we get in Mad…

[Re the EC horror comics] I am not suggesting that children should be deprived of profane fantasy but the finest children literature (and this is what is being claimed for EC) does not permit such concerns to overwhelm a certain truthfulness and sophistication…

In the 1950s, Bradbury was writing alongside the likes of Robert Heinlein, Arthur C. Clarke, Fritz Leiber, Brian Aldiss, and Alfred Bester. Later years would bring us the classic works of Philip K. Dick, Harlan Ellison, John Brunner, Ursula K. Le Guin, J. G. Ballard, Roger Zelazny, and Gene Wolfe. Beginning with their imaginations and ideas, these writers charted a path through literary science fiction into acute considerations of the artistic aspects of their chosen genre.

Science fiction in American comics, on the other hand, is dead. Quite frankly, there is little we should expect from a genre where a handful of weak fantasies created in the 1950s are still seen as the bench mark for all future works. Rather than advancing with the literary giants in the field, comics writers and artists have been crippled by the conservative and unenlightened trends so prevalent till this day…

“Master Race” is not an exercise in pure experimentation like Richard Maguire’s “Here”, nor do such forays into experimentation and formalism forbid coherent, fully evolved content. Is it not possible, for example, to find substance in Godard’s Weekend or Bunel’s Discrete Charm of the Bourgeoisie?

Shouldn’t we entertain a degree of embarrassment for placing the EC War stories alongside some of the finest works of war literature; classics like The Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Pat Barker’s Regeneration trilogy, Catch-22 and The Naked and the Dead? Would we honestly trade a film collection consisting of Apocalypse Now, Paths of Glory, Ivan’s Childhood, La Grande Illusion, or Ran for the entire collection of EC war comics?…

I return to Goya and The Disasters of War….

——————

In part 2, we read:

——————-

The difference between the majority of the EC War stories and modern war comics is that, in comparison to the great works of war literature (and film)…

…when it comes to children’s literature, a proper account must be taken of their accessibility (both emotionally and intellectually) and limitations…A comic prepared for an adult will therefore often fail miserably as art for children. It is precisely within the parameters of children’s literature that a few of Kurtzman’s war stories can be deemed of some merit.

——————-

(Emphases added)

…So one can see, with all the flinging about of the “L” word, where Mr. Campbell (and, I suspect, more than a few others) would’ve gotten that impression.

——————–

Ng Suat Tong says:

In my view, comics crafted for children and comics crafted for adults must be judged using different criteria. The exact nature of these criteria is not within the scope of this reply, suffice to say that when it comes to children’s literature, a proper account must be taken of their accessibility (both emotionally and intellectually) and limitations. A work that does not meet or work within these criteria must be deemed bad children’s art. A comic prepared for an adult will therefore often fail miserably as art for children. It is precisely within the parameters of children’s literature that a few of Kurtzman’s war stories can be deemed of some merit.

———————–

The problem with this at first reasonable-sounding bit is that “children” and “adults” are considered consistent, unchanging objects. All in their group supposedly with the exact same intelligence, levels of sophistication, tastes. All wanting to read the exact same “category-appropriate” (you can’t even same “age-appropriate,” because factors such as the difference in literary tastes between a five-year-old and a ten-year-old are ignored) stuff all the time.

Don’t children and adults, actually remarkably varied groups of individuals (even if one can generalize), enjoy — to put it in culinary terms — steak one part of the day, cake another? Can appreciate both a gourmet feast and the down-to-earth pleasure of a hot dog?

When a child is reading “Where the Wild Things Are,” and an adult reads the same work, don’t in general they bring different qualities to the work as readers?

I can appreciate the brilliance of Tardi’s and Sacco’s war stories (which are rightly praised in that critique), and delight in the excellence that frequently (though far from always) appears in the EC war comics.

It ought to go without saying, that even in the same art form, different works aim for different aesthetic effects. To look at Mexican pulp magazine covers ( http://monsterbrains.blogspot.com/2012/01/mexican-pulp-art.html ) in the same fashion one would look at a showing of Braque’s canvases would be ludicrous.

From the current defense of his case:

————————–

I would ask interested readers to read the article he cites to see for themselves if I have denied Kurtzman’s talent for cartooning as Campbell’s hysterical pronouncements seem to suggest.

—————————