Google “jennifer egan” and seconds later the term “metafiction” will attach itself leech-like to the side of her postmodern head.

I know this because members of my university have made the possibly foolhardy decision to ask me to give a talk on the Pulitzer winning author for our 2013 Tom Wolfe Weekend Seminar. I’m to place A Visit from the Goon Squad into “the context of contemporary American culture” with “a discussion of Egan’s special skills as a writer,” keeping in mind she will be “sitting right there in front of you.”

I regularly tell my first year comp students that even if we could materialize authors in our classroom (usually during a discussion of Henry James’ mind-blowingly ambiguous The Turn of the Screw), their opinions would be completely irrelevant. Readers and only readers determine the meaning of a text. Except of course in this case. Because that will be the actual Jennifer Egan. In the front row. Listening. To me. Blathering. About her book.

Poetic comeuppance aside, the author’s physical presence will be especially apt for a discussion of Goon Squad. Chapter one opens: “It began the usual way . . .” and before you’ve waded in a dozen pages you’re knee deep in self-referential story-telling, overt comments about symbols and plot arcs and collaborative writing. Ms. Egan is pulling off her metaphorical mask and yelling: Look at me!

So now, after stretching to pluck David Lodge’s The Art of Fiction from my office book shelf, let me flip to Chapter 46: “Metafiction is fiction about fiction: novel and stories that call attention to their fictional status and their own compositional procedures.”

Apart from a requisite nod to the 18th century’s Tristram Shandy, Lodge spends most of his time chatting with John Barth and Kurt Vonnegut. William Gass coined the term in 1970, after Barth demonstrated the style in his 1968 novel Lost in the Funhouse. Slaughterhouse Five was published a year later. Add Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 (1966) and a couple of short stories by Robert Cover, and there’s your course syllabus for “Goon Squad: Founding Fathers of American Metafiction.”

Except, wait, here’s that inevitable moment, my weekly plot twist, where I veer to where I must always veer:

Superheroes!

No, no, no, NO. American metafiction did NOT begin in the late 60s. It was not a highbrow literary phenomenon. It was the lowest of the lowbrows, the pulpiest of the pulps, that ultimate literary stepchild, the comic book.

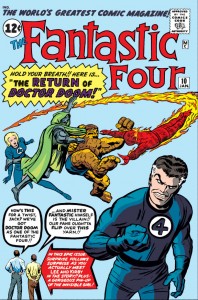

Stan Lee and Jack Kirby beat Pynchon by a half-decade. In Fantastic Four #2, on newsstands in 1961, Reed Richards convinces an alien race not to invade Earth by showing them drawing of monsters. “Those are some of Earth’s most powerful warriors!” he tells them, while thinking, “I pray he doesn’t suspect that they’re actually clipped from ‘Strange Tales’ and ‘Journey into Mystery!’” Two other Marvel titles sharing newsstand space with Fantastic Four.

Two issues later, the Human Torch chances onto a stash of old comics. “Say! Look at this old, beat-up comic mag! It’s from the 1940’s!!” It features the Golden Age Namor on the cover. “The Sub-Mariner! . . . He used to be the world’s most unusual character!” And guess who shows up two panels later?

In issue five, Johnny’s reading habits have expanded. Reed asks, “What are you reading, Johnny?”It’s The Incredible Hulk #1, out the same month. “A great new comic mag, Reed. Say! You know something—! I’ll be doggoned if this monster doesn’t remind me of The Thing!” Because he’s supposed to. Marvel created Hulk because of the Thing’s popularity.

The cover of FF #9 asks: “What happens to comic magazine heroes when they can’t pay their bills and have no place to turn?” But #10 is even bolder: “In this epic issue surprise follows surprise as you actually meet Lee and Kirby in the story!!” The authors stare up at the action from the front row.

Stan: “How’s this for a twist, Jack? We’ve got Doctor Doom as one of the Fantastic Four!!”

Jack: “And Mister Fantastic himself is the villain!! Our fans oughtta flip over this yarn!!”

As promised, Dr. Doom uses the Marvel duo to lure Reed into a trap.

Johnny: “Phone call for you, Reed! It’s Lee and Kirby! They’d like you to go to their studio to work out a plot with ‘em!”

Reed: “Strange…we just finished discussing a new plot yesterday!”

Thing: “Tell ‘em if they don’t stop makin’ me even uglier than I am, I’m liable to go up there and wrap this two-ton weight around their skinny necks!”

Issue 11 goes further still. The team has to stand in line to get a copy of their own comic book, and then they go home to answer fan letters, shattering the last remains of the fourth wall. Mr. Lumpkin, their mailman, laments in the final panel: “Blankety blank fans and comic magazine heroes, and letters to the editor pages! Ohhh my achin’ back!”

The trend dies a quiet death in the next issue when the Hulk shows up with no mention of that comic mag John had been reading. Marvel traded in metafiction for multi-title continuity. That brings us into 1962, still eight years before Barth coins the term.

And does all of this put Jennifer Egan into “the context of contemporary American culture”?

Um, no, not really.

So you’ll forgive me if I sign off now and finish reading Goon Squad.

‘Nuff said.

You’re not seriously trying to claim American metafiction began in 1960s comic books are you? You can’t possibly believe this.

Should I read this article as a satire of a marvel comics fan?

It seems fairly tongue in cheek…he does mention Tristram Shandy, after all…

Even in comics there are predecessors. Winsor McCary has a Rarebit Fiend strip where the character is tormented by McCay himself. And (in animation) there’s Duck Amuck….I’m blanking on highbrow examples, but I’m sure they exist….

I’m assuming that this was at least somewhat tongue-in-cheek. After all, even limiting oneself to comics, it’s pretty easy to find earlier examples, e.g. Kurtzman’s Hey Look! strips etc. That said, the FF example is certainly an amusing example of the concept. Perhaps something was in the air in 1961? After all, The Flash of Two World’s also appeared that year, wherein the Earth-2 Flash was originally known to Barry Allen as a comic book character only to be discovered living on a parallel world!

I’m definitely going to have to read David Lodge’s book though. As it happens, I just started re-reading his novel Changing Places last night and so he’s been on my mind. Does he mention other examples in between Tristram Shandy and Vonnegut/Pynchon et al? Again, off the top of my head, I came up with I Claudius; and surely Borges belongs in there? Even Huck Finn mentions that readers may already know him from Tom Sawyer and of course Tolkien had some fun with the concept, with Bilbo Baggins’ own written account of his adventures in The Hobbit being called into question by characters in LOTR (and yes, now we’re in “unreliable narrator” territory! Woo hoo!).

And is I Claudius highbrow or middlebrow? It’s pretty trashy in places! :-)

How is “I, Claudius” matafictional?

Shakespeare is definitely metafictional, btw

The whole premise (IIRC) of I Claudius is that it’s Claudius’ own account of his life that Robert Graves somehow discovered. Seems to fit the bill to me.

Well Shakespere and I Claudius aren’t American but if Shakespeare counts Don Quixote counts….

Who’s Winsor McCary?

Don Quixote was originally written by Cide Hamete Benengeli.

Metafiction is probably as old as fiction, older if you include other genres, metatheater, etc. But the term was only invented in 1970 as a rather highbrow literary category. I’d argue that its most immediate influences were from pop culture, including such lowbrow creatures as comic books. But Stan Lee is no source point either. As I continue to research this topic, I’ll test the hypothesis that his FF metafiction is influenced from 1950s Mad magazine. But even Bob Kane’s earliest Batman comics have meta moments, so it’s present from the beginning of the medium too.

I thought Pierre Ménard wrote it.

(Don Quixote, that is.)

1961-62 seems like a fertile time for the concept. Nabokov’s Pale Fire (which surely qualifies) was published in 1962. The fact that Nabokov was originally from Russia should hardly disqualify it, even if one is to focus on American writers since he was (I believe) an American citizen by then.

But it seems like once you start thinking about it, examples aren’t hard to find, high, low, or middlebrow. Do Lovecraft and Robert Chambers count, since several of their best-known works are concerned with a fictional book within their “universe” (Lovecraft’s Necronomicon and Chambers’ The King in Yellow)?

The Pierre Menard example is great, since it’s sort of meta-meta (if you will), with Pierre Menard rewriting a book that is itself credited to a fictional author.

Otto Binder and C.C. Beck (and their assistants) included metafictional elements in some of the Golden Age Captain Marvel comics. Captain Marvel Adventures #20, for example, includes the story “Capt. Marvel and the Revolt of the Comics,” in which a group of comic strip characters go on strike (the artwork in the story, however, looks as though it could be by Pete Costanza and not by Beck himself). There is also a cover of one of the later issues of the series where CM is being erased; you can find a nice color reproduction of that image in Chip Kidd’s Shazam! book.

In the first issue of the early 1970s Shazam! series, by the way, Denny O’Neill and Beck include Binder himself in a cameo appearance, as the writer catches up with the ever-youthful Billy Batson. The two haven’t seen each other, of course, since the early 1950s (due to the National vs. DC copyright case, but that’s another story!).

I remember that Shazam! appearance by Binder! DC did a few other stories along these lines in the early seventies, including a two-part JLA/JSA crossover that featured writers Cary Bates, Elliot S! Maggin and Julie Schwartz as characters on “Earth Prime”. I believe Cary Bates also wrote himself into at least one Flash story.

Barry N. Malzberg’s strange novel Herovit’s World is about a science fiction writer and his relationship not only with his main character in a long-running series of pulpy SF novels, but also with a seemingly independent persona based on his own pen name, the putative author of the SF novels.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_metafictional_works

Thanks, Brian, very useful leads. I was also reading in “Men of Tomorrow” of an issue of Superman in which Clark takes Lois to a movie that starts with a Superman cartoon and he has to prevent her from seeing the scene where Clark in the cartoon turns into Superman.

That Earth Prime story sounds really interesting, Daniel. Do you remember the JLA issue numbers in which it appears? I may have to track those down!

I just remembered that Roy Cook wrote a post on authorial avatars in comics over at Pencil, Panel, Page just a couple of weeks ago. Roy also raises some good questions on the use of metafictional strategies in comics:

http://pencilpanelpage.wordpress.com/2013/03/14/can-we-trust-authorial-avatars/

@Chris, the Superman cartoon story was reprinted in Superman from the Thirties to the Seventies, and perhaps elsewhere.

@Brian, the various Earth Prime stories are covered here:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Earth_Prime#DC_Comics

That’s a great Superman story, Chris–thanks for the reminder. I remember first reading a b&w copy of it in the _Superman from the ’30s to the ’70s_ hardcover collection and loving its inventiveness. It was almost a blueprint for Alan Moore’s 1980s Superman stories.

Who wrote that story, by the way? Was it Binder? Or does it not have a credit? Binder brought a lot of his ideas and concepts from his years at Fawcett over to the Superman Family comics in the 1950s.

Thanks, Daniel! & you beat me to the _Superman from the ’30s to the ’70s_ reference. Copies of that collection are still fairly easy to find inexpensively on Amazon and eBay, especially ones without the dust jacket.

Brian, according to Gerard Jones, it was still Siegel writing Superman then, mid 40s I think.

Thanks, Chris! I need to go back and re-read that one. It’s a lot older than I thought it was.

The Flash metafiction predates 1961. The first image of Barry Allen in Showcase #4 is of him reading a Flash comic.

Good point!

The Eisner/Feiffer Spirit story where Feiffer appears as a character who murders Eisner and then does a Clifford story with Clifford as The Spirit is another nice early (1950) comics example.

Just wanted to weigh in in support of Don Quixote. That’s probably the first “modern” metafictional novel and, for my money, the most complex of the bunch.

If this is becoming a conversation about metafiction through the ages, I heartily recommend Francis Beaumont’s Knight of the Burning Pestle (1607/1613) in which a couple of nouveau riche audience members get up on stage during a play and proceed to rewrite it according to their (terrible) tastes.

Its not a literary example, but there’s a large tradition of painters painting themselves, as in Velazquez’s Las Meninas. Also, the murals of Diego Rivera.

Speaking of Fantastic Four and metafiction, wasn’t there a story in which the Impossible Man held the Marvel bullpen hostage and made them rewrite the story that was currently taking place? Was that in the Lee/Kirby run of Fantastic Four or a later creative team?

Concerning comic books, there is Al Williamsons nice story The Aliens (from Weird Fantasy 17, 1952), where some aliens on a destroyed earth get to see a comic book that contains the very story we are reading, and on the last page the aliens, exclaiming “Squa Tront! Spa Fon!”, see themselves reading the last page reading the last page … Great mise en abyme!

Of course there are masses of metafictional stories in early comic strips, the Rarebit Fiend piece Noah mentioned is only one of many examples. Of course the device wasn’t invented in comics, but it’s maybe the most metafictional art form ever …

Metafiction has been endemic to comics since their modern beginnings. Töpffer’s M. Pencil begins with the author’s cartoon blowing away into the world and thus starts the story. At least since then, comics have consistently been parodying themselves, from Cham Doré to McCay and Herriman, &on.

Regarding “Pale Fire”, either Lee or Kirby were clearly familiar with it when they created the X-Men, since they nicked Professor X’s civilian name from it.

Cham *and* Doré. Sry.

I haven’t read I Claudius, but the device of introducing a novel as a historical document that the author has discovered or edited doesn’t seem like metafiction to me. That device actually seems like the opposite of metafiction, since it lends veracity to the narrative instead of calling attention to it as fiction. I was just thinking about this, because I recently read Mother Night by Kurt Vonnegut, which begins with just that device, and the book’s Wikipedia page describes it as metafiction.

Maybe people are using the term in different ways? Someone mentioned Pale Fire. I think that one becomes metafiction on the last page, where Kinbote seems to realize that he’s a character in a novel by Vladimir Nabokov, but I don’t know about the rest of it.

(The last page of the commentary, that is. Come to think of it, Pale Fire contains references to Lolita in the poem, commentary, and index that are definitely metafictional.)

The wikipedia suggests that Pale Fire is a poioumenon, a subset of metafiction: “a term coined by Alastair Fowler to refer to a specific type of metafiction in which the story is about the process of creation.”

Kind of like Fellini’s 8 1/2.

Matthew:

“Speaking of Fantastic Four and metafiction, wasn’t there a story in which the Impossible Man held the Marvel bullpen hostage and made them rewrite the story that was currently taking place? Was that in the Lee/Kirby run of Fantastic Four or a later creative team?”

It was Roy Thomas, George Perez and Joe Sinnott, a very funny story. Stan and Jack cameo.

Maybe the oldest piece of metafiction is in the Mahabarata, the world’s longest poem.

At one point, one character needs some information so he looks up a sage, who quotes the relevant passage from earlier in the poem!

One more note about Pale fire, the poem that is the subject of the novel has recently been published as a standalone work, complete with commentaries on the poem and facsimiles of the original index cards that John Shade (the fictitious author) used in composing it:

http://www.gingkopress.com/09-lit/vladimir-nabokov-pale-fire.html

About ‘Quixote’:

As soon as Cervantes had Book 1 published, it became an immediate bestseller– not just in Spain, but throughout Europe.

Some hack, in those days before copyright law, wrote a spurious sequel. This angered Cervantes, who was spurred to write Book 2, concluding with the death of the Knight of the Doleful Countenance.

Along the way, Quixote and Sancho come across a copy of Book 1, and wax satirical and critical over it and its author.

There’s meta in the very first paragraph of ‘Huckleberry Finn’:

‘You don’t know about me without you have read a book by the name of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer; but that ain’t no matter. That book was made by Mr. Mark Twain, and he told the truth, mainly. There was things which he stretched, but mainly he told the truth. That is nothing. I never seen anybody but lied one time or another, without it was Aunt Polly, or the widow, or maybe Mary. Aunt Polly–Tom’s Aunt Polly, she is–and Mary, and the Widow Douglas is all told about in that book, which is mostly a true book, with some stretchers, as I said before.’

Incidentally, those first 20 issues of Fantastic Four should be remembered for a wonderful saving grace: they’re very, very funny!

In that answering-fan-mail issue, Reed and Ben actually turn to the reader and yell at him directly, for pooh-poohing the Invisible Girl (and making her cry)!

Parodied in 1963, where all of Infra Girl’s fan mail is about how she sucks and should quit the team.

Except in 1963, the fan mail is fictional, Marvel’s must have been real.

Re: Quixote, spurious sequel or “fan fiction”?

And here’s another example of poioumenon, the theme to Garry Shandling’s old TV show:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8cWbkWTYwTw

Actualy, the old Garry Shandling show was pretty much all-meta all the time: characters spying on each other on the studio monitors, etc.

Meta-fiction is just a fancy term for something that happens all the time, but the neologism gave academics and snobs a “cool kids club” cachet.

For gods’ sake, Aristophanes did it! (No kidding, go and read The Frogs. The entire point of the play is to dramatize a critique of other dramatists.)

American examples that predate Marvel Comics:

Buster Keaton’s Sherlock, Jr. (1924)

The climax of the Bob Hope comedy My Favorite Brunette (1947)

Groucho’s “strange interludes” in Animal Crackers (1929)

Various episodes of the 1950s radio show Richard Diamond, Private Detective, on a variety of levels, including a parody of The Maltese Falcon, a parody of Jack Webb (pre-Dragnet) that commented on both his performance style and a radio show he was popular in, and several direct references to the radio audience listening in to the show — within the story.

And those are just off the top of my head.

All the coinage of the term did was make the whole subject dreary, self-important, and academically “cool”.

(Wow, all I did was use the “cite” tag, and it borked my simple formatting. Your CSS appears to have at least one problem.)

Some “meta-artwork”: http://uploads3.wikipaintings.org/images/m-c-escher/drawing-hands.jpg …

The always interesting Laura Miller has some thoughts on this and related topics: http://www.salon.com/2013/03/29/sneaky_author_tricks/

More “meta-artwork”; from the brilliant Saul Steinberg:

http://www.adambaumgoldgallery.com/steinberg/DancCouple.jpg

The jarring juxtaposition of different drawing styles (“visual aliens, anyone?) calling attention to the “drawingness” of the work…

http://www.artcritical.com/carrier/images/Saul-Steinberg.jpg

http://graphics8.nytimes.com/images/2012/11/25/books/review/1125SOLOMON/1125SOLOMON-articleInline.jpg