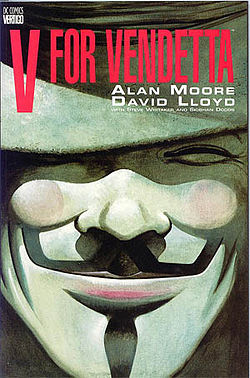

V for Vendetta, despite its pulp adventure plot and its stark propaganda, is not a morally simple book. The baddies, the fascists, are depicted as complex human beings with motives of their own, and sometimes even a kind of decency. V’s nemesis, Eric Finch, for example, is described in the text as “a policeman with an honest soul.” The hero, V, on the other hand, engages in any number of cruel and despicable acts — from systematic and serial murder, to the deliberate manufacturing of food shortages by sabotage, to torturing his young protégé, Evey Hammond, for the sake of producing a kind of conversion experience.

V for Vendetta, despite its pulp adventure plot and its stark propaganda, is not a morally simple book. The baddies, the fascists, are depicted as complex human beings with motives of their own, and sometimes even a kind of decency. V’s nemesis, Eric Finch, for example, is described in the text as “a policeman with an honest soul.” The hero, V, on the other hand, engages in any number of cruel and despicable acts — from systematic and serial murder, to the deliberate manufacturing of food shortages by sabotage, to torturing his young protégé, Evey Hammond, for the sake of producing a kind of conversion experience.

Isaac Butler, in his essay “V for Vile,” enumerates these and other various sins, both political and moral, at some length — writing, at times, not so much about the book as against it. In the comments to that post, others, such as Mike Hunter, counter that the character V may be reprehensible but the book implicitly condemns him and his actions. He notes, for instance, that V describes himself in the first chapter as “the villain” and is elsewhere identified with “the devil.” Such a defense, however, risks converting V for Vendetta from an anarchist book to an anti-anarchist book, one that can comfort timid liberals by equally condemning both political extremes. That reading not only undercuts Alan Moore’s stated intention (which may not be that important), it also ignores the story’s pervasive atmosphere of moral ambiguity, renders the ending arbitrary, and worst of all, prevents us from grappling with the genuine philosophical problems that the book poses.

Chief among these problems is, what may be the largest question in political philosophy since the time of Machiavelli, that of unjustifiable means. A great deal of evil has been done on the theory that some good will result, but looking back over history, it seems hard to defend the idea that the overall results have been good. And yet — what if evil means are the only ones available? More precisely, what if the means that might achieve our ends also contradict them?

In The Rebel, Albert Camus explains the paradox:

“If rebellion exists, it is because falsehood, injustice, and violence are part of the rebel’s condition. He cannot, therefore, absolutely claim not to kill or lie, without renouncing his rebellion and accepting, once and for all, evil and murder. But no more can he agree to kill and lie, since the inverse reasoning which would justify murder and violence would also destroy the reasons for his insurrection.”

One kind of solution, among the many that Camus considers, is that of the Russian terrorists who stand “face to face with their contradictions, which they could resolve only in the double sacrifice of their innocence and their life.” These martyr/assassins

“were incapable of justifying what they nevertheless found necessary, and conceived the idea of offering themselves as a justification. . . . A life is paid for by another life, and from these two sacrifices springs the promise of a value. . . . Therefore they do not value any idea above human life, though they kill for the sake of ideas. To be precise, they live on the plane of their idea. They justify it, finally, by incarnating it to the point of death.”

V is a terrorist of this mold. And so he plans his own murder — at the hands of the police detective Finch — just as meticulously as he planned his campaign of sabotage and assassination. V does, as Camus suggests, incarnate his idea to the point of death, but only so that the idea may survive: “Did you think to kill me? There’s no flesh or blood within this cloak to kill. There’s only an idea. Ideas are bulletproof.”

The idea of Anarchy does live on as, in a sense, V himself lives on — but in a new form, and in the person of Evey Hammond. Evey takes on the role of V, the mask and cloak, but her mission and her methods are different. She reflects: “I will not lead them, but I’ll help them build. Help them create where I’ll not help them kill.”

Evey’s new direction — her move away from violence — is only a renunciation of V’s methods, not of his vision, or even his plan. It is, in fact, the culmination of the latter. Earlier in the book, V himself acknowledged:

“Anarchy wears two faces, both creator and destroyer. The destroyers topple empires; make a canvas of clean rubble where creators can then build a better world. Rubble, once achieved, makes further ruins’ means irrelevant.

Away with our explosives, then! Away with our destroyers! They have no place within our better world. But let us raise a toast to all our bombers, all our bastards, most unlovely and most unforgivable. Let’s drink to their health. . . then meet with them no more.”

V’s dilemma, awful as it is, is that the methods that bring the new world into being stand in contradiction to the world they help create. Camus spells it out: “The terrorists no doubt wanted first of all to destroy — to make absolutism totter under the shock of exploding bombs. But by their death, at any rate, they aimed at re-creating a community founded on love and justice. . . .” Unfortunately, people who employ such methods may themselves be unsuited to live in the world they have helped to win. As Evey reflects, echoing V’s own words: “The age of killers is no more. They have no place within our better world.” The answer lies in V’s death. He must die so a new world can be born, a world where he is not needed and would not be welcomed.

V is vindicated, paradoxically, because he is condemned. V, the murderer, accepts his own murder in turn. And Evey — now, pointedly, “Eve” — becomes a new V, creator rather than destroyer. Violence is justified by the renunciation of violence. It is that renunciation that qualifies Evey for the new society, that justifies her efforts to build it. But V’s renunciation of violence is his suicide.

Camus’ solution to this dilemma — or rather, his resignation to it — was altogether more pragmatic, and more forgiving:

“Thus the rebel can never find peace. . . . The value that supports him is never given to him once and for all; he must fight to uphold it, unceasingly. . . . His only virtue will lie in never yielding to the impulse to allow himself to be engulfed in the shadows that surround him and in obstinately dragging the chains of evil, with which he is bound, toward the light of good.”

Camus, lyrically, leaves us with an image of the human condition: a solitary figure, bound in chains, surrounded by darkness, struggling toward freedom. As with his final view of Sisyphus — “The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.” — the image of the rebel is, perhaps, an optimistic one. For it suggests that we can resist the shadows, that the chains that bind us do not deform us with their weight, that we can recognize the light and do not grow blind in the darkness.

Camus suggests that struggle is possible, even where innocence is not, that we can assert our dignity even when we have not yet won our freedom. It is an ideal of heroism, not one of purity.

Bio

Kristian Williams is the author, most recently, of Hurt: Notes on Torture in a Modern Democracy (Microcosm, 2012).

“Violence is justified by the renunciation of violence. ”

I think this is in fact the way the book works…but I’m skeptical that that morality is a good morality. Does it justify drone strikes because Obama assures us that he takes them morally seriously? Is it better to be punched in the face by someone who declares he’s doing it for your own good? Is torturing Evey okay because V’s heart is in the right place?

Setting up the revolutionary as so all-knowing that he plans his own erasure just seems like a way to have your pulp violence and your sententious superiority too. Camus isn’t all knowing either, but I bet he’d have been able to see through this particular dodge.

Kristian,

Thank you so much for writing this. It’s really interesting to read a take on the material that tries to find some (qualitative and perhaps moral) good in it without explaining the troublesome bits of the book away.

Interesting…

Michael Walzer also brings up Russian Assassins (I’m assuming you’re talking about the anti-royalist assassins?) and actually offers them as counter-examples to terrorists of today, which he considers immoral. They showed restraint, which Walzer finds admirable. I recall Walzer using the example of how the assassins refused to assassinate adult nobility if their children were with them. He differentiates between assassins and terrorists because assassins showed restraints and had a moral code.

I think this article can also be summarized as “The Ethics of the Lesser Evil.” Have you read The Lesser Evil by Michael Ignatieff? He received a lot of backlash for it when he ran for political office in Canada (he wrote the book while he was at Harvard.)But this “one must sacrifice one’s own spirituality for the people” reasoning has been done in TV shows like Avatar, though the pay-off wasn’t quite as good, and Rowling’s Dumbledore was the patron saint of instrumentality, as far as I’m concerned.

But the thing about this comic is that V knows that what he’s doing is technically wrong, but he believes that the ends justify the means. In reality, there are a number of militants who justify THEIR MEANS as being totally just. If you look at Franz Fannon (not a militant, but his work is influential in IR ethics) he argues that oppression is systemic. In practice, that means violence against civilians is justified because they’re not innocent. If you look at Al-Qaeda’s ideology, they argue that Americans aren’t innocent because they live in a democracy and voted Bush in and consequently, they consider American citizens to be legitimate targets. The thing about terrorists is that they never call themselves terrorists. Even political philosophers grapple with who and what counts as a legitimate target. Governments are willing to argue that militant attacks against army bases are a form of terrorism, but I haven’t seen too many academics who agree.

I think we have this idea that these are topics that occupy militant minds, but I’ve seen them articulated more clearly by government officials than militants, especially when it comes to the question of state torture. Granted, I THINK early American anarchists may have had used the “means vs. ends” ideology, but my memory is fuzzy in this case and I don’t have access to my research right now to double-check. (N.B Ignatieff believes that Japanese Internment Camps were justifiable under the Second World War and he uses the ethics of the lesser evil to justify this position.)

Also, Eyal Weizman argues that “the lesser evil” is basically a boogeyman to justify state immorality. This article is excellent: http://www.e-flux.com/journal/the-least-of-all-possible-evils/

Anyway, I know this is quite a long response, so I will end it here.

A note about language: to talk about “unjustifiable” means, or actions being “technically wrong”, or means being “evil” is to beg precisely the question at issue. Of course the ends don’t justify the means if those means are unjustifiable. What is meant is something like “means that impose some harm on some moral patient”, where “harm” is understood very broadly; or, if you’re uncomfortable with such a broad notion of “harm”, “means that would uncontentiously be unjustified in at least the case where they were performed for something other than the greater good”. Since the latter is a ridiculously long thing to say, we might instead say “otherwise unjustifiable means”.

Maybe I’m crazy, but I can think of, like, a couple of cases where someone might think that maybe such means might have brought about the greater good: vaccination (which imposes a genuine, if small, risk on the patient), or indeed any kind of medical intervention ever (it’s a bad thing to cut people open and fiddle around with their insides!); the training of teachers and doctors (it’s a bad thing to knowingly provide worse service than what is otherwise available); voluntary euthanasia (it’s a bad thing to kill people!); incarceration, or indeed any kind of punishment by anyone ever, right down to merely inflicting damage to the “punished” person’s reputation (punishment by its very nature inflicts harm on the punished person — before anyone starts holding up the war on drugs or capital punishment as knock-down arguements, let me stress that the point is that at least some times some kinds of punishment, imposed by the state or other agents, have been justified — it would take a perverse moral disposition to deny even this weak claim about punishment); randomised controlled trials (similar to training doctors and teachers — it’s a bad thing to give people a treatment, viz. the placebo, when you have some reason to suppose that it’s worse than some other treatment that you could otherwise give); prosecution of civil rights (it’s a bad thing to make people do what they don’t want to do, as e.g. not serving “negroes” in their restaurant); the imposition of sanctions against apartheid; many forms of regulation (it’s a bad thing for the state to dictate what business can and can’t do); taxation of any kind (it’s bad to take things that belong to other people)…I don’t know, maybe there are some other cases?

–“But Hiroshima, eugenics, New Coke…”

Yes, there have been dickheads throughout history who have either used consequentialist reasoning as a smokescreen for their own interests, or mistakenly thought the ends justified the means when they didn’t. Such people are dickheads; V is obviously one of them. People throughout history have misused every moral position, and every piece of technology, so…?

Perhaps the argument is that there are certain kinds of actions that are never justifiable? Maybe so, but that means that the ends don’t always justify the means, which again appears to beg the question against the consequentialist. Which is fine, but that just means that the question is already settled.

Two quick replies, neither of which are likely to be very satisfying:

Noah- V and the Russian terrorists Camus describes aren’t just morally serious (as Obama may claim to be) and don’t just have their heart in the right place. They try to meet the demands of justice by also accepting the kind of treatment they dish out. In fact, V makes sure that he is killed.

Mr. Jones – It’s true that by making justice the main issue in his ethics he has already stacked the deck against consequentialism. The problem he poses is that, though murder cannot be made just, that doesn’t mean we can necessarily avoid it either. But yes, that’s a problem for deontologists and not for consequentialists.

Kristian, don’t you think it’s a problem to create a character who basically knows all and controls all, and then have him torture and murder people essentially on the ground that he knows best to such an extent that he’ll kill himself at the exact right time? It just seems awfully convenient.

That is…you’re saying that to be a rebel you have to be morally willing to repudiate your place in the revolution when the time comes. I’m suggesting that setting up your world so that the rebels are so morally superior that they’re allowed to do anything is the kind of utopian fantasy that excuses any level of violence.

Or to put it another way…saying that to be a rebel you must be a saint in practice pretty much inevitably means that anything rebels do is holy, up to and including (and indeed especially) torture, rape, and murder.

Noah — the moral argument isn’t mine. It isn’t even Camus’. It belongs to some 19th century Russians who, incidentally, didn’t succeed in starting a revolution. It also (I argue) belongs to a comic book character, V, and it seems to be endorsed by the narrative of which he is a part. That may mean the argument also belongs to Alan Moore, though some of his other work (most notably Watchmen) would seem to complicate his position.

In any case, the argument is not that the rebels are morally superior, nor that they are “allowed” to do anything at all. The argument is, precisely, that their actions are wrong, unjustifiable, yet necessary. Doing such things may make them heroes in something like the Classical sense, but it certainly does not make them saints. They have compromised their morality for morality’s sake, and they pay the price for doing so. V doesn’t just accept death as necessary, but as deserved.

Part of the problems probably lies with the fact that while V started out as a person/vigilante in Moore’s early years as a writer, he ended up more like a god-idea (with latter day Swamp Thing and Miracleman as his counterparts). So what began as an exercise in revenge and wish fulfillment (against a hated Conservative government) lands up being more a metaphor mimicking the known paths of revolutionary history. The thesis being that every revolution will have its victims and perpetrators, and that it is preferable that these violent men slink slowly away into the night (which they mostly never do). So I think Noah is right in saying that V for Vendetta is a utopian fantasy, but it’s a utopian fantasy which many liberals buy into (less the suicide pact). Which is why Sarah’s examples of Michael Ignatieff (a “liberal” imperialist) and Frantz Fanon (and his adherents) are so appropriate.

I do think Kristian nails the logic of Moore’s fantasy in his piece, though Moore partially repudiates this fantasy in Watchmen.

Kristian; deliberately dying for others is pretty much the definition of being a saint. Establishing your violent revolutionary as a saint seems to me really problematic.

And the argument from tragic necessity is, again, Obama’s argument for drone strikes, etc.

Right…I think Kristian does articulate what Moore is thinking. I just can’t help feeling that Moore’s thinking here is basically a moral atrocity and should be mocked.

I think the logic of Watchmen is pretty different. Veidt’s the V character, and Moore’s pretty careful to present him not only as a moral monster, but as a deluded nitwit obsessed with idiotic pulp narratives.

It’s probably true that Moore has too much affection for his character (and his ideology) to mock him thoroughly. His half-hearted fascist funeral for V at the end is more grand than pompous and ridiculous.

Noah – If “deliberately dying for others is pretty much the definition of being a saint” then Mr. Hyde from Moore’s League of Extraordinary Gentleman is also a saint. Either you need to revisit your definition or the category is morally useless.

I think what you really mean to say is that V is glorified — which he surely is. However, that is not the only attitude the text promotes, and it does not seem to be V’s final judgment on himself either. I just wanted, in my essay, to point out that there is a moral logic underlying V’s actions, and that the story does not simply celebrate them as good or condemn them as bad.

Violence is justified by the renunciation of violence.

Sounds like the plot of Gundam Wing.

Jones said: “A note about language: to talk about “unjustifiable” means, or actions being “technically wrong”, or means being “evil” is to beg precisely the question at issue. Of course the ends don’t justify the means if those means are unjustifiable. ”

I wish that was true, except then we’d have to throw out Kant’s contributions on Just War Theory (Re: Evil, which he uses quite regularly to describe certain “means” and whether they’re justifiable.)

What I’m talking about in my comment is that militants justify their actions by arguing that their means are totally a-ok.

Not everyone does that. Others argue that the benefits of an action (its consequences) outweigh the evil of its means. Eg. Extracting information through torture. It’s a cost/benefit calculation. Yes, the word “justify” basically means “to reason” in this case, but I also mentioned that militants “justify their actions as being totally just.” I know that’s a mouthful, but there it is. I never said V DIDN’T justify his means…I’m not sure if you were referring to me, but I thought I’d clear up any potential confusion, anyway. :)

Noah said: “Kristian, don’t you think it’s a problem to create a character who basically knows all and controls all, and then have him torture and murder people essentially on the ground that he knows best to such an extent that he’ll kill himself at the exact right time? It just seems awfully convenient.”

That’s curious, because one of the main argument against consequentialist thinking is that it is always looking towards a future that it can’t possibly control. Consequences happen in the future, so how do you decide what to do in the now?

In More’s work, V seems to have an unreasonable amount of control. He KNOWS what’s going to happen, but most people don’t know if the ends justify the means. They have to make a guess that x, y, and z are going to happen in the future. V almost seems to have un-human qualities, in this regard.

————————-

isaac says:

Kristian,

Thank you so much for writing this. It’s really interesting to read a take on the material that tries to find some (qualitative and perhaps moral) good in it without explaining the troublesome bits of the book away.

————————-

Indeed so; “double kudos”!

————————-

Kristian Williams says:

Earlier in the book, V himself acknowledged:

“Anarchy wears two faces, both creator and destroyer…”

————————–

I’m astonished I didn’t catch the connection earlier, but this is a clear nod to Hinduism, whose deities — rather than fobbing off the “destruction” part to baddies — frequently are creators and destroyers; cyclically destroying one world that another may rise in its place.

————————–

Camus spells it out: “The terrorists no doubt wanted first of all to destroy — to make absolutism totter under the shock of exploding bombs. But by their death, at any rate, they aimed at re-creating a community founded on love and justice. . . .” Unfortunately, people who employ such methods may themselves be unsuited to live in the world they have helped to win. As Evey reflects, echoing V’s own words: “The age of killers is no more. They have no place within our better world.”

—————————-

In, of all things, a Mickey Spillane book, his hero likewise reflects how he is the evil that destroys other evil, in order that the meek and good may inherit the Earth. (And then he Tommy-guns a bunch of Chinese Reds…)

—————————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

“Violence is justified by the renunciation of violence. ”

I think this is in fact the way the book works…but I’m skeptical that that morality is a good morality…

——————————-

Well, did even Alan Moore himself consider it a good morality, that the world should live by, or rather an interesting, far-richer and more complex story than one where the heroes are all Good and the villains all Bad?

I’d rather take V’s morality than nonsense such as pacifism, which only “works” if the side being opposed is not too bad and is concerned with public opinion. “Where Tutu (and Gandhi) got it wrong”; http://articles.latimes.com/2009/sep/24/opinion/oe-hier24

Speaking of Gandhi, from the brilliant (and alas, mostly-retired from cartooning) Tim Kreider; “Who Said It: Gandhi or Batman?” http://www.thepaincomics.com/weekly120125.htm

—————————–

Does it justify drone strikes because Obama assures us that he takes them morally seriously? Is it better to be punched in the face by someone who declares he’s doing it for your own good? Is torturing Evey okay because V’s heart is in the right place?

——————————

Well, the results make all the difference, don’t they? If getting punched in the face turns out to be the crucial tipping-point that gets someone who’s been a doormat all their life to fight back, gain self-respect and become assertive, wouldn’t that be worth it?

And, V didn’t just torture Evey; he orchestrated the experience, sneaking into her cell the inspiring autobiographical account of the slated-to-be-executed lesbian who proclaimed the torturers and executioners could not deprive her of that “one last inch” within which she could still be free. Which itself had transformed V in his cell.

Offered the opportunity, Evey refused to betray V — even though she believed it would mean her death — and thereby, painfully, realized she was capable of greater nobility and a heroic self-sacrifice she would never, under comfortable circumstances, have dreamt herself capable of.

Sure, it probably wouldn’t have worked in real life; but “V for Vendetta” is fiction…

In Nature, consider the “tough love” of the parental birds who peck at and drive off the fledgling from the comfy nest that’s all the world it’s ever known, so it may be forced to survive on its own and become an adult. (Come to think of it, V does just such a thing to Evey, leaving her stranded in a deserted street…)

——————————

Setting up the revolutionary as so all-knowing that he plans his own erasure just seems like a way to have your pulp violence and your sententious superiority too.

——————————

(SARCASM ALERT) At least there’s no “sententious superiority” to be found here…

——————————

Kristian Williams says:

Noah- V and the Russian terrorists Camus describes aren’t just morally serious (as Obama may claim to be) and don’t just have their heart in the right place. They try to meet the demands of justice by also accepting the kind of treatment they dish out. In fact, V makes sure that he is killed.

——————————–

Why, to a lesser degree, even Ozymandias, with his “sacrifice New York in order to save humanity from nuclear annihilation,” likewise accepts moral responsibility for the innocents he’d killed. “I make myself feel every death…”

——————————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

Kristian, don’t you think it’s a problem to create a character who basically knows all and controls all, and then have him torture and murder people essentially on the ground that he knows best to such an extent that he’ll kill himself at the exact right time? It just seems awfully convenient.

———————————

Again, “V for Vendetta” is fiction.

“Mrs. Christie, isn’t it awfully convenient for Hercule Poirot to notice that little detail…?

“Mr. Shakespeare, in order for ‘Romeo and Juliet’ to yank its audiences’ heartstrings, wasn’t it awfully convenient that the message to Romeo telling him of Juliet’s ‘pretending to be dead’ scheme went amiss?”

“I wish that was true, except then we’d have to throw out Kant’s contributions on Just War Theory”

Right, so what’s the down-side?

(j/k — haven’t read Kant on war, but he always makes for a good punchline)

Ha! I’m going to remember that one.

Hmmm…I think Hyde does end up as a saint, pretty much. He’s not as all powerful or all knowing as V is, though. But the comparison does suggest the extent to which our secular saints are created through war and violence.

I’m not sure why there being a moral logic means that the story can’t celebrate V’s actions as good? It seems like there needs to be a moral logic for the actions to be celebrated as good, actually.

Mike, Christie does stack the deck for Poirot, and Shakespeare’s plots are kind of notoriously contrived. Building a moral system around either of them seems like you’d want to take that into account. (And actually, in the final Poirot book, Curtains, Poirot behaves more or less like V…which raises similar problems, I think.)

Sarah…I think your point about V and means and ends is right. The fact that he knows all outcomes is a real problem for taking the moral system of the comic as seriously as Moore seems to want you to take it. Being all-knowing has major implications for what is permissible, in a way that makes any means justified. The comic does suggest that V’s morality is guaranteed by his willingness to die or remove himself…but I think the truth is that the real guarantor is his narrative privilege, the fact that he is never wrong and even organizes and anticipates his own demise. Knowledge is morality. (Again, in Watchmen, Veidt claims to know everything — but the comic undermines him, which also undermines his moral claims.)

Hegel, via Zizek, has the Terror not as an excess, oversight, or compromising blight, as a necessary element of instituting the revolutionary State. Like Marx saying you need imperialism in India in order to have trains, and trains are good.

And I like Zizek and Hegel. But all this consequentialist discussion does illuminate the point that knowing the future does eliminate the risk of action and non-action. Martin Luther justified official bloodshed and financial usury on the same basis (although the usury ban obviously had some apocalyptic consequences).

Just wondering if people are thinking about the difference between necessity and justice, and thus between pleasure and morality. In real life horrible things really are just going to keep happening, via a combination of necessity and pleasure. In stories, which is where justice and morality come in, the choice to sanctify violence is one that is not compelled in favor of violence. If Alan Moore wants to erect a deep nuanced justification for violence, I find that troubliog– more so in V than in Watchmen.

Isn’t the deck stacked for Jesus? And, yet, people still draw moral conclusions from that. On the other hand, maybe we shouldn’t …

And I think the word Noah is wanting is ‘martyr’. Not all saints are saints because they died for others, either in the popular sense of the word or the more technical one, right?

One last thing: reading V from a consequentialist perspective kind of robs it of drama. The idea of corrupting oneself for the commonweal just seems so much heavier. It’s even heavier if he believes in a soul, where he’s risking his own eternal damnation (e.g., Bonhoeffer was very dramatic). Consequentialism is kind of cold, like a business transaction, which is probably why a lot of people have a problem with it.

Martyr might work better.

Lots of people, like Nietzsche for example, don’t want you to draw moral conclusions from Jesus. I’m not exactly sure what you mean by saying that the deck is stacked for him, though? I mean, he gets crucified; he loses. It’s about him not being able to control events — even as God. That seems fairly different substantively from V’s logistical divinity…? I mean, Nietzsche’s objection to Jesus is exactly the opposite — i.e., he’s not sufficiently competent and controlling.

Wow, that was an eloquent and thoughtful essay that provoked really insightful comments, especially from Jones and Sarah. Okay, that’s enough cheerleading for now — on to my now-predictable long, moralistic post. They tell me awareness of the problem is the first step toward recovery.

Charles, I think we can all agree that we want to avoid anything that makes V even heavier. And I’m still in favor of drawing moral conclusions from Jesus. In his case, the omniscience does not detract from the moral significance; it multiples it. He not only knows what the outcome will be, he knows how much it will cost. Of course, you could say the same thing for V, but for probably obvious reasons, I dislike the comparison.

I think one of the questions that Jones brings up is where the difference is between what is unpleasant/distasteful/morally complex/just plain ugly, and what is actually wrong. I think this is one of life’s big, important questions, and consequentialist or not, consequences matter. If the SS are at your door, the right thing to say is that you haven’t seen any Jews, even if you’re hiding them in your basement. When moral absolutes collide (e.g., tell the truth versus protect innocents), I think the consequences on real human beings decide which one gives way. I know real world examples are rarely so clear-cut, (Jones’ are messier and more relevant to us in daily life) but that’s what makes it a good illustration, darn it. And so in real life, some imperfect forecasting is required to make those moral calls….which brings me to drones.

Noah, I know you’re very much against drone strikes in Pakistan, but I’m not sure why you seem to be more against those than you are other airstrikes on terrorists. Regardless of target location or whether the aircraft is manned, dropping a bomb on an enemy combatant (lawful or unlawful) is a process subject to the same international laws governing conflict. (See this link for a good overview of the topic, and jump to page 12 to get to the meat: http://www.icrc.org/eng/assets/files/other/law1_final.pdf ) Those laws are heavily influenced by the aforementioned Just War theorists, of whom Kant was but one. In said law, noncombatants cannot lawfully be the target. This is the point that V inconsistently, but egregiously violates — and to no real advantage, I think. A planner as advanced as he was could have kept the civilian populace off his target list and perhaps achieved his goals even faster.

Anyway, noncombatants can lawfully be killed incident to the attack, but the attack must be against a militarily necessary target. Furthermore, the scale and scope of the attack and the foreseeable resultant collateral damage must be proportional to that necessity. So a greater likelihood of civilian casualties may be acceptable when the attack is against a key operational planner than against a local cell leader.

The only difference with drone strikes in Pakistan is, well, they’re in Pakistan. Noah, is the fact that they’re across Afghanistan’s eastern border (i.e., outside the delineated war zone) what makes them so offensive?

Noah, I think Charles’ point is that Jesus wins, because the whole thing plays out exactly as planned — even, counter-intuitively, the part where he gets tortured to death. Nietzche misread the source material, I think.

Wow, now I’m making Jesus sound like V. I’ll shut up now.

“he gets crucified; he loses.”

1 Corinthians 15:55-57

Well, I didn’t shut up for long.

The passage in 1 Corinthians 15:55-57 starts off with Paul referencing Hosea, the Old Testament prophet. “Where, o death, is thy victory? Where, o death, is thy sting?” He goes on to explain, “The sting of death is sin, and the power of sin is the law. But thanks be to God! He gives us the victory in our Lord Jesus Christ!”

This is clearly post-game trash talk from the winning side. “‘Sup, death? Is that all you got? Is that your best shot? I didn’t feel nothin’! My man Jesus got yo’ number, dawg!” That’s a paraphrase, of course.

John, I think drone strikes in Afghanistan are monstrous as well. I’m sure we’re doing other dreadful things around the world too. Pointing out one dreadful thing doesn’t mean it’s worse, or that I approve of all the others.

For more unsportsmanlike conduct from the same author, read Romans 8:31-39.

In addition to John and Dean’s point about Jesus’ victory on the cross, I’ll just note that while Jesus dies for other people’s sins, V dies for his own. So by Noah’s earlier definition of Saint, V wouldn’t qualify because there’s no clear sense in which he dies “for others.” I think he would still count as a martyr, though, since he does sacrifice himself for a cause.

Okay, Noah, that clarifies it some, and I apologize for assuming a distinction where you made none. But how are either of them morally worse than the bombing of German industry in World War II? That was far less discriminate, with far greater civilian casualties, primarily because the technology was so much less precise. It seems like your real complaint is about war in general and the fact that people die. That’s completely valid, of course, but I think I’ve even seen you argue that war is necessary sometimes.

I generally detest affected ebonics, but that is a compelling paraphrase of Paul. Aw snap.

G,K, Chesterton has the whole thing about the group of anarchists in The Man Who Was Thursday that turn out to be (spoiler alert) policemen– the intended rub being that intellectual criminals are the most amoral and therefore evil, but you also get the auxiliary conclusion that the guardians of order are the last step of cynicism of crime beyond criminality. So you get Christ as the ultimate transgressor, denying sin and death and therefore being consumed by it– and denouncing God in the agony of death.

But the only life he sacrificed was his own, which is perhaps the only life that is ours to dispose of honestly– and even then, it’s a borrowed and shared gift.

I’m pretty sure V is dying for others. He’s killing himself so that the revolution can succeed, right? That’s how I read it, anyway, and that seems like your point about his need to erase himself for the greater good. It seems clear to me, anyway, that he’s sacrificing himself for the greater good.

I think there’s actually a fair amount of theological question about what sense Jesus can be said to have planned his death. C.S. Lewis in his space trilogy argues forcefully that seeing it that way is pretty thoroughly misguided…basically because having Jesus turn into V is a heresy (from his perspective.) That is, humans have free will; God isn’t controlling them. Good came out of Jesus’ death on the cross, because God is good, but the killing of Jesus was still evil; Judas is not a pawn of Jesus the way that V’s killer is his pawn.

I mean…V clearly is meant to be a Christ analog to some degree. But he’s a Christ analog who substitutes violence, murder, and rape for turning the other cheek. That’s a pretty stark moral contrast it seems like — and I think a deliberate one. Stanley Hauerwas talks a fair bit about the choice between the church and the church of violence.

I think carpet bombing Dresden was pretty heinous. So were Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

I vacillate between pacifism and Just War. I don’t think there’s much argument for the drone strikes even on Just War grounds, though. Just War is pretty firm about the need for proportionate response, and the fact that you really are not supposed to kill people unless you’re in imminent danger. None of those people crawling around Pakistan or Afghanistan are an imminent, immediate danger to US interests, much less US civilians. You don’t get to kill civilians over there on the off chance that someone standing nearby might kill civilians you care about sometime in the future. The threat of terrorism doesn’t justify you becoming a terrorist.

Drones could possibly be justified on Niebuhrian grounds — i.e., politicians must make difficult choices, balancing good and evil, etc. I bet Niebuhr himself would not be particularly impressed with that argument in this instance; he was pretty cognizant of how imperialism works. If Obama bothers to justify these things to himself at all, though, I’m sure he does it on Niebuhrian grounds. Which is why everyone in power loves Niebuhr, unfortunately.

V does die so that a new world, without people like him, can come into being. But I don’t know that anyone in particular benefits from his death, or is even meant to. He’s disqualified himself, by his actions, from the world his actions help to create. He dies because, by his own lights, he deserves to. That’s all rather different than the Jesus story.

Badiou compares Paul to Nietzsche partially because Christ is, in Paul’s view, “beyond good and evil.” Because of Christ, nobody “deserves” punishment, any more than anyone “deserves” wealth. This is not the only way of viewing Christ– he did after all say that he came not to overturn but to fulfill the Law. But judgment, while not eliminated, and in some ways intensified, is nonetheless indefinitely suspended. This really takes some wind out of straightforward ethical readings of his legacy. V by comparison seems pretty straightforward– a superhero/Ubermensch/Napoleon figure, who is only beyond good and evil because he is just special like that, according to himself.

Kristian, I think V and Jesus are very different too! I think Moore still posits him as a Christ figure, though…precisely because, as you say, he dies so a new world will come into being.

Chesterton and Lewis! I love you people!

Bert, if it helps, in my head Paul was a suburban white kid affecting the over-the-top ebonics. I think your points from the Chesterton story are excellent, and ”the last step of cynicism” — I am totally feeling that one. I think Jones is, too, based on his list above of the awkwardly unpleasant things we do to be good. Your line, ”But the only life he sacrificed was his own, which is perhaps the only life that is ours to dispose of honestly– and even then, it’s a borrowed and shared gift,” is outstandin. That’s the difference I never expressed above nor even fully articulated in my head.

Noah, I’ve read some Narnia and several of Lewis’s non-fiction works, but I have not read the space trilogy. Now I have to, to confirm that my hero’s reading of the Passion is that different from mine. When I read the Gospels, I see a series of engineered and even tightly scheduled events leading up to the Crucifixion Jesus clearly had planned well in advance. Every step from allowing Lazarus to die so he could miraculously heal him (and thus confirm his threat to the religious leadership), to which questions he answered at the Sanhedrin and in front of Pilate — it all seems calculated to provoke a specific decision. His frequent predictions seem pretty clear in retrospect, too. None of that, in my mind, negates free will. I’m both predictable and transparent, and people who know me often know what I will say or do before I do it. That doesn’t mean they control my actions (wait…or does it?). Anyway, as I have been allowed to believe that it was my idea to say, this is God we’re talking about — the one who Exodus says ”hardened Pharoah’s heart” because He had a few points He wanted to make…publicly. He’s the only one who can be consequentialist, because He knows the consequences, and humans aren’t the only ones doing hard things for good reasons. Besides, if someone’s culpability was mitigated by either engineered circumstances or direct divine influence — well, He is the righteous judge, so we can be sure that will be taken into account.

Noah, this debate motivated me to do some research on the current status of the drone strikes. (http://edition.cnn.com/2013/04/11/world/asia/pakistan-musharraf-drones/?hpt=hp_t2; http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drone_attacks_in_Pakistan). I was not aware that targeting had changed to include “signature” strikes, based on what is considered behavior. I hope that the more cautious descriptions of tareting are still true. I understand, based on media reporting and public statements by both government officials and insurgents, that for years the people targeted in the drone strikes were actively planning and preparing attacks on Afghans, Pakistanis, and even Americans. Their intended victims were not just military, but as you specify, even civilians. The sites were identified training camps and terrorist headquarters. I hope that even now, that is still largely or entirely the case. The people on such sites are much more culpable than conscripted Wehrmacht and much more dangerous than the ball bearing factories at Schweinfurt, although they were both lawful targets. Admittedly, the ball-bearing factories were a poor use of resources for little effect. I make no excuses for Dresden. I think Dresden an excellent *bad* example of not only proportionality, which you cite correctly, but also humanity, another principle of the law of armed conflict. I don’t want to touch Hiroshima and Nagasaki, since we all have our own favorite “What If?” story on that one. Plus, even if one can argue for the military necessity of a course of action that killed hundreds of thousands and inflicted keloid scars on the survivors — who wants to?

Going back to Afghanistan, if this is imperialism, it’s the shoddiest possible version. We spend money on Afghanistan, we help them get to their raw materials, but then instead of taking those materials, we help the Afghans develop a processing capability and move up the value chain so they get all the cash. We do this because we want a functioning state, not a failed one that becomes a safe haven for Al Qaida again like it was in 2001. Some people might argue we’re trying to build a future market for Ford and Apple. That’s giving America a lot of credit for planning, and I think that would actually be a good use of power (like the Marshall Plan was). But that’s like saying the Steinbrenner family donates to Children’s Hospitals so the sick kids can be Yankees prospects some day. It might happen, but the odds are too long for them to make the bet. For anybody who’s still listening, we didn’t invade Iraq for oil, either. We were already getting Iraq’s oil at a discount through the UN’s oil-for-food program. We can talk about all the good or bad reasons we went in. We can even cry over the way we wound up at that policy the way you end up at a Denny’s at 2:30 in the morning and can’t figure out why, but it wasn’t the oil.

“Based on what is considered behavior” in third full paragraph above should read “based on what is considered suspicious or telltale behavior.” Noah, if you could correct it please, I’d appreciate it. I’m aware that you might believe it’s more accurate as it stands.

———————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

Mike, Christie does stack the deck for Poirot, and Shakespeare’s plots are kind of notoriously contrived.

———————–

(Sarcasm Alert) Nice to be clued in about the argument that I had just made!

———————-

Building a moral system around either of them seems like you’d want to take that into account.

———————–

(Looks around) Has anyone rhetorically “buil[t] a moral system around” “V for Vendetta”?

(Ah, the classic “accuse somebody of making some outrageous/absurd statement which they in fact did not make, then attack them for making an outrageous/absurd statement” tactic!)

———————–

The fact that he knows all outcomes is a real problem for taking the moral system of the comic as seriously as Moore seems to want you to take it.

————————

But, does that a creator “seems to” — by some folks’ estimation — favor a certain way of behaving, actually translate into seriously believing it, and trying to push that “moral system” as The Way Things Ought To Be?

Why, one would then think that Patricia Highsmith, in her Tom Ripley books, was then advocating murderous amorality…

And do you really think that Alan Moore truly believes that V’s pet cause, Anarchy, would in the sorry-ass real world lead to anything but bloody, horrendous chaos?

————————-

Being all-knowing has major implications for what is permissible, in a way that makes any means justified.

————————-

One could go on a theological bend with that one!

But say, suppose you knew that in a few years someone would die a hideous, agonizingly painful and prolonged death. Would it not be arguably a morally defensive action to kill them now, and save them the suffering?

————————-

Bert Stabler says:

G.K. Chesterton has the whole thing about the group of anarchists in The Man Who Was Thursday that turn out to be (spoiler alert) policemen…

————————–

Arrk! At least you had the “spoiler alert”; wish I hadn’t been reading so fast…

—————————

Noah Berlatsky says:

…V clearly is meant to be a Christ analog to some degree. But he’s a Christ analog who substitutes violence, murder, and rape for turning the other cheek.

—————————-

Ah, yeah, the “rape” thing. Just like James Bond forcing Pussy Galore to kiss him was likewise repeatedly described as “rape.” ( The actual scene: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1pUXH1Bye88 )

Sorry, but slinging accusations of “rape” all over the place (“He forcibly grabbed her butt! RAAAAPE!!!!!”) doesn’t heighten the masses to the heinousness of the act, it just “devalues the currency” by grouping the actual, vile crimes with far milder stuff.

And, don’t feminists say “rape is an act of hate, not sex”? Well, where was the hate — or sexual interest, for that matter — in V’s, while impersonating a jailer, “examination” of Evey, no different than is given to anyone being imprisoned? The very act which is now being called “rape”?

Feminist say it’s an act of violence. It doesn’ have to be about hate. The Steubenville rape; those guys didn’t seem particularly filled with hate. You can inflict violence out of indifference, or because it’s fun, or because you feel like it. Hate doesn’t have to have anything to do with it.

John, the discussion of free will and god’s will and predestination is mostly in the second book (Prerelandra, I think). They’re all amazing, though.

But not as good as Till They Have Faces, his last novel written with his wife, which is I think one of the great novels of the 20th century, and criminally underread. Also, perhaps not coincidentally, it’s Lewis’ only feminist novel, and one which is comfortable with non-traditional gender roles as well.

Anyway…drone strikes. I’ve seen a couple places that one reason they target you is if you attend the funeral of someone who was killed in a drone strike. It would be nice if that weren’t true.I don’t have any trouble believing it is though.

Re: imperialism. Imperialism doesn’t have to be about markets. It can be (and often is) about safety and hegemony. Control has its own logic. We invaded Iraq mostly because we were pissed after September 11 and felt like it. It didn’t have much to do with oil, nor with any particular American interest. We just had all these guns and wanted to use them. That’s imperialism too.

Noah’s comment is as good an excuse as any to trot out those well known sentences by Joseph Schumpeter in his chapter “Imperialism in Practice” (from The Sociology of Imperialisms, 1918):

“There was no corner of the known world where some interest was not alleged to be in danger or under actual attack. If the interests were not Roman, they were those of Rome’s allies; and if Rome had no allies, then allies would be invented. When it was utterly impossible to contrive such an interest—why, then it was the national honor that had been insulted. The fight was always invested with an aura of legality. Rome was always being attacked by evil-minded neighbors, always fighting for a breathing space. The whole world was pervaded by a host of enemies, and it was manifestly Rome’s duty to guard against their indubitably aggressive designs. They were enemies who only waited to fall on the Roman people. Even less than in the cases that have already been discussed, can an attempt be made here to comprehend these wars of conquest from the point of view of concrete objectives. Here there was neither a warrior nation in our sense, nor, in the beginning, a military despotism or an aristocracy of specifically military orientation. Thus there is but one way to an understanding: scrutiny of domestic class interests, the question of who stood to gain.”

That’s pretty great. I think the point is too that the people who have to gain by the exercise of power are the people who have power. An imperial nation is a more centralized, more authoritarian nation, almost (or even not almost) inevitably. Therefore the people in power always have an interest in exercising authority. The military wants to show that it’s worthwhile spending all that money on guns; the President wants to show he’s a strong leader; etc. Power has its own logic and its own inertia.

To which Jesus says, give up power…and V says, exercise power, but then give it up at the exact right moment. Jesus’s advice is supposed to be less practical, though I’m not exactly sure why….

Noah and Ng, I’m used to people throwing imperialism around as an epithet that means land or resource acquisition. I’d seen the broader definition you’re using in a Robert Kaplan book, but didn’t realize that was what you meant. As such, I would not challenge its use in reference to American foreign policy. Of course, the insecurity is often justified. As Rome learned, the Prom Queen attracts a lot of attention, much of it negative.

Regarding the Lewis books, thanks very much. I haven’t even gotten to Graeber yet, but my schedule should open up soon, and I have a birthday coming up, so I think HU has made my list for me.

Regarding the drone strikes, I find the idea that someone would be targeted merely for attending a funeral extremely difficult to believe. It would be a flagrant and severe violation of the law of armed conflict and would involve way too many people for a proper criminal onspiracy. On the other hand, I have no problem believing that one terrorist might predictably attend another terrorist’s funeral, and once identified, become a target. I hope they don’t read HU.

Regarding Jesus’s way (The Way, in New Testament language), you and Ng already explained why people see it as less practical, since it involves an immediate loss of control. We all have our little empires.

I received a DVD of a dramatized debate between Freud and Lewis as a gift. It’s called The Question of God, and PBS produced it. I haven’t watched it yet. Have you (collective you, I.e., “any o’ y’all”)? I suspect it will be awesome, but it’s four hours, and I’m already giving up some sleep just for HU.

And I forgot to add regarding Jesus’s way, that voluntary loss of power is one of the reasons faith is a requirement – and such a difficult one.

Haven’t seen Freud vs. C.S. Lewis. That sounds great though.

And, just fyi…Ng Suat Tong’s given name is “Suat”; Ng is the family name.

Don’t get your hopes up. I’ve seen the play based on the book and it’s entertaining without being especially intellectual. There’s only so much depth you can fit into a play. The PBS documentary might be better. Some of the criticism I’ve read that the deck was stacked against Freud in this production/imagined meeting is not far from the truth. Also, I don’t think I’ve seen Freud held up as a great advocate of the atheist side of the equation much before. He’s hardly a factor/bugbear in mainstream Christian Apologetics at least.

Oh well. So much for that.

I think Freud was a bigger deal in Christian apologetics at one point. Now it’s all about Darwin though, and scientists more or less lump Freud with the religious whackos, as far as I can tell….

Suat, I apologize. Now I’ll never forget. And thanks for the info on the play. I think, if I were making this, I might pick Bertrand Russell as Lewis’s adversary. The more modern equivalents would be Sam Harris or maybe Daniel Dennett, who seems a more sympathetic personality for the audience. I always thought that Dawkins and Hitchens made terrible arguments, just setting up pathetic straw men and then acting as if they were fighting dragons. They’re more about pep rallies than substantive debate. But I picked up a couple Sam Harris books once and was immediately impressed. He is a serious opponent of religion.

Sam Harris seems pretty douchey to me. Freud is way more interesting than any of those guys. The “religion has done good things” vs. the “religion has done bad things” argument doesn’t deal with the main issues of why intelligence narrativizes reality, and the subsequent recursive weirdness of transcendently narrativizing that impulse.

Little parenthetical comment: did you know there was a fourth C.S.Lewis Ransom novel, never finished — ‘The Dark Tower’? In it Ransom and friends, at Oxford, have a device that can look into parallel dimensions. In one such, they see an army of demons, headed by an arch-demon with a rotating horn on its head called the Unicorn, busy building an exact replica of Oxford University…That fragment drives me nuts– what a hell of a terrific premise for a Lewis fantasy/allegory!

Have to agree with Bert. Sam Harris seems like the atheistic equivalent of a right wing fundamentalist. The kind of person who gives atheists a bad name.

Yep! I’ve got that…should reread it.

Apparently Lewis was horrified when various people pointed out the Freudian implications….

I’ll third the Sam Harris sneering. Hitchens’ prose is at least fun to read.

You know Harris believes in reincarnation, right?

Oh man, I love that Lewis fragment The Dark Tower. There’s been some debate over its authenticity, and frankly some of it seems a little un-Lewis-like, but it’s a great little story, even if it’s just “in the manner of” Lewis(Ransom fanfic?). It seems to me that there’s an obvious implied ending, but I’ll keep that to myself for now.

Noah, I did not know Harris believed in reincarnation — so he’s radically atheist, but believes in the immortality of the soul? Does he also accept the moon landings as genuine, but believe the Earth is flat?

Bert, “douchey” nicely sums up why I thought audiences might be unsympathetic. And I think your next point is valid. Saying God isn’t real because believers did bad things is like saying you don’t believe in kangaroos because you don’t respect the aborigines who told you about them. (Wait, didn’t something like that actually happen when Australia was first colonized?). Regardless, I don’t think rhetorical logic approves of bias against the source as evidence.

My understanding is that he’s sort of a Buddhist…which isn’t incompatible with being an atheist, but which maybe is incompatible with mocking other people’s religion, and is definitely incompatible with apologizing for torture, which he also does.

I’m interested in your concise construction of “power”, Noah.

In particular, the idea that we can “give up” power is interesting to me. By power here do you mean the legitimate exercise of force?

Also, for the record, I find your argument that “we went into Iraq because we had guns and we just wanted to use them” to be reductive. I think that a nuanced and complex approach should be used to meet the challenge of an event like that.

“My understanding is that he’s sort of a Buddhist…which isn’t incompatible with being an atheist, but which maybe is incompatible with mocking other people’s religion…”

Do you object to the mockery of religion? You just said,

“I just can’t help feeling that Moore’s thinking here is basically a moral atrocity and should be mocked.”

I think that’s a lucid moment, but that stupid comic takes on moral & social issues that religion also gets into and is just as capable of being crapheaded and scary about.

Owen: I’m pretty sure Noah is all for complexity with regards the Iraq war. It’s just that his main point is rarely brought up in relation to that event. Afterall, the more “enlightened” (cf. Cheney/Bush) Madeline Albright was widely reported to have written the following in her memoirs concerning a preceding war:

“What’s the point of you saving this superb military for, Colin, if we can’t use it?”

Owen, I think the call for subtlety or nuance in these matters can sometimes just end up as a way to not have to say anything at all. I think we went into Iraq because we were freaked out, because we had guns, and because people who spend their lives trying to get into power like to exercise power. I don’t see much evidence that there was a profit motive. Nor is there much evidence that any actual American interests were threatened by Hussein at any point. Psychological explanation about Bush and his father seem inadequate. I’m sure people disliked Hussein and felt he was a bad person, but we fund and support lots of bad people (including Hussein, at one point.)

If you’ve got a better explanation, I’d be happy to hear it articulated. But calling me out because the tone of my offhand blog comment is insufficiently academic seems kind of silly.

Deelish, I wasn’t saying that religion should never be mocked. I was saying that mocking religion is a weird thing for a Buddhist (even an atheist Buddhist) to do. Not that I’m an expert on Buddhism, but it has a long, long history of syncretism; it’s just not exclusive on issues of doctrine the way Western religions tend to be.

Basically, the militant atheism Harris, etc., practice seems like it comes out of a tradition of radical Protestantism, historically and intellectually. It just seems like it sits really oddly with Buddhism.

Actually, many Buddhists I know (white and raised in secular post-Christian households) are fairly bitter about Christianity. I think the observation that atheism is often Protestant doesn’t prevent Western Buddhism from also being fairly Protestant, much less mystical and more iconoclastic than older Buddhist traditions.

1) I too picked up a Sam Harris book once and was immediately impressed, by what a nitwit he is. He really does seem, in Suat’s words, “the atheistic equivalent of a right wing fundamentalist […] The kind of person who gives atheists a bad name”. And that’s exactly why atheists need him — why should the opposition have all the rhetorically dishonest sophists and charismatic demagogues?

Not really kidding here. Unreasonable idiots are usually the people who set the boundaries of public debate; when only one side has idiots, while the other is all mealy-mouthed and reasonable, the public sense of possibility and “truth in the middle” shifts in the direction of the former, even if the other side really is the one being epistemically responsible. Witness what has happened to political reality in the US over the last two decades, while the “reality-based community” worried about trifles like truth and accuracy.

The other advantage of your Harris or Dawkins is that they give atheist teenagers, and other mental adolescents, someone to latch on to, and a way to construct their identity as oppositional to the mainstream. Seems like a good thing.

2) Freud is a good choice of foil for Lewis for the time; as Noah says, he used to be a bigger deal in apologetics but, now being lumped with the nutjobs, can be generally ignored. Hard to think of another public intellectual at the time who was so famously atheist; Russell is the only alternative that comes to my mind. Freud has the extra advantage of having purported to explain the origins of religion.

3) Bert, if you’re still reading…hand on my heart, this is not a diss, but I have next to no idea what you mean by “why intelligence narrativizes reality, and the subsequent recursive weirdness of transcendently narrativizing that impulse” or what Freud has to do with it. If you’ve the time and inclination, could you maybe elaborate a little? I’m really curious.

Lots of “Eastern” Buddhists are also bitter about Christians. Apparently, Christians can be pretty hateful people. Not to mention the fact that Sri Lanka is supposed to be 70% Buddhist but we all know what happened there right? I guess Buddha wouldn’t be so special if liberation from Samsara was quite so easy.

Noah: OK, it just seemed from your statement as if you were expressing disapproval of the mockery of religion in itself. I’d hate to live in a society where that was even more discouraged. My understanding is that Harris finds value in the spiritual experience of loss of self and merging with the universe that many people in different cultures have experienced, but he wants to unhook that from mythologies about God and life after death. I don’t think he’s a Buddhist. I think he has done some really important work in interrogating the intellectual dishonesty of religious claims, especially as they keep finding their way into the mainstream media (like that neurosurgeon peddling a book about having experienced proof of the afterlife in a coma, and who I saw serve up his swill completely unchallenged on a CNN panel) but his aggressive line about Islam has been counterproductive and naive about the ways societies use their holy handbooks.

However, let’s let him speak for himself:

http://www.samharris.org/site/full_text/response-to-controversy2

Noah, if I ever get accused of having one major flaw, I hope it’s that I take the things you say casually too seriously.

Come out to NY, let’s get that drink.

” For anybody who’s still listening, we didn’t invade Iraq for oil, either. We were already getting Iraq’s oil at a discount through the UN’s oil-for-food program. ”

We got our oil, and tens of thousands died in the process.

And at least a few people might disagree with your last statement (via Glenn Greenwald

Gen John Abizaid– “Of course it’s about oil, it’s very much about oil, and we can’t really deny that.”

Chuck Hagel– “People say we’re not fighting for oil. Of course we are. They talk about America’s national interest. What the hell do you think they’re talking about? We’re not there for figs.”

Alan Greenspan– “I am saddened that it is politically inconvenient to acknowledge what everyone knows: the Iraq war is largely about oil.”

“We invaded Iraq mostly because we were pissed after September 11 and felt like it.”

It’s all of the above. Check off every box. It was because of 9/11, oil, Israel, arrogance and of course ignorance. And of course the evangelical POV cannot be discounted. It’s all of the above for the terrorists from Wyoming/Texas, and it’s all of the above for the terrorists from Saudi Arabia and elsewhere.

“As Rome learned, the Prom Queen attracts a lot of attention, much of it negative.”

The prom queen has invaded and heavily interfered with dozens of countries. Unlike Rome, no one has invaded us. All in all, based on recent and past history I’d say we’re the barbarians.

“I find the idea that someone would be targeted merely for attending a funeral extremely difficult to believe.”

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2013/apr/11/three-lessons-obama-drone-lies

I think the reason we’re focused on the middle east in general has to do with oil. I don’t see what advantage we got in invading Iraq per se at that particular time. But maybe I’ll read those links and they’ll convince me….

And Bert and Suat, fair enough about bitter atheist and violent Buddhists.

———————–

John Hennings says:

As Rome learned, the Prom Queen attracts a lot of attention, much of it negative.

————————-

Indeed; “Uneasy lies the head that wears a tiara!”

————————–

Regarding the drone strikes, I find the idea that someone would be targeted merely for attending a funeral extremely difficult to believe. It would be a flagrant and severe violation of the law of armed conflict and would involve way too many people for a proper criminal onspiracy.

—————————

So it’s legally OK if they’re just “collateral damage” rather than specifically targeted…

—————————

Bert Stabler says:

The “religion has done good things” vs. the “religion has done bad things” argument doesn’t deal with the main issues of why intelligence narrativizes reality…

—————————

Um? I’d think the answer is obvious, it’s just a side effect of that useful for survival “pattern recognition” thing, which helped distant ancestors note there was a lion lurking amid the bushes, or see reality in the form of narratives (“UG went out of the cave after dark, and got eaten as a result!”) rather than scattered events with no causality whatsoever.

—————————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

Owen, I think the call for subtlety or nuance in these matters can sometimes just end up as a way to not have to say anything at all.

—————————-

Thus, it’s better to toss out simplistic, incendiary arguments rather than risk not saying anything about a subject? Okaaayy…

From Tim Kreider; http://i1123.photobucket.com/albums/l542/Mike_59_Hunter/MySlogan.jpg

—————————-

Jones, one of the Jones boys says:

I too picked up a Sam Harris book once and was immediately impressed, by what a nitwit he is. He really does seem, in Suat’s words, “the atheistic equivalent of a right wing fundamentalist […] The kind of person who gives atheists a bad name”. And that’s exactly why atheists need him — why should the opposition have all the rhetorically dishonest sophists and charismatic demagogues?

Not really kidding here. Unreasonable idiots are usually the people who set the boundaries of public debate; when only one side has idiots, while the other is all mealy-mouthed and reasonable, the public sense of possibility and “truth in the middle” shifts in the direction of the former, even if the other side really is the one being epistemically responsible. Witness what has happened to political reality in the US over the last two decades, while the “reality-based community” worried about trifles like truth and accuracy.

—————————-

Brilliant, superbly put! I tip my hat in admiration…

Come to think of it — I’d not read ahead to Jones’ comment while digging up that link to the Kreider cartoon above — doesn’t the wimpy body-language and expression in Kreider’s self-portrait therein, the mass of nuanced argument, replete with caveats and footnotes, look like exactly the kind of thing Boobus Americanus would sneer dismissively at?

“Narrativizes” is my neologism for “constructs narratives to understand.” Which has nothing to do with escaping from lions– plenty of insects have fight-or-flight “pattern-recognition” impulses that work just fine. There’s obviously no large agreed-upon narrative; science provides rational speculations without meaning, while most other traditions (Buddhism included) provide meaningful statements without descriptions that are rationally convincing. So the fact is that nothing is resolved, except that we need to do this, and then we apply some story to why we (not just individuals but societies) need to do this, either within or in lieu of a coherent image of the cosmos. “Nothing is resolved” is in itself not an unreasonable conclusion, except then you get into the kind of “why even utter the thought” kind of nihilist solipsism that I and my fellow teenage atheists were prey to.

Oh, and Sam Harris’ assholery as a good in itself because it moves the world closer to atheism is only true if you already believe his contention; i.e., that the world is somehow improved by moving closer to atheism.

I don’t see any evidence for that. Faith has its atrocities; atheism has its atrocities; faith has its injustices; so does atheism.

Harris advocates for idiotic Islamophobia, torture, hatred, and intolerance. He’s a fool and a bounder. Arguing that stupidity and viciousness are okay as long as it’s your guy advocating them is pretty much the definition of partisan hackery, which doesn’t generally lead anywhere good no matter who’s engaged in it, as far as I can tell. I admire the contrarian elan of Jones’ formulation, but I think it’s basically sophistry.

steven, the Guardian article essentially says people can be targeted for their behavior without their actual name being known, but it offers only hyperbolic speculation as to what that identifying behavior is. If it were merely attending a funeral, then everyone at the funeral would be targeted, which wouldn’t require precision weapons from a drone loaded with sensors at all. That’s more a sixties era carpet bombing problem. A more modest solution would be an artillery barrage like you might use against an enemy battalion encamped in the field. And after that happened exactly twice, no one would go to funerals in western Pakistan anymore. My point is that what you’re suggesting would not only be against the law of armed conflict and the rules of engagement, it would make no military or even common sense.

Mike, yes, it’s legally okay, as long as the military value of the target is proportional to the expected collateral damage. As a speculative example, if the target is directing operations that kill dozens of people a year, then maybe killing the other people in his car with him is an admittedly tragic, but acceptable loss. Precision weapons make the standard much tougher, since they make targeting small areas accurately so much easier. In World War II, bombing runs would destroy multiple city blocks to take out one large factory — not because there was much military value in killing or injuring city blocks’ worth of mostly civilian Germans, but because they couldn’t avoid the collateral damage and still hit the factory. Now they can destroy one or two key pieces of the factory. Civilians still die, but in much smaller numbers. Again, the International Committee of the Red Cross has a great article on this. The effect of precision weapons on the acceptable collateral damage standard begins about nine pages into it, but the whole thing’s pretty illuminating. Please see URL below.

http://www.icrc.org/eng/assets/files/other/irrc_859_schmitt.pdf

Noah, thanks for being the atheist who pointed atheists have atrocities, too. In the twentieth century, tens of millions were killed in the name of godlessness, and many tortured as well. Some estimates indicate that many more have been killed in the name of atheism than have been killed in the name of God. Of course, to be fair, church atrocities had slowed to a relative trickle by the time the industrial revolution came along.

Bert: “science provides rational speculations without meaning, while most other traditions (Buddhism included) provide meaningful statements without descriptions that are rationally convincing… ‘Nothing is resolved’ is in itself not an unreasonable conclusion, except then you get into the kind of ‘why even utter the thought’ kind of nihilist solipsism that I and my fellow teenage atheists were prey to.”

But science and religion aren’t the only cultural conversations devoted to finding meaning, and no atheists argue that science should become the only cultural conversation about meaning (or that it’s about meaning in the first place.)

Nihilist solipsism is a disingenuous & cynical position to take, but the fact that sentiments like “nothing means anything, so I’m going to get mine” tend to be met with hostility doesn’t suggest a thriving school of thought, nor does that message seem to be prevalent in culture & the arts even on a coded level. Our culture is very concerned with finding meaning, direction, and applying justice. Now, of course people will behave cynically without advertising it, but the news I get doesn’t make it look as if cynical, irresponsible behavior is less prevalent in the more religiously saturated parts of our culture, or even that there’s a balance.

‘“nothing means anything, so I’m going to get mine” tend to be met with hostility doesn’t suggest a thriving school of thought, nor does that message seem to be prevalent in culture & the arts’

deelsih, do you ever listen to any contemporary pop, especially hip-hop? Nihilism is flourishing. I have students in my class (low-income youth of color) making comics (a fwe, not just one) in which the hero is wealthy.

Faith has not solved the world’s problems, but the smigness of contemporary atheism is hard to admire.

“Smugness.” dammit.

” My point is that what you’re suggesting would not only be against the law of armed conflict and the rules of engagement, it would make no military or even common sense.”

Yes. It would be, and it is. Are you denying that innocents have not been killed as part of the drone wars? You’re free to assume good faith, but the details on the ground completely contradict your point of view. No hyperbole, just facts.

It’s worth pointing out that imperialism and violence often don’t make any military or common sense. Iraq didn’t. Incompetent imperialism is still imperialism.

And the main point about imperialism, as Suat’s quote says, is that it’s not about military or common sense. It’s about domestic politics. There are reasons for leaders to look “strong”, and those reasons are often more important than whether a policy is actually doing anything worthwhile.

No mass killings have occurred because of atheism. What is this, evangelical radio?

Charles — Pol Pot, Stalin, Mao, Ceucescu (sp?), etc.

steven, — If the sources of your “facts”are articles like the ones in The Guardian, then I think you’re being misled. I’m not denying that innocents have been killed. I’m not denying the possibilty of error. I’m denying that they’ve been intentionally targeted. You’re accusing people of murder. Have you ever met the people who do this? Do you have direct knowledge pf their operations? These are strong accusations on scant information, about operations that can involve dozens, if not hundreds of Americans. Do you really think so poorly of the men and women recruited by the armed forces?

There have been several articles in recent years where reporters quote insurgents on how effective and disruptive the attacks have been. I don’t think that would be true if the military were just bombing things to show effort and “look strong.” If one is deployed to Afghanistan or Iraq, there are plenty of legitimate insurgent targets to choose from. They hide among the populace, so it takes a massive intelligence effort to find them, but they’re there.

Charles, are you serious? Communism is an atheist philosophy. For pity’s sake.

They even kill people on the basis that they’re religious, occasionally.

Come on, John, you really believe Stalin and rest killed mainly to promote atheism? Why did they kill atheists, then?

Communists are atheists. Communists kill people. Communists kill because they’re atheists.

There’s an airtight argument.

But seriously, commies killed for all kinds of reasons, mostly having to do with possessing a totalitarian mindset that would brook no disagreement with the guiding ideology. This means that they would kill religious believers because of their beliefs, yes. But to bean count every single death that can be traced back to Stalin or Mao or Pol Pot and summarize all of it as “because the victims were not atheist” is really just flimflam sophistry, created by the religious right for their own persecution agenda over here.