The index to the Comics and Music roundtable is here.

_______________

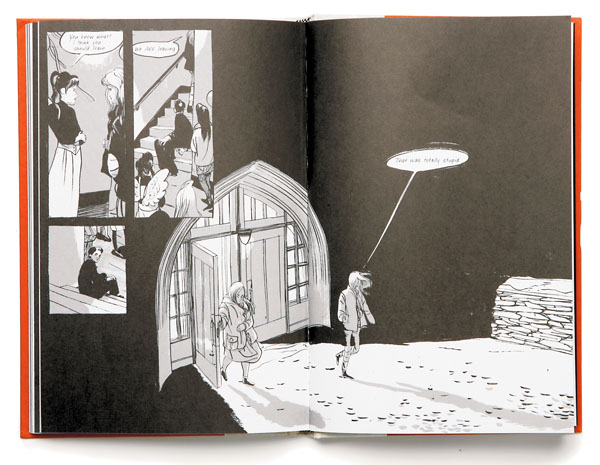

Forgive me– as if to make this piece as dilettantish as possible, I am going to bring film into a discussion of comics and music.

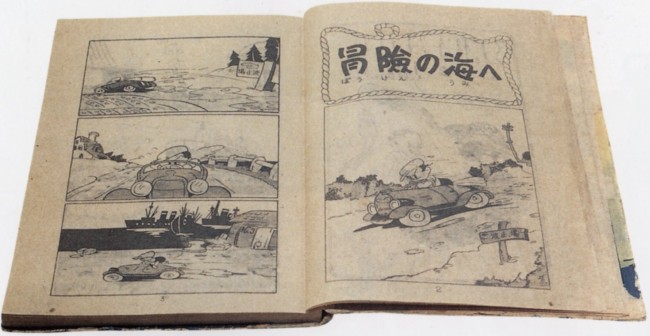

The first pages of New Treasure Island by Sakai Shichima and Tezuka Osamu, much praised for its cinematic quality

It’s seems to me that when a comic’s flow of panels and pages works ‘musically,’ it also behaves cinematically. The artist’s shifting of perspective and the rhythm of the ‘cuts’ echo filmic sequences that are usually accompanied by a score. Sometimes, when I come across these sequences, it feels like phantom music– like a phantom limb– underscores the comic. It’s a struggle to read along to, or to figure out how the melody goes. Going back to re-read or dwelling on an image too long disrupts the phantom score irrevocably, and forfeits some of the emotional impact of reading the comic. As a teenager, I tried unsuccessfully to hum along or deejay background music while I read comics, hoping to discover total emotional absorption.

Today I better appreciate comic’s more complicated relationship with time and space. I believe I was stupidly hoping to watch– or listen– to comics as opposed to reading them. I wanted to be passively taken in, when I had to stake my own way through a comic book. If watching a film is like having a dream, reading comics is like lucidly dreaming– there’s an exchange of vibrancy and intensity for control and self-awareness.

Cinematic pacing still confuses me. It’s found a natural home in many comics, yet it is a very anti-Greenbergian hold-over from another medium. Cinematic pacing does not accentuate the qualities that are most fundamental to comics, and instead channels comics’ unique handling of time, space and design into straightforward, uncomplicated narrativity. That’s not to say some overlap hasn’t occurred– cartoonists often work as storyboard artists. I don’t think cinematic pacing should be avoided, or that it poses a threat to ‘native’ comic pacing. But I do feel that the relationship of comics and film is worth examining, especially as the value of comics is increasingly understood in terms of their adaptation into film– where the story is finally told with real-life music.

I’ll clarify what I mean by cinematic comics. Comics are cinematic when they follow established film and cinematographic formulas of conveying time and space in a dramatic, rhythmic, and unambiguously linear fashion. I am also tempted to add ‘decompressed,’ yet some film conventions are highly compressed, (montages without establishing shots, for example.)

Not all films follow the same cinematographic formulas, and the great ones complicate or invent them. Some formulas are grammatical, like how a bird’s eye view/pan/combination is used to introduce a story, as in American Beauty or Blade Runner. An easily identifiable variation, like Citizen Kane’s No Trespassing sign, is copied intentionally through homages and parodies, and if it becomes prevalent enough, it’s recycled unintentionally. Another example are the fantasy battleground scenes that flooded theaters after the run of Lord of the Rings. These formulas are most often accompanied by music to heighten the emotional effect, and the style of the music is included in the formula.

There are many stirring music-less film sequences, yet the connection between music and emotion in narrative is pretty well established, (and necessarily predates the term melo-drama.) To keep things as simply and as overly-generalized as possible, I will vaguely refer to commercial moviemaking scores from the last fifty or so years– think John Williams, Thoman Newman, Elmer Burnstein, Joe Hisaishi and Howard Shore.

Cinematic comics isn’t a discreet category as much as a collection of traits. Very cinematic comics will more frequently carry more of these traits. Panel proportions offer one example. A panel’s size usually determines the time a reader will stare at it. In cinematic sequences, the panel size will echo the legnth of a cut. Smaller panels dispaly a smaller fraction of time, which is not always the case in comics where the page’s design, or other criteria, are more important than the linearity or pacing of the reading. Small-size, low-content panels allow the eye to ‘bounce’ across the gutter, like a script’s ‘beat,’ without twisting the amount of time the panel naturally represents.

Non Cinematic– Panel size determined by design, not by the length of the time it represents. From Adam Hine’s Duncan the Wonder Dog: Show One

Non Cinematic– The third panel is small, but designed to be dwelled upon for some time. From Invisible Hinge by Jim Woodring

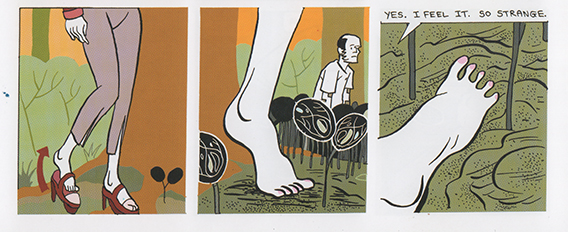

Cinematic — Panels represent one cut, and small wordless panels work like ‘beats’

From Bodyworld, by Dash Shaw

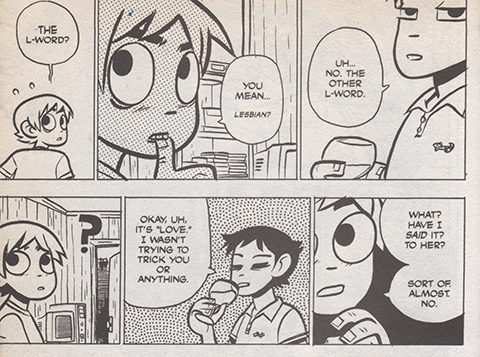

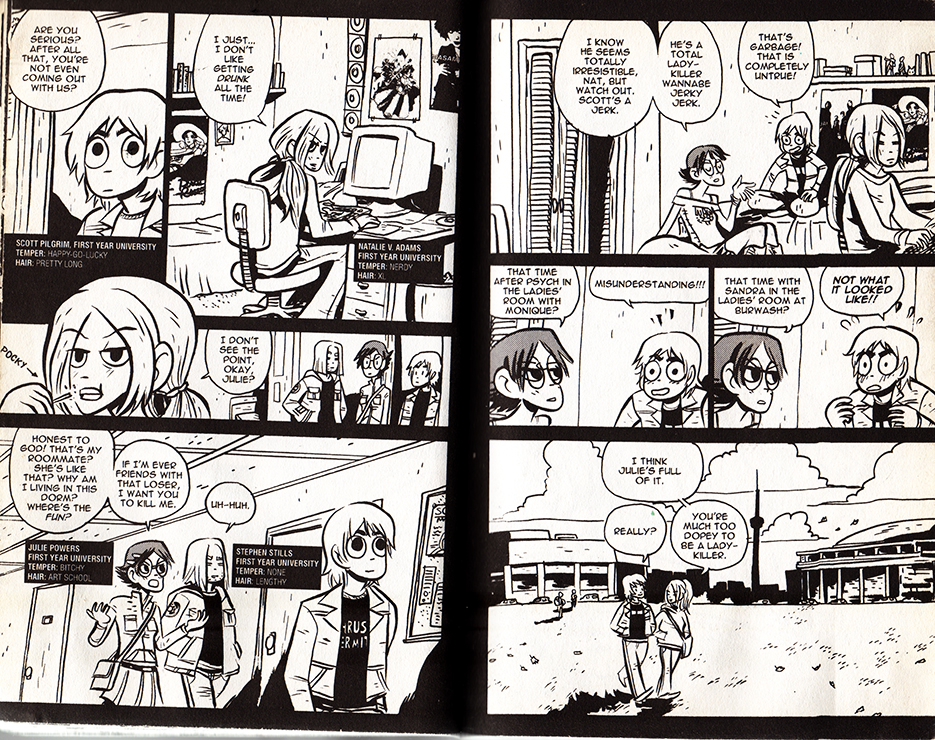

Cinematic — Panels represent one cut, the size suggests the length of time represented, and small wordless panels work like ‘beats’ From Scott Pilgrim Gets It Together by Bryan Lee O’Malley

In a cinematic comic, a panel’s text to image ratio is usually small, and corresponds to how much dialogue belongs inside one ‘cut,’ or between moments of physical acting. Reading the panel aloud, this is often under thirty seconds. A preponderance of textless panels showcase ‘beats’ of the character’s wordless performances, and occasionally more panographic panels and splash pages demonstrate setting or spectacle. These are sometimes an exception to the rule: splash panels and pages can be three to twelve times larger than an average panel, yet unless there is text they don’t necessarily take that much longer to read. Nevertheless, the moment depicted is mentally understood to last longer, and that it eludes to a build-up and follow-through that wasn’t drawn. Larger, more detailed panels with multiple speech bubbles work like a ‘pan,’ where the camera scrolls across a larger field of vision.

The cartoonist’s perspective choices share commercial filmmaking’s desire for clear communication. If the character is about to step on a rake, a successful cartoonist will most often show the ‘build-up’ and ‘event’(approaching and stepping on the rake,) within the larger environment, and only afterwards show a close-up of the character’s reaction, etc.

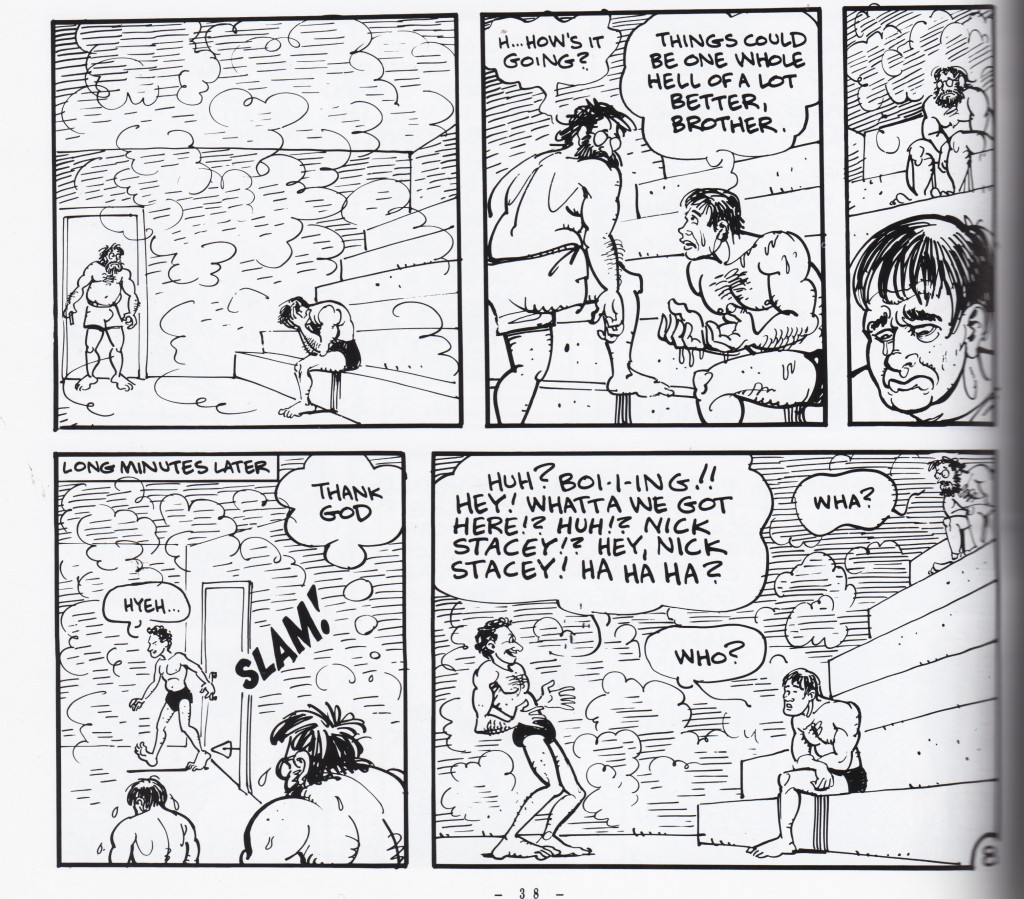

The cinematic comic’s cuts are determined largely by dialogue, and by fight-scene and slapstick choreography, and when there is neither, by the comic’s internal rhythm. In film, this rhythm is determined by the score, which needs to match, the pacing of the talking/fighting/comedy scenes as well. As long as the cartoonist obeys cinematic conventions, the more rigorously rhythmic the pacing, the more strongly a phantom score can adhere to it.

Certain comics rhythms/formulas recall certain filmic rhythms/formulas, and by association, inadvertently acquire phantom film scores. Cartoonists are a little helpless– while a filmmaker could pick an iconic or untraditional song to accompany a sequence, a cinematic comic only triggers a super-conventional-hodgepodge-memory of what song ‘should’ go there. Friends hanging out on a summer afternoon demands calls for a low-key, chirpy groove. A troop’s noble suicide mission demands the Lord of the Rings bombast. A sad remembrance cues violins. And if the comic’s pacing is cinematic enough to strongly suggest a score, its absence is distracting. The tingling of a phantom limb is most often painful.

In conclusion, a meandering examination of some cinematic comics:

Scott Pilgrim!

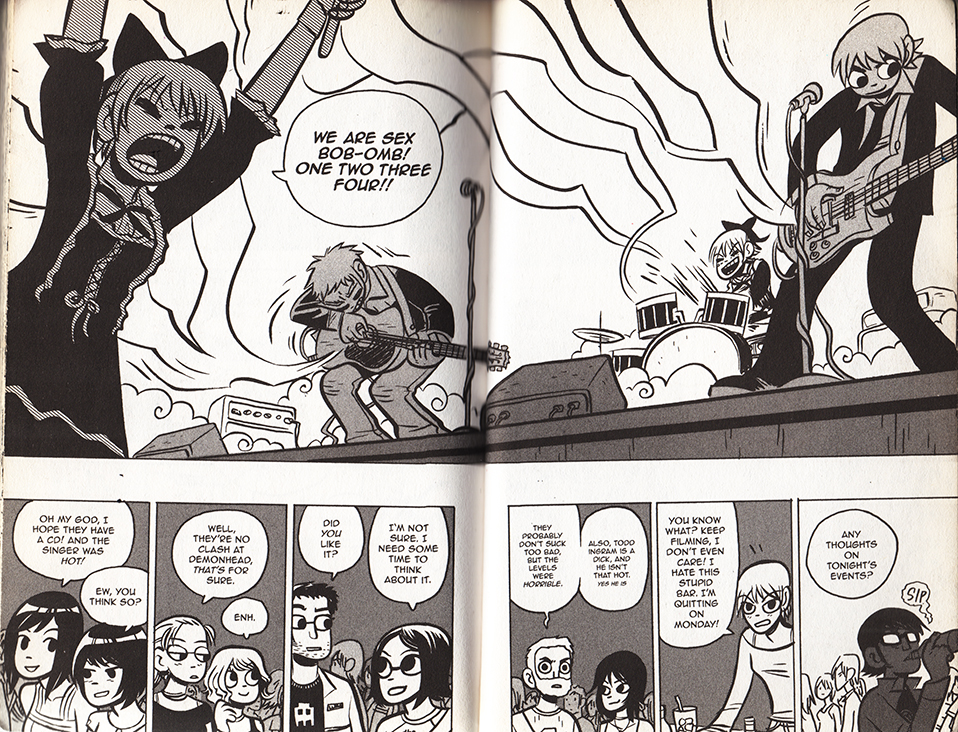

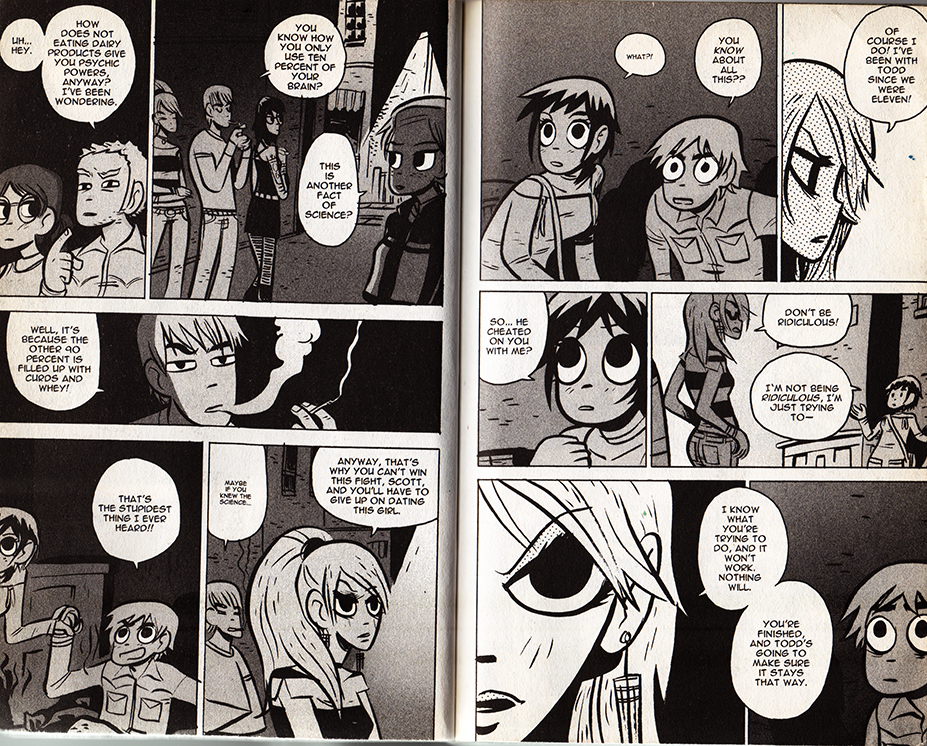

Music plays an even larger role in videogames than it does in film. And when I think of a ‘cinematically paced’ comic, Bryan Lee O’Malley’s videogame-infused Scott Pilgrim series immediately comes to mind. Coincidentally, the characters play, discuss and listen to a lot of music. What does Sex Bob-omb sound like?

The books toggle with several cinematic genres and conventions. O’Malley showcases a playful mastery of anime and martial-arts cinematoraphic formulas. At two points the comic frames itself with a few vox pops, but I guess that could be as much of a homage to Dan Clowe’s Deathray as Boondock Saints or Monty Python’s Flying Circus.

Most impressively, Scott Pilgrim uses hyper-condensed styles of cinematic storytelling, as when a whole relationship is traced over a series of pages. As long as filmmakers establish iconic characters and settings, audiences can easily follow a scattered montage. In comics, the specificity of the background often sacrifices the clarity of the characters, and a drawn interpretations of places are often unfamiliar and stylized. It’s a testament to O’Malley’s craft that this scene (below) is so effortless to follow. O’Malley uses this technique at several points in the series– pointedly never for athletic training ala Rocky, but always for relationships.

From Scott Pilgrim Versus The Infinite Sadness

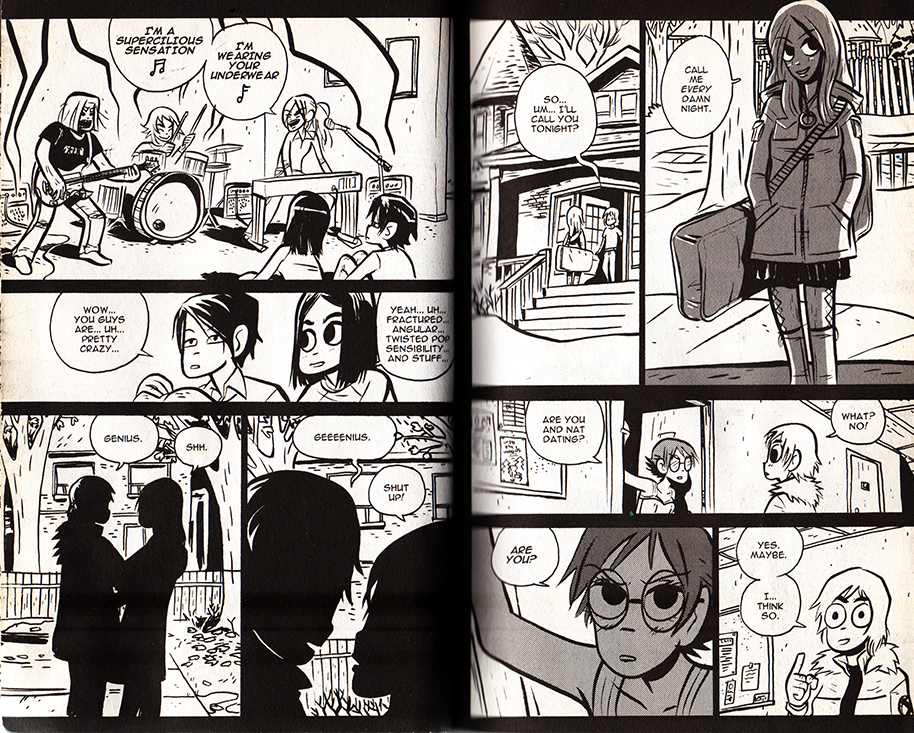

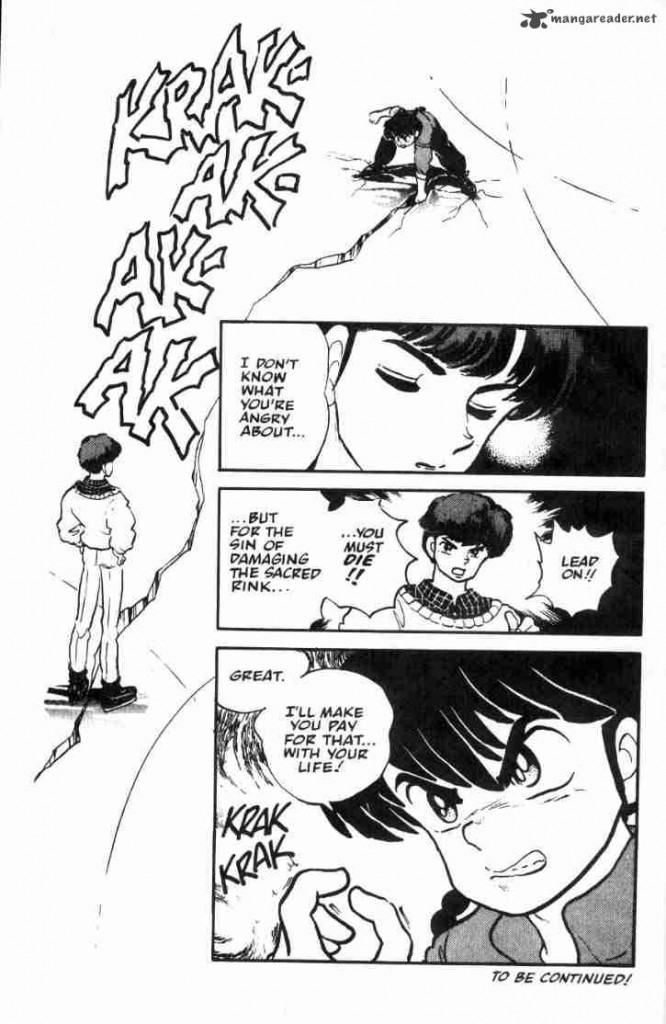

Reading comics, I’ve often felt that manga reads more cinematically than American comics, because of the smaller text to panel ratio. I don’t have any hard evidence for this, but manga is thought to be a major influence on the development of decompressed and widescreen comics.

Read Right to Left:

From Rumiko Takahashi’s Ranma 1/2: Volume 3

From Daisuke Igarashi’s Children of the Sea #8

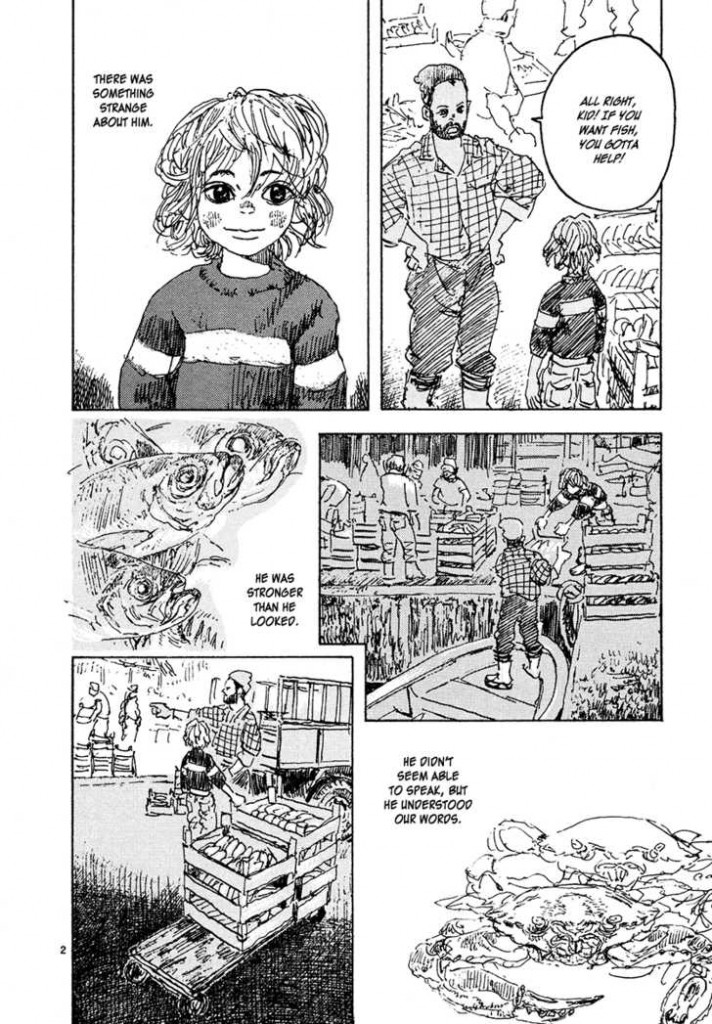

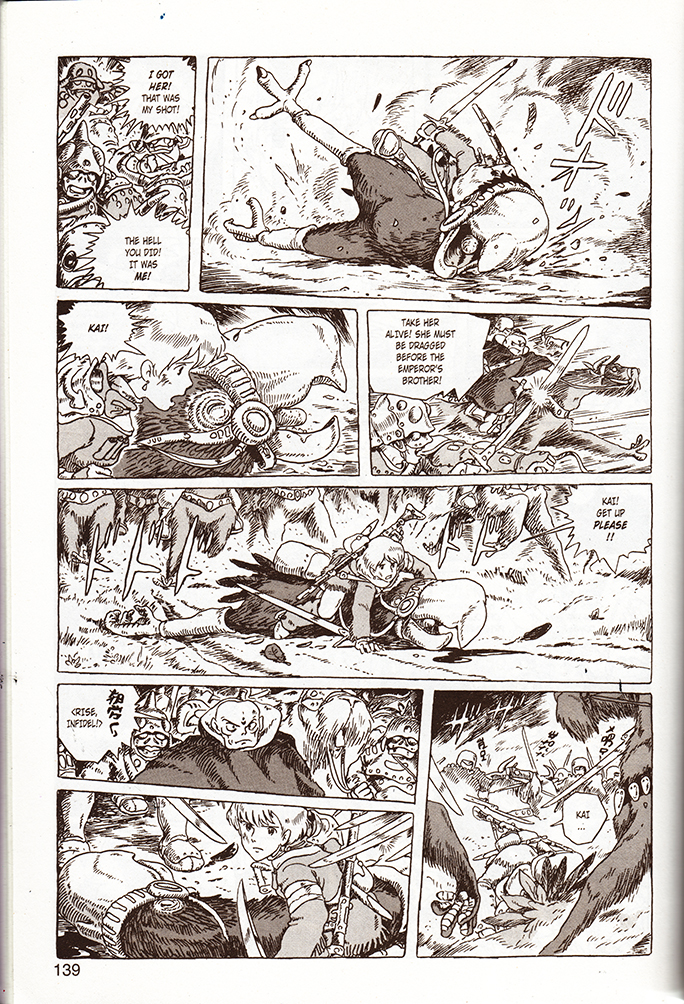

Akira, (the quintessential decompressed comic,) and Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind are slightly higher brow (and arguably Westernized) examples, and coincidentally are better known for their film adaptations. As comics, both read like gorgeously realized, meticulous storyboards. Reading Nausicaa, I found myself mentally humming pieces of classic Hollywood war and western scores, and occasionally, (appropriately,) a little Hisashi. Yet I’ve never seen the film adaptation with his score.

Read Right to Left:

From Nausicaa of The Valley of the Wind, Book 3

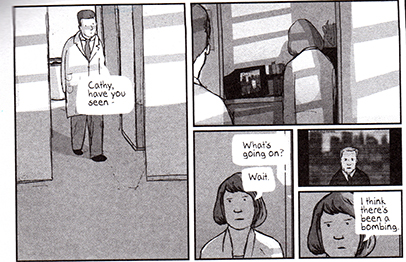

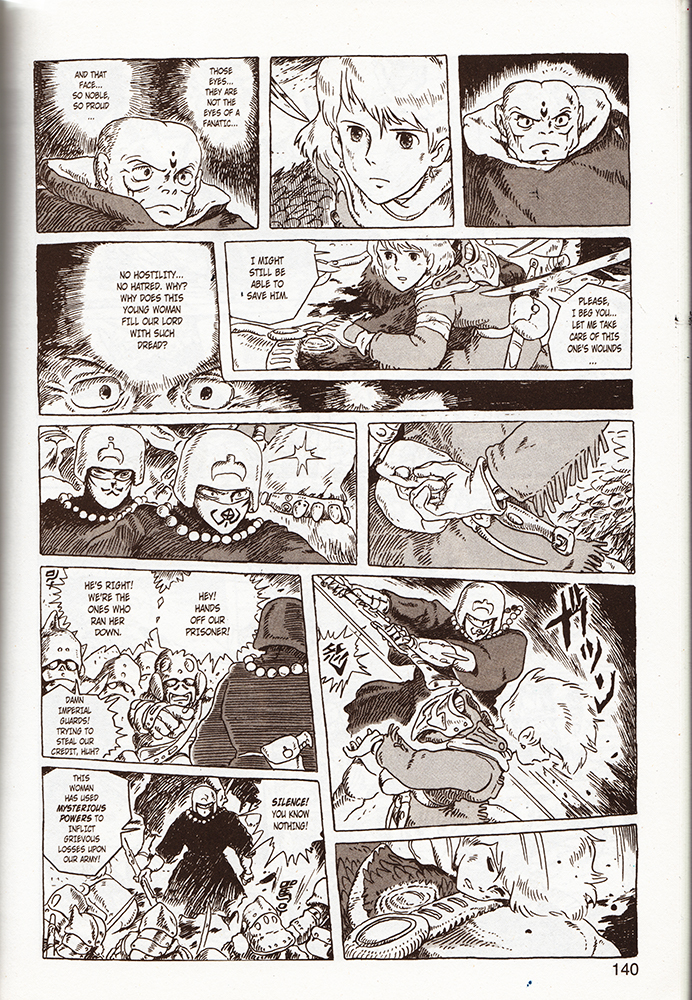

I’ve written a bit about the cinematic quality of Jason Lute’s Berlin: City of Stones here. Lutes comes as close as Miyazaki to making a ‘movie in a book.’ He doesn’t push the boundaries of comics narrativity, and focuses on virtuosically recreating the mis en scene, pacing, and character management of films like Wings of Desire. I’ve complained that Berlin’s ironies alienate readers from the characters, and perhaps a little background music could have sweetened the deal.

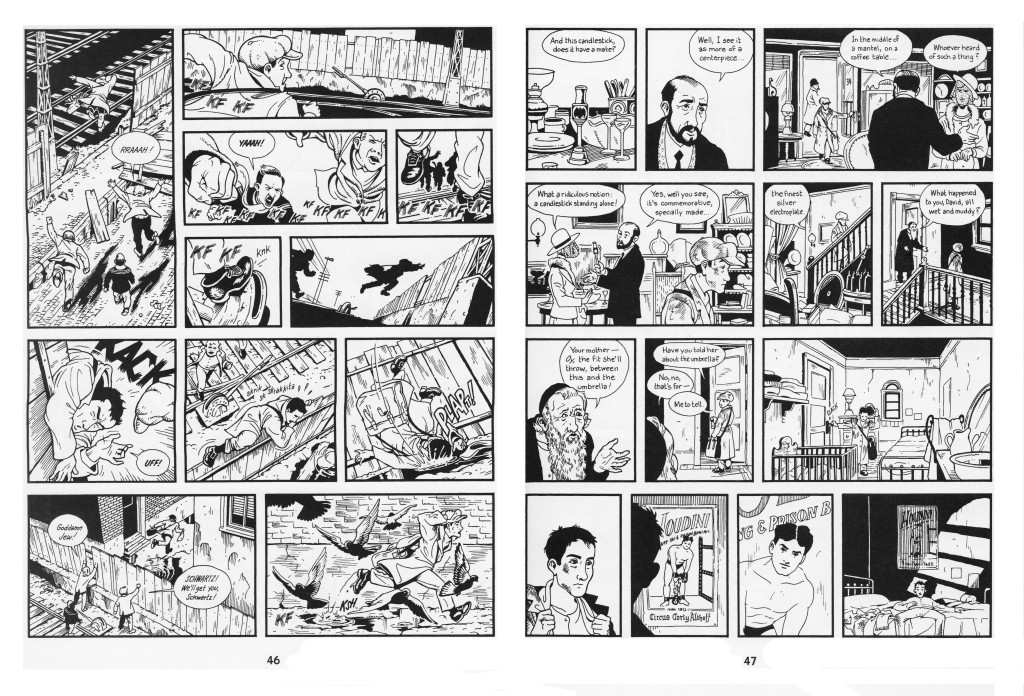

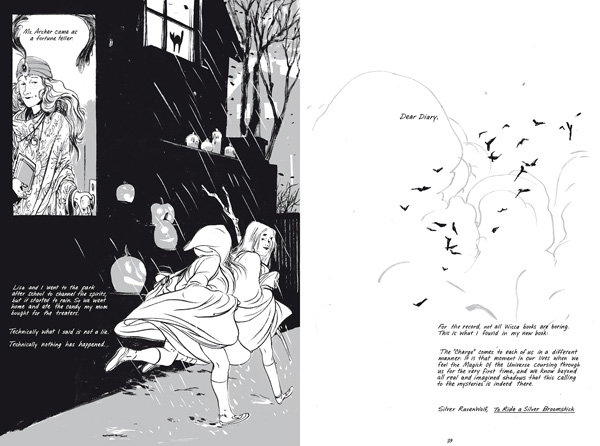

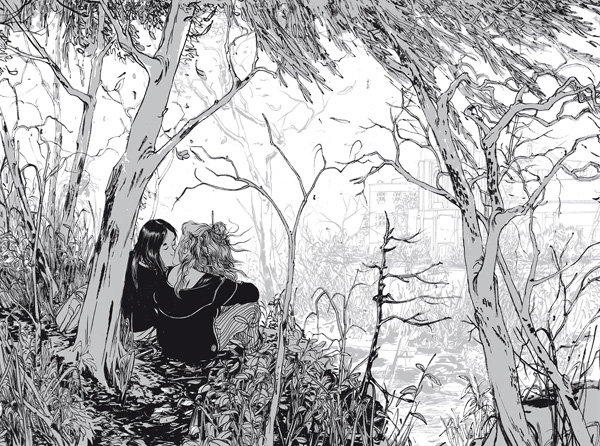

Skim by Jillian and Mariko Tamaki is an intersting example. While sometimes (unintentionally) dismissed as a teen comic, it is temperamentally aligned with the quieter side of Hollywood epics- adult coming-of-age dramas like American Beauty, The Shawshank Redemption, A River Runs Through It, and The Cider House Rules, (which are often literary adaptations.) The wikipedia page for The Shawshank Redepemtion contains a great note on Thomas Newman’s score:

…the main theme (“End Titles” on the soundtrack album) is perhaps best known to modern audiences as the inspirational sounding music from many movie trailers dealing with inspirational, dramatic, or romantic films in much the same way that James Horner’s driving music from the end of Aliens is used in many movie trailers for action films.

“End Titles” is probably a good candidate for Skim’s phantom score. Unfortunately, this makes Skim sound heavy-handed, and I’m relieved that “End Titles” doesn’t accompany the book’s heartbreaking, graceful layering of voice and images. Not to say that they don’t sometimes suggest it.

The following pages are in sequence:

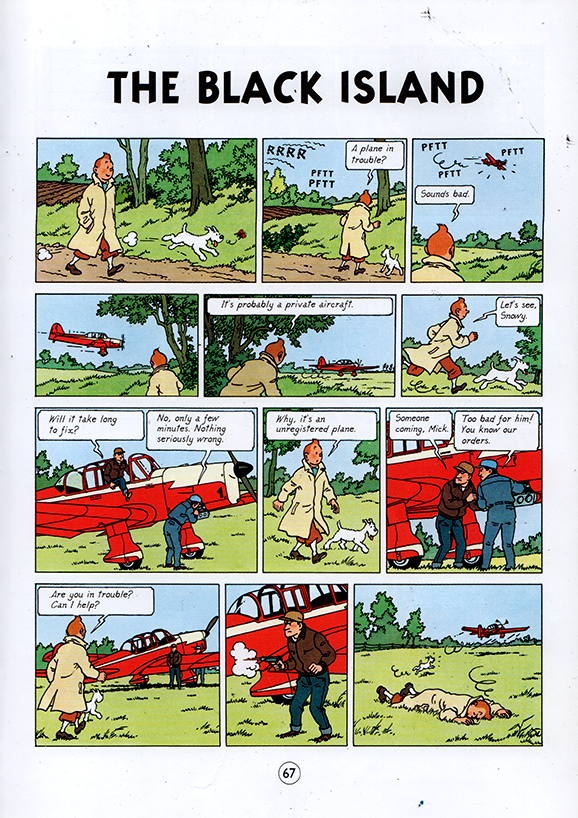

Comics like Tintin are a little more complicated. Herge’s ligne clair extends to the pacing of the comic, and complicated action sequences are detailed moment by moment, like key frames in a storyboard. Yet Herge is so ungratuitous that when he get’s the chance to skip a few key frames, he does.

From TinTin: The Black Island

The phantom score between the last two panels experiences skips like a warped record. Otherwise, I’m not sure why I don’t find Tintin very cinematic– I guess I want to blame the page size. You can pack a lot of panels and text onto an album page, as opposed to the small leaves of most manga books. By the virtue of their size, manga pages automatically resemble dramatic splash pages, and the act of constantly turning pages creates a breathless momentum that exaggerates the cinematic pacing. Tintin is literally less of a page turner.

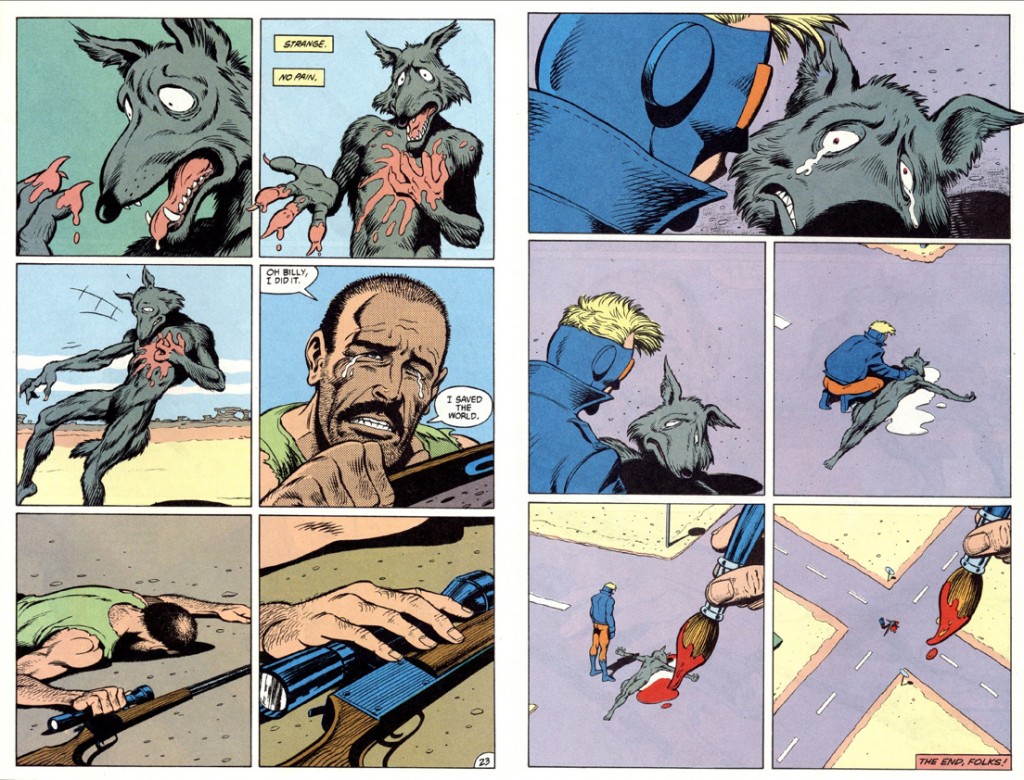

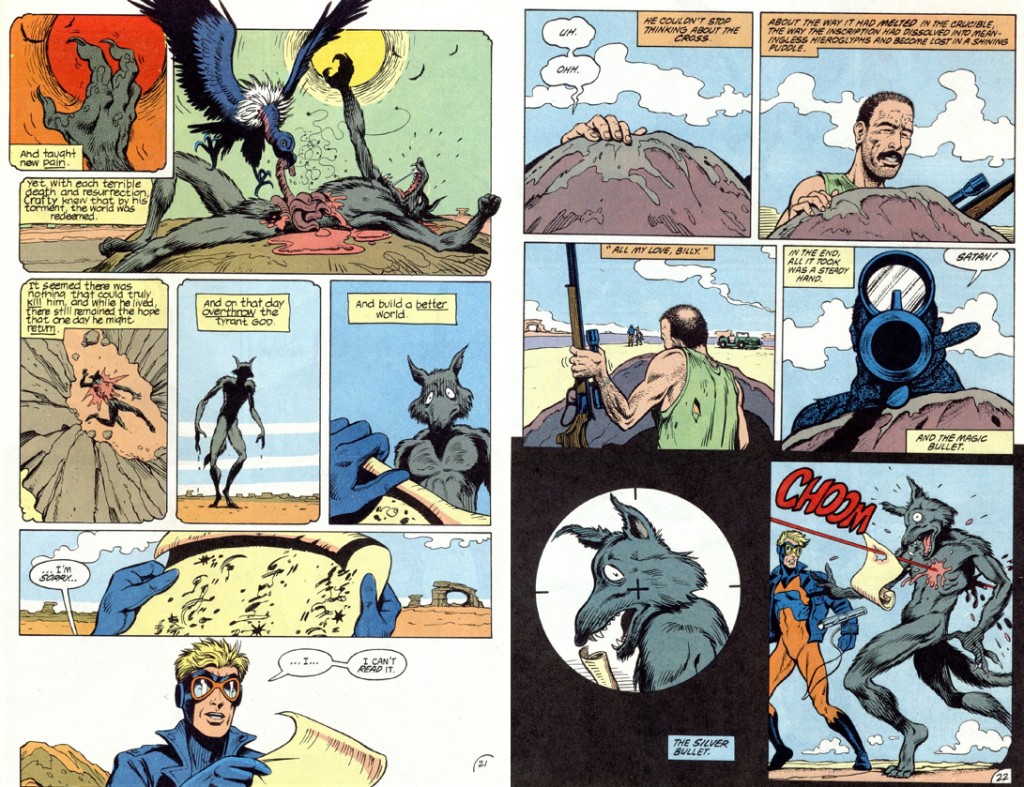

from Morrison, Truog, Hazelwood, Costanza and Wood’s Animal Man #5

My piece is sorely missing examples from mainstream superhero comics. I’ve spent hundreds of hours scanning, assembling and digitally correcting them at Marvel, and have read a decent amount of them myself… but I don’t own any, and I don’t consider myself well-read in them. I’ve enjoyed Alan Moore and Grant Morrison’s work, but I get the feeling that they encourage cinematic pacing more often than other writers. I remember putting pages together on a stunning Hulk comic– it was printed sometime in the fall of 2009, and it opened with panel after panel of the Hulk charging at the viewer in darkness. When I saw the finished book, the whole thing had been slathered with first person captions. I couldn’t bear to keep it. Perhaps I’m being unfair; heavy-handed voice-over is also cinematic in its own special way.

I have to say, many of my favorite comics use panel size to create rhythm/pacing; I like it a lot and I don’t see anything wrong with it. I don’t really see it as anything “cinematic” either – to me, it could just as well be seen as the visual equivalent of creating rhythm in a novel by varying the sentence (or paragraph) length. I’m not even sure what, exactly, you’re opposed to – do you want comics that feel less dramatic, where panels can be read in any order, or what?

I don’t think Kailyn’s saying there *shouldn’t* be comes like that. More pointing out that they’re very prevalent, and that there are other ways to go?

I’d agree, incidentally, Kailyn, that Moore is extremely cinematic…and I think influential as well. Morrison too…though his handle on the effects often seems shakier….(and of course the approach of their collaborators matter as well….)

HI Martin– I don’t think that using panel size to create rhythm and pacing is exclusive to cinematic comics, only that there are certain trends that resemble common cinematographic formulas. I think many cartoonists use panel size to create rhythms and pacing that are less common, or unattainable, in film as well. Adam Hine’s and Allison Bechdel’s work are good examples.

I also don’t believe that cinematic pacing is a bad thing– I’m not very Greenbergian when it comes to comics. I just think that the relationship of film and comics is worth studying, especially when comics are used as a way to realize (or develop) ‘filmic’ visions and concepts. A few years ago, I would have argued that cinematic comics are better, because they are more emotionally absorptive, although I don’t believe this anymore.

Noah– I think you’re right about Morrison, and I think the selection I used from Animal Man is from an uncommonly cinematic issue. (But does that have any connection to why it’s so treasured by fans?) I need to read more of Morrisson’s work– I wish I had a better handling of it.

Thank you both for reading!

There are some cartoonists who very overtly try to replicate the rhythm and other effects of music in their layouts.

I’d cite Jim Starlin and Guido Crepax in the lot. Starlin is particularly clever in rhyming images or creating leitmotiven.

Animal Man #5 is a very cinematic issue…. It’s also maybe the best thing Morrison’s ever done. I’m not sure quite how those two things go together. I don’t think it’s “cinematic comics are always better.” Maybe more like Morrison always seems to struggle with visuals. Latching onto cinema (either in his script or because the artists did so, or maybe both) perhaps gave him a stronger visual way to put together his comic than he usually manages.

As a side note, I was intrigued to read that you’d read Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind but hadn’t seen the movie. If you ever get around to seeing it, I’d be curious to read your thoughts, coming from that perspective. I came to the comics long after I’d seen the movie, though I’d seen some of the chapters when they ran in ANIMAGE. It’s often incorrectly stated that the movie is an adaptation of the first few chapters of the comic, but this is only partly true. The movie version is considerably simplified, with several important characters and entire groups/nations omitted (e.g. the Doroks) and the sequence of events is different in some cases. Princess Kushana is quite different in the two versions both visually and in terms of actions/motivations. Kurotowa is also somewhat different, and despite being a complete jerk in both versions, is probably my favorite character in the comic book version.

AB– I’m really intrigued about Starlin and Crepax. I’ll see if I can pick up some of their work soon. Thanks for the tip.

Noah– I agree… I like his decompressed work best, because the visuals finally match the kind of impact he’s going for in the script.

Daniel– I would love to have someone to discuss Nausicaa with! I’ve had the books on my shelf since I was a little kid, but found them impenetrable until I picked up larger former copies at the library this winter. (The problem now is I’m facing the ‘last issue hold-up’– its always a really really long wait for the final issue, no matter how old the series is, for some reason.) I think I missed a recent film screening of Nausicaa though– shoot!

I am so happy to hear about another Kurotawa fan! He’s my favorite too. He accounts for so much of the human interest of the story. I love that moment where he’s summoned by Kushana, and as he steps into her chamber, he briefly thinks “It smells nice.” Or maybe its “She smells nice.”

Yeah Nausicaa is one of the best examples of a comic book that should never have been reduced in size. The large ANIMAGE formatted pages were larger than most Japanese comics pages, even in the weekly “phonebooks”.

Kurotowa is totally believable and makes for a nice contrast with Saint Nausicaa. My favorite of his scenes is when he takes control of one of the airplanes mid-battle with words to the effect of “this might get a little rough!”.

Hey Noah, how about a Nausicaa discussion to avoid hijacking this thread?

Ooh! I volunteer to write something for that!

It’s not just Kurotowa’s foil to Nausicaa… their relationship is wonderful too. Nausicaa is a pretty distant, too-perfect character, and I think we mediate our relationship to her through the other characters. Kurotowa is simultaneously very fiesty and very analytical, and Miyazaki explicitly illustrates Kurotowa’s constantly shifting attitude toward Nausicaa through his expressions and internal monologue. This in turn mirrors our uneasiness with her. Miyazaki masterfully makes this analysis entertaining, and its very rewarding to see how Kurotowa’s (and our) relationship with Nausicaa evolves.

I think Miyazaki creates structurally perfect narratives. He’s very comfortable with ‘the edge of the world,’ trope, which he locates at the beginning of the end of his stories. I think Kurotowa’s inclusion in Nausicaa’s edge of the world, (when Nausicaa returns from her extended dream-state,) was a perfect and very meaningful choice.

No worries; feel free to talk about Nausicaa here! I don’t mind thread hijacking as long as it’s tangentially related and not trolling….

Okay, I’m game. I’d been thinking recently about doing a full re-read, so this might be a perfect excuse.

Another favorite Kurotowa moment from the comic book: he starts to give a rousing, don’t-let-his-death-be-in-vain speech after a soldier seems to have died, only to be interrupted by Nausicaa telling him that the guy’s going to make it! The expression on his face is priceless.

BTW, the fact that Kurotowa is “played” by the same character design (a la Tezuka’s “repertory company” approach) that was used for Count Cagliostro in the Lupin III film Castle of Cagliostro is quite intriguing, to say the least. More on this later.

Noah once commented that Dan Clowes thinks he’s Luis Bunuel. That cracks me up because it’s true.

I would rather say David Lynch.

Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron certainly had a Lynch-y vibe, but with a lot less violence against women.

Bert, I hear he’s done a book or two since Velvet Glove.

“Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron certainly had a Lynch-y vibe, but with a lot less violence against women.”

Are you sure? The heart of the protagonist’s quest is a missing woman, who turns out to be murdered.

Well, I did say “less violence against women”, not “no violence against women”.

But seriously, it’s been a while since I last read LAVGCII or watched any David Lynch, but in the case of the former, that aspect of things didn’t seem as dominant as it did in the last few Lynch projects I bothered to watch. I was a big a fan of Twin Peaks in its television run, but I gave up on it and him after Fire, Walk With Me to be honest, primarily for that reason. With the exception of the wonderful time travel scene featuring David Bowie, all of the oddball humor and visual inventiveness that had initially attracted me to the show was gone, and in its place was just one awful scene after another of women being threatened, beaten, raped and killed.

I love Fire Walk With Me. I absolutely get not wanting to watch depictions of rape, incest, and violence. I disagree with what I take to be your implication, which is that focusing on those issues is necessarily about identifying with the violence.

Women are actually threatened, beaten, raped, and killed, and incest really is hyperbolically horrible. I don’t think it’s wrong to point those things out.

I actually have a whole chapter in my Wonder Woman book about this issu. Maybe it will come out some day….

For me it’s not about identifying with the violence so much as the highly aestheticized way that the violence is presented and the fact that the movie, despite its nods to the show’s continuity/plotlines seemed to be primarily concerned with depicting that violence rather than exploring more of the Twin Peaks universe. I’d have gladly traded a slow-mo Killer Bob tongue scene or two for Major Briggs talking about his dreams/visions or something like that. The Bowie time travel riff I mentioned was exactly the sort of thing I mean. It came across as somehow both funny and sinister and suggested an intriguing plot development, but it was never mentioned again. Even the incest angle wasn’t really explored as much as it was in the TV show, where Leland’s actions were presented as a consequence of his own abuse by Bob rather than simply as an excuse for yet another lurid depiction of Laura being brutalized. It’s true that in the real world, women really are brutalized in this way, but somehow the TV show seemed to handle it a lot better (IMO); furthermore, that was only one aspect of the show and while it was important, there were a lot of other things going on as well, whereas in the movie it seemed to be the main focus.

What did you love about the movie exactly?

It’s like what’s done with Alan Moore: Blue Velvet, Inland Empire, Twin Peaks, Mulholland Drive and Lost Highway all feature major women characters who are subjected to violence. Thus, Lynch has been called a misogynist.

Man, Daniel, the fact that Lynch creates horrific tension in the broad daylight at a trailer park is pretty amazing, too. I love the whole prologue with Isaak and Sutherland (“who’s the toehead?”).

I think the film is one of the most terrifying depictions of familial violence outside of a documentary like Capturing the Friedmans, which made me nauseous. Which, granted, this is the problem that anti-violence types always have with its use in entertainment: the violence is part spectacle, regardless of whatever moral content or aesthetic worth the film might have. That’s why I can repeatedly watch Fire Walk with Me, but not the aforesaid doc. I’d suggest another way of saying this is that the violence is fictional (but that doesn’t quite have the ring of post-marxian moral condemnation to it).

The violence against women/misogyny theme in Alan Moore’s comics has been something of a stumbling block for me in recent years as well. Again, perhaps he would argue that he’s simply depicting the world as it actually is, but I’m not convinced. The fact that the Watchmen movie picked up on this and amplified it is one of the many things I hated about that movie.

I recently revisited Halo Jones and was struck by how negatively he portrays many of the women in it, which is very odd for a series that he claims was done as an attempt to do a kind of Love and Rockets ripoff/homage. More recent stuff isn’t much better: Promethea, despite his best attempts, seems incredibly clumsy and misguided in its depiction of women, even strong women. To his credit, he does a lot better (IMO) in Tom Strong, but for lady superheroes I’d rather read Whoa Nellie! or God and Science any day.

Fire Walk With Me is fun for the first 20- 25 minutes, before it gets to the Laura Palmer stuff. It’s a pretty much universally reviled movie, is my understanding, and lacks the charms of the TV show past the first 20- 25 minutes.

If it added anything interesting to what we knew of the back-story of Laura Palmer from the TV show, i certainly missed it. (it does have a nice bit that hints how Cooper will escape the Lodge, though. Laura is told to write in her diary that Cooper is still trapped in the Lodge).

Charles – I agree. That was a good scene. Basically, the 10 minutes (or so) with Cooper (which includes the Bowie bit) are as good as the movie gets for me. And those scenes are indeed very good, putting me right back in the zone that the TV show did.

I wrote about Fire Walk With Me here. I don’t know that that review gets at what I like about it though…. It’s very different from Twin Peaks, definitely. Twin Peaks is funny and odd; it uses the detective genre as a kind of formalist entertaining riff — which is awesome. Fire Walk With Me, though, is more about the underlying violence that the detective genre domesticates. And yeah…as Charles says, it’s just a harrowing depiction of incest and violence. Understanding that Leland is a victim is worthwhile too…but Fire Walk With Me is about what it feels like to be on the receiving end of that kind of terror. It uses horror to empathize with the powerless. I find it really moving and disturbing.

Alan Moore is a little trickier. I think a lot of his depiction of violence against women is feminist; that is, in the interest of honoring women’s experiences and condemning their oppression. But he’s also really tied into the pleasures of genre, and soemtimes those kind of get away from him a bit.

Halo Jones does pretty interesting things with gender, and has lots of female characters. And Halo’s genocidal general friend is a (self-) parodic vision of masculinity…I dunno. Showing some women as not being ideal doesn’t seem misogynist to me — though, again, not that Alan Moore is incapable of misogyny at all times.

It’s not generally a favorite among Lynch nuts (or anyone else), I guess. I like that he turns the whole series into a circle with the movie while giving Laura a release. In the TV show, she’s either a body or a manipulative bitch. The movie fleshes out her character a whole lot more, which adds gravitas to the show. (That ceiling fan becomes a whole lot more terrifying.) I’m pretty sure that Lynch wanted to use the film as a corrective to her story, since ABC forced the resolution of her murder (they “killed the golden goose” is how he put it). I mean, the writers couldn’t really delve any more into her character in flashbacks once her murder was resolved.

Most people hated the movie for not carrying on the story in a linear fashion, which was a disappointment for me, too, when I first watched it.

I saw the film before the show, so no disappointment for me.

That’s certainly an interesting perspective! I watched every episode of the show during its original run, watched the European feature film version when that became available, read The Secret Diary of Laura Palmer when that appeared and saw FWWM the weekend it opened. I also saw Wild At Heart during its theatrical run, which doesn’t really matter of course, but at the time that movie almost felt like an extension of the series to me, though that may have just been wishful thinking on my part due to my disappointment that Lynch seemed to kind of abandon the first season half way through to work on WAH.

Pretty much all my favorite episodes of the show were the Lynch-directed ones, though I recall a couple of the Mark Frost episodes being rather good as well. I’ve often speculated that what was missing from FWWM was whatever angle Mark Frost brought to the table. Though I loved the final episode, I still think the show, much like The Prisoner went on far too long (despite the latter only having 17 episodes!). I’d have been much happier if TP has run about 12 episodes total and I think one could easily edit the existing material down to that length and lose nothing. I hated all the Windom Earle stuff, but I’ll confess that I found the subplot with Andy and the demonic child kind of amusing, though it felt almost like a spin-off within the show.

Yeah. Contra Charles, Fire Walk With Me may be one of my favorite films. Certainly my favorite Lynch film, though I quite like some of his others.

I should watch it again and write about it. We’ll see….

I think part of it is that I’m really a sucker for feminist horror films.

Well, I also love FWWM. It’s one of my favorite Lynch movies, and I do think it’s better than the series, which I re-watched semi-recently.

The reason is because it’s really about violence. In my movies (or comics) I don’t like violence to be either immoral (and thus usually a justification for more violence) or amoral (it’s fun! lighten up!), but exciting and horrific– the abyss of power and pleasure that never stops feeding itself.

As I kid I was always fascinated by the disconnect in comic panels where the action depicted (Spidey kicking a hood) was clearly no more than a second or two, but the wisecrack Spidey spat out had to’ve taken at least six seconds. That kind of weird, wobbly pacing can’t exist in film.

I’ve never had that synesthesia with comics and non-existent music… it’s a bit like how Donald Duck, in comics, doesn’t speak with that familiar voice in my inner ear.

I love FWWM and the show in different ways. I’m one of the many who thinks the show turned into mulch after they resolved the Laura mystery; maybe one reason the film excluded all the cheerful small town fanservice was that by the end that’s all the show was; fashion shows and beauty pageants, with all the intended tension coming from goonybird bric-a-brac that missed the genuinely eccentric texture of the early episodes. The movie was a staunch corrective to the wispy decline of the show.

Bowie’s album Outside is a concept item with strong Twin Peaks correlations. A girl is murdered; a cast of eccentrics may or may not know why; there’s no narrative resolution. The story in the CD Booklet is part and parcel of the concept, so I don’t recommend just downloading the tunes.

Pretty fascinating essay, Kailyn! So “meaty” I’m going to have to return later and masticate some more.

Re that side issue; the thing about creators regularly featuring violence against women, are they…

– Showing women as conniving vermin who deserve such treatment?

– Depicting it as glamorized, aestheticized, sexy?

– Exploiting the fact that audiences consider violence against women as more heinous, hence featuring it is an easy way to get a reaction from the audience? (Thus, the whole “damsel in distress” tropes.)

– Feminists showing violence against women to dramatize how terribly women get treated? (And, no matter how vile and brutal they show the act, still get accused of exploitation…)

Surely the approach, and possible reasons for it, ought to be weighed when apportioning the moral condemnation…

I love the film, Noah, but not when I first saw it. I put FWWM number 3 in my ranking of Lynch films, and I’d still hold to that.

Aaron– Yeah, that wonkiness is something I originally didn’t appreciate in comics, but I’m coming more and more to enjoy it. I wonder if comics pacing can be more reflective of mental activity than film– like a sensory homunculus. It takes longer to process dialogue, so we accord it more seconds, while we only need a small momentary icon to understand someone spitting. Readers don’t need the dramatization because they get the gist. They only need the dramatization when its supposed to be a more emotionally absorbing scene.

You’re lucky you can read comics without the voices– for me its nearly impossible. I invent voices in my head for every character.

Mike– Aw, thank you! I’m looking forward to hearing your thoughts.

No time to reread yet, much less properly chew, but some thoughts to toss is:

Re this business about some comics being “cinematic” or not, it’s worth taking into account that some films are not particularly “cinematic” either; especially the early ones, which were often a matter of setting a camera down before a stage production.

Not only storyboards (which often feature arrows indicating camera or character motion), but these “Foto Novels” — featuring frame blowups of movies — are an interesting intermediary stage between comics (of the fumetti variety) and film:

Richard J. Anobile in the mid-seventies edited books of “Psycho” (“Accurate and complete reconstruction of the film in book form. 256pp. Over 1,300 frame blow-up photos shown sequentially and coupled with the complete dialogue from the original soundtrack”) and Keaton’s “The General” (“It comprises 2,100 frame blowups showing the whole of the action including all (over 200) of the title cards.”) [Descriptions from http://www.antiqbook.com/search.php?action=search&o=godley&catalog=Performing%20Arts%20-%20Film&l=fr ]

Besides Anobile’s “Psycho” book, I’ve also got a similar treatment of the first “Alien” movie, lavishly produced in full color, and others…

——————————-

It was 1974 and the videocassette recorder was, at least for home use, still on the distant horizon. If movie fans wanted to relive a favorite classic movie, they had few choices. The could wait for an art-house re-release. They could hope to catch it on late-night local TV.

Or they could buy Richard J. Anobile’s Film Classics Library.

Published by Avon and selling for the then-substantial price of $4.95, Anobile’s Film Classics Library was the closest thing to owning a copy of a favorite film that most of us fans could imagine…

——————————–

More (and some pages from the books) at http://keithroysdon.wordpress.com/2012/09/02/the-essential-geek-library-the-film-classics-library/

More sample pages and info about the books: http://frankensteinia.blogspot.com/2011/05/richard-j-anobiles-frankenstein.html

Too deliciously cheesy for words! “Classic Trek” in Foto Novels: http://bullyscomics.blogspot.com/2007/10/to-boldly-go-where-no-screen-capture.html

(Sorry, can’t stop posting URLs! More about the Foto Novels: http://www.filmscoremonthly.com/board/posts.cfm?threadID=56026&forumID=7&archive=0 )

(Pulls himself together) Now, back on this “some comics being ‘cinematic’ or not” bit:

It’s hand-painted (clearly based on film images), there are caption boxes and word balloons, yet is this — http://rue-morgue.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/HPIM0583-490×372.jpg — significantly more “comic-booky” than the Anobile version?

And for that matter, aren’t those Foto Novels — though made from scenes from the actual films/TV shows — not particularly “cinematic”?

One of the salient qualities of film is motion; of actors, actions, camera movement. These are mostly left out in the Foto Novels, though occasionally an important scene — say, the camera moving in on the bathtub drain in “Psycho” — is captured.

John J. Muth created an adaptation of Fritz Lang’s “M”; not copying film images, yet looking in many ways like the Foto Novels: http://www.vulture.com/2008/04/comics_m.html . Still, in places a bit of blur, especially in the last page reproduced, create an impression of motion.

Gene Colan’s first two pages of “Unto Us… The Sons of Satannish” superbly replicates camera movement:

http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-uX0PX4vP52w/TgSuxoeh14I/AAAAAAAAAJs/6g3c6GsjG50/s1600/doctor-strange-gene-colan-unto-us.jpg

http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-lDstzwEJzaw/TgSuzXo1jbI/AAAAAAAAAJ4/uGzPuVSIuZ4/s1600/dr-strange-gene-colan-satannish.jpg

(That last page in color: http://www.supermegamonkey.net/chronocomic/entries/scans12/DRSTR175_Opening.jpg )

(More Colan gorgeosity at http://lolafett.blogspot.com/ )

Gotta rush off to work! “To be continued”…