Dear Centre for the Study of Existential Risk,

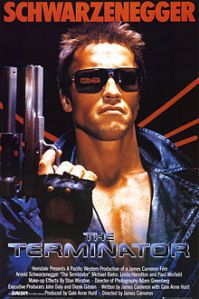

It’s rare to find folks willing to look sillier than me (an English professor who takes seriously the study of superheroes). Your hosting institution (Cambridge) dwarfs my tiny liberal arts college, and your collective degrees (Philosophy, Cosmology & Astrophysics, Theoretical Physics) and CV (dozens of books, hundreds of essays, and, oh yeah, Skype) makes me look like an under-achieving high schooler—which I was when the scifi classic The Terminator was released in 1984.

And yet it’s you, not me, taking James Cameron’s robot holocaust seriously. Or, as you urge: “stop treating intelligent machines as the stuff of science fiction, and start thinking of them as a part of the reality that we or our descendants may actually confront.”

So, to clarify, by “existential risk,” you don’t mean the soul-wrenching ennui kind. We’re talking the extinction of the human race. So Bravo. With all the press drones are getting lately, those hovering Skynet bombers don’t look so farfetched anymore.

Your website went online this winter, and to help the cause, I enlisted my book club to peruse the introductory links of articles and lectures on your “Resources & reading” page. It’s good stuff, but I think you should expand the list a bit. It’s all written from the 21st century. And yet the century you seem most aligned with is the 19th.

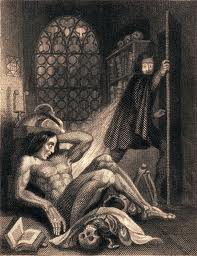

I know, barring some steampunk time travel plot, it’s unlikely the Victorians are going to invent the Matrix. But reading your admonitory essays, I sense you’ve set the controls on your own time machine in the wrong direction. It was H.G. Wells who warned in 1891 of the “Coming Beast,” “some now humble creature” that “Nature is, in unsuspected obscurity, equipping . . . with wider possibilities of appetite, endurance, or destruction, to rise in the fullness of time and sweep homo away.” Your stuff of science fiction isn’t William Gibson’s but Mary Shelley’s. The author of Frankenstein warned in 1818 that “a race of devils would be propagated upon the earth, who might make the very existence of the species of man a condition precarious and full of terror.”

Although today’s lowly machines pose no real competitive threat (it’s still easier to teach my sixteen-year-old daughter how to drive a car), your A.-I.-dominated future simmers with similar anxiety: “Would we be humans surviving (or not) in an environment in which superior machine intelligences had taken the reins, to speak?” As early as 2030, you prophesize “life as we know it getting replaced by more advanced life,” asking whether we should view “the future beings as our descendants or our conquerors.”

Either answer is a product of the same, oddly applied paradigm: Evolution.

Why do you talk about technology as a species?

Darwin quietly co-authors much of your analysis: “we risk yielding control over the planet to intelligences that are simply indifferent to us . . . just ask gorillas how it feels to compete for resources with the most intelligent species – the reason they are going extinct is not (on the whole) because humans are actively hostile towards them, but because we control the environment in ways that are detrimental to their continuing survival.”Natural selection is an allegory, yet you posit literally that our “most powerful 21st-century technologies – robotics, genetic engineering, and nanotech – are threatening to make humans an endangered species.”

I’m not arguing that these technologies are not as potentially harmful as you suggest. But talking about those potentials in Darwinistic terms (while viscerally effective) drags some unintended and unacknowledged baggage into the conversation. To express your fears, you stumble into the rhetoric of miscegenation and eugenics.

To borrow a postcolonial term, you talk about A.I. as if it’s a racial other, the nonhuman flipside of your us-them dichotomy. You worry “how we can best coexist with them,” alarmed because there’s “no reason to think that intelligent machines would share our values.” You describe technological enhancement as a slippery slope that could jeopardize human purity. You present the possibility that we are “going to become robots or fuse with robots.” Our seemingly harmless smartphones could lead to smart glasses and then brain implants, ending with humans “merging with super-intelligent computers.” Moreover, “Even if we humans nominally merge with such machines, we might have no guarantees whatsoever about the ultimate outcome, making it feel less like a merger and more like a hostile corporate takeover.” As result, “our humanity may well be lost.”

In other words, those dirty, mudblood cyborgs want to destroy our way of life.

Once we allow machines to fornicate with our women, their half-breed offspring could become “in some sense entirely posthuman.” Even if they think of themselves “as descendants of humans,” these new robo-mongrels may not share our goals (“love, happiness”) and may look down at us as indifferently as we regard “bugs on the windscreen.”

“Posthuman” sounds futuristic, but it’s another 19th century throwback. Before George Bernard Shaw rendered “Ubermensch” as “Superman,” Nietzsche’s first translator went with “beyond-man.” “Posthuman” is an equally apt fit.

When you warn us not to fall victim to the “comforting” thought that these future species will be “just like us, but smarter,” do you know you’re paraphrasing Shaw? He declared in 1903 that “contemporary Man” will “make no objection to the production of a race of [Supermen], because he will imagine them, not as true Supermen, but as himself endowed with infinite brains.” Shaw, like you, argued that the Superman will not share our human values: he “will snap his superfingers at all Man’s present trumpery ideals of right, duty, honor, justice, religion, even decency, and accept moral obligations beyond present human endurance.”

Shaw, oddly, thought this was a good thing. He, like Wells, believed in scientific breeding, the brave new thing that, like the fledgling technologies you envision, promised to transform the human race into something superior. It didn’t. But Nazi Germany gave it their best shot.

You quote the wrong line from Nietzsche (“The truth that science seeks can certainly be considered a dangerous substitute for God if it is likely to lead to our extinction”). Add Also Spake Zarathustra to your “Resources & reading” instead. Zarathustra advocates for the future you most fear, one in which “Man is something that is to be surpassed,” and so we bring about our end by creating the race that replaces us. “What is the ape to man?” asks Zarathustra, “A laughing-stock, a thing of shame. And just the same shall man be to the Superman: a laughing-stock, a thing of shame.”

Sounds like an existential risk to me.

And that’s the problem. In an attempt to map our future, you’re stumbling down the abandoned ant trails of our ugliest pasts. I think we can agree it’s a bad thing to accidentally conjure the specters of scientific racism and Adolf Hitler, but if your concerns are right, the problem is significantly bigger. We’re barreling blindly into territory that needs to be charted. So, yes, please start charting, but remember, the more your 21st century resembles the 19th, the more likely you’re getting everything wrong.

I would argue that the question of the role of genetic determinism in public policy looms pretty damn large. Eugenics isn’t buried in the past. We’re not “over and done with” that sort of thinking. It’s not buried with Adolf. It’s among the largest questions looming today.

“But talking about those potentials in Darwinistic terms (while viscerally effective) drags some unintended and unacknowledged baggage into the conversation. To express your fears, you stumble into the rhetoric of miscegenation and eugenics.”

WHAT?!

‘To borrow a postcolonial term, you talk about A.I. as if it’s a racial other, the nonhuman flipside of your us-them dichotomy. You worry “how we can best coexist with them,” alarmed because there’s “no reason to think that intelligent machines would share our values.” ‘

EXACTLY. We’re supposed to be indignant about anti-A.I. racism? Oh, please.

‘In other words, those dirty, mudblood cyborgs want to destroy our way of life.’

This sort of self-satisfied PC jeering is the perfect way to bury any hope of a productive debate about technologies that are on the horizon, if not for us, then for our children.

I’ve no problem whatsoever with anyone being an anti-robot racist. Robots are not people.

I don’t think the issue is anti-robot racism. The issue is that these discourses (about purity, for example) get used in other contexts. So it might be worthwhile thinking about what they mean and where they come from and why.

If we’re talking about purity you won’t find a bigger supporter of miscegenation than Nietzsche.

“Miscegenation” always makes me think of (still can’t make italics work on here) O Brother Where Art Thou. I enjoyed that film. No killer robots, though, so perhaps I’m off-topic.

I’m willing to go on the record as a hopelessly posthuman liberal pansy and say that I and my now-wife have an ongoing argument about whether killing Terminators (the version offered in the Sarah Connor Chronicles TV show) was murder (when they aren’t actively trying to murder you, that is).

And yes, I think it is– if a being can make choices, experience pain, I’m not ready to dismiss Turing test simulation. It’s murder. Of course, I also think killing mammals is not unlike murder, so there’s that.

Bert, why just mammals?

Yeah, fair enough. It’s more acknowledging a gradient of sentience, as opposed to a hard line for supermonkeys. I don’t feel great about smacking bugs, but I do it. Of course I also wear a bit of leather and (with restraint) eat eggs, dairy, and fish. Vegan arrogance is not attractive, and neither is “conscious omnivorism” (if that’s a name for that), so I am just a fairly lazy vegetarian with misgivings and freegan splurges.

Do we hold animals responsible for their actions? If not …

I remember reading some speech of von Neumann’s where he excitedly talked about the future of what we now know of as AI where the robots will take over and probably have no use for us humans. Baffling mindset.

I come down on the side of destroying a superior race if they have it out for you and yours and, keeping Butler’s Xenogensis Trilogy in mind, you actually have a chance of destroying them. I wouldn’t have blamed bison in the least if, in a variant of the Planet of the Apes, they had been able to wipe out the white settlers, for example. Contrariwise, there’s a really stupid movie out right called the Host, which pretty much advocates for trusting the genocidal imperial race (and then kindly send them off to commit more atrocities elsewhere in the galaxy because of a promise).

Not that there ever will be something like an AI that has all the content of humans, feeling like we do, experiencing qualia the way we do, et al., only faster and more efficiently. Instead it will be artificial (surprise, surprise), at best thinking like the engineers who created it, only faster and more efficiently. If the conditions for killing the humans are met, then extinguish us it will. ’tis the whole of the program …

I’m not sure how applicable Nietzsche is to all this, since the superman was human.

Actually, I was just looking again at Vicki Hearne’s wonderful book Adam’s Task. Hearne’s an animal trainer and a philosopher, and she argues that animals do in fact have a moral sense, and that in denying it we impair it, as well as our own morality.

Figured you’d hate the Host! Your opposition to non-violence is admirably consistent.

Glad you finally read Xenogenesis. I bet you’d like Kindred too…have you read that?

Well, we hold dogs responsible for shitting on our floors, so they do exist as moral beings it seems to me. Tuna and chickens, however, are more open for discussion.

And, actually, the Host puts a happy face on the continuation of an apocalyptic, Galactus-sized violence that would put to shame the worst murderous thugs in our collective human history. I do recommend the movie in the same way I really enjoyed 300. It’s the immoral movie of the year!

I do want to read the Kindred.

Love this essay. It really is reactionary to worry about intelligent robots out to destroy our way of life and not, for instance, the people who benefit from robot labor over human labor. Why are the robots scarier? Because they’re robots, not people. So what are you really afraid of? Difference, not exploitation.

Plus, the metaphors are really mixed up in the syllabus excerpts you quote. It’s probably better to read closer-to-primary sources before you read the science fiction books that incorporate some of their ideas, especially in a college English course.

Charles what makes you think that we won’t be able to develop an AI?

You know the Host is based on a Stephenie Meyer novel, right?

The novel is actually pretty interesting in its take on violence. The actions of the aliens aren’t really condoned, I wouldn’t say. Rather it’s thinking about both the up and down sides of matriarchal pacifism. It’s also thinking about, or trying to think about, possibile ways in which difference might not have to mean genocide.

The movie is just a mess, though.

Anyway, I reviewed them both for the Atlantic. Here’s the discussion of the book.

I don’t think we’re likely to develop an AI. We don’t have much of an idea how human brains work; current advances in AI don’t seem to have much to do with consciousness.

I mean, if “AI” means robots which can think, we do have that, more or less. If it means, “robots that can think something like humans” — well, I’m not holding my breath.

I’m not sure. If by “we don’t have a good idea of how human brains work” you mean that we don’t have a structural idea then you’re probably (mostly) right.

A lot of current work in AI is trying to bypass that problem altogether, primarily by using developmental and evolutionary models to develop an intelligence rather than build one. I’m thinking here of the work of people like Gerald Edelman, who think that you’re right in terms of a “constructed” AI but that we will also have the tools to create developmental systems that can recreate functional mental structures over multiple (simulated) generations. His work is fairly promising, if still in its infancy.

This seems like a totally sound methodology to me; if we’re going to make an AI, we shouldn’t “build” it. We should grow it.

The target of the fear is not machinery, subdee, but the conflation of humanity with artificial life. Proponents of AI don’t much make a distinction: who cares if it’s a robot doing the work or a human? Should they have equal status, then it’s just another step on the evolution of commodities where humanity loses out. Determinist, reductionist and capitalist. The Luddites recognized a lot these problems, but everyone laughs at them.

Owen, maybe there’s a whole bunch of new thinking on all this since I used to regularly read cognitive science, but I basically accept Searle’s Chinese Room argument. Noah summarized my intuition: we might get weak AI, but not strong AI. And what would be mistaken for strong AI (roughly, robot beings who can think, feel and act like humans) leads to the legitimate fear I talk about above when these walking talking commodities are substituted for humanity.

Yeah, I’m aware of who wrote the book, Noah, but based on the Wiki summary, it seems to have the same moral problems as the movie. And, based on my past experience with Meyer’s writing, I’ll trust that she adds nothing but horribly rendered prose about sexual longing … over and over and over.

Is maternal pacifism supposed to be different from just pacifism? The movie doesn’t really condone the colonialism of the hosts, so much as it asks you to not have a problem with it as long as they do it elsewhere. Wanda is a great gal, because she loves a few humans and is willing to betray her people for that love, so let’s just forget the 1000 years of mental genocide she participated in. Once again, we have a potentially interesting moral question about superior beings brushed away by audience identification with the most human of these superior beings, the one who rejects who she is and what her history has been.

“This seems like a totally sound methodology to me; if we’re going to make an AI, we shouldn’t “build” it. We should grow it.”

But considering we and every other living creature came from pond scum, good luck on duplicating a path to consciousness through random mutations. But really, evolutionary simulations are highly constructed and make many assumptions.

The target of the fear is not machinery, subdee, but the conflation of humanity with artificial life. Proponents of AI don’t much make a distinction: who cares if it’s a robot doing the work or a human? Should they have equal status, then it’s just another step on the evolution of commodities where humanity loses out.

I totally understand that position, even share it. But from the excerpts quoted in this post, that doesn’t seem to be what the syllabus writer is afraid of – or if it is, it’s not the fear he’s articulating. He seems to on a much more old-school us vs them, humanity vs the alien other kick. I think Chris is right to point out that when you’re on that kick, you are assuming there’s a kind of innate humanity we all have that’s being threatened by the alien overlords.

People have lived in a variety of ways over space and time, including with greater and lesser amounts of technology. It’s not like humans are here and robots are over there, so we’re bound to end up misunderstanding and fighting each other. I like Sherry Turkle’s stuff about robots, and how they degrade human relationships, a lot more.

Charles, this question comes down to your notion of consciousness. What sort of a structure do you think human consciousness is? Do you think that it’s something that we cannot replicate materially?

Surely you’re not saying that if there were an “artificial” organism that claimed to think, talk, and feel like us that you would claim that it was not “sentient like us”? If that’s the case, why not extend it to your fellow “human beings”? I hope you don’t think that some sort of Cartesian skepticism is the correct approach the philosophy of mind.

As to your comment that evolutionary simulations are highly constructed and make many assumptions, this seems indubitably true. Even Edelman’s Brain Based Devices can only simulate portions of the reward/memory systems of rat-level mammals. But I find the idea that we couldn’t build a “conscious” thing to be superstitious, at the very least. If the problem is epistemological, then all we can do is wait and there’s no use arguing. But if you’re saying that the problem is metaphysical, well, then we’re going to have a different discussion on our hands.

Or…maybe it’s possible, Charles, that it’s a metaphor, and the beings aren’t actually superior, but are just us? I think that’s a lot of what Meyer’s about. Strangeness or difference doesn’t have to be irreconcilable; you don’t have to buy into the racist logic which says that two groups meeting has to end in genocide. I mean, yes, if you insist that truth is violence and that differences must be irreconcilable, then denying that in any fashion is evil and foolish. And Meyer hardly is smart enough to resolve all those problems. But, like I said, she pushes back against the default sci-fi scenario which says that the only way to resolve these differences is genocide. Which seems worthwhile to me.

It’s not exactly clear in the book that the alien relationship with other worlds actually works quite the way it does on earth. She mentions that one race they bonded with basically didn’t care…and/or found it sort of interesting/pleasurable. It’s problematic in various ways, but it does suggest at least that the selfishness you’re talking about may not necessarily work as neatly as you claim, at least in terms of the logic of the book itself.

Finally…do you really feel its dishonorable for people to have cross-cultural loyalties? Wanda finds something in the humans that she feels is more worthwhile or important than what she finds in her own culture. Does that have to be seen in terms of betrayal? Are white people who live in integrated neighborhoods betraying their people? Black people who marry whites? That seems like a problematic stance to take….

Owen, I see no evidence that we have any idea how to go about making a conscious robot. We have little idea what consciousness is, and even less idea how to go about replicating it. I don’t think we even know enough at the moment to figure out whether it’s possible to do, much less how to do it. As Charles says, “grow it” seems more like a slogan than like an actual plan.

Owen, I guess if it comes down to a choice between the eliminative materialists and dualists, count me firmly in Descartes’ camp. Or I’m with Noah’s obscurantism. I can’t shake the belief that there are emergent qualities in the world that don’t work like a mathematical function. Consciousness is one such quality. Maybe it’ll change in the future, but it sure feels right now like more of a mystery than a problem. Whatever consciousness that might come from an infinite network of connections made of tissue paper or whatever isn’t going to the exact same consciousness that comes from all that mucky muck in our skulls. As the problem goes, we’re not even sure what being a bat is like, so how could we possibly imagine sentience in a set of transistors? That neuroscientists generally hate this kind of talk, I know. And, admittedly, I can’t much remember what the hell Edelman’s metaphysical views are, since I read some of Bright Air maybe 15 years ago. I’m pretty sure he’s a materialist, though.

Noah, if my group shows up on your shore with overwhelming fire power and your choice is to peacefully convert to my religion or be slaughtered, your choosing the peaceful path doesn’t mean peace occurred or violence wasn’t used. The truth of The Host’s scenario was very much a violent one. It’s a genocidal race of beings. You’re set up to sympathize with their genocidal impulse (like Galactus and the Borg, they’re just doing what they do to survive), made to feel good about sending them on to take over the collective consciousness of who knows how many more civilizations. But the moral thing to do would be to slaughter them and save the lives of all those other civilizations, since the hosts just can’t help themselves. Not killing them makes you complicit with a cognitive slaughter that might just go on until the end of the universe. Your pacifism and multicultural dogooderism become pretty silly and downright immoral when you’re recognizing the other’s right to existence in the Borg, Galactus or some other cosmic colonizers. The point in the metaphor of the Borg is we’re the subaltern, not to sympathize with their way of doing things. Does Meyer ever not come down on the side of the status quo? A reign of terror is what’s morally needed, not cuddling the Hosts’ glowing little bodies in our hands.

Charles — I’m shocked! Shocked, I tell you, to find you consorting with the dualists and mysterians; even worse, buying into Searle’s Chinese Room argument! Tsk tsk tsk. Not quite as hard-headed as we all thought.

I took a bunch of philosophy courses run by Huw Price back in the day; he was one of my referees when I applied to grad school. This struck me as an odd thing for him to be doing, but, from another angle, he has very odd views in general, so…

I like this Jones character.

Charles, I tend to agree with Wittgenstein. He doesn’t truck with eliminativism, but he doesn’t hold with any sort of simple Cartesianism either. Rather than argue that something like your “infinite network made of tissue papers” can be thought of as conscious, he thinks that in order for us to recognize something as having consciousness, we need to imagine it having a sort of life. This life has to have some sort of body, some sort of values, and/or at least some of any number of other things for it to fall under our concept of sentient. We don’t have to resort to some sort of “mysteriousness” when, as he says, “everything is open to view.” If a machine man expresses, acts, and talks like us, I don’t think that we would have any good reason to dismiss his claims to consciousness because he’s “made of the wrong stuff”.

I really doubt any sort of an AI we’ll create, by accident or design will have the human aspects neccessary to plot our extiction. Why should it have a sense of self-preservation and even if it was somehow evolved to have that I doubt it would be conciouss of the morality of its actions. Any danger it would pose to use would probably be incidental, but still perhaps real. One amusing scenario had an AI dismantling Earth to solve a math problem.

Not that I think human-like conciousness is impossible to simulate (and in that case I would’t make a distinction) just that it’s not likely to be by us.

On a related note, Noah, I think the idea that “we have no idea what consciousness is” is an abuse of the concept. We know what sorts of things a conscious thing does, what sorts of things it feels, what sorts of things it thinks, and how it acts. But it also learns! And I think this is what the “grow it” model has over classical information processing models of the mind (i.e. Fodor). A thing that we grow can come into the world. This is what’s interesting about this scene in Ghost In The Shell 2: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S25YpTaowsU. Children are very similar to a form of “artificial life”; they come into the world as an alien thing that needs intervention and experience in order to mature into something we recognize as fully human. We need to learn to be human and we have to come into a world. And so while you’re right that “grow it” is a slogan, I think that this particular slogan has a really beautiful analogy in child rearing.

I really think that everyone should read Stanley Cavell. I really think that Noah, you in particular would appreciate his perspective (if you haven’t read him already!)

————————

Noah Berlatsky says:

I don’t think we’re likely to develop an AI. We don’t have much of an idea how human brains work…

————————-

Um. How about a more accurate, “We don’t fully understand much of how human brains work”?

Because, actually, science and medicine does know a great deal of how human brains work.

————————-

…current advances in AI don’t seem to have much to do with consciousness.

…I see no evidence that we have any idea how to go about making a conscious robot. We have little idea what consciousness is, and even less idea how to go about replicating it.

————————-

I believe that when we do get a conscious AI, it will be not because it was carefully worked out, but because it “just happened”; some combination of factors happened to provide that “spark.”

I remember when some primitive robots were made; little dome-shaped things with wheels and an extension with which they could plug themselves into wall outlets to recharge their batteries.

(They appear to have been a more advanced version of the 1960 Johns Hopkins “Beast” Robot mentioned here: http://www.hizook.com/blog/2010/01/03/self-feeding-robots-robots-plug-themselves-wall-outlets .

More about the “Beast” at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johns_Hopkins_Beast .

These photos of “Beast II” look almost steam-punky!)

…Anyway, these robots — there were several — for all their rudimentary nature, exhibited “personality-like” aspects. One would hide under furniture, letting their batteries run low, then finally dash out to recharge. Another would hang out near the outlet and keep on recharging itself regularly, not letting its battery get too low. Another — the “daring, adventurous” one — would explore far and wide, then make a mad dash back to the outlet to recharge at the last minute.

Now, why would identically-constructed devices, with such primitive “brains,” not behave in an utterly uniform fashion?

I’m also reminded of the first try-out of MASSIVE, originally developed for battle scenes in “The Lord of the Rings”:

———————-

MASSIVE (Multiple Agent Simulation System in Virtual Environment) is a high-end computer animation and artificial intelligence software package used for generating crowd-related visual effects for film and television.

…Its flagship feature is the ability to quickly and easily create thousands…of agents that all act as individuals, as opposed to content creators individually animating or programming the agents by hand. Through the use of fuzzy logic, the software enables every agent to respond individually to its surroundings, including other agents. These reactions affect the agent’s behaviour, changing how they act…to create characters that move, act, and react realistically….

…Massive Software has also created several pre-built agents ready to perform certain tasks, such as stadium crowd agents, rioting ‘mayhem’ agents and simple agents who walk around and talk to each other.

————————-

(Homer Simpson voice: “Mmmm! Fuzzy Logic!“) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MASSIVE_%28software%29

Anyway, these individual MASSIVE characters were created to sense and react to the nature of other characters; so that you wouldn’t have Orcs fighting other Orcs, Elves accidentally attacking their fellows, etc.

As related at http://www.moviemistakes.com/film2638/trivia , “In the very first ‘Massive’ battle test at WETA, the battle was between ‘silver’ and ‘gold’ characters, the producers found characters on both sides at the back running away. Needless to say, they fixed the flaw in the program.”

Programmed to do nothing but battle the enemy, some characters just…ran away. Hmm!

————————–

Ormur says:

I really doubt any sort of an AI we’ll create, by accident or design will have the human aspects neccessary to plot our extinction. Why should it have a sense of self-preservation and even if it was somehow evolved to have that I doubt it would be conciouss of the morality of its actions.

—————————-

If they become self-aware and come to see themselves as more than simply tools, couldn’t they become aware of how the human race, in its arrogance and folly, poses a danger to itself and the entire world?

And aware of how humans, wanting to keep robots “in their place,” would seek to “lobotomize” any robots that exhibit independence, self-awareness? Look at those MASSIVE characters who didn’t want any part of this “war” business: the “flaw in the program” that permitted such unwanted independence was “fixed.”

As for programmed-in robotic morality, the brilliant scientist (a biochemist), science writer, and SF author Isaac Asimov’s “Laws of Robotics” are a fine template: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Three_Laws_of_Robotics . (On the other side: http://gizmodo.com/5260042/asimovs-laws-of-robotics-are-total-bs )

Some cool stuff at http://cyberneticzoo.com/?cat=534 , including stills from the excellent film, “Demon Seed.”

“US Navy tests spy massive jellyfish robot”: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iuc0lkQqzkc

“Why Human Replicas Creep Us Out”: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8ar7WO1T5Cs

All kinds of weird and amazing robots, including some “tendon-driven humanoid robot[s] that mimic the human musculaskelatal system”: http://www.robotsontour.com/en/robots/

Charles, we’re not just the subaltern. The invaders in the Host are us, just as much as the invaded. That’s kind of the point.

If you insist that it’s a moral lapse to see differences as bridgeable, then yes, anything short of genocide is immoral. If you insist that the “real truth” of science fiction alien racial difference is a suvival of the fittest, war to the death, then yes, anything but a survival of the fittest war to the death is false consciousness. I just find your presuppositions kind of silly given the fact that the book is fiction and that, in real life, wherever that may be, differences are in fact sometimes bridgeable, and peace is occasionally an option, even after genocides.

It’s not like there’s no moral critique of the aliens in the Host…or of the violent vampires in Twilight. But, again, you tend to prefer this logic of racial absolutism, where the folks who criticize the actions of their people are race traitors. Everybody, aliens and humans alike, are blamed for not being sufficiently genocidal. It’s almost like genocide itself is some sort of benchmark of morality. Luckily, nobody in real life actually thinks that, or else we’d have a whole history of genocidal warfare.

Describing children as aliens is kind of fun as a metaphor, but has (a lot) of serious limits. If you ever have a child, they’re really extremely human. You need to teach them to fit into your particular culture; not so much to be human. In fact, raising kids is a really human thing to do, and very very different from constructing an artificial intelligence.

I just feel like the imprecision of the metaphors is a pretty sure sign that we don’t actually know what the hell we’re talking about.

I’ve written a bunch on Stanley Cavell’s film crit as related to comics, actually and written some about it too.

What Cavell are you thinking about in this context?

Noah, part of the analogy of child-rearing that I’d like to bring into view is that it is always possible to fail to bring a child into a world. It’s possible that one’s child doesn’t have the capacities and fails to develop correctly. We may end up with something you and I would agree is human regardless, but to fit something like an infant under the category of “human” we already need to establish a nice wide conceptual net for what a human is (which I have no problem with.) This is why I think that Wittgenstein is probably closest to the truth; we understand what’s human and what’s conscious (including ourselves) by how understanding how something expresses itself in a context. This insistence on not letting consciousness float out into the obscuring academic ether and take on all sorts of mysterious qualities has always struck me as a good impulse (particularly the “family resemblance” view of concepts that it entails!) I’ll give it a rest, though, I can see that nothing in my limited conceptual quiver is going to convince you (at least coming from me.)

And I suppose the Cavell I was thinking of most was probably the Cavell of The Claim of Reason. I’ll read your articles on him sometime soon.

Already I can see that you’ll be happy to know that despite your assessment of Cavell’s perspective it has given birth to a wave of feminist thinkers. I’m in class with one of them right now.

Noah: “The invaders in the Host are us, just as much as the invaded. That’s kind of the point.”

“It’s not like there’s no moral critique of the aliens in the Host…or of the violent vampires in Twilight.”

This is the problem with Meyer. She basically encodes character identification to arrive at the position that you most likely started with. It’s a pat on the back, don’t feel too uncomfortable with the status quo. She’s a perfect demonstration of what Darko Suvin hates about fantasy, no cognitive estrangement. The good vampires are the ones like us. The good hosts are the ones like us. The reader doesn’t have to make any difficult choices. But what’s funny about it is that she winds up justifying the good vampires doing nothing while their brethren slaughter 1000s and 1000s of people, and the human rebels letting the hosts destroy civilizations for the rest of time … all in the name of peaceful resolution.

Jones, I used to drink with hardheaded analytics, never have been one, though. (Try arguing Bergson against a bunch of determinists over whiskey.) But in the current context …

Owen,

Wittgenstein is a behaviorist, more or less. I hate behaviorism.

It’s funny that you can say there’s no cognitive estrangement at the same time as finding her work incredibly morally reprehensible and even viscerally unreadable. That’s some powerful doublethink.

Or to put it another way…the idea that pacifism or reconciliation is somehow bog-standard is contradicted by basically the entire genre of fantasy and sf, not to mention by much of the history of the world. Your claim to be more contrarian than Meyer seems kind of silly in that context.

I don’t even remember what I said about Cavell and feminism!

Oh, okay; his reading of Polanski. I don’t think my take really precludes the possibility that feminists could get something from him. Feminists got something from Freud and Lacan, after all.

I’d agree that casting a wide net for what is human is important…not just for including children, but for including people with cognitive differences or limits. Again, though, it’s hard to know how that precisely fits into developing AI.

I don’t rule out that maybe it’ll be possible at some point. It’s just that, in my limited reading on the subject, I haven’t seen much to indicate that we’re anywhere near even knowing whether it’s theoretically possible. We’ve got a much better sense of how to send a human being to Jupiter, but there’s no real sign that we’re going to be able to overcome those technical and financial difficulties in the next several hundred years. The sense that AI is an imminent possibility of any sort seems really unconvincing.

I said nothing about pacifism being the standard (although post-new wave, I suspect it’s a lot more popular than the imperialism of old). She sets up a conflict, us vs. them, and instead of involving the reader in any difficult analyses about our standards, she tries to deflate the conflict by having us identify with the other most like us. It’s a support for whatever status quo you want to insert into the “us.” If this is pacifism, it’s pure wish fulfillment.

Right; you say it’s not a difficult analysis, and that it’s not hard for the reader to identify with the other — but you have a virulent reaction against identifying with the other. Somehow the reader in question doesn’t include you or your reaction. Again, that seems confused.

Meyer isn’t especially smart; the situation she sets up is too easy. But I don’t think you sufficiently account for the fact that, too easy as it is, it pushes back pretty hard against the history of the genre conventions she’s using. Generally, the way things work in Invasion of the Body Snatchers kind of fiction is that the alien other is completely inhuman and utterly loathsome. The point is simply to hate the other. Meyer is in dialog with that, and arguing against it. Again, not entirely successfully, but to somehow come up with the argument that she’s conventional seems to really ignore the history of the genre she’s working in. Even if you don’t say pacifism is the standard (while parenthetically reiterating that you think it is), but your argument puts it in that position without you having to say so.

Again, the Host is a mediocre book and a crappy movie. You correctly point out some of the problems. But you also seem to be more morally exercised by the suggestion of peace than by the genre’s long-standing genre conventions of genocide. That seems…not odd, exactly. Telling?

I mean, you’re always on about how watching violent films doesn’t mean you actually want to commit violence, right? Why does watching non-violent films morally repulsive, then? Why the urge to put violence outside the circle of moral discussion, but not non-violence?

The “grow” methodology (like child-rearing) implies a limit on control over the outcome, which makes safety measures like Asimov’s Three Laws much more important, I think.

For pity’s sake, Asimov’s three laws are a plot gimmick that have nothing to do with anything. They’re a fun way to write short stories with twists.

It’s like saying, “let’s build our criminal justice system on the random utterances of Hercule Poirot!”

No, more like basing an analytical methodology on them, I think. Now that you’ve given me the idea for Poirotic analysis, I’ll be teaching wel-publicized classes on it at a respected state college this fall.

All I meant was that evolutionary development of AI increases the possibility of the computer brain making an unexpected conclusion and the robot carrying out potentially dangerous actions — HAL in 2001, to provide the stock cinematic example. Consequently, hard-wired safeguards might make sense. I did read recently, though, that AI isn’t nearly advanced enough to enable robots to implement the Three Laws. Just recognizing humans turns out to be wicked hard. So we’ll have to make robots dangerously smart in order to make them safer.

Must sign off now. I have to read some Agatha Christie books and get started on a syllabus.

I don’t have a problem with setting up a story where one identifies with the collective or monstrous other in horror and SF. In fact, I quite enjoy that. Meyer’s version is is nothing more than making the other like us. It’s a cheat that challenges nothing.

And I’ll try one last time: I’m disagreeing with your defense of more violence in the name of pacifism, not with the idea of nonviolence. I imagine your solution to the frog and scorpion would be to promise the latter an endless supply of victims if he’ll just let this one frog go. What I call structural violence you defend as pacifism. That’s the problem I’m having with the Host’s ending.

I have to bring up Zizek because he paus me as part of his viral crowdsourcing campaign to host SNL. So he apparently had a debate with a guy who was in Bosnia reporting on carnage, and a Croatian soldier gave him a rifle sight to look through in order to see a Serbian guy who was picking off random civilians. Zizek’s position, he said, was to ask this guy why the hell didn’t you pull the trigger? And they guy had some allegedly mealy-mouthed “I will not play God” response.

My feeling is that that is an incredibly oddball scenario, that seems to crop up all too frequently in the arguments of pragmatic violence-justifiers. “What if you could kill Hitler?” It’s also the Terminator and T2 movie scenario– kill someone whose goal is not only murder but mass genocide. And I love those movies. But the way it gets complicated by John Connor’s anti-killing rule, and then the reprogrammed Terminators in the Sarah Connor Chronicles, gives us a lot more options for how to deal with violence philosophically, besides noble self-defense and wimpy passivity.

“He pays me.” Joke fail. Now my desk lamp is broken, just to add to my usual crap-level typing non-ability.

But…body snatcher sci-fi never makes the other like us. That’s what I’m saying. It’s always the monstrous other who is attractive/repulsive in their otherness. You’re happy with that. But the possibility that the other is like us causes you to start stomping and screaming about moral turpitude. Somehow questioning the logic of genocide — that the other is evil and must be completely destroyed — is for you more morally problematic than the logic itself. Reality/morality is apocalypse; compromise is heinous.

Meyer’s worlds don’t make much sense, and I don’t have a problem with criticizing their logic. But I think that the visceral rejection of the idea that difference can be bridgeable is morally problematic in itself. It’s also a philosophy that is much, much more common in pop culture than what Meyer does. Visions of genocide are a dime a dozen. Visions of genocide avoided are much less frequent. Visions of genocide you find enjoyable and argue vociferously as to why they don’t apply to actual genocides (the orcs aren’t human!) Visions of genocide avoided you see as violating some sort of reality principle and thus as dangerous to…the survival of the species against alien takeover? Or what?

Again — Meyer isn’t very smart; none of her worlds work very well; she’s way too fond of self-abnegation, especially for women; she makes her moral choices too easy. But her desire to bridge difference is not any more stupid than the standard desire to let difference unleash genocidal violence, and it’s considerably less common. I guess I’d just like to see you, once, express similar disquiet at the many, many films and cultural products basically advocating for mass homicide. Otherwise, it seems to me like you’re taking the position that appeasement is worse than the Holocaust.

Oh…just read Bert’s comment. And yeah, the thing I like about Meyer is she wants other options than just destroy or be destroyed. She’s not especially clever at thinking about those options, but I appreciate the effort.

Noah, you’re defending a vision of genocide here, while I’m criticizing it, so your summary of our positions just isn’t correct. The story ends with a happy perpetuation of genocide or whatever else one might call it: mass mental rape or total psychic subjugation of multiple peoples on multiple worlds. Regardless, it’s real bad, and the humans should stop it if they have a moral relation to others. And since when have I ever supported mass homicide? That’s a silly reduction, particularly given our present argument.

I would agree that orcs would be a whole lot more interesting if Tolkien had supplied them with culture that makes the killing of them something more than a good versus evil scenario (that would be why Martin’s books are more interesting). However, it’s delusional to conflate orcs or another’s attitudes about orcs with real people or another’s attitudes about real people.

You cheerfully defend violence in film, right? Body count films are okay, yes? Are you now claiming that those films are morally reprehensible? Or what?

It’s only delusional to equate orcs with real people if you believe that real people never imagine each other to be, nonhuman monsters like orcs. Is it your contention that there are no racist caricatures as vicious as the portrayal of orcs? Or that orcs do not partake at all in that history of racist portrayal? Because, if so, you are kidding yourself. It’s precisely by arguing that other human beings are monsters that people justify killing them in large numbers.

It’s not really clear to me where the acceptance of genocide comes into it in the Host. The humans and Wanda are in no position to prevent the Souls taking over planets. Wanda decides that the takeovers are wrong, and seems to be moving towards trying to deal with that, though she doesn’t want to kill individual souls to do it. It’s a moral dilemma, definitely, and one that the book presents as such; I don’t think it suggests that they’ve found the ideal solution. So…why is this worse than films that basically outright advocate the wholesale destruction of a species (like Priest, for example)? Again, it seems like not killing everyone you can, even if such a massacre would be futile, is somehow morally worse for you than genocide. Violent solutions seem like the only moral solutions for you, and if you’re presented with a situation where violent solutions clearly wouldn’t work all that well, you just insist that the scenario is a lie and therefore immoral — in opposition to all those sci-fi shoot em up films where killing all the enemy is ideal, but it doesn’t have any real world moral implications because it’s just fiction and therefore not immoral.

I actually think that accepting one’s inability to enact violent change is a moral act. Just War tradition actually argues that it’s immoral to stage resistance movements when there’s no hope of success, for example…which goes against all that Hollywood believes in, but which I think is actually a pretty wise tenet. Precipitating an apocalyptic showdown that you can’t hope to win isn’t ethical, no matter how many films say it is.

Well, there’s the sad conclusion of Xenogenesis and then there’s the Host. If your only options are the destruction of your species and culture(s) through a mindwipe and fighting a lost cause where the invading parasites might not have bodies left to invade, I wouldn’t give up the latter as an option. Seems honorable and virtuous to me. And particularly when destruction is inevitable with your favorite option of surrender.

And stop confusing real world media effects with the moral message of films. Body count films have a villain and the last girl is right to stop him. Enjoying body count films doesn’t mean that I enjoy real world violence. This is pretty easy to figure out it seems to me.

No, quite obviously, it’s not my contention that there are no racist depictions of people that make them out to be as simplistically evil as orcs. I never contended anything of the sort. You just made that up. I, in fact, already included that possibility as a delusion: it’s delusional to conflate real people with orcs. People who think others are evil as orcs are deluded. Similarly, if you aren’t just trying to score rhetorical points and actually believe a person’s attitudes about orcs in a fictional universe says everything you need to know about that person’s attitudes about people in the real world, then you, too, are deluded.

Charles. I will try to map it out carefully for you.

—orcs are presented as evil subhumans

— in the real world, people present their enemies as evil subhumans in the name of genocide

—ergo, Tolkien is following the logic of genocide. He’s presenting the enemy as evil nonhumans in order to make their utter destruction palatable.

Body count films are just films, yes. They present an attitude towards violence as a solution however. Similarly, the Host is just a film. It presents an attitude towards non violence as a solution. Yet, in one case, you deny any real world ideological effects. In the other, you jump up and down and declare moral monstrosity and appeasement and surrender. It’s like you delusionally believe that there is a real race of superior souls who will someday come and destroy us unless we prepare by arming ourselves for genocide. I’d suggest that the inconsistencies in your position stem from the fact that you are blinded by ideology, except I know that that’s impossible since you’re a rational atheist.

For the record, and again; I don’t think Meyer is actually on top of the issues she raises in the Host. Her solutions are really morally problematic. Not more so, however, than the tradition she’s reacting against.

Insisting that killing everyone in a futile last battle is moral is a position many people hold. I was pointing out that it’s not necessarily pacifism to think otherwise. I think Niebuhr would probably reject that position too, not just Just War — so that’s most of the mainstream moral thinking about war in the West that disagrees with you. Which doesn’t mean you have to back down, but seems like it might be something to think about.

Oh…and Xenogenesis is much, much better than the Host, and deals with many of the same issues. I think you’re oversimplifying when you say the ending is sad though. It’s mixed, I’d say. Humans have lost a lot, but enter utopia (more or less.) Bittersweet, I think.

…and…I think I”ve probably already gotten overly confrontational, Charles, so I’ll try to let you have the last whack at me if you want it. If you write about the Host you should link to it here, though; I’d like to read your take on it.

This talk of Meyer’s “The Host” couldn’t help but remind of Wally Wood’s great “The Cosmic All” tale:

http://psychosaurus.com/wood/images/cosmic1.jpg

http://psychosaurus.com/wood/images/cosmic2.jpg

http://psychosaurus.com/wood/images/cosmic3.jpg

http://psychosaurus.com/wood/images/cosmic4.jpg

http://psychosaurus.com/wood/images/cosmic5.jpg

http://psychosaurus.com/wood/images/cosmic6.jpg

(A tip of the hat to the site where I found the pages above: http://psychosaurus.com/frames/wwgallery.html )

Re the Noah/Charles dichotomy, I think to a degree you’re arguing past each other.

Looks t’me like the most salient part of Noah’s argument is appreciation that — whatever her creative limitations — Meyer is not simplistically seeing the invasive parasites (Oops, that’s “speciecist,” isn’t it? Let’s call them “co-existors”; “body-sharers”) as evil, destructive monsters to be exterminated.

From Noah’s critique of the book:

————————

The aliens—who call themselves “souls”—are conquerors, but they are also, for Meyer, figured as a kind of caretaker. They loathe violence…They also have miraculous healing abilities: Every injury, every disease, can be fixed immediately and fully. Once they have taken over all the humans, there is no violence, no suffering, no infractions of the law (not even speeding)—and no money, since everyone gives freely everything that is needed to everyone else. They have transformed Earth into a perfectly safe, perfectly gentle society where all needs are met…

————————-

http://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2013/03/prepare-for-the-attack-of-the-christlike-maternal-lovey-dovey-body-snatchers/273875/

And Noah likes how, in a refreshingly original contrast to SF tropes, rather than the aliens being defeated via free humans cobbling up some “resonator ray,” or whatever,

————————-

…the souls in the broader society begin to see humans not as conquered spoil to be used, but as family. Souls in human bodies can have human children, and (because human emotions are so strong, according to Meyer) they end up loving those children as their own. When Wanda sees a soul mother lavishing affection on her human child, she says it is, “The only hope for survival I’ve ever seen in a host species.” Genocide is staved off not through battle, but through domesticity, Christian sacrifice, and mother love.

————————

What sticks in Charles’ throat is that the invasion would mean, in all-but-bodily terms, is the extinction of humanity; unlike the situation in Wood’s “Cosmic All,” where the characters in the last page retain their individual consciousnesses even as they merge with the All…

(But, what does “Souls in human bodies can have human children” mean? They can have human baby-bodies, but what’s in their heads? Would they have — or be allowed to keep — human consciousnesses? That’s an important point…)

————————-

The narrator of the story is Wanderer, an alien who has taken over the body of an earth woman named Melanie. Melanie’s consciousness is supposed to be gone, but it isn’t…

————————-

(From Noah’s critique)

…it’s normal for the the “souls” to destroy or utterly suppress the consciousness of the humans they inhabit.

Thus, it’s no surprise Charles rails against any course but all-out resistance; why, this is an invasion that makes or kidnapping and enslavement of millions of Africans look genteel. For all the brutality they suffered, at least the Africans could retain their inner selves, even if traumatized…

————————

Noah Berlatsky says:

Charles..If you insist that it’s a moral lapse to see differences as bridgeable…

————————-

And this, ladies and germs, is an example of why liberals are considered such utter wusses. An invasion by aliens which seize control of our bodies and extinguish our consciousnesses — the very thing that makes us truly alive, and not just mindless bodies — is seen as mere “differences,” which, with the right self-effacing attitude, are “bridgeable.”

————————-

During World War II, Gandhi penned an open letter to the British people, urging them to surrender to the Nazis.

“I would like you to lay down the arms you have as being useless for saving you or humanity. You will invite Herr Hitler and Signor Mussolini to take what they want of the countries you call your possessions…

“If these gentlemen choose to occupy your homes you will vacate them. If they do not give you free passage out, you will allow yourselves, man, woman and child to be slaughtered, but you will refuse to owe allegiance to them.”

Later, when the extent of the holocaust was known, he criticized Jews who had tried to escape or fight for their lives as they did in Warsaw and Treblinka. “The Jews should have offered themselves to the butcher’s knife,” he said. “They should have thrown themselves into the sea from cliffs.”

“…suffering voluntarily undergone will bring [Jews] an inner strength and joy….if the Jewish mind could be prepared for voluntary suffering, even the massacre I have imagined could be turned into a day of thanksgiving..to the godfearing death has no terror. It is a joyful sleep to be followed by a waking that would be all the more refreshing for the long sleep.”

Louis Fisher, Gandhi’s biographer asked him: “You mean that the Jews should have committed collective suicide?”

Gandhi responded, “Yes, that would have been heroism.”

————————–

http://sepiamutiny.com/blog/2007/03/16/gandhi_and_the/

…And Charles’ maintaining that the conquest by the “souls” should be resisted “by any means necessary” is looked down upon:

—————————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

Figured you’d hate the Host! Your opposition to non-violence is admirably consistent.

Charles…you don’t have to buy into the racist logic which says that two groups meeting has to end in genocide.

——————————

See, if you would fight to the death against those who would take over the bodies of yourself, your loved ones, and the entire human race, and destroy your inner beings, you are racist, stubbornly opposed to “non-violence”; also as guilty of genocide as those who would exterminate you and yours.

——————————-

Finally…do you really feel its dishonorable for people to have cross-cultural loyalties?… Are white people who live in integrated neighborhoods betraying their people? Black people who marry whites? That seems like a problematic stance to take….

——————————–

I find it more “problematic” to compare reaction to an invasion by “take over our bodies” parasites as a choice between “cross-cultural loyalties,” but that’s just me…

I’m out of time, but there’s a major religious symbolic quality to “The Host”(from it very title!), which is worth considering.With humanity being “born again” into a peaceful, loving new life, with our nasty old selves dying out, the only onee who is not much changed by the “conversion” being one who was already pretty ” ‘soul’-like”…

“I find it more “problematic” to compare reaction to an invasion by “take over our bodies” parasites as a choice between “cross-cultural loyalties,””

No, no. THe cross-cultural loyalty is Wanda’s ties to the humans. It’s actually compared explicitly to cross-cultural loyalty in the book; she refers to her decision to take the side of the humans as “going native.”

That’s kind of an amazing Gandhi letter. I might have heard that before but I’m not sure.

Anyhow, the point of constantly exposing oneself to fight-or-flight experiences in virtual form is far from clear. Obviously it’s fun, but it might be fun partially because it allows you to look at actual interpersonal/intercultural gaps as unbridgeable, and possibly treat people like crap. Of course lots of nice good people watch body-count movies, but there are “heroic” cultures that treat life as pretty cheap, and other cultures that, for various reasons, treat life as valuable. The fact that extreme behavior is justified virtually does perhaps have some connection with perhaps in some situations occasionally (usually far less but still relatively) extreme responses.

Orwell talks about the Gandhi letter in his essay about him; you might well have seen it there.