The index to the Comics and Music roundtable is here.

______________________

“There was no working title for the album. The record-jacket designer said `When I think of the group, I always think of power and force. There’s a definite presence there.’ That was it. He wanted to call it `Obelisk’. To me, it was more important what was behind the obelisk. The cover is very tongue-in-cheek, to be quite honest. Sort of a joke on [the film] 2001. I think it’s quite amusing.”

-Jimmy Page

On the one hand, the black object there in the center of the bourgeois family may indicate Zeppelin’s power and force, as Jimmy Page suggests — the God’s uncanny presence. The happy family dinner, the smiles, the upper-crust yachts in the background; the black finger in the center, with its calibrated, meticulous wrongness, reveals the cheerful 50s nuclear family as paper-thin pasteboard. Zeppelin’s mere presence reveals and knocks apart their uncanny inanity.

Robert Plant was in a car accident on the Greek island of Rhodes before the recording of Presence, and ended up in a not especially sanitary hospital. He recalled:

I was lying there in some pain trying to get cockroaches off the bed and the guy next to me, this drunken soldier, started singing “The Ocean” from Houses of the Holy.

Led Zeppelin was the Beyoncé of its day; ubiquitous and omnipresent. Page doesn’t sound quite like he’s reveling in that omniPresence, though. On the contrary, with the cockroaches and the pain, there’s something decidedly Gothic about this encounter with a drunk foreign ventriloquist doppelganger. A broken has chased him down across the globe in order to mirror, with pitiless vacuity, his broken self.

Isn’t there, then, also a kind of vulnerability, a diminutive interrogative, in the way the object twists itself around, bending its non-face, half coy, half nervous, to the giant mannequins who loom above it? The smiling, cheerful normality of the adults and the blank featurelessness of the children, all captured in high focus, suggest a certain feral threat — a hungry falseness. Perhaps that hungry falseness is ours, too, when the family is gone and we replace them around the Object.

Zeppelin may be that object itslef, but its objectness has passed out of Zeppelin’s control. It is now a public totem, doomed to ingratiate even at its most idiosyncratic, and individual — or, as Tom Frank would have, especially at its most idiosyncratic and individual. Like Plant regaled by his own tunes at the butt end of noplace, celebrity and self wait everywhere, mouths open. The Object is not crushing all around it. It is simply surrounded.

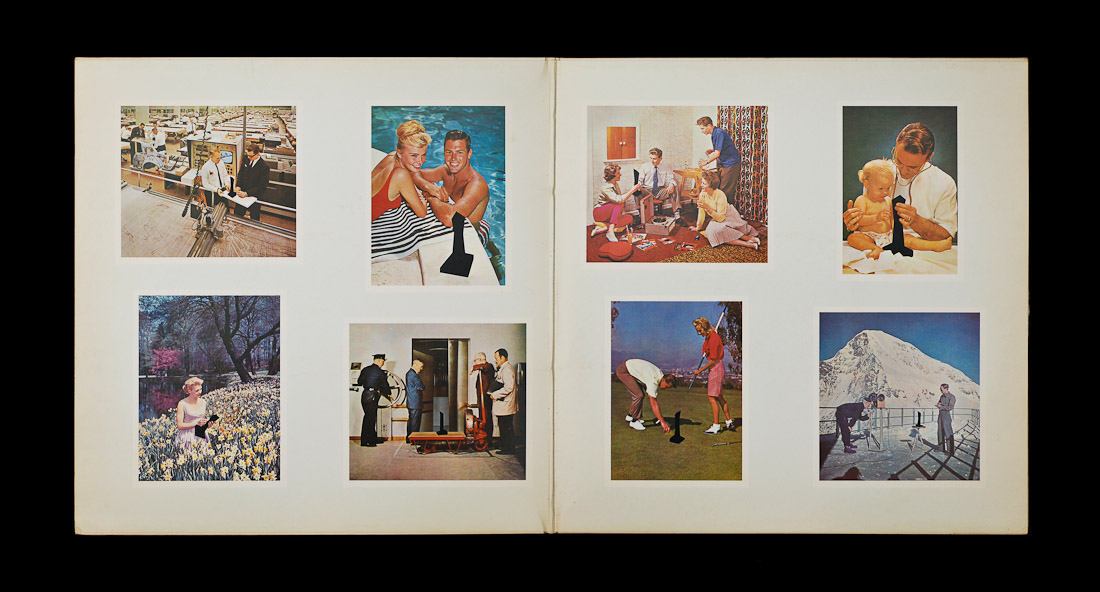

Perhaps, though, Zeppelin isn’t the black Object — or at least, not just the black Object. After all, the images chosen for the album art — the cheerful, healthy couple at the pool; the immaculate golf green; the serious researchers investigating — all seem picked in no small part not just for their blandness, but for their bland non-blackness. The normality on offer, the default scrubbed cheer, is white — insistently so in the dress of the woman amidst the flowers, or the snowy peak of the final image.

The photographer, though, is not filming the snowy peak, but the black Object, just as the happy family is turning from their dull (Pat Boone?) records to the new twisted, exciting thing.

Again, that new twisted exciting thing could be Led Zeppelin itself. But the tableaux could also be seen as a kind of re-enactment, or parody, of Zeppelin’s own relationship to racial performance. Plant’s weirdly abstracted, soulless moans at the beginning of “Nobody’s Fault But Mine” as the sturm und drung flatten the gospel humility under towering psychedelic mannerisms, just as the miniaturized and humble object disappears into a warehouse of cerebral study in the upper left hand image. Plant’s eager I’m-James-Brown-no-really emoting on “For Your Life” seems to reach for swagger and cred in the same way that the baby reaches for the black object phallicly positioned between its legs in the upper right. And given the Elvis-shake on “Candy Store Rock,” the doctor there, carefully handling the Object’s tip, might be seen as representing an older generation of borrowers, passing on the appropriation to the curious but willing infant acolytes.

From this perspective, it’s not the Object which is uncanny, nor the aggressively smiling giants looking down on the Object, but rather the juxtaposition of the two. The weird funk funeral march of “Achilles Last Stand,” with its drifting hippie lyrics and Plant howling like a ghost being scraped across steel girders, is a kind of photonegative of that smiling couple looking at the thing; satyrs running through the iron city, rather than warbots dancing in a midnight glade. Zep’s distance from its sources is figured in the images, and perhaps in the music, not as authenticity but as wrongness. The black Object haunts the mountain and the white mountain haunts the Object, in the iterated symbiosis of the dead.

Comics generally represent motion through repetition; the same body or figure is drawn in one space and then another to show the passage of time. Music, on the other hand, seems to fill space; it’s everywhere and nowhere. Its repetitions through time are both insistently present and invisible.

The Object seems to ambivalently take part in both these structures. It could be seen as moving from location to location; starting the week with dinner at the yacht club and finishing up in a schoolroom. Or it could be seen as inhabiting all paces simultaneously; a broadcast received at once by the poolside, the bank vault, and the golf course. Or perhaps it could be seen as inverting both these options. Maybe it’s the Object that sits in one place, while the smiling people and their hollow world flicker and hum around it.

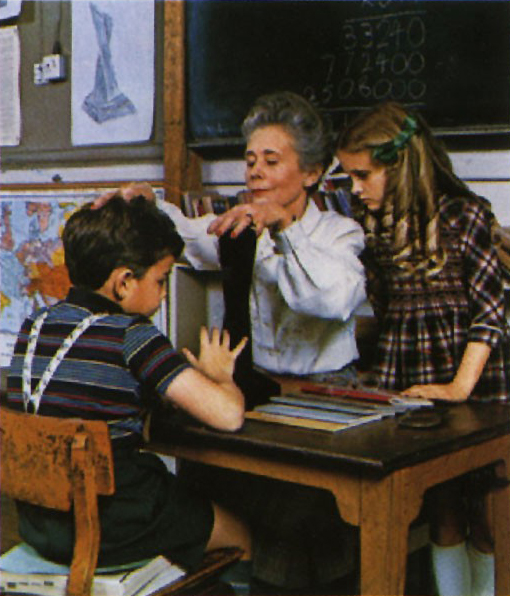

The image above is the only one where there are two objects, or an object and its image. The teacher seems to be trying to hear or see the boy’s mind; the drawing on the wall could be his thought bubble, or hers. In either case,or neither, it’s someone’s duplicated representation of a thing which is not a thing, sort of like a comic about music.

So the black phallus could really be “the Black phallus.” I always thought of it as the sort of petit-objet-a void that stitches reality together, but that’s Wallace Stevens’ fault.

I think it could be both; clearly it’s trying to be ambiguous, right?

I like the dialectical certainty-uncertainty arc there. “Clearly,” “ambiguous,” “right?”

I also think it’s kind of what all advertising looked like in the ’70s. It’s not unlike that Melvins Houdini cover actually.

The Melvins’ cover is cartoony though….

Hypnogosis (the folks who did this one) did a bunch of others, so that may in part be what you’re keying into….?

Well, in the ’70s I was a child, and every board game had happy white people looking really excited about trivial pastimes. The happy blonde kid with the puppy on Houdini is the same kind of schlocky propaganda (though yes, it is a cartoon), with an element of evil added.

Because that’s the other thing about the black Thing. It’s clearly evil. “Don’t touch it, it’s evil!” (to quote Time Bandits)

I need to see Time Bandits again….

Your point about 70s kitsch is well taken. The evil of kitsch has maybe even been over-explored by lowbrow at this point, but it’s still evil….

What’s enjoyable is that pop musicians were deploying that kind of Pop arch irony from the start (which is why true Adorno-lovers could never really get into Pop art).

The object is the spirit freely released into nature. That’s the Hegelian version.

Hah! Hard to see where freedom or nature quite fit in the Zeppelin version…

It’s nobody’s fault but mine that I left my big black dildo in Antarctica.

Testify.

Very nice essay! I couldn’t help but wonder about the black sculpture appearing, Zelig-like, in all those old photos. In the days ‘way before Photoshop, I’d imagined laboriously stripped into the photos; but the piece below says they were painted in:

———————

The Presence “Object”:

I get LOTS of questions about the famous statue that was on the cover of Led Zeppelin’s Presence album, which is called “The Object”. Hopefully this feature will give some background on it and answer some questions that commonly arise!

First of all, after Hipgnosis designed the Presence album cover, in which The Object was painted into the various scenes, Led Zeppelin had real Objects produced. That’s what was used to photograph the album’s black and white inner sleeves. Shortly thereafter, Alva Museum Graphics in New York was contracted to produce 1000 individually numbered 12″ tall black Objects for Swan Song to use in their promotion of the record…

Both Originals and Repros were made of a hard plaster called hydrocale…

———————-

http://zeppelincollectables.com/pages.php?pageid=4

No info on who sculpted the darn thing, unfortunately! Though I guess it was by a designer from Hipgnosis…

Led Zeppelin explains the “Object” from Presence: “http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FVrsdVqprtk (Can’t listen to it without waking the Missus; hope it’s helpful…)

Ah! ” ‘The Object’ is an enigmatic sculpture by legendary design group Hipgnosis en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hipgnosis. It’s featured on Led Zeppelin’s ‘Presence’ en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Presence_(album) album, and this is a 3D printable version.” [ http://vimeo.com/24024599 ]

Darn, do I have to get me one of those 3D printers now?

———————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

The smiling, cheerful normality of the adults and the blank featurelessness of the children, all captured in high focus, suggest a certain feral threat — a hungry falseness.

————————-

“Hungry falseness”; an excellent name for the advertising industry-created appetites for things which turn out to be utterly empty; leaving us craving MORE, MORE…

The fervently eager, mindless, healthy-looking folks in those “Object”-subverted images recall the fervor — for Communism rather than products of Capitalism — herein:

http://news.ucdavis.edu/photos_images/news_images/04-2008/chinese-poster_lg.jpg

http://www.gwarlingo.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/chinese-propaganda-poster-red-book.jpg

If not as foreboding as “the skeleton at the feast,” that black object is certainly unsettling, inexplicable. Makes one think of “the Surrealist Object”:

———————–

It is here within the surreal fusion between dream and reality that the Surrealist object evolved…

Breton understood that the object had been in a state of “crisis” from, as he stated, about 1830 when scientific studies and poetic and artistic experimentations began to develop along parallel courses. On one hand, science studies objects as material things, and on the other hand, the arts manipulated objects for aesthetic purposes…

Surrealist theory sought to re-enchant the universe and thought that the crisis of the object could be overcome if the thing in all its strangeness could be seen as if anew. The strategy was not to make Surreal objects for the sake of shocking the middle class public but to make objects “surreal” by dépayesment or estrangement. The goal was not so much the choice but the hunt and the displacement of the object, removing it from its expected context, which would defamilarize it. Once the object was stranded outside of its normal place, it could be seen without the veil of cultural conventions. …

————————–

Or, in the case of the images in “Presence,” the mundane is transformed by the juxtaposition of an inexplicable, unfamiliar item.

The above quote from http://www.arthistoryunstuffed.com/the-surrealist-object/ ; which goes on to ponder the psychological and political/monetary aspects of the Surrealist Object:

————————–

The Surrealist object was closely related to Freud’s concept of the “fetish.” The ordinary object becomes a fetish because we project our desire upon it, because we look at it and look again until we cannot stop looking. The selection of this object, like any Dada object, is random. And like the Surrealist object, the choice is not as significant as the meaning the human psychology gives to it. The fetish is always a substitute for something else and always has a sexual content, is always a substation for sexual satisfaction. Although not explicitly mentioned, Marx’s commodity fetish not only predates Freud’s sexual fetish but also shares the same cognitive mechanism.

For Marx, the commodity becomes a fetish when it can be exchanged for something else, or acquires a monetary value through its symbolic meaning, which is the “something else” outside and beyond the object itself. In other words, certain objects become commodities because we, the consumer, are willing and able to invest something of emotional selves into the object. Marx was intrigued at how such fetishized objects are exchanged when a concept we translate as “value” becomes monetized. Marx and Freud agreed that whether symbolic commodity or sexual substitution, the fetishized object is never itself and is always the “symptom” for something else. That projection of subconscious desire for an absent entity is what characterizes the Surrealist object. The definition of the object is never a scientific or an objective or a conventional meaning. The symbolic value (meaning) is always personal and subjective to the possessor.

————————-

As we may recall, “Alva Museum Graphics in New York was contracted to produce 1000 individually numbered 12″ tall black Objects for Swan Song to use in their promotion of the record”; that site going on to detail the marketing of “real” and “repro” Objects.

BTW, the album name, “Presence,” has a spiritual dimension:

————————–

– “an invisible spirit felt to be nearby”

– “divine, spiritual or incorporeal being felt as present”

—————————

http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/presence

They predicted our fascination with cell phones, cool.