In his long essay on Darwyn Cooke’s Before Watchmen work, William Leung convincingly, and even devastatingly, portrayed Cooke as a reactionary tool. Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons in Watchmen deliberately set out to undermine and deconstruct the assumptions behind superheroic archetypes and narratives. Cooke, Leung argues, set about reconstructing them. Or as Leung puts it:

Whereas Moore was interested in demolishing heroic stereotypes in order to explore the humanity beneath, Cooke is more interested in reinforcing stereotypes in order to prescribe for humanity what is and isn’t heroic. Under Cooke’s revision, a critique of heroic constructs has reverted to a defence of heroic constructs.

I am entirely convinced by Leung’s argument that Cooke’s Before Watchmen is a vile, steaming pile of shit. I’d like to make a brief case, though, that reconstucting heroic sterotypes isn’t necessarily evil or wrong-headed. Even, possibly, the “heroic power fantasy of heterosexual males”, which Leung sneers at, might in some cases be a force for good.

So if we want to discuss the virtues of reactionary nostalgic heterosexual male power fantasies, we should maybe take our eyes off of Before Watchmen (please God) and look instead at Kurt Busiek and Brent Anderson’s Astro City.

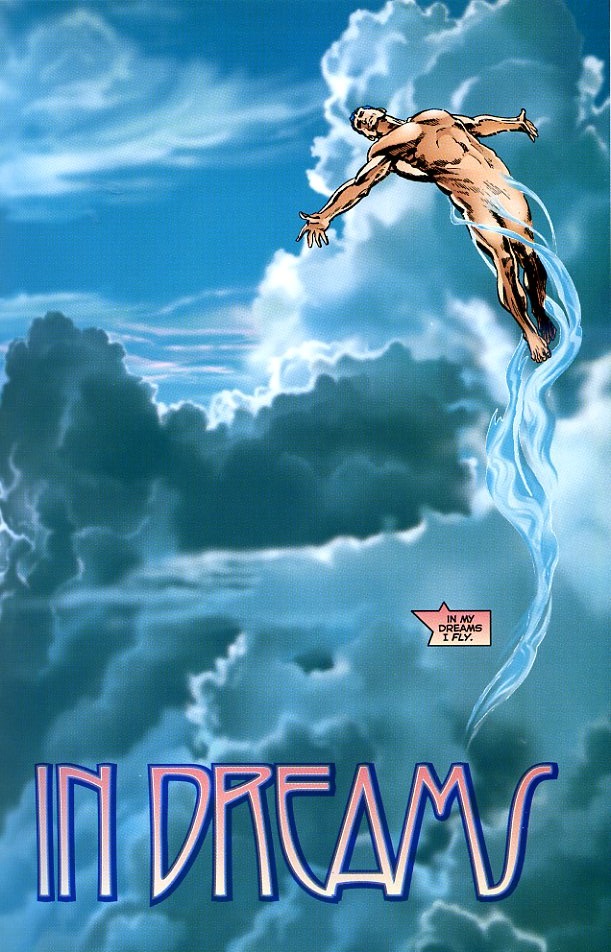

Astro City came out around 1995, it looks like — and I don’t think there’s much question that it’s in conversation, at least partially, to Watchmen. Its reaction is, moreover, like Cooke’s, reactionary. Where Moore and Gibbons show superheroes as damaged, perverse, violent psychopaths with delusions of grandeur, Busiek and Anderson return deliberately, nostalgically, to a mostly unproblematized vision of superheroes as do-gooding power fantasy. You see that from the very first page of the first issue, which presents us with that ur-super fantasy — the dream of flying.

The twist here is that the infantile power fantasy of flight belongs, not to a powerless adolescent or man/boy, but to a superhero — specifically to the Samaritan, Astro City’s Superman analog. Samaritan can actually fly himself — but he’s so busy he doesn’t have time to enjoy it. The adolescent power fantasy is doubled back and turned into an adult de-responsibility fantasy. Instead of the narrative targeting boys who wish they had the power of men, it targets men who wish they were boys. Comics, once offering the promise of larger than life abilities and adventures for children, here become a nostalgic icon of an essentially smaller than life lack of clutter. It’s not the flight that is exciting (Samaritan can fly, after all) but the space to dream about flight. The comic’s first page, in other words, is a dream of a dream — or a dream of a comic. It deliberately charges, or romanticizes, its own comicness.

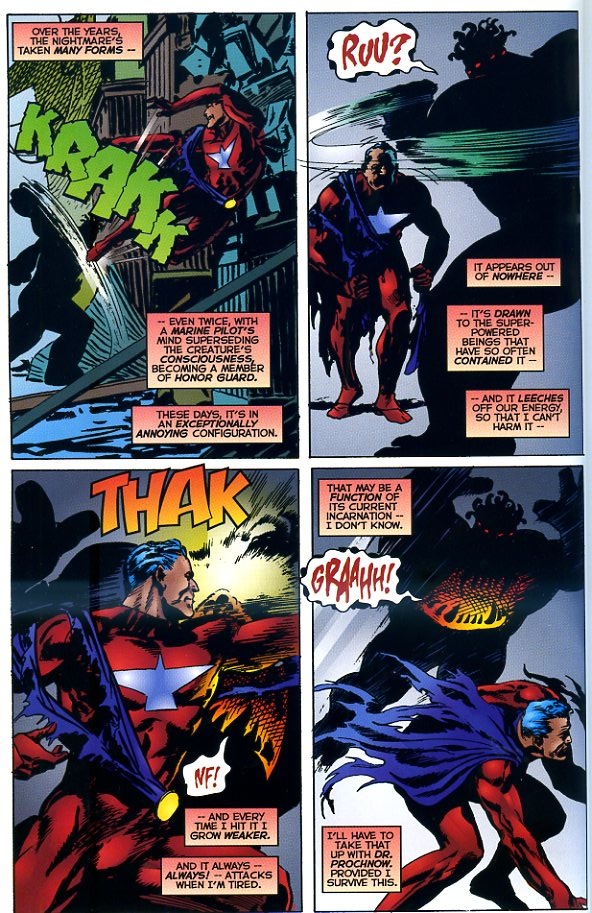

On the one hand, you could say that this remythologizes what Watchmen demythologized. And it does in a way. But it’s a particular kind of remythologizing — one which is very aware, even incessantly aware, of its own mythmaking. Traditional superheroes were exciting and noble. Watchmen’s superheroes were exciting and ugly. Astro City’s superheroes are…boring. Deliberately boring. In this first story about the Samaritan, his adventures have all the kinetic oomph of a 9 to 5 desk job. A lot of the action is described in off-hand text boxes without ever being shown (“pyramid assassins in Turkey and a nasty chronal rift in Stuttgart. A lot of mid-air antics….”) Even when we do see the superstunts, it has an air of anticlimax, as in the battle with the Living Nightmare.

I really like that top right panel; Samaritan is supposed to be ducking, but he ends up just looking old and bent; some middle aged guy in a funny suit waiting for the super-villain bus. And then, in the final text block, he’s making mental notes for himself about how he’s going to have to consult a doctor “provided I survive this.”

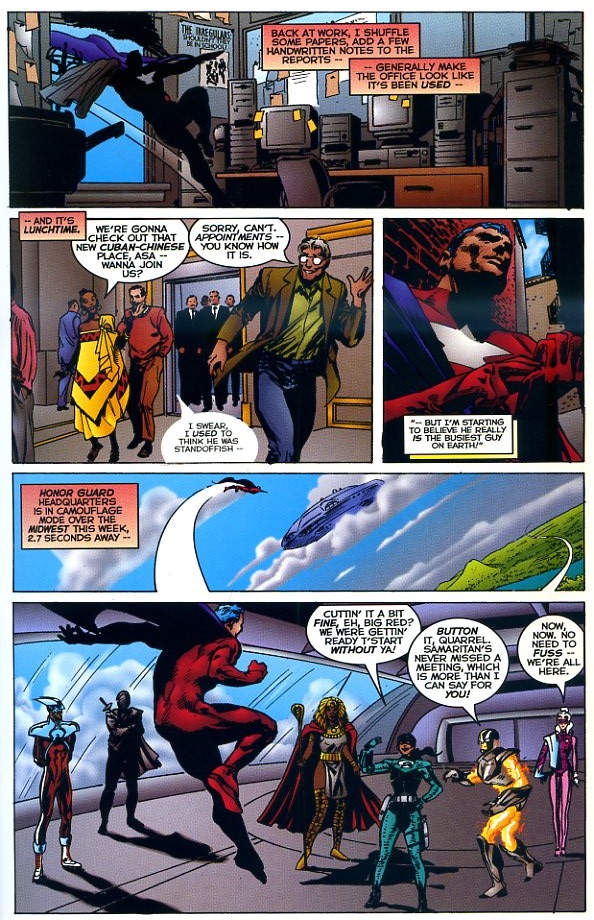

In fact, in comparison to the low-key narrated super-heroics, it’s only the 9 to 5 desk job which comes alive. The Samaritan’s secret identity, Asa, works as a fact checker, and when he does, he actually gets to talk to people. The office chit chat seems much more real than the weirdly distanced superheroics…except for those moments when the weirdly distanced superheroics start to sound like office chit chat, as in the bottom panel here.

Unsurprisingly, Samaritan is as disconnected from his sexuality as from his dreams of freedom. Busiek and Anderson show him fact checking a story about the city’s most beautiful women, and eating his heart out because he has no time for romance in his life. We’ve gone from the sexlessness of adolescent power fantasies to Watchmen’s twisted sexuality to a sexlessness not of innocence, but of getting older and just not having a whole lot of time.

Samaritan’s heroism, his goodness, starts, then, to look like the heroism, or goodness, of going in to work and doing a job. It’s heroism as middle-aged slog; all responsibility, no fun at all.

So traditional superhero narratives show how cool it is to be a man and save everyone. Watchmen deconstructs that by showing how the desire to be a superman and save everybody is ridiculous, perverse, and dangerous. Busiek and Anderson reject Watchmen’s dour vision, and reconstruct superheroism — but with a twist. The manliness they present is a fantasy in many ways of seflessness and disempowerment. The real superhero is good, because the real superhero has no power. Comics fantasy becomes, not a pattern of dangerously empowered masculinity, but a kind of nostalgic safety valve — the dream of childishness that lets daddy be a good daddy. Superheroes become a strategy, not of validating power, but of subordinating the powerful to the good.

Busiek and Anderson’s vision of masculinity is both traditional and reactionary. Samaritan is man as responsible caretaker; boring father as heroic non-entity. No doubt Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons had a point when they suggested via the Comedian/Dr. Manhattan/Ozymandias that these uber-daddy fantasies involve megalomania and other unpleasantness. But, on the other hand, is an unhinged mass murderer really more real or true in some absolute sense than a guy with a day job? Samaritan’s dreams of flying my be unreal and even silly, but on behalf of boring father’s everywhere, I wonder if that really has to be such a bad thing.

Here’s a quote from Busiek on what he was doing in terms of reconstruction:

“KB: Yeah, Watchmen, Dark Knight, and various others set off and age of deconstruction. Everybody was concerned with pulling apart the superhero, its absurdities and its insanities. And, to my mind, to deconstruct something it to take it apart to see how it works so that you can put it back together again — and then take it out on the highway and see what you can do with it. So, when I did Marvels and then later with Astro City, my concern was with doing reconstruction: with taking all the lessons learned from deconstruction and putting the engine back together, seeing how to make it run even better. There were other people, consciously or unconsciously, very involved in that —- Mark Waid, Karl Kesel, Scott McCloud, for instance.”

http://www.popmatters.com/pm/review/interview-busiek3/

Thanks Pallas!

Thanks for this.

I am going to bust out the issue of AC where the cartoon lion comes to life and ends up a pedophile (or something like that). I have not read it in over 10 years, but I seem to remember it being pretty twisted and ripe for analysis.

I also need to re-read the Dark Age stuff now that it is finally all out. . . at the time reading it piecemeal I was pretty disappointed with it, as I couldn’t see what it was really accomplishing in terms of its take on the Bronze Age.

Hmmm…I don’t think I have either of those. I’ve got the first couple Astro City collections, which I quite enjoyed, but never got around to reading any more…

It does kind of go downhill after awhile I only made it halfway through Dark Age… but it’s certainly better than almost (?) any of the big 2’s superhero output.

Well, that’s definitely damning with faint praise at this point…

” I am going to bust out the issue of AC where the cartoon lion comes to life and ends up a pedophile (or something like that). I have not read it in over 10 years, but I seem to remember it being pretty twisted and ripe for analysis. ”

You’re correct, Looney Leo slept with a hooker who turned out to be fourteen (though she told him she was legal). She fatally overdosed that night as well, which ruined what was left of Leo’s career (with the prostitute’s abusive mother leading the charge against him, clearly trying to milk as much publicity out of the tragedy she helped cause).

Of course, this was all handled with surprising sensitivity, with Leo mourning her loss and reflecting on his own culpability years later (something to the effect of “I may not have stuck the needle in her arm, but I didn’t exactly try to stop her”)

Thank you for a wonderful analysis of one of my favourite Astro City stories. I’ve intermittently dreamed of flying, as have many of my friends I’ve talked to, so it was very refreshing to see that idea through the lens of a superhero who can actually fly.

What I love about Astro City is that it does a great job of using superhero tropes not as an end unto itself, but to explore very resonant themes. The heroes of Astro City do go on adventures and fight villains and crime, but the story at the heart is always about more than that.

I really liked the Confession and Tarnished Angel collections and how it handled the themes of integrity and legacy, and I’m interested to know what your views are on those.

A provocative reading, Noah; I read two collections about ten (!) years ago and found them boring and banal. It never occurred to me to recast that as a virtue — but, even after this, I’m not convinced I should. Still, at least it’s not Kingdom Come.

It might be fruitful to compare the book with Gandalf’s own efforts at reconstruction, which comprised a lot of his output for about fifteen years, starting in the early 90s: 1963, Supreme, Judgement Day, Youngblood, through to the America’s Best Comics line. Most of these are unapologetically fun and thematically shallow (not a bad thing!), seemingly meant just to entertain the punters (again, not a bad thing). To me, the most interesting comparison is with Top 10, which very overtly positions superpowers as just another day at the office. But he seems now to have backed away from reconstruction with the useless, unheroic flounderings of the League.

I definitely think the low-keyness of Astro City is the thing. At least in that first volume, it really does just aggressively refuses to put the superheroics front and center. All the action; you know about that from reading other comics books, and then it sort of occupies the space in your life that it actually does when it’s just a thing you read off to the side in comic books.

In that sense, I think it is more imaginative and unconventional than Moore’s later fun efforts. I generally like those, but they do try to reproduce the goofiness of the silver age, rather than presenting a world in which the goofiness of the silver age is as banal as reading a comic book.

Aaron, I may look at what else I’ve got about and do another Astro City piece…it seems like not very many people have written about them? Is that true?

I think that since it’s a fairly old series, there hasn’t been a lot of current writing about it. The online comics community has grown a lot, but so has the amount of comment-worthy comics (IMO). I feel like Astro City and Top Ten do mine some of the same space in using classic superhero tropes to tell different stories, and both were somewhat under-appreciated.

I agree with Eric about the later stuff- it just got caught up too much in its comicness- The Dark Age seemed more interesting in focusing on doing a pastiche of every 70s comic rather than focusing on the main characters and their tale, though I never finished it.

It’s one of the few superhero comics I can stand. I pretty much agree with your take on Samaritan as Superdad, but Busiek examine many other character archetypes in different ways. And things do get darker (though not idealized) in The Dark Age.

You’re also right that for the most part, Busiek deliberately (almost perversely) shelves the action stuff in favor of the character stuff. This is not surprising; he was quoted as saying that he sometimes wasn’t so much interested in what Superman was doing as he was in the guy who said, “Look, up in the sky!” What was that guy’s story, what was it like for him to live in Metropolis? Which you either think is boring or interesting, but I like the countless variations Busiek has on Observer Stories.

And quite honestly, his “The Nearness of You” is one of my all-time favorite superhero stories. It’s about a lonely man haunted by dreams of a woman he’s never met; eventually, it’s revealed to him that she was erased in some giant reality-spanning war. He’s given the opportunity to have her memory erased from his mind, but he chooses not to. Very simple, just 10 pages or so, but Busiek’s attention to detail earns its emotional pull.

What I love about “The Nearness of You” (aside from the pathos, of course) is that it effectively demonstrates that what would be a 10-issue crossover jerkfest in either of the Big Two can be made to fit in a 10-page story as background without having to get ridiculous about it.

My fave stories feature the Mock Turtle.

Perhaps because I’ve always rooted for the typical Brit silly underdog, perhaps because of the mingled sadness and comedy. And with a tragic ending, of course.

Overall this series has never had the respect it deserves, compared to “Marvels”, “Kingdom Come” or even (dare I say it!) “Watchmen”, works mining the same vein.

Mock Turtle was just in two issues, right? One featuring him which had a happy ending, then in the next issue you find out he was killed off panel between issues?

That was good stuff.