In her 2002 essay Comparative Sapphism (recently made available for download, my friend and colleague Sharon Marcus contrasts the place of lesbianism within 19th century French literature and 19th century English literature. In simplest terms, that difference is one of presence and absence.French writers include lesbian themes, characters, and plots; English ones, by and large don’t. As Sharon demonstrates with a fair amount of hilarity, this posed a problem for English reviewers of French books, who somehow had to talk about lesbianism without talking about lesbianism — resulting in the spectacle of intelligent cultured reviewers demonstrating at great length that they knew the thing they would not talk about, and/or didn’t know the thing they would.

What’s most interesting about this division, as Sharon says, is that it ultimately isn’t about attitudes towards lesbianism. It’s true that the English back then didn’t like lesbians…but the French back then didn’t like lesbians either. Everyone on either side of the channel was united in a happy cross-channel amity of homophobia. So, if they hated and hated alike, why did the French write about lesbians and the British didn’t? Not because the first liked gay people — but rather because the first liked realism.

Since French sapphism was fully compatible with anti-lesbian sentiment, and since Victorian England easily rivaled its neighbor across the Channel in its homophobia, we cannot explain the divergence between British and French literature solely in terms of the two nations’ different attitudes to homosexuality. Rather, any explanation of their sapphic differences must also compare the two nations’ aesthetic tendencies. Such a comparison suggests that there would have been more lesbianism in the British novel if there had been more realism and that British critics would have been more capable of commenting on French sapphism had they not been such thoroughgoing idealists.

In other words, the French saw portrayals of lesbianism as part of the seamy, ugly, realist underbelly of life — and they wanted to show that seamy underbelly because they thought realism was cool and worthwhile. The British also saw lesbianism as part of the seamy underbelly of life — but since they were idealists, they felt that literature should gloss over such underbellies in the interest of setting a higher tone and generally leading us onto virtue.

One interesting point here is that everybody — French and British — appears to agree not just on the ickiness of lesbianism, but on its realism. Which means, it seems like, that the French might discuss lesbianism not merely because they are comfortable with realism, but as a way to underline, or validate, their realism. That is, lesbianism in French literature serves the same purpose that grime and “fuck” and drug dealing and people dying serve in The Wire. It’s the traumatic, ugly sign of the traumatic, ugly real.

Nor were the French the last to use queerness in this way. Watchmen, Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons 1980s exercise in superhero realism, does much the same thing.

This isn’t to say that Watchmen is homophobic; on the contrary, Alan Moore in particular is, and has long been, very consciously and ideologically queer positive. But it’s undeniably the case that Watchmen‘s goal is, in part, to imagine what superheroes would be like if they were grimy and seamy and nasty and real. And part of the way it imagines superheroes as being grimy and seamy and nasty and real is by imagining them as sexual — particularly as perversely sexual, which often means queer. Indeed, the first superhero, who inspired all the others, is Hooded Justice, a gay man who gets off on beating up bad guys. Thus, the founding baseline reality of superheroics is not clean manly altrusim, but queer masculine sadism.

Incipient buttcrack, bloody nose, homosexuality. You don’t get much more real than that.

The hints of homophobia in Moore/Gibbons, then, seem like they’re tied not (or not only) to unexamined stereotype, as my brother Eric suggests. Rather, they’re a function of the book’s realist genre tropes.

Which perhaps explains why Darwyn Cooke, infinitely dumber than Moore and Gibbons, ended up, in his Before Watchmen work, with such a virulent homophobia. William Leung in that linked article suggests that the homophobia is part of Cooke’s retrograde nostalgic conservatissm — which is probably true to some extent. But it’s probably more directly tied to Cooke’s effort to match or exceed Moore/Gibbons’ realism. Portraying gay characters as seamy and despicable is a means of showing ones’ unflinching grasp of truth. In this case, again, realism does not allow for the portrayal of homosexuals so much as (homophobic) portrayals of homosexuals creates realism.

In the discussion of superhero comics, generally allegations of retrograde political content go hand in hand with allegations of escapism. Superhero comics are “adolescent power fantasies,” which is to say that they’re both unrealistic and mired in violence and hierarchy. The link between realism and homophobia, both past and present, though, suggests that when you take the opposite of adolescent power fantasies, you get adult disempowerment realities. And the groups disempowered often turn out (in keeping with realism) to be those which have traditionally been marginalized and disempowered in the first place.

In that context, I thought it might be interesting to look briefly at this image that was following me around on Pepsi billboards in San Francisco when I was there last week.

Obviously that’s Beyonce. Less obviously it’s basically a comic — the character images are repeated in a single space to suggest time passing or movement. And, perhaps, least obviously, it’s fairly deliberately referencing queerness. Beyonce often looks like a female impersonator, but the aggressively blond hair and the exaggerated flirty facial expressions here turn this image into a quintessence of camp. Also, note the position of her hands; one hovering around crotch level on her double, the others behind the butt. Gender, sexuality, and identity are all labile, and the lability is the source of the picture’s excitement and energy, as well as of its deliberate and related un-realism. Rather than queerness being the revealed and seamy underbelly of truth, in this image it’s a winking fantasy of multiplying, sexy masquerade and empowerment.

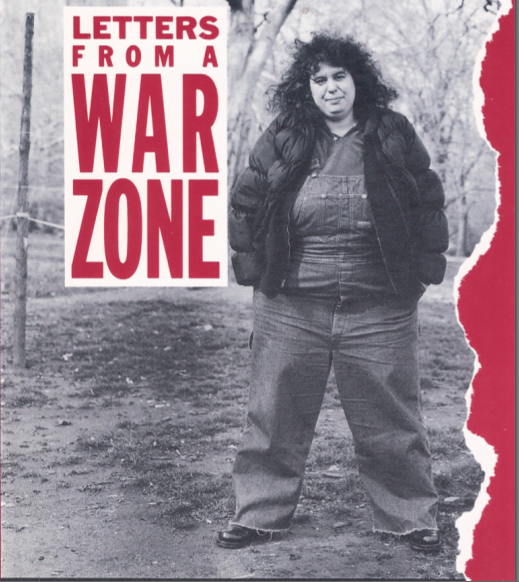

The entanglement of homophobia and realism may help to explain in part why gay culture — faced with tropes defining homosexuality as a sordid ugly truth — has often gravitated to artificiality, camp, and the empowerment of self-created surfaces. None of which is to say, of course, that realism must be always and everywhere homophobic. As an example, I give you…Andrea Dworkin in overalls.

Hooded Justice and Beyonce just wish they were that ugly, solid, real, and awesome.

Been a long time since I read Watchmen, so I could be wrong, but is there evidence beyond Comedian’s quip that Hooded Justice “gets off on beating up bad guys”????

I always read the scene as just showing Hooded Justice is secretly gay. Comedian is the one associating that with sadism. That doesn’t mean it’s true. Hooded Justice is shocked because Comedian knows he is gay, not because Comedian has presented an objective account of his sexuality.

Of course there’s also evidence in the book that all the heroes get off on beating up bad guys during that scene where Silk Spectre and Night Owl are attacked in the alley- but that doesn’t make it associated with homosexuality or heterosexuality, per see.

I suppose that’s a reasonable reading. HJ’s reaction though suggested to me that it Eddie had gotten it right — especially as you say since other superheroes get off on beating up the bad guys.

Also, immediately after that scene, HJ treats Sally like crap (“for god’s sake cover yourself”), showing a discomfort with female sexuality linked both to cruelty and to his homosexuality.

Like I said, I don’t think Watchmen is incredibly homophobic or anything. There are traces though…and they seem to be in part about the realist tropes Moore is using, rather than about any animus per se on his part.

But there’s no other place where HJ is said to be gay. That’s your reading. Comedian is saying that HJ is a sadist, not necessarily a gay one.

Also, French tolerance of homosexuality was far greater, culturally and legally, than was the case in England. Homosexuality has been legal in France since 1803, in England since 1966.

“for god’s sake cover yourself”), showing a discomfort with female sexuality linked both to cruelty and to his homosexuality”

“For god’s sake cover yourself” can be read as a sign of the times- the scene is set pre feminist movement after all. Hooded Justice gets very few lines or development in the series, so it’s pretty ambiguous.

Yeah, it’s the kind of line even heterosexual assholes could say even today.

Not sure what you’re talking about Alex; there are refs to HJ being gay in several places. Hollis makes a not very subtle ref to him and CM at some point, I remember. Cooke may have done a lot of stupid things, but he certainly wasn’t making that up.

And the fact that heterosexual assholes could say it is somewhat beside the point when it comes immediately after Eddie accusing him of being gay and a sadist.

“And the fact that heterosexual assholes could say it is somewhat beside the point when it comes immediately after Eddie accusing him of being gay and a sadist.”

What a weird reading. If Hooded Justice kissed his boyfriend and then ate a hamburger, would see you say that Homeosexuality had been linked to Hamburger eating?

I don’t really see an inference between the two things due to one occurring after the other, personally.

If Eddie said, “you dirty homosexuals, always eating hamburgers,” and then we saw a picture of HJ and CM eating hamburgers together, then yes, I’d say that the two things had been linked.

Eddie didn’t accuse Hooded Justice of being uncomfortable with female sexuality, nor did he say “You gays, always slut shaming women!” so your hamburger response seems a real stretch.

He accuses him of being a gay sadist. Then we see him being uncomfortable with female sexuality and acting brutally.

I don’t really see it as a particularly subtle or abstruse reading.

A quick search of google books of the phrase Watchmen “Cover yourself” shows an author writing:

“Both the Comedian and Hooded Justice represent the misguided perception that women are responsible for being raped if they dress provocatively”

This is from Watchmen and Philosophy: A Rorschach Test

The Reading Watchmen web site says:

“Watchmen: Chapter II – page 8

PAGE 8

“Panel 1: The remark by Hooded Justice to Sally, “And, for God’s sake, cover yourself.” would have been a typical comment of the time. This remark also transitions nicely into

Panel 2: where we are looking at a scene from Sally Jupiter’s Tijuana bible, an ironic juxtaposition of two ways in which women’s sexuality is disrespected.”‘

So I think there’s evidence to suggest that your reading is quirky and also it’s odd that you ignore the juxtaposition with Page 8 panel 2 if it follows that something following something is such a big deal to you.

Apparently page 8 panel 2 suggests the line is broad social commentary.

Another annotation states Sally blames herself for the rape in a later interview sequence- which dovtails nicely about a general social commentary rather that commentary on Hooded Justice in particular.

How is my reading quirky because other people have different readings which in no way contradict mine?

Really, nothing I say is contradicted by anything you write there. And in fact, I don’t disagree with any of those other interpretations. So…can we agree to agree?

I mean…I guess it could be quirky in that no one has said it (or at least, you haven’t found anyone who’s said it.) But since it isn’t contradicted by what people have said, I don’t really see why it’s invalidated.

While it’s possible Moore intended both readings, I think its more likely he intended just the readings highlighted in the annotation, the more typical reading, which explains why the “cover yourself” line was included in Watchmen.

You seem to think he intended both readings. We’ll have to agree to disagree.

I’m not especially concerned with intent per se….

I do think that one of the pretty obvious readings of HJ telling Sally to cover herself is that it shows that, despite their supposed public relationship, he doesn’t actually care about her. Which means that the line underlines his homosexuality, as well as the general misogynist attitude of the time.

That’s how I read it on my first reading of the comic, when I was in high school and hadn’t read a ton of queer theory. Again, I don’t think it’s especially abstruse.

Noah:

“He accuses him of being a gay sadist. Then we see him being uncomfortable with female sexuality and acting brutally.”

No, Eddie doesnt accuse him of being a GAY sadist, but of being a sadist. Many sadists are gender-neutral in their preferred “victims” (scare quotes because the latter are often consenting. S&M, eh?)

As for the “cover yourself” line:

Here HJ is confronted with the battered and bleeding, violated body of a shattered, suffering woman.

As a sadist, wouldn’t he be stimulated?

As a sadist in denial, wouldn’t he be horrified?

(I’ve little doubt he IS in denial, the speed with which he let Eddie go testifies to this. I think HJ was a sadist who found an acceptable release in super-heroics.)

Thus, “for God’s sake” — almost a panicky remark.

I’ll stress that Noah’s reading isn’t inferior to mine, but it isn’t superior, either.

And in fact, a work’s ability to elicit multiple readings is probably a sign of its richness and complexity.

Ironically, though, in this case Noah’s reading of HJ coincides perfectly with Cooke’s…

Well, that’s kind of my point in the piece. That is, Cooke’s linking of homosexuality and sadism as a way to make the comic more real is something that is in the original too (though much muted.)

And…he is horrified by Sally’s state, or seems to be disturbed by it…? You seem to be offering an expansion on my reading rather than a contradiction to it…?

Well, no, I think he is aroused by her state, sexually and sadistically (if the two can be distinguished) before his superego cuts in.

Well…that works with my argument that he’s uncomfortable, right?

Oh sure, but in a general way. I don’t read it as his being uncomfortable with female sexuality, but rather with his own sadistic urges.

Mind you, both may obtain.

Yeah…I guess it is a somewhat different slant. As you say, they’re not exclusive.

The guy is wearing a hood and a noose. Does nobody else see that as a masochistic gesture? He may be a catcher rather than a pitcher.

In the original books, Sallys manager mentiones Hooded Justice sadistic abuse of young men.

Watchmen isn’t just the comic but also those text pieces, which hint pretty strongly that HJ and Captain Metropolis are a couple, and that the Minutemen are consciously hypocritical in expelling the Silhouette for being a lesbian, and add to the suggestions in the comic that HJ is a brutal sadist while Metropolis is his effeminate, ineffectual partner. These aspects of their characters are portrayed negatively, as ways they fail to live up to their heroic personae in this “realist,” gritty treatment. Now, if Cooke is able to treat the Comedian sympathetically there’s no reason he couldn’t have rounded those two out a little. Instead, he amplifies those themes and treats the characters with undisguised contempt. But he is still elaborating on themes that are there. Leung is convincing about Cooke’s dreadful Minutemen comic but strained in his justifications for Moore’s Watchmen, which does use homosexuality as a signifier for gritty realism as Noah says and has a really problematic storyline about the two main female characters learning to love and accept a rapist. Again, Watchmen is not just the comic but also the text pieces; not just that page where Laurie declares her intention to adopt a version of the Comedian’s costume and Sally plants a kiss on his photograph, but also that passage in Sally’s interview where she talks about how she can’t blame him because she might have been leading him on. Yes, Moore has taken feminist and gay-positive stances, but those don’t change or justify his negative portrayals of homosexuality or his strange treatment of violence against women in Watchmen, V for Vendetta, the Killing Joke, and Neonomicon.

“also that passage in Sally’s interview where she talks about how she can’t blame him because she might have been leading him on”

I don’t think that’s meant to be Moore’s view. That is, I don’t think the comic presents it as Sally leading him on. I think that passage suggests that Sally is conflicted and confused, not that anything she did actually justified the rape.

The treatment of violence in women in V is really problematic. I agree with that.

I love Watchmen, incidentally. It’s one of my favorite comics. That doesn’t mean it’s perfect in every way though….

I haven’t read Watchmen in a while. It is an interesting choice to give a sadist a mask and a collar and then expose him as insecure.

Here’s the quote from Sally Jupiter’s interview in Watchmen:

“You know, rape is rape and there’s no excuses for it, absolutely none, but for me, I felt… I felt like I’d contributed in some way. I really felt that, that I was somehow as much to blame for… for letting myself be his victim, not in a physical sense, but… but it’s like, what if, y’know? What if, just for a moment, maybe I really did want… I mean, that doesn’t excuse him, doesn’t excuse either of us…”

This selection is repeated and runs in big, boldface letters, magazine style:

“You know rape is rape and there’s no excuse for it, absolutely none, but for me, I felt… I felt like I’d contributed in some way.”

I’ve only just read this, but I remember reading Marcus’s original discussion of Sapphism in 19th century British and French literature. It just occurred to me, though, that perhaps the French included Sapphism in their literature not only because they were more comfortable with realism, but also with sex in general. The Victorians were so repressed they coyly alluded to heterosexual sex, let alone lesbianism. The French have always been more open and comfortable with sexuality–they gave us terms such as “menage a trois,” after all.