This first ran on Splice Today.

______________

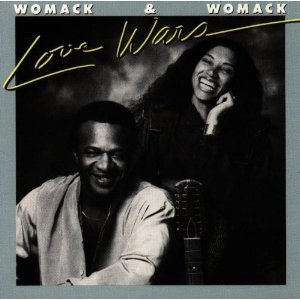

“Love wars, no more love wars,” the chorus sings at the beginning of Womack & Womack ‘s 1983 debut. Explicit appeals to non-violence are notably rare in American popular culture, but if they make sense on any album, it’s this one. Cecil Womack (Bobby’s brother) and his wife Linda (Sam Cooke’s daughter) make R&B music not just for the middle-aged, but for the middle-aged with no mid-life crisis, thank you. Neither quite soul nor quite funk, Love Wars sits somewhere between the two, the songs blending one into another in a mélange of repetitive but not-too-urgent vocals and repetitive-but-not-too-urgent hooks, expressing easy relationship tension and easy relationship bliss in equally measured doses. When Linda declares, “Baby I’m Scared of You,” she doesn’t sound all that scared; when Cecil declares he can “really turn your lovin’ on,” he doesn’t necessarily sound like he needs to do so — a point emphasized by Linda’s (moderately) sassy response, “I can’t understand that baby.”

I’m sure for some folks, that all sounds dreadful — but for me, the self-effacing low key approach is definitely a feature, not a bug. For fairly obvious commercial reasons, pop and soul have always found it easier to do sweeping hyperbole than understatement; everybody likes melodrama, after all, with its big lows and big highs. If you’ve been unlucky in love, then you’re going to drown in your own tears and/or declare with stentorian vigor that you will survive.

But if Ray and Gloria are out there loving and losing with hearts out on their sleeve and up a flag-pole and blaring from loud-speakers, the Womacks are here to tell you that relationship drama can be quiet and boring too. “I got my do’s/and I got my don’t’s/you ain’t for real and I’m sure I won’t/a woman’s got to play it safe,” Linda sings in “Catch and Don’t Look Back,” explaining why she’s not falling for a player’s line. The whole song is about how nothing is happening. The music struts along, the funk undergirding a sweet, almost wistful melody, and you can almost miss the emotional center, where she mentions off-hand that she’s been burned before. There’s no catharsis; it’s not even clear whether we’re supposed to be happy or sad for her. Is she smarter and stronger or just damaged? The groove shrugs its shoulders like Linda musing, “oh, I’m hip to that.”

Cecil provides the same kind of smaller-than-life lament from the guy’s perspective. What other performers would compare a failed relationship, not to a knock-out, but to a “T.K.O.”? His light, raspy vocals drift over the slow-boiling backing, fitting the half-hearted aimlessness of the lyrics. “I think I better let her go,” he muses, before spiraling up into a falsetto yodel that bizarrely imitates one of those 80s smooth sax solos, as if the ambivalence of his predicament has actually physically transmuted him into soulless cheese.

I wouldn’t say that the low-stakes approach always works for the Womacks. Turning Mick Jagger’s exhausted dead-end “Angie” into a softly lilting chat between mildly discomfited lovers probably wasn’t such a great idea, for example. But then there’s the album closer, “Good Times,” a declaration of mutual love that includes the hilariously mild praise, “you’re not as bad as you make out to be.” The real message, though is in the harmonizing; Linda starts the song off with a series of “la-la-las,” and as she winds down, Cecil comes in with a stuttering counterpoint. It’s lovely and awkward and right. Passion and world-shattering love are appealing, of course, but I think for most of us middle-aged folks, the ideal is probably closer to what Womack and Womack offer here: a vision of two as one gracefully bumbling whole.