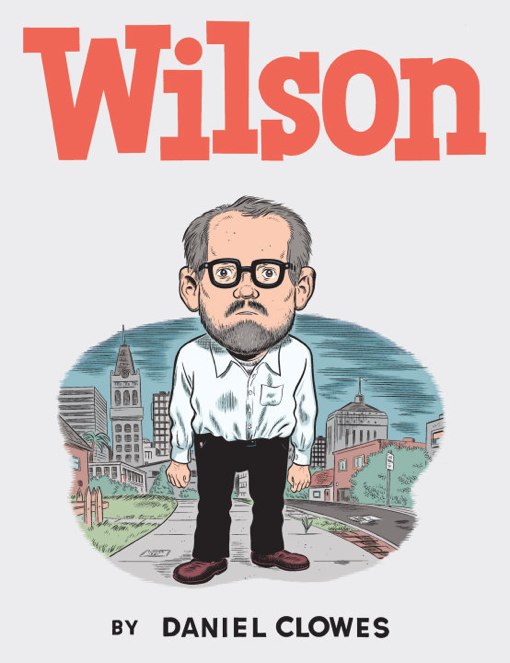

Peter Sattler wrote a great comment about Dan Clowes’ Wilson and the oppressive weight of comics. So I thought I’d reprint it below.

I had never thought much about linking gender and comics per se in Clowes’ work, but you make a strong case, especially for Velvet Glove.

Over the years, I have only presented a few papers that touch on Clowes, usually in the context of broader claims. But I tend to agree with you that his work goes out of its way to thematize the artist’s and/or the story’s struggle against comics themselves – against a form that, as Clowes presents it, seems unable to encompass interior states, unable to escape its own theatricality and artificiality, unable to circumvent its own closed system of beginnings and endings, set-ups and punch-lines. Clowes dramatizes his contest with these limits, transforming that contest into the content of his graphic novels.

Take Wilson, for example. The sense of connection, of understanding, of interiority, of history that the Clowes’ characters – mainly, Wilson – repeatedly say that they want are always thwarted by the protagonist’s unwillingness to stop talking, by his demand that other people – especially women – shut up. It would be easy to see this as a feature of Clowes’ misanthropic creation: a man too horrifically self-involved to see his own villainy. But on the page itself, this solipsism is most visibly as a series of qualities endemic to comics: the obscuring and endless series of word balloons; the need to keep talking, running an externalized and insuperable inner monologue; the infantilizing and ironizing iconography; the truncated and isolating nature of the comics page itself (and few long-form cartoonists seems as wedded to the idea of comics as a collection of discrete pages as Clowes).

Indeed, it is the rigid nature of the page – imposing its own unavoidable sense of beginnings and endings – that most circumscribes Wilson’s exploration of human connection and meaning. At least in this volume, no matter what one says or sees, the ultimate reality is that any particular page must come to an end, must toss the reader back outside the work, and must, to some extent, deflate anything that might count as narrative. No matter what one encounters in the middle of the strip, it must always end when the page and its panels run out. For Wilson, this means ending with a joke. But in Clowes’ world, the deflationary punch-line and the structure of the Sunday funnies are just shorthand for the fragmented, one-page-at-a-time and one-damn-page-after-another nature of comics overall.

In Wilson, it is comics that keeps you talking, and it is comics – at least as Clowes represents them – that shuts you up. The form of comics lends its stamp to the structures of your thought (“Insert ass-rape joke here”) and to, it seems, how Clowes can represent — or not represent — thinking. (At last year’s conference at the University of Chicago, Clowes told the audience that he now tends to experience his own life in one-page segments.) I’m not trying to say that Clowes hates comics, of course; he clearly loves them. But as much as anything, he seems to be infatuated with the conflict that he has with the medium – with its history (or you argue, Noah) and with its historically inflected structure.

The most common last-panel punch-lines in Wilson involve excrement, and three different times those joke involves shit that is boxed and mailed. Perhaps that is the ultimately stand in for what comics can give you. That final delivery always comes, promising a special message. But it always comes out as dog poop.