Optic Nerve #13 by Adrian Tomine (Drawn & Quarterly)

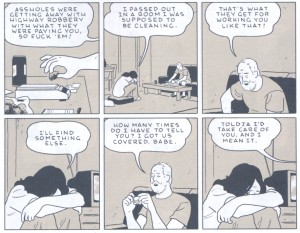

In his previous issue of Optic Nerve, Tomine seemed to be playing around with stylistic tics borrowed from Frank King and Dan Clowes. In the main story of the current issue, “Go Owls,” Tomine does some very assured drawing and storytelling in a naturalistic mode that in this case is a little reminiscent of Jaime Hernandez. But there is no doubt, he is his own man and he is getting better all the time. Here the artist breaks significantly away from his previous stories that dealt more with educated young urbanites to depict the relationship beween a Middle-American, more proletariat couple who meet in a recovery program. Reading it, I felt as if I knew them.

The guy is an asshole, but Tomine manages to show that without hammering the point; he enables his story to unfold in a quite believable manner and elicit sympathy where he wants it directed with subtlety. The use of varying colors in a very limited palette throughout works nicely and is balanced by the exquisite control shown in the full color story in the back of the book, which also displays the high level of skill and delicacy that Tomine is growing into with his art.

_____________________________________________________________

The Daniel Clowes Reader, edited by Ken Parille (Fantagraphics)

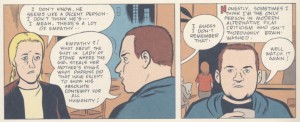

This fascinating collection of some of Clowes’ best works is published in the form of a teaching guide, copiously annotated to the nearly absurd degree of including subglossaries defining miniscule details hidden in the author’s panels. In this way, editor Ken Parille begins to resemble Kinbote, the deranged poetry afficianado from Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire, whose notes that introduce and permeate the posthumous edition of his idol/victim’s supposed masterwork begin to entirely supplant the work that they are supposed to supplement. It caused me to Google Parille to try to find out if he is real, or if he is an alter ego of Clowes himself. But, Parille apparently exists in his own right and while I might have chosen a few different stories if I had assembled this book, much of it is admittedly essential and well-served by the package.

The collection includes the entirety of Ghost World, such seminal stories as “Like a Weed, Joe” along with relevant essays and commentary by sundry credible sources, plus Clowes’ excellent polemical pamphlet Modern Cartoonist and another of my favorite pieces of his, reprinted for the first time from Zadie Smith’s groundbreaking 2007 comics/prose anthology The Book of Other People: the brilliant color short “Justin M. Damiano,” a classic that needs to be read by anyone who writes criticism on the internet.

_____________________________________________________________

TEOTFW (The End of the Fucking World) by Charles Forsman (Fantagraphics)

Forsman’s epic minicomics series is collected into a small, thick trade paperback that I’d prefer was fully titled on the cover, rather than intialized as it is. The story resembles the real-life 1958 murder spree by Charlie Starkweather and Caril Ann Fugate, but transposed to modern times and with the gender balance in terms of sociopathy debatably reversed. Forsman’s pair of nihilists are shown to be the results of terrible parenting and are so estranged from human society that they have difficulty feeling emotions and pursuing a viable relationship together, much less to recognise when other people are not psychopaths.

Forsman, a graduate of Vermont’s Center for Cartoon Studies, has a solid grasp of comics storytelling and his lightly drawn page compositions display an intriguing degree of variety. I’d imagine that this would have read in a much more disconnected way in serialized, episodic form; collected, the book reads smoothly and quickly.

_____________________________________________________________

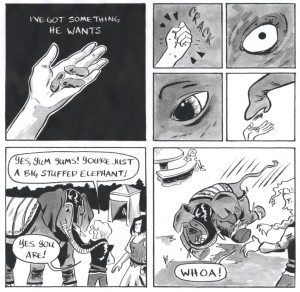

Avery Fatbottom by Jen Vaughn (Monkeybrain)

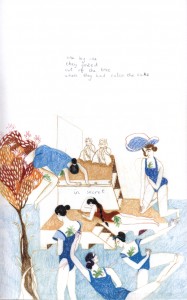

To my mind, a good thing is that so many of the young cartoonists now emerging reject the contrived plasticity of technique and assembly-line methodology that defines contemporary mainstream comics to instead employ an auteuristic, handmade aesthetic in their work. This can be seen in the work of the cartoonists coming out of comics-oriented schools like that of the Center for Cartoon Studies. Another alumni of that program is Vaughn, who displays a breezy, humorous delivery for her comic Avery Fatbottom, a story of young renaissance fairgoers, which is expressively drawn with loose, appealing brushwork, handlettering and organic watercolor halftones.

Vaughn’s romantic sensibility does not take itself overly seriously and so, her evident pleasure in making her comics has an infectious quality. As with the works of Forsman, these efforts cause those who read them to also want to do their own comics, which is pretty much how I got into this game myself.

_____________________________________________________________

The Outliers by Erik T. Johnson (Alternative)

This comic, the first of a series which apparently is the result of a successful Kickstarter campaign (a large group of contributors are thanked in descending order of generosity inside), has some elaborate production values. It is a small square-bound “floppy” that is printed in two colors, including blue and a sort of lime green that gives it the look of a tract.

The cover is comprised of sketches of alien-appearing creatures surrounded by squiggly lines and printed with silver ink on black paper, but one doesn’t notice this immediately because it is wrapped in a somewhat undersized full-color dustjacket. The story within has a sort of adolescent breathlessness and the art is brushy and dense while also suitably organic and (mostly) handlettered, as befitting a semi-underground coming-of-age fantasy comic featuring a Bigfootish monster.

_____________________________________________________________

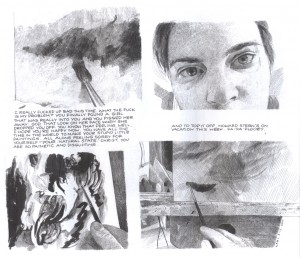

Failure by Karl Stevens (Alternative)

Production values also dominate this handsome but ultimately frustrating trade paperback collection of panels from the author’s weekly strip in the now-defunct Boston Phoenix. Stevens’ clearly evident rendering abilities hark back to those of the engravers of yesteryear, but his photorealism makes me think of nothing so much as an alt/lit Alex Ross.

After admiring the impressively labor-intensive application of crosshatched tonalities and watercolors, I wished that there was a bit more connective tissue to the semi-autobiographical bones and meat of the book than the most prominent theme of drunkenness.

_____________________________________________________________

Linen Ovens by Keren Katz/Molly Brooks/Andrea Tsurumi/Alexander Rothman (self published)

My favorite of the works I got at Brooklyn’s Grand Comics Festival, this is an anthology that takes advantage of the compatibility of poetry and comics. Poetry can be greatly enhanced by drawings which do not seek to be redundant with the accompanying words, but rather work in an oblique manner with the text, or run parallel to it.

Under Tsurumi’s striking cover, handlettering is intrinsic to these pieces; it guides the eye through the soft watercolors of Rothman, for example. Color figures most notably in the semi-abstracted panel transitions of Brooks and the unusual and effective pastel illustrations of Katz.

_____________________________________________________________

The Crow: Curare by James O’Barr and Antoine Dodé (IDW)

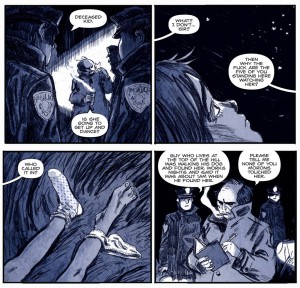

It feels to me like a thousand years have passed since the emergence of O’Barr’s pre-Vertigo character/property The Crow in comics and feature films, but here at this late date is a new miniseries drawn with rounded expressivity by Dodé, involving a cop’s desperate search for a child murderer, aided by the shade of one of the pathetic victims. In the two issues I read in PDF form, the title character has yet to rear his head, but the stage is certainly set in a most murky and moody manner by Dodé’s beautifully unforced storytelling.

The poignancy of the art is further facilitated by its being printed from uninked pencils which are then digitally colored with a limited palette of primarily sepia and pale blues. Of course, since this is an IDW publication, as with most mainstream comics, the lettering is digital, which tries but fails to detract from the rich personality displayed in the artwork.

_____________________________________________________________

March: Book One by John Lewis, Andrew Aydin and Nate Powell (Top Shelf)

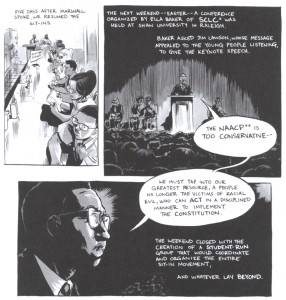

This book is partly written by its subject, the distinguished civil rights pioneer Congressman John Lewis and since it details the early years of the struggle for desegregation in southern states by African-Americans, it justifiably boasts a back cover blurb by former President Bill Clinton. It is a story that we have heard before, but one that bears repeating in a time when a rotten cluster of power has gutted the voting rights that were so hard won.

One might have expected such a meaningful project to be published by a high-profile mainstream company such as Marvel or DC, who would presumably bring it to the widest possible audience; but instead it is the product of a smaller company known for artist-owned comics, Top Shelf. This makes it odd that the book is copyrighted only to Lewis and his co-writer/press secretary Aydin, omitting the artist who does much of the heavy lifting here, Nate Powell. Because, apart from the unquestionable historical importance of the very real experiences of Lewis, it is surely Powell’s dramatic layouts that make this narrative function as well as it does in the comics form and his lush halftones are some of the best I have seen since the glory days of Ditko and Wrightson in the Warren magazines.

_____________________________________________________________

XIII: The Irish Version by Jean Van Hamme and Jean Giraud (Cinebook)

I really looked forward to the English translation of this book because I wanted to see Giraud drawing in a contemporaneous mode—-and while I am not disappointed in his drawing and storytelling in any way, it is at the service of a somewhat standard adventure story in which the entire Irish/English conflict is boiled down to be the backdrop of the origin tale in a long-running superspy narrative that makes the artist’s Blueberry westerns seem progressive in comparison. Besides that, the art is printed in a format so reduced that it becomes difficult to read, much less show Giraud’s impeccable deep-space compositions to advantage.

The coloring likewise suffers somewhat from a standardized approach, which drives the point home that Giraud is a much better colorist than anyone his work has been desecrated by since the peak years of Metal Hurlant. However, as he did on his final two Blueberry volumes, O.K. Corral and Dust, Giraud himself put his hand into the coloring to a limited degree to digitally “dirty up” the art, to add lighting effects and ruddier complexions, all of which go a long way to improving the look of what are, sadly, some of the last Moebius comics we shall ever see.

_____________________________________________________________

Interesting thoughts re: Clowes and Ken Parille-as-Kinbote, particularly since Vladimir Nabokov in general and Pale Fire in particular are repeatedly mentioned in The Art of Daniel Clowes Modern Cartoonist, co-edited by KP!

Was that intentional on your part?

I read Pale Fire in 2005 and immediately noticed the correspondence to Clowes’ Ice Haven—then I read an old Comics Journal interview with Clowes where he discusses his appreciation for Nabokov in general and Pale Fire in particular. While at Columbia U.I wrote an odd paper about the confluence of Clowes, Nabokov and Orhan Pamuk, which incorporates some aspects of Kinbote’s methodology; it is online here:

http://www.thearteriesgroup.com/MetaNarrativeAndHypercriticism.html

I sent it to Clowes and he seemed amused by it, so that was nice. I don’t have The Art of Daniel Clowes—I guess I should check it out.

Yeah, PF is astonishing. Also a very noticeable influence on Gene Wolfe.

Right on: “To my mind, a good thing is that so many of the young cartoonists now emerging reject the contrived plasticity of technique and assembly-line methodology that defines contemporary mainstream comics to instead employ an auteuristic, handmade aesthetic in their work.”

These are great reviews. Spot on. When I got the Clowes book I wrote an email to Ken Parille comparing him to Kimbote (in a good way!)

Pingback: Workin’ Hard | Versequential

Pingback: Kibbles ‘n’ Bits 8/28/2013: Watch the Throne — The Beat

Thanks, James.

“a classic that needs to be read by anyone who writes criticism on the internet.”

Very true.

Clowes: “I felt like a lot of these guys have an agenda that has nothing to do with what they’re looking at. And there’s something about them — I don’t know. They are sort of a negation of the artistic process: you become a critic in order to engage with this art form but you proceed without really engaging it, just trying to find a story that fits some preconceived narrative or settles some unspoken score. I found it really appalling in a lot of cases, and oddly fascinating.”

As I’ve said before, the anti-intellectual, anti-critical obsessions of comics seem fairly philistinish to me. Criticism has a much longer and much more solid aesthetic pedigree than comics does. If I really have to choose between James Baldwin and Dan Clowes, I know who I’m going to pick.

Also amusing that Clowes is criticizing criticism for not engaging in the object at hand while engaging in criticism without actually pointing to anyone in particular, or talking about anything specific.

I think you may be misinterpreting Clowes, there, Noah. He comments on criticism a lot in his work, to be sure and imbeds plenty of fodder for critics to hash over in his work; he even has a very amusing comics critic character Harry Naybors, who rears his head in Ice Haven. But he doesn’t necessarily excoriate all critics and in fact has benefited greatly from the near-universal critical acclaim his work had received.

I’m sure Clowes likes critics who like his work.

That Clowes story isn’t attacking intellectualism or criticism, it’s about a type of self-absorbed critic gaining prominence on the internet: who resists engagement with art, reacts aggressively when his desire for escapism is challenged, and cherrypicks details to support a crude master narrative/private vendetta.

“Criticism has a much longer and much more solid aesthetic pedigree than comics does. If I really have to choose between James Baldwin and Dan Clowes, I know who I’m going to pick.”

Criticism is as old as art, so you could say the same about the novel. Art has also engaged with criticism from the beginning. I don’t see the connection to James Baldwin, especially since the standard hoisted around here is Alan Moore and Neil Gaiman.

“Also amusing that Clowes is criticizing criticism for not engaging in the object at hand while engaging in criticism without actually pointing to anyone in particular, or talking about anything specific.”

But he wrote a work of fiction that is specific to address the larger pattern. If calling out real people is always preferable, why write fiction at all?

“That Clowes story isn’t attacking intellectualism or criticism, it’s about a type of self-absorbed critic gaining prominence on the internet: who resists engagement with art, reacts aggressively when his desire for escapism is challenged, and cherrypicks details to support a crude master narrative/private vendetta.”

Yeah, I understand what he’s claiming. I’m deeply unconvinced. It’s the same old shibboleth’s always trotted out by artists when they feel critics have been unfair to them, waah.

And sure, there’s lot of bad criticism, like there’s lots of bad art and lots of shoddy thinking. Clowes’ quote would, IMO, be an example of all of those.

And I mentioned James Baldwin because he’s a great critic. Not sure why you think Gaiman and Moore are some sort of standard here? They’ve both come in for lots of harsh criticism here.

Just to be clear; I dislike most of Clowes’ work that I’ve read, and pretty much hated Ice Haven and everything in it, including the treatment of the critic. But…Clowes is a smart guy, and I think actually often see himself as a critic, with a fairly agonized relationship to comics and art. So…really I should see the quote in context, I guess. There could well be more there than the simple-minded attack on critics that it seems to be. Deelish could well be doing Clowes a disservice.

Noah says “It’s the same old shibboleth’s always trotted out by artists when they feel critics have been unfair to them, waah.”

Shibboleth?.. How many limbs, mouths and eyes does it have and how can I summon it? What critics shall we kill when it comes? I’m up for setting Shibboleth on a few 70s/80s british music journalists.

Well Noah, YMMV and all but I just revisited Ice Haven this morning and I still think it’s brilliant, possibly one of my favorites by Clowes, but I generally like his stuff a lot. One random observation: no one outside of Iain Banks does better oddball names than Clowes.

Yeah. The only Clowes I’ve really been able to stand is Death Ray.

Interesting. I liked The Death-Ray well enough, but I’d probably rate it lower than most of his stuff and I find myself wondering how well it would be received by someone not familiar with superhero tropes.

I talk about why I find it more congenial than most of his work here, if you’re interested:

https://www.hoodedutilitarian.com/2013/08/superheroes-with-cigarettes/

Yeah, I read that when you first posted it. You raised some good points, though to say that The Death-Ray “just comes across as another superhero comic” strikes me as a really odd reading of the material, regardless of the Lee/Ditko references etc.

MAD Magazine is often brought up in discussions about Clowes and this rings true for me; at one appearance I even told him I thought that I saw a lot of Dave Berg in his stuff, which seemed to amuse him. Like Berg, Clowes seems to have a talent for depicting people in the worst possible light, even people who aren’t really all that awful and he manages this both visually (even his pretty girls look sort of like mutants) as well as through their actions and words.

Huh. Haven’t thought about Dave Berg in a long time. Is he still around at all?

No, he died in 2002. And I have to say that this bit from his Wiki page depresses the heck out of me:

Rick Altergott is another one who seems to have a huge MAD influence, and not just Wally Wood (often mentioned) but less-celebrated members of “the usual gang of idiots” such as George Woodbridge and Jack Rickard as well. Of course Rick Altergott doesn’t do the kind of New Yorker-friendly stuff that Clowes does, though I think he’s every bit as brilliant.

Come on, the New Yorker loves stories about panty-sniffing hoboes

Well, maybe if Michael Chabon or Jonathan Lethem wrote such a story…

Wow, Daniel, you nailed it with that Dave Berg comparison. Almost everything, for example, about this strip reminds me of Clowes — especially that first panel, in word and image.

I like Berg’s drawing more, I think? I really like that weird lamp post in the first panel for example. Kind of reminds me of John Porcellino….

Thanks Peter. Yeah, that strip really does have a Clowes feel, especially the track suit and specs combo and the spare, almost diagram-like street scene.

Berg definitely had drawing chops. Much though I love this later Berg stuff, his “Lighter Side…” strips from the early sixties were often quite beautiful. He had particular technique of drawing figures in motion with a lighter wash than surrounding panels that I thought was really quite elegant. And as Lynda Barry noted, he drew great teeth.

I see a bit of George Price in Clowes too, visually and thematically, but more Dave Berg!

I’m glad to see some discussion of — and respect for — Dave Berg. He’s really the forgotten man of Mad magazine; he was treated with contempt by many of the Mad bullpen, including Bill Gaines.(Read Frank Jacobs’ biography of Gaines.)But I think he was brilliant when at the top of his form.

Someone should do an article on him for HU. I wonder who…

…uh, someone…

Oh shit.

Do it!

For all I know, Clowes may not even think of himself as having been influenced by Berg. Maybe it was more of an osmosis thing, having absorbed the influence of MAD overall, Berg included.

Dave Berg is like the Ernie Bushmiller of MAD, the more square and out of touch his stuff became, the better it got. He really came into his own in the seventies with his bearded, bell bottomed, twenty-somethings and their polyester leisure suited parents.

He was also a master gagman and a pretty shrewd satirist.

What say, Noah…shall I do a Berg article?

Noah: “And sure, there’s lot of bad criticism, like there’s lots of bad art and lots of shoddy thinking. Clowes’ quote would, IMO, be an example of all of those.”

Failure to engage with a work of art is the essence of bad criticism. If there’s some problem with Clowes’ thoughts, painting him with a broad anti-intellectual, anti-critical brush, namedropping James Baldwin, accusing him of hypocrisy for not naming names, and calling him a crybaby doesn’t communicate it.

“And I mentioned James Baldwin because he’s a great critic. Not sure why you think Gaiman and Moore are some sort of standard here? They’ve both come in for lots of harsh criticism here.”

You haven’t justified using Baldwin because Clowes is obviously not inveighing against all criticism. Does Baldwin do something Clowes describes and make it work? If not, why is he here?

You have a way of using the Western Canon as a blunt instrument on anything you dislike:

“Do you really see Clowes’ moral vision as especially serious or insightful compared to folks who actually care about that stuff — George Eliot, Tolstoy, Jane Austen, even Dickens? It all just seems pretty thin gruel by those standards to me…”

I just find the pop culture stuff more convincing as your critical North Star because you only trot out the likes of Baldwin and Eliot for that kind of tactic. You frequently refer to Moore and Watchmen as among your favorites, and you judged the Gaiman-edited volume of Best American Comics on the head-scratching basis of how well its selections resembled Sandman. Where is the moral vision of Tolstoy with them, or that Anne Hathaway Disney movie about the princess under a spell that makes her do whatever anybody tells her to?

I’m no Clowes fan but I think Deelish is right. I think that criticism Clowes made of certain critics is a fair observation and I dont think it matters that it doesnt apply to all critics or any specific critic.

I’ve seen this complaint about not naming specific critics and academics on this blog several times, but why does everyone feel so comfortable criticizing general groups like fanboys and mainstream comic creators?

I always thought Ella Enchanted was an extremely morbid concept that would have troubled me as a child.

??? I don’t know what you’re talking about. Some of Moore’s work is among my favorites; some I think is really problematic. I don’t think I’ve ever cited Gaiman as being a favorite; I wasn’t judging his book on whether it was like Sandman, but was pointing out that Sandman (which I have mixed feelings about) seems not to be a major influence on comics these days.

I mention Baldwin all the time. He’s one of my favorite writers. I mention him way more often than Gaiman, who I hardly ever think about, honestly.

And I think Ella Enchanted is interesting in terms of what it says about female empowerment…but I don’t think I claimed its moral vision was unquestionable (in fact, I talked about weaknesses in terms of the book it was based on.) I do like the book better than anything I’ve read by Clowes. Gail Carson Levine is a smart creator and a good writer. Her take on female adolescence and female relationships is certainly less cliched than Clowes’ in Ghost World.

Anyway, I don’t like Clowes much, but I think he’s a smart guy, I kind of liked Death Ray, and I think that comic about critics looks okay. I’m not exactly sure why my ambivalence/disinterest in him strikes you as some sort of personal insult. Most people like him more than I do; why work yourself into a lather just because some guy out there on the internet isn’t especially enthusiastic?

Alex, I’d print a Berg article, sure.

Oh, and I’m willing to walk back my take on that Clowes quote. I’m still not actually sure where it comes from; is it lifted from an interview? From a comic? I don’t really know what to make of it till I have a better grasp of the context, I guess.

Robert, generally criticism of mainstream comics creators focuses on individual titles or people when it’s brought up here? And I’m willing to say that fannishness has some advantages (I don’t think I’d have a book contract if it weren’t for comics’ history of fan scholarship, and the subsequent willingness of academic comics types to take seriously someone who isn’t credentialed.)

It just seems fairly easy and not especially useful to say, “critics I dislike do x” without some more definite sense of where those critics are, or of who you’re talking about. “Mainstream comics creators” is a pretty circumscribed group compared to “critics” in general, it seems like.

And isn’t it a bit too easy, too, to just say, “well, any critic you can bring up in contrast isn’t who he’s talking about, so it doesn’t count”. At least with mainstream comics creators, you can say, well, here’s a mainstream comics creator who doesn’t fit that niche, and then you can argue the merits back and forth. But who can disagree with “I dislike bad critics”? Everybody dislikes badness. You might as well say, “I hate rotten food.” Okay, sure…but so what?

But as Suat says, Clowes take on critics and criticism in some cases seems significantly more nuanced — taking into account the fact that criticism is a part of the creative process, for example, and that critics and creators aren’t necessarily all that separate a group. It seems kind of cruel to hold him to his most simplistic formulations (though there could well be irony in there in context; he might be making fun of that condemnation of bad critics for all I know.)

And Ella Enchanted is supposed to be disturbing! Ella’s plight is absolutely meant to be terrible and terrifying. They dumbed it down and put a smile on it for the movie, as they will, but parts of the book are, and are meant to be, a grim depiction of gendered violence and servitude.

And re: James Baldwin. Baldwin talks a lot about race and art, and his amazing essay “The Devil Finds Work” is totally harnessing a series of films to his own interests and concepts; his personal background and his analysis is way more important than the artwork he’s talking about. That kind of approach (talking about racism, making the artwork secondary to the concept) is the sort of thing that often causes accusations such as those Clowes is making (i.e., the critic isn’t engaging with the work, the critic is self-absorbed, what have you.) So…I don’t think it’s really sufficient to just say, “of course Baldwin isn’t who he’s talking about.” Baldwin really could be who he’s talking about…and indeed, almost any critic could be who he’s talking about, since the accusations leveled are general enough to mean just about anybody you don’t happen to like for whatever reason. (Again, always assuming we’re supposed to be taking Clowes’ statements at face value, which we’re really probably not.)

“Not sure why you think Gaiman and Moore are some sort of standard here? They’ve both come in for lots of harsh criticism here.”

Can you point me to some harsh criticism you’ve written of either?

“I wasn’t judging his book on whether it was like Sandman, but was pointing out that Sandman (which I have mixed feelings about) seems not to be a major influence on comics these days.”

It certainly seemed in that essay as if you were casting “like Sandman” as a positive thing, and your only criticism of it was that the art was uneven. I thought it was strange to criticize a best comics of the year anthology as including nothing like Sandman, or even to comment on that, really. I don’t turn my nose up at fantasy, but I remember Sandman being twee and void of drama.

“And I think Ella Enchanted is interesting in terms of what it says about female empowerment…but I don’t think I claimed its moral vision was unquestionable (in fact, I talked about weaknesses in terms of the book it was based on.) I do like the book better than anything I’ve read by Clowes. Gail Carson Levine is a smart creator and a good writer. Her take on female adolescence and female relationships is certainly less cliched than Clowes’ in Ghost World.”

I just why the heavy artillery of Tolstoy and Eliot is not rolled out for something like that, whether to attack its weakness or put its success in perspective. You say it’s better than Ghost World in a serious-sounding way, so surely it’s more deserving.

“I’m not exactly sure why my ambivalence/disinterest in [Clowes] strikes you as some sort of personal insult. Most people like him more than I do; why work yourself into a lather just because some guy out there on the internet isn’t especially enthusiastic?”

Ambivalence/disinterest… not especially enthusiastic… you are aware I can read your site, right?

“I’m still not actually sure where [the Clowes quote] comes from; is it lifted from an interview? From a comic? I don’t really know what to make of it till I have a better grasp of the context, I guess.”

It comes from an interview quoted in The Daniel Clowes Reader. Clowes is explaining how his encounters with “internet guys,” or self-appointed critics with their own websites, on the press junkets for his movies inspired that comic. You can agree or disagree, but let him say what he’s saying if you’re going to argue, you know? (“Well, I think he’s talking about himself.”)

“[Baldwin’s] amazing essay “The Devil Finds Work” is totally harnessing a series of films to his own interests and concepts; his personal background and his analysis is way more important than the artwork he’s talking about. That kind of approach (talking about racism, making the artwork secondary to the concept) is the sort of thing that often causes accusations such as those Clowes is making…”

The existence of criticism that doesn’t fit the mold of telling people how they should spend their weekend doesn’t disallow any articulation of standards for criticism. Addressing a film’s racial politics doesn’t mean not dealing with it, quite the opposite. That job is still beholden to standards like honestly engaging and making a solid case about the work. Baldwin makes claims one can argue with; not just “film X frightened me at 12, film Y eroticized me at 13”. He goes further than an unchallengeable account of his personal reactions and he doesn’t substitute a narrative about the artist for a discussion of the art. If a critic’s only encounter with art consists of “trying to find a story that fits some preconceived narrative,” there’s no discovery and it’s not an adventurous essay. If he misrepresents the art to fit it to his expectations or denounces it because he can’t, that’s a failed encounter with art. If he has a doctrinaire concept of what “good art” does that he doesn’t allow real art to challenge, if he has standards he refuses to acknowledge or analyze, he will likely fail.

Hey! A Dave Berg article over at tcj.com:

http://www.tcj.com/my-friend-dave/

It even includes a quotation from a certain Peter Sattler regarding Clowes: