“Professor,” the commander replied swiftly, “I’m not what you term a civilized man! I’ve severed all ties with society, for reasons that I alone have the right to appreciate. Therefore I obey none of its regulations, and I insist that you never invoke them in front of me!” — Jules Verne, Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea

When it’s steam engine time, people steam engine. — Charles Fort

The Engineer as Superman

The nascent genre of science fiction found a hospitable place in the nineteenth century serial novel. Every day seemed to bring a new crop of technological wonders: the telegraph and telephone, photography, steam trains and steamships, electric generation and illumination, anaesthesia, vaccination, the internal combustion engine… The reading public was entranced by these tokens of progress, and was eager to see the new age fictionalised.

One author above all embodied this new scientific sense of wonder: the French novelist Jules Verne (1828–1905). His series Les Voyages Extraordinairescertainly lived up to its title, taking the reader Around the world in Eighty Days,Off on a Comet, From the Earth to the Moon, on a Journey to the Centre of the Earth, and Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. Verne remains as of 2012 the second most-translated fiction author in the world, after Agatha Christie.Verne is of interest to us, in this prehistory of the superhero, for two reasons.

First as the populariser of technological marvels, much imitated; a direct descent can be argued from Verne’s adventure tales, through dime-novel Edisonades and science-fiction pulps, to the first superhero comics. And, indeed, we’ll trace that descent in more detail in subsequent installments.

Second, as one more writer who helped shape the popular figure of the superman. Captain Nemo is the villain/hero of Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea (1870). He is the master of the Nautilus, a mighty submarine that defies the earthbound nations of the world and their navies, sinking warships at will:

“On the surface, they can still exercise their iniquitous laws, fight, devour each other, and indulge in all their earthly horrors. But thirty feet below the (sea’s) surface, their power ceases, their influence fades, and their dominion vanishes. Ah, monsieur, to live in the bosom of the sea! …. There I recognize no master! There I am free!”

This anarchist has, in effect, declared war on the entire world, reserving particular hatred for the British Empire. The reason for this is not given in Leagues, but in a subsequent sequel of sorts, The Mysterious Island (1874) we learn that Nemo is the Indian prince Dakkar of Bundelkund, whose family was wiped out by the British during the Great Mutiny. But the earlier book disdains such explicit explanation: Nemo strikes us as a superman sui generis, master of men and challenger of the elements.

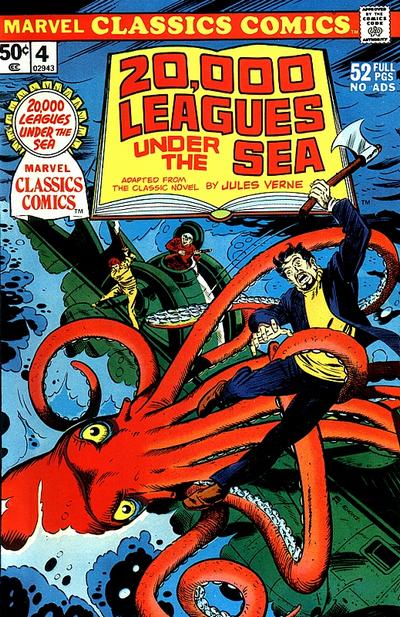

Nemo and crew fighting a giant squid

(Is there an indirect link between Captain Nemo and the aquatic superhero/villain Namor, the Sub-Mariner, who first appears in a 1939 comic book? Both are princes who rule the seas from under the waves, both wage war against the hated ‘surface men’ and sink their ships at will. Creator -cartoonist Bill Everett (1917–1973) claimed his inspiration was Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, and that he arrived at the name ‘Namor’ by spelling ‘Roman’ backwards. But surely there’s an echo of ‘Nemo’ in ‘Namor’, even if an unconscious one?)

A 1976 version of the squid fight; art by Gil Kane and Ralph Reese

Yet another of Verne’s scientific supermen was Robur, who ruled the air as Nemo ruled the sea, from his propellor-powered airship Albatross in the 1886 Robur the Conqueror.

Robur’s Albatross (left) defeating the balloon Go Ahead in a race; art by Leo Benett

Robur had turned decidedly villainous, with dreams of world domination, by the time of the sequel The Master of the World (1904); his successor to the Albatross is the even deadlier Terror, which can navigate the air, the land, or below the sea:

The Terror (L’epouvante)

This is the trope of the Ultimate Weapon, again familiar to superhero comics, generally in the hand of the villain. It is possible Verne was influenced by a derivative work to transform Robur from aeronautic pioneer to would-be world conqueror. This was Edward Douglas Fawcett‘s Hartmann the Anarchist, or the Doom of the Great City (1893), in which a Robur-like evildoer rains death and destruction down on a helpless London from his airship:

illustration for Hartmann the Anarchist.

With eyes riveted now to the massacre, I saw frantic women trodden down by men; huge clearings made by the shells and instantly filled up; house-fronts crushing horses and vehicles as they fell; fires bursting out on all sides, to devour what they listed, and terrified police struggling wildly and helplessly in the heart of the press.

A chilling premonition of the WWII blitz! It is well to remember that the end of the 19th century viewed anarchists with particular dread, and with good reason, much as we today fear terrorists.

Verne’s influence was enormous, inspiring a sub-genre of popular literature that the science-fiction critic John Clute has dubbed ‘Edisonade’, after Thomas Alva Edison (1847-1931), the famed inventor of the phonograph, light bulb, motion picture, microphone, and hundreds of other marvellous devices. (Edison himself occasionally turned up in science fiction; he builds a gynoid robot in L’Eve Future, he battles extra-terrestrials in Edison’s Conquest of Mars.) Edison is the real-life avatar of the mad scientist’s benevolent equivalent in fiction, whose epigones continue in modern superhero tales: Reed Richards of The Fantastic Four, for instance.

The Steam Man of the Prairies

Typical of the genre is Edward Ellis‘ The Huge Hunter, or the Steam Man of the Prairies (1868), in which the eponymous automaton (pictured above) drags around a crew of intrepid young adventurers to fight Indians and bandits in the old West. The series was hugely popular, and duly plagiarised. We can observe that the Steam Man’s descendants today number such superheroes as Robotman, Steel, Machine Man, Iron Man, or War Machine.

Let’s take note of other European contributions to 19th century popular culture that have echoed down to the present, contributing to the crowded attic of superhero tropes.

Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1803-1930), in his 1871 novel Vril, the Power of the Coming Race, presents an ancient civilisation living in vast underground caverns. This “coming race”, the Vril-Ya, has mastered a sort of universal force known as Vril that gives them an array of powers, allowing them to fly, heal any wound or disease, animate mechanisms, or destroy an entire city with a thought. In short, the first literary evocation of super-powers with a pseudo-scientific rationale. In modern superhero comics, Silver Surfer and Green Lantern are today’s most successful wielders of Vril-like energy.

The Vril-Ya live in an underground utopia. (Underground races and civilisations are staples of superhero comics: see the Mole Man’s and the Deviants’ realms.) However, the human narrator fears that some day they will burst up onto the Earth’s surface and subjugate humanity:

Only, the more I think of a people calmly developing, in regions excluded from our sight and deemed uninhabitable by our sages, powers surpassing our most disciplined modes of force, and virtues to which our life, social and political, becomes antagonistic in proportion as our civilisation advances,–the more devoutly I pray that ages may yet elapse before there emerge into sunlight our inevitable destroyers.

The Vril-Ya, a race of superior post-humans, are also kin to science fiction’s Slans and comic books’ X-men: super mutants, to be feared. This novel, though largely unread today, made a sensational impact at the time; and its influence was often sinister. Many thought the book was non-fiction. Occult Vril societies sprang up and continue to this day; the book had a decided influence on Nazi ideology. A race of supermen destined to rule the earth!

In 2007, writer Josh Dysart and artist Sal Velluto created the comic Captain Gravity and the Power of the Vril, whose eponymous superhero tapped Vril for his fantastic powers to fight the Nazis, themselves bent on acquiring the mystic energy.

art by Sal Velluto and Bob Almond

I prefer to dwell on a more wholesome influence: in 1886, John Lawson Johnston named his nourishing beef tea paste Bovril, combining the Latin bos (ox) with Bulwer-Lytton’s Vril. And the writer of these lines can indeed attest to this fine drink’s revivifying powers, particularly on winter days.

Early advertisement for Bovril

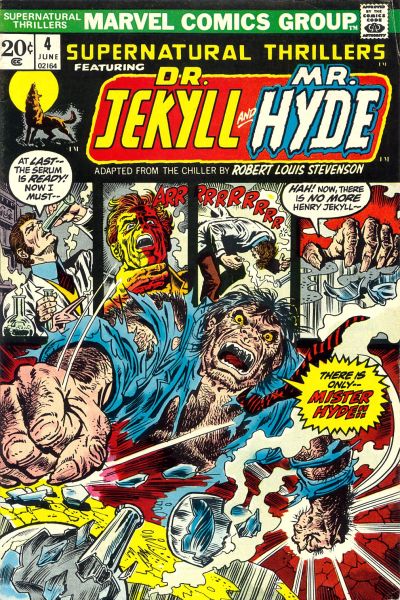

In 1886, the novella Strange Case of Dr Jeckyll and Mr Hyde, by Robert Louis Stevenson (1850-1894) was published to universal acclaim. This tale of a kindly doctor who changes into an evil, twisted double on imbibing a potion has strongly influenced the modern superhero, with his or her double identities.

Art by Ron Wilson, John Romita, and Ernie Chua

More directly influenced superheroes include the Hulk, the Demon, Ghost Rider, Man-Wolf, the Badger, and Rose and the Thorn; while supervillains of the type are numerous, such as Eclipso or the Lizard. Stevenson’s penetrating allegory of humans’ multiple nature thus lives on in the garish jungle of pop culture.

In 1905, Emmuska Orczy (1865 –1947 ) published The Scarlet Pimpernel;the novel tells the adventures of Sir Percy Blakeney– a ridiculous fop of a British aristocrat, who leads a double life as the Scarlet Pimpernel, a dashing hero dedicated to rescuing aristocrats from the guillotine in the terror years of revolutionary France.

The Pimpernel was a sensation in print and on stage, and proved equally successful in the movies; so too did Orczy’s numerous sequels.

We seek him here, we seek him there,

Those Frenchies seek him everywhere.

Is he in heaven?—Is he in hell?

That demmed, elusive Pimpernel.

The Scarlet Pimpernel has a good claim on being the first full-fledged superhero; we shall return to his influence on such characters as Zorro and Batman.

Next: Enter the Detective, and the anti-supermen of H.G.Wells

Great article and lots of fun to read also, which is something of a relief in these bloviating times … Jules Verne’s many incarnations of the superman engineer may have been driven by his deepest, more enduring obsession: the robinsonade.

The idea of plunging a character into a technological vacuum which he must survive by creating technology out of nothing was Verne’s ultimate fixation.

The Mysterious Island was his best robinsonade but he played with the concept in most of his novels … over and over, we read of a super-engineer/savant creating shelter against a hostile environment solely with his Linnaean-equipped, Edisonian mind.

The delicious thrill of being in intimate contact with a hostile void whilst simultaneously being its potential master is the root emotion here …

Behind every superman lurks an infant being potty-trained?

“Behind every superman lurks an infant being potty-trained?”

Truth.

There’s much to be said for the properly toilet-trained superhero … it will probably said here, in the HU

Alex here. Thanks, Mahendra, for the kind words…are you the Mahendra Singh who drew that wonderful version of ‘The Hunting of the Snark’? If so …are you aware of Mervyn Peakes’ version for Faber&Faber?

“bloviating”…makes me nervous, that. I hope you’re not referring to the other HU writers, whom I find witty and wise in the main. And I’m afraid there’s some bloviating coming up from me as the series goes on.

Speaking of the series, there are 5 more episodes to go:

Part 4: crime fiction, Conan Doyle, H.G.Wells.

Part 5: America, the coming of the Western

Part 6: the Pulps

Part 7: the comics, and the birth of Superman

Part 8: a summing-up (and me whining).

Should be coming out every 2 or 3 weeks, but that’s up to the good Captain Noah.

A couple of regrets:

In part 1, I should obviously have written about De Sade as really the first apologist of the superman.

In part 2, while listing the “superheroic” attributes of Monte Cristo, I should have added the ‘secret lair’: his hidden island cave is the equivalent of the Batcave or of Superman’s Fortress of Solitude.

Yes, I’m the Snark GN artist and yes, I’ve seen Peake’s wonderful Snark illos … I do think that often, in describing the visual arts, words should be used sparingly.

And Conan Doyle, he pretty much perfected the super-hero/sidekick ensemble with Holmes & Watson.

Conan Doyle, Verne and Lewis Carroll, the three amigos of Victorian superhero literature. As far as LC goes, isn’t Alice the prototype of everygirl as supergirl?

Looking forward to the rest of your series.

Cheers!

Regarding Alice…I think it was GK Chesterton who pointed out that Alice was a very commonplace girl in extraordinary circumstances, and that this was necessary for the fantasy to work.

So, yes, “everygirl” as you put it. As for “supergirl”…well, at the end of ‘Alice in Wonderland” she overthrows the nightmarish court of the Queen of Hearts: “You’re just a pack of cards!” And at the end of “Through the Looking-Glass”, she shakes the Red Queen into a kitten (something that nearly happened to me…phew.)

So, okay, MS, Alice is the prototypical Supergirl. I only wish that fool Tim Burton hadn’t taken the notion so literally and crudely.

The Tim Burton film … speak not of that … thing. The Jonathan Miller BBC version is my favourite.

GCK also thought that the Snark wasn’t for children. His superhero was Jesus and those kind of superheros are not much fun in the suspenseful thrills department. Talk about deus ex machina, that’s pretty much the whole Bible, eh?

I remember reading Neil Gaiman on his blog disagreeing with the idea that Alice is normal. He wrote:

“The first thing I knew when I started American Gods – even before I started it – was that I was finished with C.S. Lewis’s dictum that to write about how odd things affect odd people was an oddity too much, and that Gulliver’s Travels worked because Gulliver was normal, just as Alice in Wonderland would not have worked if Alice had been an extraordinary girl (which, now I come to think of it, is an odd thing to say, because if there’s one strange character in literature, it’s Alice).”

http://www.neilgaiman.com/p/Cool_Stuff/Essays/Essays_By_Neil/All_Books_Have_Genders

He doesn’t develop the idea, but I assume it’s because she’s too accepting of the odd stuff around her? Plus it’s just a dream in her head, anyway? Which I guess could be read as a normal day in the life of a child, or more abstractly, as if she has no connection to any sort of reality, since virtually all we see of her is just a dream in her head…

Alice is not a strange character … proof? The things she keeps inside her head seem strange to her only because she is not.

The secret to the mostly non-descript Alice’s peculiar ability to intrigue generations of readers is the fact that the entire fictional Carrollian Multiverse she inhabits loves her.

She never knows it and probably doesn’t care, but she is the cynosure of her reality.

Try beating THAT, all you other phoney baloney superheros.