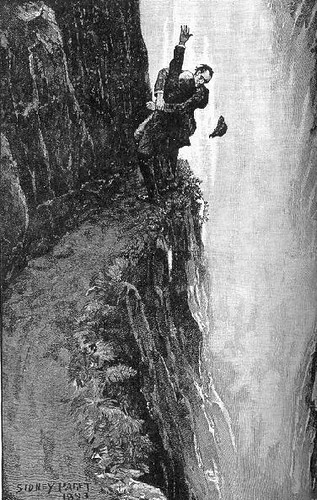

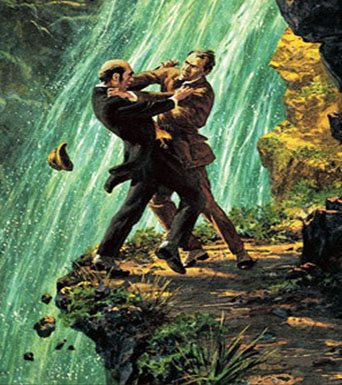

Holmes and Moriarty at the Reichenbach Falls

“My mind,” he said, “rebels at stagnation. Give me problems, give me work, give me the most abstruse cryptogram or the most intricate analysis, and I am in my own proper atmosphere. I can dispense then with artificial stimulants. But I abhor the dull routine of existence. I crave for mental exaltation. That is why I have chosen my own particular profession, or rather created it, for I am the only one in the world”– Arthur Conan Doyle, The Sign of the Four

Enter the Detective

Science-fiction was not the only popular genre to soar into prominence in the 19th century. Crime fiction also evolved into a major purveyor of thrills; and, like science-fiction, would be an important source of tropes for the superhero.

Tales of crime had, of course, been told for many centuries before; however, behind a mask of conventional pieties, the reader’s sympathies tended to be guided towards the criminal. This is understandable in that the social structure was widely perceived as oppressive and unjust; the repression of crime was a corrupt and ineffective process accompanied by excessive harshness and cruelty– in 1800 England, one could be hanged for the theft of a handkerchief.

But the establishment of effective police forces, along with the evolution of penal and social reforms, gradually shifted sympathy to the crimefighter. In France, the 1828 memoirs of Vidocq (1775-1857) ,the first true-life detective to set pen to paper, were the inspiration for the whole fictional sub-genre of the police procedural, as later first expressed in the novels of Emile Gaboriau(1832–1873) starring Inspector LeCoq.

Vidocq– criminal turned policeman

The policeman as hero, however, was not a universal taste. A new figure arose, like nothing existing in real life: the amateur detective.

The first of these was born from the pen of Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849), in his 1841 short story The Murders in the Rue Morgue. Therein was introduced the Chevalier Charles Auguste Dupin, a reclusive aristocrat who seems to solve crimes purely for the pleasure of puzzle-solving. This was the template for the amateur sleuth, one who upheld the law without being of the law; thus, the reader was able to eat his anti-authoritarian cake and have it.

The superhero replicates this delicious ambiguity: an outsider fighting injustice with little help, or even outright hostility, from the official forces of law and order, who would like nothing better than to unmask and lock up Zorro orSpider-Man.

Of course, the most renowned detective of all was the immortal creation of Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 –1930): Sherlock Holmes. Here we meet the superman as ultimate rationalist, before whose mind no mystery could stand; also a master of disguise, a formidable pugilist, a drug addict and crack violinist…the tradition of the eccentric hero has one of its most beguiling incarnations in him.

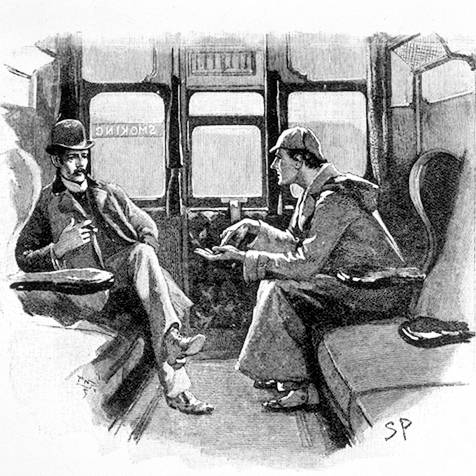

Dr Watson and Sherlock Holmes; illustration by Sydney Paget

For our purposes, we can note some aspects of the Holmes stories that are (in however distorted a manner) now commonplace in the superhero tale.

The mantle of ‘World’s Greatest Detective’ is often assumed by the masked crimefighter, notably Batman.

With Holmes’ companion (and narrator of his adventures) Doctor Watson, we have a codification of the sidekick– a useful stand-in for the reader, and recipient of much expository dialogue.

Illustrator Sydney Paget introduced the deerstalker cap, curved meerschaum pipe, and Inverness cape that became iconic attributes of the hero, after they were taken up in theatre and cinema adaptations: a hero would have a costume.

In the short story The Final Problem, Doyle killed off his hero; in The Empty House, he resurrected him. Longtime readers of superhero comics will recognise a depressing tradition.

And, lastly, in The Final Problem Doyle introduces another superman, Holmes’ evil equal, the ‘Player on the Other Side’: Professor Moriarty. Here is how Holmes describes him:

He is the Napoleon of crime, Watson. He is the organiser of half that is evil and of nearly all that is undetected in this great city. He is a genius, a philosopher, an abstract thinker. He has a brain of the first order. He sits motionless, like a spider in the centre of its web, but that web has a thousand radiations, and he knows well every quiver of each of them. He does little himself. He only plans. But his agents are numerous and splendidly organised. –from The Adventure of the Final Problem

(Note the invocation of Napoleon, whom we’ve pegged as the prototype of the modern superman in

Moriarty is the arch-enemy. Prior to this, there was room for only one superman per story; the adversaries of such as Monte Cristo, Nemo or Roburwere rather blandly good or evil representatives of banal humanity. But here is the prototype for the superhero’s dedicated supervillain, as the Joker is to Batman or Lex Luthor to Superman or Dr Doom to the Fantastic Four.

Holmes and Moriarty! Pity they killed each other at the Reichenbach Falls, as illustrated below by Sydney Paget:

Crime fiction soon diversified into various sub-genres, often along class lines: the middle classes preferring “cosy” tales of detection, the working classes opting for increasingly sensationalist thrillers. It is from this second type that crime and superhero comics flowed; and the simplistic good guys vs bad guys set-up of the superhero comic also derives from this model.

The century wasn’t all given over to science and reason. Spiritualism spread far and wide, with mediums supposedly communicating with the dead or other preternatural spirits. The Society for Psychical Research was founded in London in 1882, to “scientifically” investigate ESP, hauntings, and other paranormal phenomena.

In fiction, this gave birth to the figure of the occult detective, investigator of the uncanny. The first is thought to be Sheridan Le Fanu‘s Dr. Martin Hesselius (1872), and the line has continued down to the present day via such classic characters as W.H.Hodgson‘s Carnacki the Ghost Finder, or Algernon Blackwood‘s John Silence. The occult detective is well represented among superheroes, by such as Dr Occult, the Phantom Stranger, John Constantine,Hellboy, Dr Spectrum and Dr Strange.

One occult detective, Abraham Van Helsing, was the foe of the eponymous villain in Dracula, the classic 1897 horror novel by Bram Stoker (1847–1873). The title vampire has assumed the status of modern myth; a perverse and compelling version of the superman, he has a distant affiliation to such superheroes as Batman and the Spectre. (And, of course, Dracula is one of the great supervillain archetypes; indeed, he has himself fought Superman, Batman and Spider-Man.)

Der Uebermensch

“I teach you the superman. Man is something that shall be overcome. What have you done to overcome him? … All beings so far have created something beyond themselves; and do you want to be the ebb of this great flood, and even go back to the beasts rather than overcome man? What is ape to man? A laughing stock or painful embarrassment. And man shall be that to superman: a laughingstock or painful embarrassment. You have made your way from worm to man, and much in you is still worm. Once you were apes, and even now, too, man is more ape than any ape…. The superman is the meaning of the earth. Let your will say: the superman shall be the meaning of the earth…. Man is a rope, tied between beast and superman—a rope over an abyss … what is great in man is that he is a bridge and not an end.”

Thus spake the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) in Thus Spake Zarathustra. The concept of the superman was finally articulated, and promptly misinterpreted. It is not our concern to present the superman as Nietzche intended; rather, we note that history has sadly recorded how a twisted reading of Nietzsche, coupled with equally wrongheaded interpretations of Darwin’s theory of evolution, has led to such horrors as eugenics and Naziism.

This rather disquietingly chimes with the superman incarnations we’ve examined so far– fantasies of power answerable only to itself.

It seems odd that there be a direct link between Nietzche’s superman and the comic-book Superman, but such was the case, as we’ll see in a subsequent chapter.

Beyond the superman

>

A Martian tripod, from The War of the Worlds

We leave Europe with a look at one of the founding masters of science fiction.

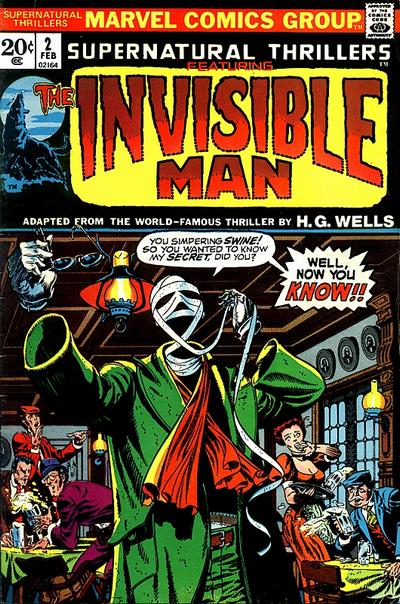

Herbert George Wells (1866–1946) was one of the most influential thinkers and writers of the 20th century; a socialist, futurist, reformer, historian and social novelist. He is chiefly remembered today for his scientific romances, novels written over an astonishing ten-year burst of creativity: The Time Machine (1895), The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896), The Invisible Man (1897),The War of the Worlds (1897), When the Sleeper Wakes (1896), The First Men on the Moon (1901), The Food of the Gods (1904).

from the Classics Illustrated adaptation of ‘The Time Machine’; art by Lou Cameron

Wells’ tales contributed important themes and tropes to the bric-a-brac of science fiction and superhero comics: time travel (The Time Machine), invisibility (The Invisible Man), the superhumanly strong visitor from another world (The First Men on the Moon), lab-born mutant monsters (The Island of Doctor Moreau), extraterrestrial invasion (The War of the Worlds), and the all-too-prophetic atom bomb (The World Set Free).

Yet the early Wells is no apologist for the superhuman. Far from it! He was, to the contrary, a strong debunker of supermen.

Consider Griffin, The Invisible Man. A psychopathic genius with an astounding power– yet he is unable to prevail against ordinary shop-clerks and innkeepers, and ends up killed by ditchdiggers. Or Dr Moreau, a monster of cold scientific cruelty, who forces adoration of him as a god upon his beast-man creations, yet is killed by them.

^nbsp;

Art by Jim Steranko

The invading Martians in The War of the Worlds are as effortlessly superior to humans as we are to ants:

Yet across the gulf of space, minds that are to our minds as ours are to those of the beasts that perish, intellects vast and cool and unsympathetic, regarded this earth with envious eyes, and slowly and surely drew their plans against us. And early in the twentieth century came the great disillusionment.

These tentacled, abhuman monsters are the ultimate product of ‘progressive’ evolution– the true destiny of the superman. They are only halted by natural exposure to Earth germs.

And the Time Traveller finds no ‘men like gods’ (to use a titular Wellsian expression) in the distant future, but rather a human race devolved into the effete and brainless Eloi and the cannibalistic, nocturnal Morlocks:

I grieved to think how brief the dream of the human intellect had been. It had committed suicide. It had set itself steadfastly towards comfort and ease, a balanced society with security and permanency as its watchword, it had attained its hopes—to come to this at last.

The War in the Air (1908) finds the unstoppable German conquest by Zeppelin of America almost accidentally halted in its tracks by a silly fool of a Cockney bicycle repairman, who copied some secret plans of an airplane out of sheer boredom.

In his postwar utopias, Wells would abandon this tone of disillusionment for ponderous exaltation of technocratic futures; but these early scientific romances effectively deflate the very idea of the superman. Then why do I bring him up in this study of superhero prehistory?

Scholars of science fiction are given to dividing SF writers into gosh-wow, technophilic ‘Vernians’ and more thoughtful ‘Wellsians’. If we follow this dichotomy, the 20th century superhero definitely derives from Vernian fiction.

But I believe Wells’ skepticism indicates an important reason superheroes never really caught on in European popular culture, except as imports from the States, burlesques, or parodies, like the French Superdupont:

Superdupont meets Supe…ah, Zipperman; script by Jacques Lob, art by Neal Adams

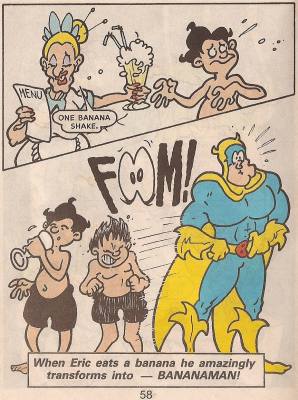

…or the British Bananaman:

Art by Terry Anderson

…or the Italian Super West:

art by Mattioli

Europeans are skeptical about extraordinary individuals — the ‘tall poppy syndrome’– and supermen certainly fit the description. A superman is most likely to be a villain, like France’s arch-criminal Fantomas, created in 1911 by Pierre Souvestre and Marcel Allain.

And when Europeans did take the superman idea seriously — as did the Nazis — the results were hideous.

No, the modern superhero could only be born in that most modern of nations — a land where the individual could ambition to reach the very heavens , cheered on by his compatriots: the United States of America.

Next: Go West, Young Man

Alex Buchet here…I’d like to take the opportunity to urge readers to seek out Conan Doyle’s wonderful non-Holmes fiction.

He is one of the founders of modern science-fiction through his Professor Challenger stories; among which ‘The Lost World’ has, in its own way, been as influential as the detective tales: ‘Jurassic Park’ would be unthinkable without its example; (Note that the sequel to JP was titled ‘The Lost World’.)

Anthony Burgess esteemed Doyle as the best writer of historical fiction in English after Walter Scott, and in this spirit I urge you to read ‘Sir Nigel’ and ‘The White Company’, marvelous novels set during the Hundred Years’ War between England and France. Doyle had a real gift for inhabiting the mentalities of bygone times.

He was also an incredibly prolific and masterly short-story writer; one of the early masters of horror fiction, who introduced the figure of the murderous Egyptian mummy, in the chilling ‘Lot 249’. Also a great parodist…

Yeah, you can say I’m high on Doyle.

The Lost World is so openly racist that I found it hard to love…though there are certainly some great set pieces. The pterodactyl nest is a lot of fun. And Professor Challenger is an entertaining character….

One of the greatest fictional detectives, who I didn’t see noted above, is Dostoevsky’s Inspector Porfiry from Crime and Punishment. He’s the archetypical deceptively bumbling detective, and the clear model for Columbo, played by Peter Falk, and Law & Order: Criminal Intent‘s Robert Goren, played by Vincent D’Onofrio.

Sherlock Holmes lives on, and when it comes to the best contemporary take on him, forget Robert Downey, Jr. (who’s a great Tony Stark, by the way). The 21st-Century Holmes is House, M.D., played by Hugh Laurie. He’s Holmes as a medical diagnostician, and the parallels are blatant, including the assholishness, drug addiction, and fetishistic approach to the epistemology of investigation.

Another nice read. One minor correction, though: I’m fairly certain Doyle lived for more than fourteen years.

Enjoyed this!

Whoops; thanks jeffrey. It’s fixed.

Noah:

“The Lost World is so openly racist that I found it hard to love…though there are certainly some great set pieces.”

Doyle’s attitude to race was ambiguous. You may note that in ‘The Lost World’ it’s a humorous but telling point that Challenger could physically be a member of the brutish, “evil” ape-men tribe.

As a young doctor in the Congo, and later as an older one during the Boer War, Doyle was angry and repelled by Europeans’ treatment of Africans. However, this didn’t invalidate for him his support for imperialism. His attitude seems very close to Kipling’s in this.

He did write a remarkable Holmes story, ‘The Adventure of the Yellow Face’, that is a stirring plea for so-called ‘miscegenation’, presenting as admirable and natural the marriage between an African-American man and a White woman. Read it here:

http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Yellow_Face

But as he aged Doyle became more and more racist, in public and in private. There is an appallingly ugly Black caricature of a thug threatening, then cringing before, Holmes — I’ve seen it quoted on neonazi websites.

Robert– actually Downey’s version of Holmes is not at all implausible, wearing scruffy Bohemian clothes, not shaving, a master prizefighter. And it is refreshing to see a slim, smart and handsome Watson: nothing in the series by Doyle contradicts this.

But you’re dead right about Dr House! In fact, as I recall, his apartment number is the same as that of Holmes’ house on Baker Street — 421 B!

Inspector Porfiry is a remarkable character, but he doesn’t really fit in with my brief here. But I do regret not mentioning the first real ‘superman’ detective: Edgar Allen Poe’s Chevalier Auguste Dupin, the direct ancestor of Holmes (as Doyle himself conceded.)

The fact that Challenger looks like them is used to mock him though, isn’t it?

I do enjoy lots of Doyle, and like I said there are good things in the Lost World. And I’m not denying that his take on race is interesting, or that it has nuance. It just sort of repelled me in this particular book, unfortunately.

Well, it mocks him but it also raises the question: what does ‘inferior’ signify?

still digging this series.

two things bug me about the Holmes stories:

(1) he’s using abductive reasoning, not deductive logic (a quibble, but it bugs me nonetheless)

(2) and therefore his predictions should be way, way more fallible than they turn out to be

I liked the way the recent films showed Holmes’ intellect manifesting itself in his fighting technique. It seemed like a clever solution to the problem of how you filmically show cleverness…but then, I have super-low standards for action movies.

I don’t think you need 1 in order to figure out 2.

Didn’t Umberto Eco write a novel base on your objections?

Maybe not a novel, but certainly an essay!

BTW it’s struck me belatedy, so sluggish are my thoughts — can’t ‘The Lost World’ be interpreted as an extended metaphor or allegory of colonial imperialism, not necessarily conscious (as opposed to Wells’ ‘The War of the Worlds’, which was a very conscious and deliberate metaphor/critique/satire of said colonial imperialism)?

well, if he were genuinely making “deductions”, there’d be no chance of error; his conclusions would be as certain as 2+2=4

Your linguistic rearguard action is sweet, Jones, but I think that’s a battle the logicians have lost.

I don’t know Noah—I don’t encounter many folks messing that one up.

Of course, I do mostly do math for a living, so my experience might be odd…

I think among most folks “deduction” is associated with detectives, rather than with math. Holmes changed the meaning, rail against it as you will….

I’m not railing! Just observing.

I actually don’t regret that my use of deduction has become a technical term. “Beg the question”—now that one bugs me. But my side has clearly lost there too.

“Exception that proves the rule” is an unfortunate one. “prove” there is supposed to mean “test” not “validate”, which is a fairly important distinction. Still, there’s something charming in the way the aphorism has enshrined illogic as common sense.

Actually, I don’t know when “deduction” came to have the sense it has in philosophy, so I don’t know whether Doyle was corrupting it or not. Come to think of it, mathematical induction isn’t induction in the formal logic sense, either.

But, yeah, “beg the question” has such a useful meaning in philosophy/rhetoric; it’s a real shame that its new broader sense has overtaken it.

Actually, Noah, the common interpretation of ‘the exception proves the rule’ is correct.

It’s not a principle of logic, but of Law. Suppose I grant you the right to hold a party on my land on such-and-such a date. Later, you try to hold a second party and I refuse. You take me to court, where you argue that I had given permission and never formally forbade me.

The court will note that the first party was allowed on a specified date. The very fact indicates that the permission was an exception.You cannot have an exception without a rule to be excepted from. Thus, the exception proves the rule.

It’s often used not in law but in logic, isn’t it? As in, “this thing doesn’t abide by what I’ve said, therefore it proves it.”

The law example seems like an instance where “proves” has its original meaning of “tests”.

No, it actually means ‘proves’ in the modern sense. In my example, we can gloss this as ‘there can be no exception to a rule unless there is said rule; therefore, the fact of an exception to a rule proves the existence of a rule.’

I do agree that the use in common discourse is often lazy and can be invoked to excuse logical lapses or unfair privilege.

From the Devil’s Dictionary:

“The exception proves the rule” is an expression constantly upon the lips of the ignorant, who parrot it from one another with never a thought of its absurdity. […] The malefactor who drew the meaning from this excellent dictum and substituted a contrary one of his own exerted an evil power which appears to be immortal.”

Ah, man; I love Ambrose Bierce. Nice citation, Jones.

I like Bierce very much, too, but on matters of English grammar, history, and usage he is a laughing-stock.

His book on the English language, ‘Write it Right’, is excepted from most of his bibliographies — it’s too embarrassing.