The index to the Indie Comics vs. Context roundtable is here.

____________

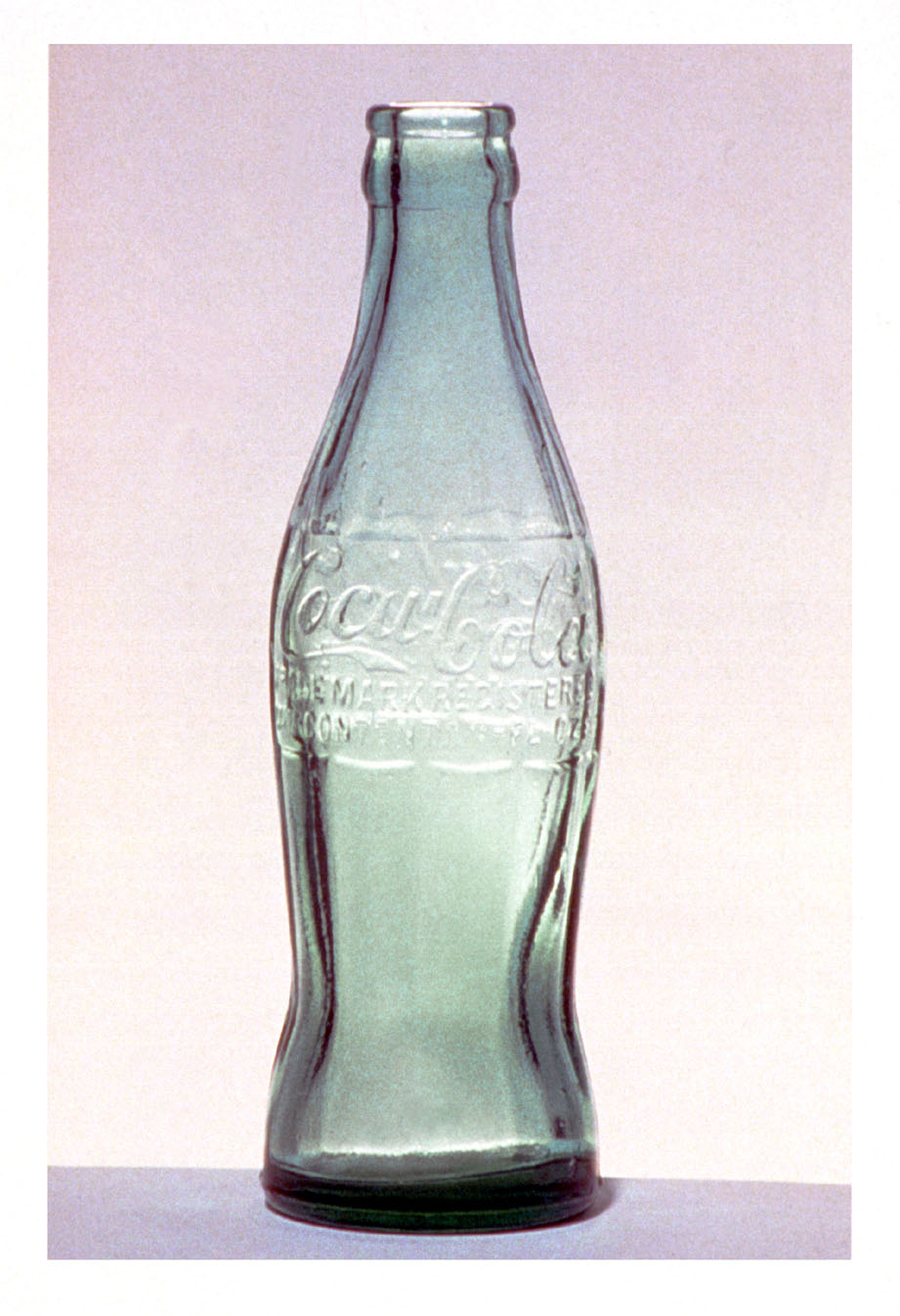

they smiled at ancient products, foregrounded in vain, and admired the display comparing a wasp-waisted cola bottle — so modestly pleased with itself — to a Flemish burgher kneeling before the Madonna, some centuries before Coca-Cola was invented.

That’s a passage from Gwyneth Jones’ Phoenix Cafe. The novel is set in the far future, after the alien Aleutians have arrived on earth. In this scene, an alien in a human body is touring the Tate with a human companion/lover, Misha. Mostly they look at old advertisements from our era, which were long ago admitted into museums as high art. Misha is himself an artist — and what he makes are a kind of marketing holograph; indie viral ads.

Visual art has embraced this to a large extent — which is why it’s funny and not implausible that at some point in the near future the Tate will have a television advertising collection. Catherine and Misha even have a fanciful conversation about the possibility of shit as an aesthetic experience. “That’s one of the least celebrated pleasures in life if you ask me, the feel of a lovely big fat turd plopping out of you. What’s art if it doesn’t venerate pleasure?” And yes, I’m sure Jones is familiar with Freudian discussions linking art and poop.

But while shit is art, novels for Catherine aren’t. For Aleutians, she explains,

The only use we have for printed words…is in instruction manuals. Art made in that medium would be like—um, asking your average human audience to admire a page of mathematical symbols. People do it from time to time, it’s done. Not by me.

I like the grammatical ambiguity at the end there. The “it” in “People do it” may refer to the way Aleutians viewing reading as art. Or it could refer to humans looking at mathematical symbols as art. Do humans ever look at mathematical symbols as art? Either way, enjoying the way that that question is or is not being asked is an aesthetic response. If this were to be read the way the Aleutians read, as an instruction manual, then the confusion of the antecedents is merely an error. Context determines art — not in the sense that you need context to understand art, but in the sense that you need context for there to be art at all.

In other words, any art can’t be art unless we say it is — and in large part it is art simply because we say it is, just as Catherine herself, born human, is an alien basically because everyone around her has decided that she is an alien. In this context, indie comics can’t be studied in anything other than context, because indie comics only exist, not just as a genre but as an aesthetic object, because context makes them so. Comics could be instructional manuals or science journal articles or advertisements — and indeed, you could see instruction manuals (with their diagrams) or science journal articles (with all those interesting visual notations) or print advertisements (image and text) as comics — perhaps even as indie comics given the right set of circumstances. There isn’t any outside to context; no way you can shrink down and look a the work in itself separate from your assumptions about the work, because the work as something to have assumptions about is made up of context.

And, for that matter, even your self speaking is a context, made up in part by the work you’re reading. Catherine is an Aleutian, she is part of that “we”, because of how she wouldn’t read the novel she is in. The art she looks at makes her who she is, and who she is makes the art she looks at. When Heidi says, “And yet, it does seem that indie comics and cartoonists are rarely examined in a larger contextual way. This is possibly because the content involves a lot of what some call introspection,” she is ignoring the fact that introspection is a context — and even a larger cultural one. Kailyn gets at this when she talks about how fandom is a context, but I think Jones goes even further, suggesting that even the recognition of context is linked to context — which perhaps explains why comics fandom and comics are so intertwined, depending on each other for the context that keeps them from disappearing.

If advertising and shit can be art and aliens can be human, it seems like a relatively minor act of perspective to see Phoenix Cafe itself as a comic; the text juxtaposed with coca-cola bottles and old advertisements, speaking to them in sequence. That comic is independent; it’s one you make in your head, the way that art for the Aleutians make poems which are actually pictures.

When another Aleutian comes along, maybe generations later, and ‘looks at my picture,’ the meaning of that moment to me is shed from the picture and enters the viewer. The poem is a communication-loop. Captured: and released again, not the same but evolved by everything that’s happened since, brought into being by my poems’ meeting with the new gaze.

Is this a poem? A comic? An information-loop? And what’s the antecedent of “this” anyway? The alien makes art, and the art makes an alien, in some confused future Tate, which is where we live.

_____

This may or may not be the last post in the roundtable, depending on who else sends me things in the next 24 hours or so. Either way, HU covers indie comics in context with some frequency, so we’ll revisit these issues again. This is a good point, though, to say thanks to all those who read, commented, and contributed. It’s been a really fun discussion.

Did you ever read George Dickie’s theories on art? Its a different spin on Danto’s… I think you’d really like both.

All this talk of context recalls the work I.A. Richards, who distinguished between context as co-text (the words around a word that give it meaning), and context as the prior uses of the word. Of course, a given reader will bring a different set of experiences with prior usage. These experiences are usually a mixture of direct, as in “I was called a geek all my life, hated it, and it really makes me mad when someone uses it in the positive,” and indirect, as in “It seems like geek was a pejorative until recently, now it just means someone who likes Joss Whedon and/or Apple products.” So when a person reads an article on “geek culture,” this person will bring both sets of experience to this new experience of reading, which is of course a new use of the word, which aforementioned person will interpret according to the co-text and context as a history of a word’s uses.

The take-away is that for every use of the word there’s a new context. Nevertheless, because we events (and text types) recur, certain words recur with them (“wretched” is a word I will forever associate with gothic fiction, and kryptonite with silver age comics), different readers will bring similar contexts to them. So while your reaction might be yours, if you’re having a reaction then odds are good that so too is somebody else.

That having been said, there are words (and if we’re talking comics, certain image types) that different groups experience in radically different ways. And to say this is to say more than “Hey, to each his/her/cis own.” It is to say that certain words and images are so freighted with prior use that my enjoyment of it is actually predicated on prior events that were deeply hurtful to another. So the thrill I might get from an instance of satire or transgression is not unearned, it’s just that I didn’t earn it, and somebody else did. Failure to acknowledge this is an ethical failure, and lazy criticism.

Thanks Nate and Kailyn! I’m glad somebody read this. You both should read Jones if you haven’t; she’s amazing.

And thanks for bringing her to my attention… I’m planning to grab the book from the library next time I’m there.

You should start with White Queen, first in the series (doesn’t make *that* much difference, but still.)

White Queen is one of those venerable classics of SF which I found a real chore to read. Probably the same way you feel about Dan Clowes in the sense that you can see her doing a number of clever things but it reads like the Pilgrim’s Progress of gender identity/studies. Which is why you like it I suppose.

Heh. I really love her. The second one, North Wind, is actually my favorite I think.

You should have written about the strange rape scene in White Queen (or maybe you have). And then the semi-rehabilitation of the rapist in a later book (?)

Haven’t written about that. And yes, Clavel is…I don’t know if rehabilitated is the right word. He (or sometimes she) is actually Catherine, who I talk about here. She decides to be born as a human woman in part to try to expiate the rape (which was of a man, who told her afterwards that he had treated him as a woman.)

Pingback: Bottle Personification Project | Andrea Szwejbka