The index to the Indie Comics vs. Context roundtable is here.

____________

“Ridicule or attack on any religious or racial group is never permissible.” – From General Standards Part C of the 1954 Code of the Comics Magazine Association of America

One of the consequences of the CMAA “Comics Code” of 1954 was that industry artists, writers, publishers, and distributors stopped taking risks when it came to race. At least, for a while. The slippery language of the “religion” section of General Standards Part C was broad enough that even the most tentative efforts to find an audience for increasingly complex, multi-dimensional images of blackness were scaled back. For several years, as the Civil Rights Movement transformed the social and political landscape of America, the mainstream comic book industry erred on the side of caution. (And I’m not just talking about those infamous beads of sweat.)

We know, of course, that the anxieties surrounding the Comics Code Authority’s strict guidelines opened up a space that mid-1960s underground comix would seek to fill. As Leonard Rifas states, “comix artists often tried to outdo each other in violating the hated Code’s restrictions,” deploying irony, satire, and caricature – notably, “extreme racial stereotypes” – to assert their freedom of expression.

In an interview from Ron Mann’s 1988 documentary Comic Book Confidential, R. Crumb explains:

We didn’t have anybody standing over us saying, “No, you can’t draw this. You can’t show this, you can’t make fun of Catholics… you can’t make fun of this or that.” We just drew whatever we wanted in the process. Of course we had to break every taboo first and get that over with, you know: drawing racist images, any sexual perversion that came to your mind, making fun of authority figures, all that. We had to get past all that and really get down to business.

Small press and indie comics creators continue to adhere to this countercultural checklist nearly sixty years later, gleefully undermining each new generation’s standards of good taste and decency with new artistic infractions. But Crumb’s approach to what he refers to as “absolute freedom” in the above quote does not adequately account for the risks taken by many African American artists and writers for whom the constraints, the taboos, and the violations differ. For me, then, examining indie comics and cartoonists in a larger contextual way means recognizing that there is more than just one Comics Code when it comes to race. And it means taking seriously the complex social and aesthetic tensions that black creators must navigate in order to exercise their own rights to free expression, even when they can’t get over or get past all that.

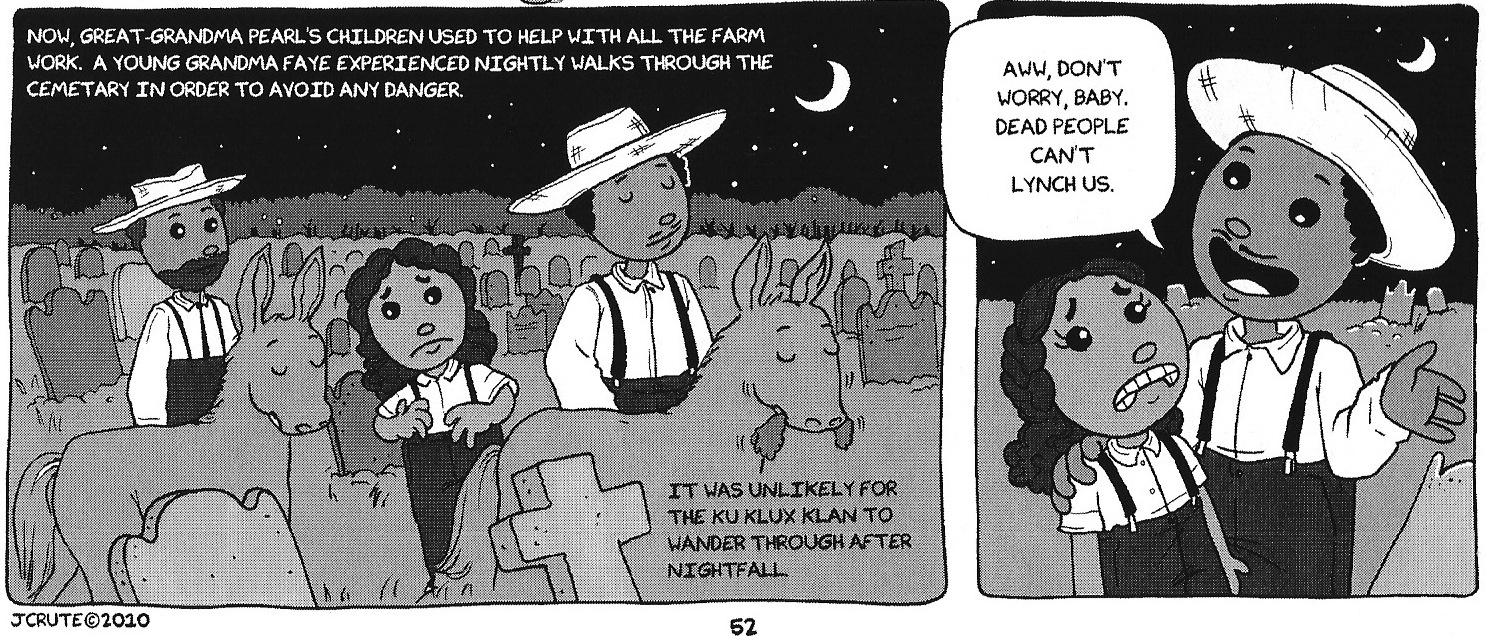

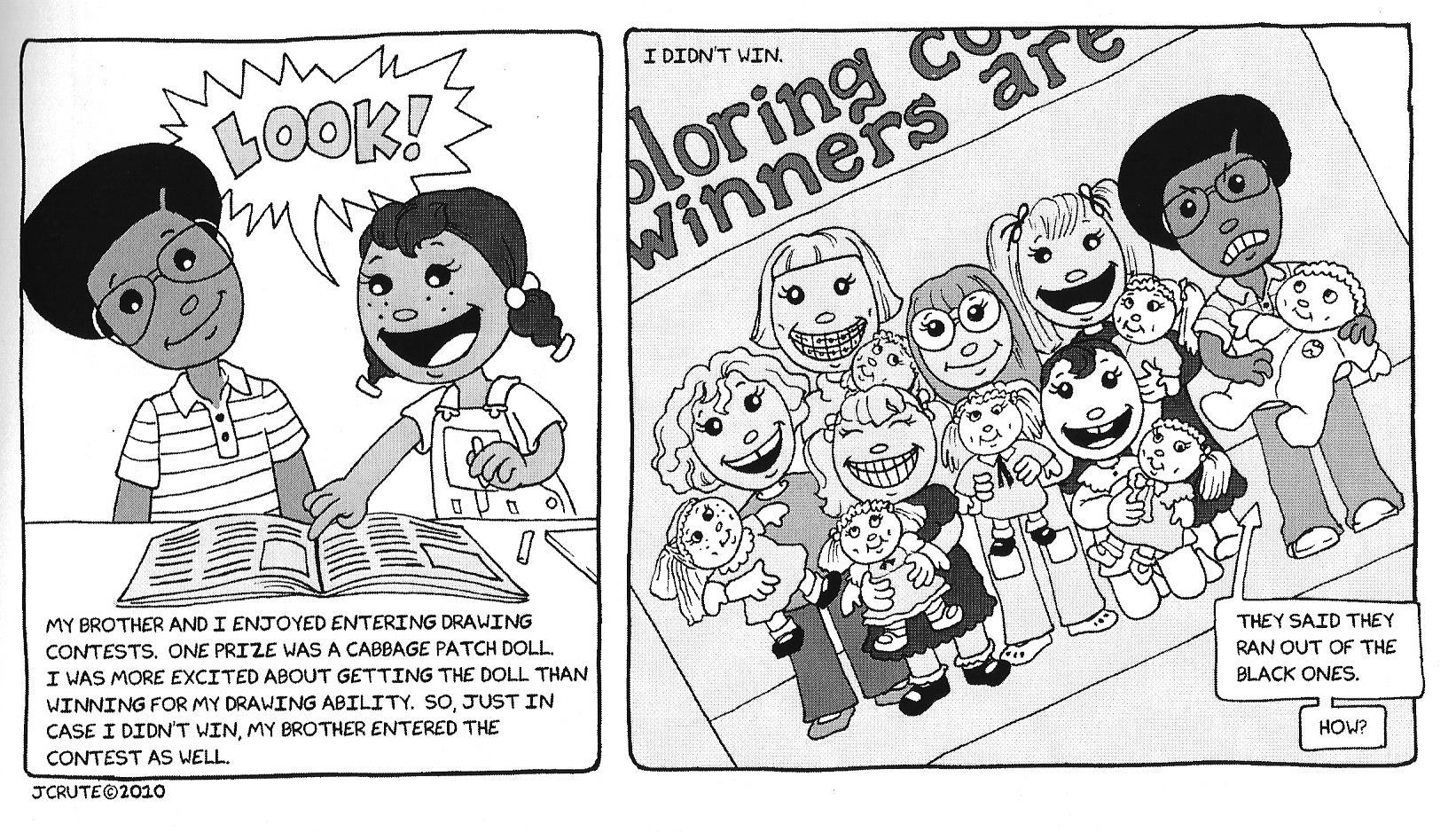

Cartoonist Barry Caldwell’s semi-autobiographical character Gilbert Nash is reprimanded in the 1970s strip above for making “kiddie garbage.” The regulating body standing over him in this instance belongs to an acquaintance that doubles as the physical manifestation of the cartoonist’s self-doubts. Her pointing fingers and exclamations intrude furiously into his drawing: “You should be out on the streets making great art about the black experience!”

Caldwell illustrates how an entrenched politics of racial respectability intersects with ongoing debates within black communities over the social function of art. Comics are derided by the woman in the strip as a frivolous medium through which white cartoonists are afforded the luxury of feelings, but a treacherous, irresponsible choice for a black artist with a greater obligation to his people. This is what is at stake when the chastising voice says, in other words: “No, you can’t draw this.” And yet four panels into exposing what is presumably a private exchange, Gilbert has already claimed his existence as a comic artist during the Black Arts Movement, rebuffing the viewer’s objectifying gaze with a question of his own. Taboo is drawing one’s self into being as an indie black cartoonist.

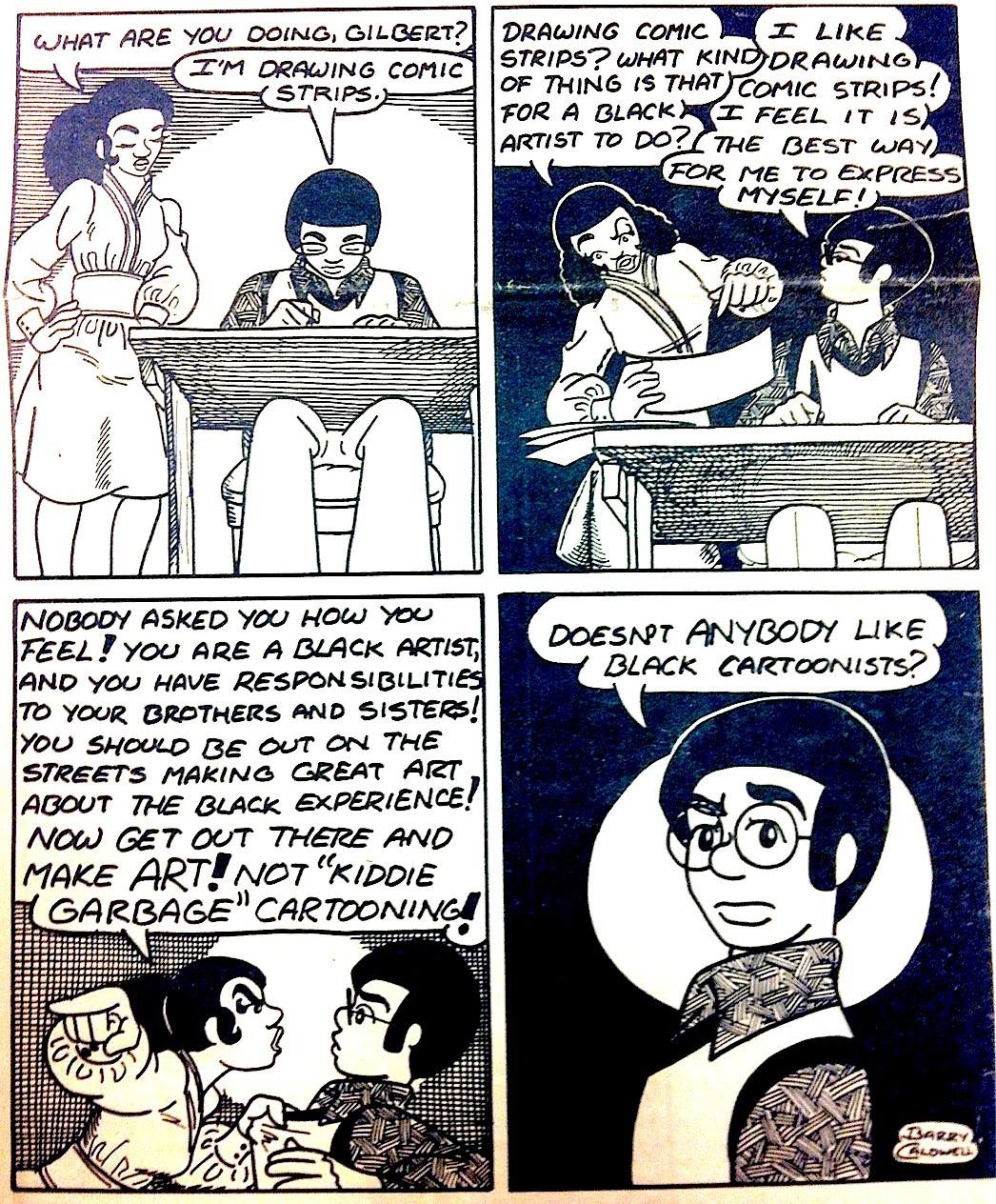

This is the context that shapes my reading of the comics of Jennifer Cruté. The two collected volumes of her comic strip, Jennifer’s Journal: The Life of a SubUrban Girl, feature autobiographical sketches of her upbringing in New Jersey suburbs as well as her life as a freelance illustrator in New York. With round, expressive black and white cartoon figures, Cruté’s characters appear to come from a charmed world where “ridicule or attack on any religious or racial group is never permissible.” The wide faces tilt back and break easily into open-mouthed grins and scowls. Her freckled persona wears teddy bear overalls, while an older brother’s Afro parts on the side, Gary Coleman-style. Like the cursive “I” that is dotted with hearts on the title page, the comic adopts a style more closely associated with the playfulness of a schoolgirl’s junior high notebook. The title foregrounds the space of socio-economic privilege and gentrification that her family occupies during the 1980s complete with Cabbage Patch Dolls, family vacations to Disney World, and copies of Ebony and Life side by side on the coffee table.

Race introduces a source of friction that impacts Cruté’s decision to represent her experience as a young black girl through caricature. There are plenty of comic strips that depict the lives of children, but much like Ollie Harrington, Jackie Ormes, or more recently, Aaron McGruder, Jennifer’s Journal uses children to explore the absurdity of racism and the means through which blackness is socially constructed. She traces her earliest affection for Kermit the Frog, for instance, to the episode of “The Muppet Show” when she mistook guest Harry Belafonte for puppeteer Jim Henson. And in scenes that take place down South, fears of lynching and racial violence dominate the story’s action, while the narrative turns to everyday micro-aggressions and more subtle humiliations to capture her own encounter with racism in the suburbs.

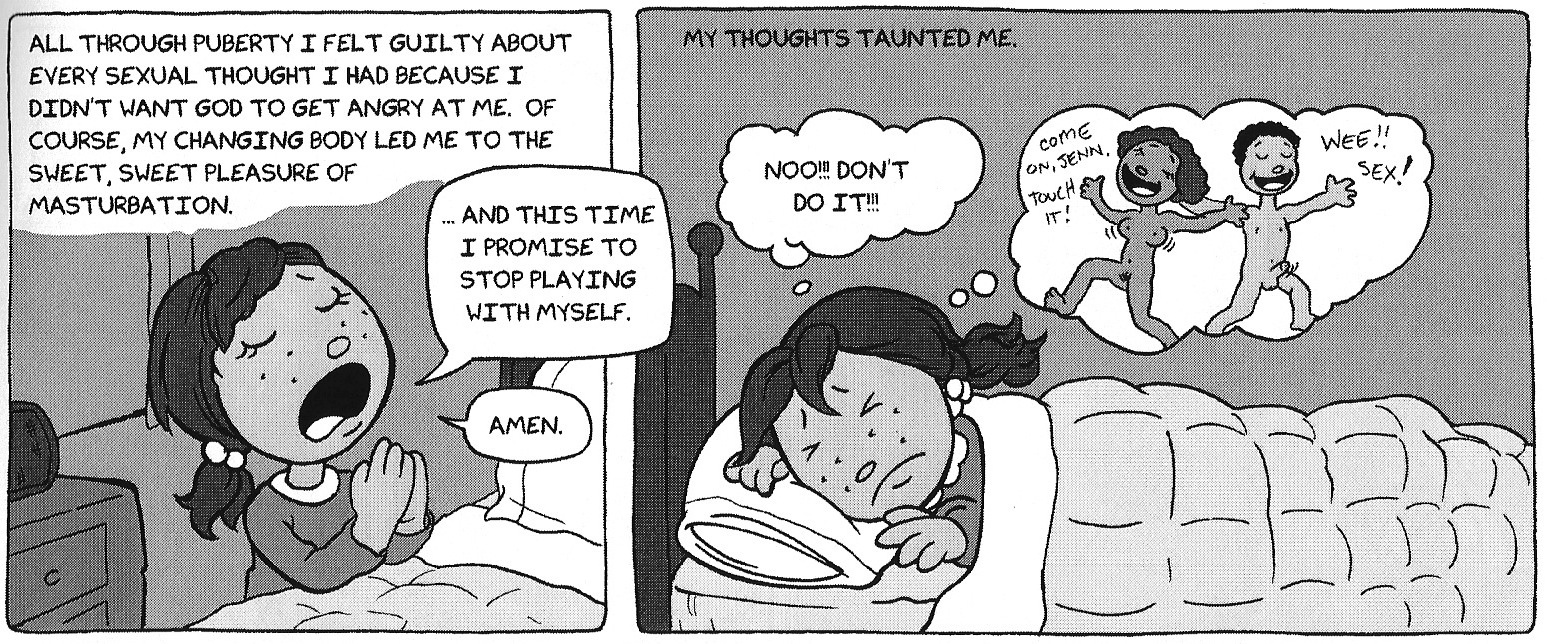

The first volume’s cover image further aligns Cruté’s work with the confessional mode of popular small press and indie comics; a young African American girl nervously pulls down the pants of a plush toy bunny, while surrounding her are other undressed stuffed animals posed in various sexual positions. The fact that young Jennifer’s inspiration comes from an art history book open to a painting of a nude Adam and Eve speaks to the notion that visual images have the power to confer an uninhibited sense of expressiveness and wicked curiosity. Likewise when her reflections turn to religion and sin, Cruté confesses her nightly struggle to abstain from masturbation. She portrays the temptation as she tries to go to sleep beneath a pictorial thought balloon that recalls the image from the book’s cover, although this time the nude Edenic bodies that entice her to “Come on, Jenn! Touch it!” are created in her own brown-skinned image.

My point here is that the push and pull of creative freedom and self-regulation play out in Jennifer’s Journal on multiple registers. Though warnings mark the front and back cover to alert readers that the book is “NOT recommended for children,” the comic’s aesthetic choices incorporate cautionary measures that gesture toward the kind of “instructive and wholesome” entertainment that the Comics Code Authority sought to preserve. In an author’s note, she writes: “I draw simple characters with round figures to soften the complex and contradictory life situations I depict.” But despite this stated intention, I can’t help but see a rewarding motley of signifiers in the comic – some that soften, others that rankle and surprise. The comic playfully mocks both the demand for racial respectability and the longing for a vision of reality that treats frank discussions about racism and sexuality as inappropriate.

I have tried to be careful not to suggest that black artists and writers are the only ones entitled to complex images of blackness in comics, nor are they the final arbiters of how best to represent and confront racism. As Darryl Ayo points out in his post about Benjamin Marra’s Lincoln Washington: “People are going to do what they’re going to do.” But as Darryl goes on to suggest, there should be a more meaningful, substantive awareness of historical context in our interpretations of comics that explore racial conflict. I believe we should also ask tougher questions about how and why particular notions of absolute freedom are idealized in underground, indie, and small press comics. And why there isn’t more room in these discussions for the “kiddie garbage” of Jennifer Cruté and the other creative risks that black comics creators are taking right now.

This isn’t a particularly substantive comment, but I just want to say that this is a great article and a breath of fresh air after so many painful discussions about race and transgression in comics. Thanks for writing it!

I was excited to read this, this morning too. This is a great direction to be exploring context…

Cruté’s work plays very transparently with the idea that ‘comics aren’t meant for children,’ in her style, her subject, and in the (probably needed) mature content warning on the cover. I’ll make sure to track down her work.

That Crumb quote above really annoys me. Its not a surprise coming from Crumb– the old boys club mentality that abusive, insensitive behavior is part of one’s eventual growth toward a fully realized person/artist, and that the ‘victimization’ of the cartoonist by the Code sort of warrants his reaction in victimizing other people. Psychologically true it might sort of, kind of be, but its a pig-headed myth, and I am so, so relieved for this piece in giving attention to other narratives of race and comics.

Thank you Quiana.

“The comic playfully mocks both the demand for racial respectability and the longing for a vision of reality that treats frank discussions about racism and sexuality as inappropriate.”

I was a little confused by this though, and want to read the work to see what you’re talking about. Couldn’t the gentle innocence of the drawing and narrative style also hint at a longing for a reality where these frank discussions of racism and sexuality are appropriate?

Great post, Qiana!

I was wondering if you’ve read Grass Green’s Super Soul Comix featuring Soul Brother American, his parody of both Captain America and (I think) some of Crumb’s excesses. In that comic, Green confronts superhero titles and underground comix of the 1970s simultaneously, exposing the parallels and the shortcomings of both. In doing so, he seems to suggest that Crumb’s work is less transgressive than it might appear to be, more inextricably tied to the racial representations of an earlier era, especially the Golden Age of the 1930s and 1940s.

Then again, he also clearly takes inspiration from both Crumb and from Jack Kirby, so he appears ambivalent and somewhat conflicted about his relationship to superhero titles and to the undergrounds.

I’d also love to hear more about Barry Caldwell’s work!

Kailyn, your confusion may be a result of my awkward phrasing….! Because I think we are on the same page. I was trying to suggest that Crute points to the world that the Code imagined would be “safe” and says that yes, even there, race and sexuality exist and we can/should have these difficult conversations. “Appropriateness” is definitely an idea under scrutiny and she appears to want to advocate for a new understanding of it. If you do have the chance to read one of her collections, I hope you’ll let me know what you think (and if I’ve missed the mark).

Brian, I’ve heard of Super Soul Comix but haven’t been able to get my hands on a copy. Trying to collect more of these references now. I’m still doing work on Caldwell too but it appears he may not have remained in comics for very long. He moved more into animation, apparently starting with Fat Albert and more recently, the Easter film, Hop.

Thanks for the feedback, Emily!

Brian hits on an important and interesting idea: it is possible to have a complicated relationship as a reader with an artist. Green was very obviously inspired by Crumb, who was in turn inspired by S. Clay Wilson’s id-inflected work. Wilson urged Crumb and the other underground artists to stop holding back and instead to draw every horrible thought and image they had in their minds. Doing so would allow them to fully unlock their potential.

I can kind of understand going through that step if I’m a certain kind of artist. However, that doesn’t mean that this “transgressive” art is any good, or even really transgressive in any meaningful sense. Green cleverly points out that the casual racism in many underground comics is very much like the racism of Golden Age comics. It doesn’t mean that Crumb isn’t a great and important artist, but it does mean that he shouldn’t get a free pass for every drawing he ever made. Personally, Crumb’s work didn’t really get interesting to me until he hit the Weirdo years, long after he worked that out of his system.

The problem, of course, that Daryl pointedly notes, is that these images don’t exist in a void. They come from a position of privilege and failing to understand and acknowledge that privilege is disingenuous. If an artist feels the need to work out racist imagery on the page, then it means that they acknowledge that racism truly exists and is something they are aware of. The question becomes using that awareness and owning it, rather than deflecting criticism on the grounds of “artistic freedom” or (ugh) “satire”. It’s not so much worrying about offending other people, but rather what it means to demean and alienate others, about “punching down” from a position of privilege.

I think much of Crumb’s work is vital, important and influential in a positive way. I also think much of it is juvenile, repulsive and not worth reading.

Looks like Caldwell has had a long and distinguished career in animation but I can’t find anything about his comics work. If you really wanted to know, you could always email him: http://www.blogger.com/profile/12865305912828890872

This sort of raises the issue of the way that comics continues to have a struggle with integration, both in terms of artists and in terms of representations? What is acceptable and what is transgressive seems especially pointed when, in terms of fame/influence/visibility, there are arguably more high profile artists who embrace racist iconography (Crumb, Winsor McCary, Herge….) than high profile black cartoonists That’s really not the case in something like popular music (and the issue is at least more complicated in television or film or literature.) Not that there aren’t important black cartoonists; I’m just often struck by comics’ history of segregation, which seems extreme even by the standards of other not all that enlightened pop culture forms, and makes the underground’s claims about transgression via racism seem especially strained.

Bearing in mind that the comic many consider the greatest ever made was created by a black man.

Yes; Herriman’s sort of the exception that proves the rule. I don’t think it necessarily changes what I said though.

Country music is maybe an interesting comparison. There are important black country performers (Charley Pride, Ray Charles), but they don’t really change country’s overarching commitment to selling images of whiteness. (Pride is a singular exception; Ray Charles isn’t considered a country artist.) Comics isn’t ideologically committed to whiteness in the same way; the segregation seems more ad hoc than essential. But I think Herriman’s blackness often functions rhetorically within comics as a means of authentication/validation rather than as a spur to challenging the overall narrative in which racist creators are a lot more central than black ones.

I don’t know…maybe I’m derailing the thread here. I thought the point about the politics of respectability was super interesting too, and a point where there might be a space for Herriman but isn’t (at least in that strip.) I mean, you could see a conversation in which someone says, “black people shouldn’t do kiddie garbage cartooning!” and a black cartoonist responds by talking about George Herriman. Maybe that does happen some places? But maybe also Herriman’s isolation in the canon has made him somewhat hard to use as a resource for black cartoonists?

Or maybe I don’t know what I’m talking about? Qiana? Somebody? Help?

Integration does mean “equal access” to all art forms but I’m not surprised it’s not pushed that hard in comics considering the art form’s poor economic viability.

The situation looks a bit better if you consider the new TV season. Almost all of these are headed up by white actors (except for the new and apparently not improved Ironside), but there are a number of black + latino actors/actresses in Brooklyn Nine Nine and Sleepy Hollow. Even Agents of SHIELD’s seemingly white parade has a couple of Chinese actresses. Which will inevitably lead to suspicions that they’re trying to sell it to China I suppose.

I go back and forth on Herriman – it’s rewarding to position him as a kind of ancestor figure for African American cartoonists, regardless of how he identified himself. But celebrations of his blackness can only go so far for me. I like Jeet Heer’s take on this ambivalence in his intro to one of the Krazy Kat reprints.

Noah, the question you ask about comics and integration reminds me of a related problem in literary criticism where the interests of black authors are regarded as provincial and particular – and therefore not relevant to non-black readers – while the work of white authors are admired for their universal themes and timeless qualities. And when white authors address racial issues, it is by choice and as a result of careful craftsmanship whereas black authors are simply writing about “what they know.” Reviewers and critics promote these false distinctions, so do anthologies and bookstores, so do course syllabi… I think there is a correlation here when it comes to the assumptions made about black and white cartoonists too.

Matt, thanks for the link to Barry Caldwell’s info. I found his blog too and sent him an email last weekend asking about the origin of his strip. (I stumbled across it in some archives but it was a clipping that had no source information.) He hasn’t written back unfortunately.

So Herriman identified as white? I sort of knew that, but wasn’t sure (this is what I mean when I say I don’t know what I’m talking about.)

Anyway (to try to talk about something I have a slightly firmer grasp on) I think it is analogous to literary criticism — though there’s a much stronger tradition/history/discussion of black figures in literature. Toni Morrison is hugely important; people like Ralph Ellison and James Baldwin and Richard Wright are firmly canonical. My sense is that comics isn’t even to that point yet. And as you say, race is central to major canonical American literature (Huck Finn, Stephen Crane, Faulkner), which may be problematic as you say, and doesn’t mean that racism doesn’t exist, but does create a narrative in which Toni Morrison can be central rather than peripheral (not that there aren’t important black comics creators, but that the canon isn’t configured in a way that they can matter the way Toni Morrison does, except for Herriman, who kind of proves the point). Same in a different way with television; as Suat says, there’s an established tradition/expectation of tokenism, which certainly isn’t what you’d call good in any way, but still looks relatively progressive compared to comics, which often seems to struggle to manage even that kind of backhanded representation.

Does it really matter that Herriman wanted to hide his racial identity?

Does his work need to be distinctly “black” (whatever that means) for it to count? Because it would be a pretty constrictive existence if *all* black authors felt compelled to do only race-related material or comics which dealt specifically with the black experience. I understand that it’s an indelible aspect of their lives and they’re ideally suited to write about both of these matters though. I feel the same way about Asian American authors. For a long time during the 80s, I had no idea that Trevor von Eeden was black (for example).

In line with Qiana’s views on the lit crit scene, there are some writers out there who feel that Herriman’s blackness is over emphasized (!)

Anyway, to what do most academics attribute the nonsense poetry/dialogue in Krazy Kat nowadays?

The thing is that race is a social construct in a lot of ways. If you decide to be white, and other folks treat you as white, there’s a non-trivial sense in which you’re white. In which case claiming him as a black artist becomes, not impossible, but complicated.

Or at least that would be one take. Is that where Jeet’s coming from, Qiana?

I’m hesitant to write much about Herriman until Michael Tisserand’s biography (which will revolutionize our understanding of the creator of Krazy Kat) is published. But suffice to say, Herriman wouldn’t have had the career he had if he weren’t able to pass as white. If he had been a few shades darker he wouldn’t have worked for the Hearst press but maybe, if he were lucky, for one of the black newspapers (which means his work wouldn’t have had anything like the visibility it actually had). So I think Herriman’s biography reinforces rather than contradicts Noah’s point about comics being very segregated historically. The proviso I would make is that this segregation should be located in the context of the newspaper industry (when we’re talking about comic strips) and pulp publishing (when talking about comic books). I’d have to do more research on it, but my impression is that comic books were actually less segregated in the 1930s/1940s than many other aspects of commercial publishing. Would Matt Baker have had the career he enjoyed in comics if he had gone into commercial illustration in the 1940s? Also, discussions of ethnic diversity have to take into account that whiteness (and blackness) aren’t stable categories but shift over time. Was Will Eisner or Jack Kirby “white” in the 1930s? Was Tad Dorgan “white” in the early 20th century? If we extend ethnic diversity to included immigrants, then I’d argue that the diversity of comics peaked in the 1930s and 1940s. Comics are in some ways a much “whiter” field now than they were in the the 1940s.

Have nothing to add to Qiana Whitted article except to note that it’s excellent.

“If you decide to be white, and other folks treat you as white, there’s a non-trivial sense in which you’re white.”

That might work out if Herriman was some sort of Kasper Hauser-like figure. But since he spent a lot of his life trying to hide his race and apparently his curly hair with a hat, you have to think that he knew that his public life was, in part, a sham. Being able to pass and acting the part for the sake of doing what you love is not exactly the same as being white.

This discussion of Herriman’s ‘blackness’ reminds me uneasily of the American take on race: “one drop of blood” makes you black.

Herriman was, in fact, as much white as black. So are Barak Obama, Halle Berry, Jennifer Beals.

In France,and generally in Europe, at most such mixed-race individuals would be called “métisse”. Witness the examples of Alexandre Dumas and Pushkin — both of whom not only made no effort to conceal their part-black ancestry, but actually boasted of it.

Yet they self-identified as white, and the world went along. Europe is as racist as America in its own ways, but there’s no real concept of “passing” as applied to Blacks.(Jews are another matter– vide the “Marranos” of Spain.)

BTW, passing was not denigrated by Blacks of a hundred years ago, as it is today. On the contrary, it was seen as an almost revolutionary act — sticking it to the Man through trickery.

Suat, to some extent. And the experience of passing is definitely a part of African-American experience (James Weldon Johnson’s “Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man” being the classic text, I think.) But still, even actively passing isn’t necessarily a sham. Trans folks who work to be seen as one gender are arguably trying to be taken as what they are, rather than being mistaken for what they’re not. Reifying race as authentic despite social markers or self-identification is problematic inasmuch as it makes race the most real thing about you, and so mirrors the logic of racism (in which race is determinative).

Again, I’m not saying that Herriman can’t be seen as black. I’m just saying that it’s a somewhat complicated issue, and (as Qiana says) makes it tricky to figure him unproblematically in a tradition of black cartooning (it seems like.)

Jeet, that’s a really interesting point about the relationship between ethnicity and race. I tend to think there are parallels between prejudice against ethnics and racism in the US, but there are also important differences, such that seeing Jews as “black” in the past doesn’t quite capture what’s going on. There was certainly anti-Semitism…but anti-Semitism and racism don’t always match up (Walter Benn Michaels talks about how some racists were very pro-Jewish in the U.S.) The fact that comics was very open to Jews…did that make it more open to black creators (as you somewhat suggest?) Or less open? I don’t think it’s always clear.

Hi Noah,

When talking about Herriman it might be useful to quickly go over the known facts. My introduction to the Krazy and Ignatz volume for 1935-1936 covers the evidence up to now (as I said Tisserand’s biography will render what I wrote obsolete). Here’s a link on Amazon which should let you read my intro: http://www.amazon.com/Krazy-Ignatz-1935-1936-Warmth-Chromatic/dp/156097690X/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1382113228&sr=8-1&keywords=krazy+ignatz+jeet

Basically, I would say the salient points when thinking about this are:

1) Race is a social rather than a biological fact. The social reality of race comes not just from how people are designated by society (labeling theory) but also by how they subjectively experience social reality.

2) In Herriman’s case, the salient point to consider is that his family in the 19th century thrived in the particular social context of the “free people of color” in New Orleans. This social formation, under the pressures of segregation in the late 19th century, was under increasing threat and Herriman’s family moved to Los Angeles where they passed for white.

3) What makes Herriman’s family background relevant is that there is considerable evidence in Krazy Kat that his family’s experience with race is a formative part of Herriman’s sensibility. The fluidity of race and the ambiguity of identity are major thematic concerns in Herriman’s work.

4). It’s not quite true to say that Herriman publicly identified as white. Rather he was very cagey about taking about his background and let people get a variety of impressions. He was variously described as French, Greek, Irish and Turkish (among others!) I.e. he created the impression of an exotic, non-WASP background.

5). It’s fair to say that publicly Herriman didn’t identify as Black. But his subjective self-identification is much more complex. I’ll return to point #3 and suggest that he had a much more fluid notion of racial identity than was common in his era (or our own era, for that matter).

6). The question of passing has to be historicized. During Herriman’s lifetime, passing was often celebrated by Black writers, as a form of trickery and cleverness. This attitude made sense given the pervasive power of the racial dividing line in that era: if Blacks as a race were stuck behind the color line, individual Blacks could, like guerrillas, make incursions across the line by passing. The attitude towards passing changed in the 1950s and 1960s when the civil rights movement started to pick up steam. At that point, passing started to be seen as a betrayal of authentic identity and harmful to the collective efforts to improve the conditions of Blacks.

About the ethnic pluralism within the comic book industry, I just want to clarify that I wasn’t saying that anti-Semitism and racism are homologous or that the presence of what we would call “white ethnics” meant that there was no racism in the industry (quite the reverse, actually, ethnic ghettos can be exclusive). Rather my point was that we shouldn’t see the comic book industry as white in our sense of the word. In the social world of the 1930s, a lily white industry would be advertising or even academia (Lionel Trilling was either the first or second Jewish teacher hired at Columbia). Comic books weren’t white in that way.

Yeah; I understood that was what you were saying. Didn’t mean to imply otherwise.

Again the country music analogy is interesting, maybe? Country music’s struggle with race is related in part to its subcultural Southern identity. There may be something similar or parallel happening with comics’ tradition/history as a subculture, in terms of first ethnic and then geek identity? Lots of differences obviously (most notably the fact that white southern subcultural identity is strongly historically linked to racism) but perhaps some similarities as well.

I am really enjoying this thread and I can’t wait for the new Tisserand biography.

I began my African American comics class this semester with Herriman and not because I wanted the students to decide if he was black, but so that they could have exactly the conversation we are having right now. I wanted them to know that regardless of how the census identified him or how he self-identified in public or private, he’s part of comics history AND part of a black cultural tradition in which the range of affiliations, orientations, investments vary. I am also very persuaded by #3 on Jeet’s list – “the fluidity of race and the ambiguity of identity” in works like Krazy Kat (and Musical Mose) makes his background relevant but not prescriptive for me.

Noah’s already mentioned “Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man” and its themes of passing, identity, and social access but in thinking about Herriman, I like Colson Whitehead’s more recent, “The Intuitionist” (anybody read that?) – in which hidden racial strife on the part of one of the “founding fathers” of an industry ended up shaping its very foundations, unbeknownst to his followers (the industry in this case being elevators).

I can’t speak to the country music analogy, but the comparison makes me think that we should probably be more precise in specifying genres when evaluating how segregated the comics industry is (in terms of the creators and the representations). For instance, superhero comics may be the most visibly “integrated” but that is not in my opinion where the best work by black comics writers/artists is being done today.

Superheroes has its problems too though in terms of representation. I just think of JLA cartoons where they’re always using John Stewart as Green Lantern, essentially because they need more diversity for television than is the default in comics.(Where Stewart is a tertiary character at best.)

Oh, and thanks for that post trying to bring me up to speed, Jeet. I appreciate it — and really fascinating information.

Hi Jeet!

I agree up and down the line, except fro your statements about passing in the first decades of the century. It seems a bit much to state that it was “celebrated by Black writers, as a form of trickery and cleverness.”

I would say that many writers of the period found it to be an topic of interest, even obsession. However, the dilemma of passing was hardly an area for dismantling-the-master’s-house celebration, at least if you consider how it is represented in the literature of Johnson; Chesnutt (House Behind the Cedars); Fauset (Plum Bun); Schuyler (Black No More); and even Larsen (Passing). Passing, in all these works, remains morally, politically, and psychologically problematic — and in many a work, impossible. If Herriman was reading these books, he would have been encountering fiction that called into question his courage, rectitude, allegiance, and self-image.

(Of course, the same books interrogate the very idea of racial identity, image, and allegiance.)

Agree that what’s key here is the way that Herriman is part of “comics history AND part of a black cultural tradition”. In terms of that tradition, the appropriation or affiliation of Herriman’s work by Black creators after his death is relevant. Ishmael Reed’s Mumbo Jumbo being the best example.

I would also add that Herriman’s work can be linked to the wider American (or Western) discourse on race. Animal allegories have a strong racial component going back to at least the 19th century (if not further back to Aesop) and forward to Disney and Warner Brothers. Herriman’s strong influence on Disney and the coded “blackness” of Mickey Mouse is part of the story.

@Peter Sattler. Yeah, you’re right, I was too glib in my comments about how passing was seen. There was always a sense of it as a fraught enterprise. On the other hand, there were articles in the black press in the early 20th century celebrating passing, something that became much less frequent in the 1950s. My friend Megan Kelley has written about this in her doctoral thesis.

I need to look more into the press. (When you teach lit, you tend to think entirely about writing as lit.)

Of course, if Herriman were “deeply” passing, it’s unlikely he would have spent time reading any of these things.

Can’t wait for the Herriman bio to shed more on all these matters as a part of the man’s daily and professional lives.

Excellent article, Qiana, and an interesting discussion from everyone else.

Those interested in the treatment of passing in American letters over the decades might want to check into Kathleen Pfeiffer’s Race Passing and American Individualism, which includes chapters on Ex-Colored Man, Frances Watkins Harper’sIola Leroy, William Dean Howells’ An Imperative Duty, Jessie Fauset’s Plum Bun, Nella Larsen’s Passing, and autobiographical essays by Cane author Jean Toomer. The book also includes a discussion of Roth’s The Human Stain as well.

Parts, including the introduction, can be read at Google Books. Here’s the link:

http://books.google.com/books?id=XLxL71MPWhoC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

Oh, just a head’s up: It doesn’t deal with Herriman at any point.

I’d like to add another text to this discussion of the complexities of passing in the early 20th century, Oscar Micheaux’s 1932 film Veiled Aristocrats. It is one of his earliest sound films and the second of his three adaptations of Chesnutt’s The House Behind the Cedars. In the 1932 version, Micheaux turns Rena Walden’s plight into a musical and saves her from the fate she meets in the novel. Three characters at the end of the film also engage in a long debate about the dangers of passing–before the musical sequence begins!

It’s one of his best films, despite the incomplete, fragmented version that has survived. In their excellent study of Micheaux’s novels & films, Pearl Bowser & Louise Spence offer an interesting critique of the movie and its response to the larger debates about passing in the urban African American community of the era.

Pingback: Yes, Comics Can Empower Black Girls! | Fledgling