Marvel Comics’ She-Hulk is perhaps the most high-profile of their many female characters that are derivative of successful pre-existing male characters. However, three decades since she first appeared in Savage She-Hulk #1, writers (especially John Byrne) have worked to develop the character into someone who is not merely a shadow of a male character with no defining personality or history of her own in titles like The Avengers, Fantastic Four and eventually her second solo book, The Sensational She-Hulk. In fact, by the time Dan Slott got around to writing her solo title in 2005, the character’s winking reference to her own status as a comic book character became one of her defining features, and Slott developed this into a knowing and charming run, that while not free of problems, represents some of Marvel’s best output in the 21st century.

At the heart of Dan Slott’s run on what are referred to as She-Hulk volumes 1 & 2 (despite being the 3rd and 4th volumes of She-Hulk titles) is an alternately critical and nostalgic concern with the subjects of continuity and rupture in serialized superhero comic book narratives. Slott uses the space of a marginal title that probably never sold very well to undertake a meta-narrative project that is as much enmeshed in the insularity of the mainstream comics world (what many people refer to as “continuity porn”) as it is a critique of such obsessions.

At the heart of Dan Slott’s run on what are referred to as She-Hulk volumes 1 & 2 (despite being the 3rd and 4th volumes of She-Hulk titles) is an alternately critical and nostalgic concern with the subjects of continuity and rupture in serialized superhero comic book narratives. Slott uses the space of a marginal title that probably never sold very well to undertake a meta-narrative project that is as much enmeshed in the insularity of the mainstream comics world (what many people refer to as “continuity porn”) as it is a critique of such obsessions.

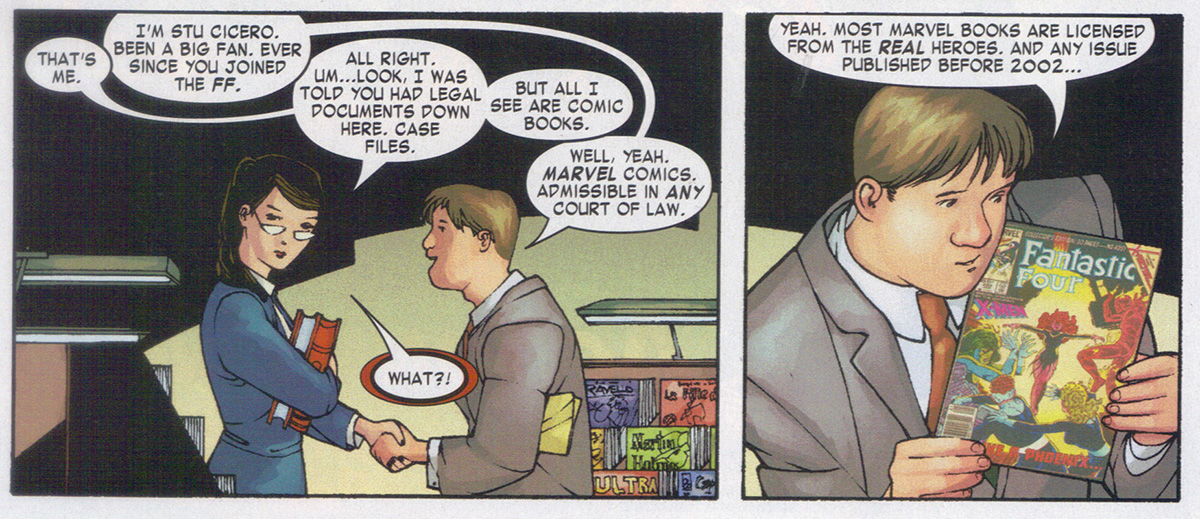

There is a sense of adult whimsy that really helps to keep this run afloat. Some comics critics, like Jeet Heer, may claim that “superheroes for adults is like porn for kids” (in other words, a bad idea) or that it is time to abandon superheroes altogether, but I think Slott’s work here proves that wrong, as it eschews the self-serious attitude of typical post-Watchmen/Dark Knight “adult” superhero comics in favor of embracing the ridiculousness of the genre that is best appreciated by long-time fans who have learned to have a sense of humor about their beloved Marvel comics stories. Aiding She-Hulk in this meta-project is Stu Cicero, who often seems to be a mouthpiece for Slott himself, though that kind of problematic direct voicing of the author’s position on the tradition of superhero comics is often skewered by the series’ afore-mentioned sense of humor.

Stu works in the law library at Goodman, Lieber, Kurtzberg & Holliway, where the majority of the action in Slott’s two She-Hulk runs occurs. Jennifer Walters aka She-Hulk begins working at this firm that specializes in “super-human law” after losing her job as an assistant D.A. (all the times she helped to save the world left all the cases she tried susceptible to appeal as owing her their lives effectively prejudices all juries) and then being kicked out of Avengers’ Mansion for her irresponsible hard-partying ways. Her new boss’s insistence that she work in her civilian guise of Jennifer Walters means her identity as She-Hulk won’t compromise her cases. Furthermore, her connections to the superhero community would be helpful in drawing new clients.

As a law firm that specializes in trying cases involving superhumans, one of its greatest assets is the comic book section of its law library. The conceit in these series is that Marvel Comics exist within the Marvel Universe (something that has been established since the very early days—Johnny Storm is shown reading a Hulk comic back in Fantastic Four #5 and the Marvel Bullpen has been depicted in various titles countless times), telling the “true” stories of the adventures of Marvel superheroes. Stamped by the Comics Code Authority, “a Federal Agency,” they are admissible as evidence in court. Now, this is of course ridiculous. The Comics Code Authority was never a federal agency, but even more absurd is the idea that comic books would ever be taken so seriously. How could anyone expect the stuff depicted in comics between 1961 and 2002 to be internally consistent? How can anyone expect that everything printed in a Marvel Comic, down to the most obscure detail be made to jive with every other thing as to be of value in a trial or lawsuit? But therein lies what makes this run of She-Hulk so great. The comic has a lot of respect and attention to the minute convolutions of Marvel Comic history—one might even go so far to say it has a reverence for them—while never forgetting they are just funny books. The fun is in engaging with the stories to find ways as fans to make sense of it all (or just make fun of the fact that it doesn’t make sense), but not to take it all so seriously that you come off as if trying to argue a federal case from comic books.

It is with this conceit, tongue planted firmly in cheek and the ability to comment on the very kind of comics that She-Hulk is an example of firmly enmeshed into its narratives, that Slott is able to get away with a lot. Foremost, among these things is to examine the role of sex and She-Hulk’s sexuality in her past and the way it has shaped views of her character. This is not free of problems and I am conflicted about how it is depicted, but it does not wholly undermine the project. While I appreciate the frank discussion of She-Hulk’s sexual appetites and the effort later to directly address and rehabilitate the adolescent approach to sex common to this whole genre of comics, there is a bit of slut-shaming going on and more than one gratuitous scene that is in line with the sexualized objectification of the She-Hulk character and her Amazonian voluptuousness. In other words, like many attempts at satire, this comic sometimes crosses the line into being what it seems to want to be commenting on. (But this is not just a problem with mainstream superhero comics—as much as I love Love and Rockets, I sometimes get the same feeling from Gilbert Hernandez’s work). It is for this reason that Juan Bobillo’s pencils seems to serve Slott’s series the best. It has a kind of soft rounded cartoony look that makes She-Hulk look a little chubby and cute in both her incarnations (more Maggie Chascarillo than Penny Century) and that gives the series’ whimsy a visual resonance. The rest of the artists on the series vary in their skill and appropriateness to the material and sometimes fall into the questionable range of Heavy Metal-like cheesecake.

It is with this conceit, tongue planted firmly in cheek and the ability to comment on the very kind of comics that She-Hulk is an example of firmly enmeshed into its narratives, that Slott is able to get away with a lot. Foremost, among these things is to examine the role of sex and She-Hulk’s sexuality in her past and the way it has shaped views of her character. This is not free of problems and I am conflicted about how it is depicted, but it does not wholly undermine the project. While I appreciate the frank discussion of She-Hulk’s sexual appetites and the effort later to directly address and rehabilitate the adolescent approach to sex common to this whole genre of comics, there is a bit of slut-shaming going on and more than one gratuitous scene that is in line with the sexualized objectification of the She-Hulk character and her Amazonian voluptuousness. In other words, like many attempts at satire, this comic sometimes crosses the line into being what it seems to want to be commenting on. (But this is not just a problem with mainstream superhero comics—as much as I love Love and Rockets, I sometimes get the same feeling from Gilbert Hernandez’s work). It is for this reason that Juan Bobillo’s pencils seems to serve Slott’s series the best. It has a kind of soft rounded cartoony look that makes She-Hulk look a little chubby and cute in both her incarnations (more Maggie Chascarillo than Penny Century) and that gives the series’ whimsy a visual resonance. The rest of the artists on the series vary in their skill and appropriateness to the material and sometimes fall into the questionable range of Heavy Metal-like cheesecake.

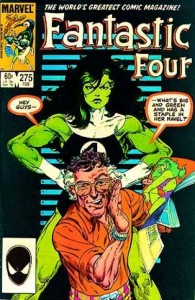

The meta-fictional aspect of this She-Hulk run is one that has its origins in the first printing of her story, as the only reason she even exists is that Stan Lee, worried that CBS would use the success of The Incredible Hulk TV show to create a female version of the character, rushed one to print first in order to claim the trademark on her. From her first appearance, she served a meta-purpose—not the purpose of a story that needed telling or that was even necessarily worth telling, but the purpose of protecting control of a brand. That first series—Savage She-Hulk (1980-82)—demonstrates that in its weakness. The Sensational She-Hulk, (1989-94) written and drawn in part by John Byrne is by most accounts a lot better. I have only ever read a handful of its issues (they are on what I call my “all-time pull list”), but one of the things that is notable about the series is She-Hulk’s tendency to directly address the reader, breaking the fourth wall, so to speak. She often acts as if she knows she is in a comic—but even more often than that she is frequently depicted in various forms of wardrobe distress. There is also a whole issue of Fantastic Four (#275—also written by Byrne) that centers around her efforts to stop a tabloid publisher (depicted, not coincidentally, to look like Stan Lee) from going to print with nude photos of the emerald giantess, taken from helicopter as she sunbathed on the roof of the Baxter Building.

The meta-fictional aspect of this She-Hulk run is one that has its origins in the first printing of her story, as the only reason she even exists is that Stan Lee, worried that CBS would use the success of The Incredible Hulk TV show to create a female version of the character, rushed one to print first in order to claim the trademark on her. From her first appearance, she served a meta-purpose—not the purpose of a story that needed telling or that was even necessarily worth telling, but the purpose of protecting control of a brand. That first series—Savage She-Hulk (1980-82)—demonstrates that in its weakness. The Sensational She-Hulk, (1989-94) written and drawn in part by John Byrne is by most accounts a lot better. I have only ever read a handful of its issues (they are on what I call my “all-time pull list”), but one of the things that is notable about the series is She-Hulk’s tendency to directly address the reader, breaking the fourth wall, so to speak. She often acts as if she knows she is in a comic—but even more often than that she is frequently depicted in various forms of wardrobe distress. There is also a whole issue of Fantastic Four (#275—also written by Byrne) that centers around her efforts to stop a tabloid publisher (depicted, not coincidentally, to look like Stan Lee) from going to print with nude photos of the emerald giantess, taken from helicopter as she sunbathed on the roof of the Baxter Building.

While not part of her original conception, unlike her cousin Bruce Banner/The Hulk, Jennifer Walters/She-Hulk’s transformation seems to have a lot more to do with uninhibited sexuality and sexual appetite than with anger. Sure, She-Hulk gets mad and smashes stuff, but since for the most part she can control her transformation and even prefers her She-Hulk identity and remains in it most of the time (for months or years at a time), anger has less to do with it than her desire. Slott’s run on the title explores a key part of that desire—Jennifer Walters’s desire to escape her petite less assertive human form. Jennifer Walters has the typical social inhibitions, especially ones that are used to deny ourselves pleasure and immediate gratification (for good or ill), while for the most part, She-Hulk has no such compunctions.

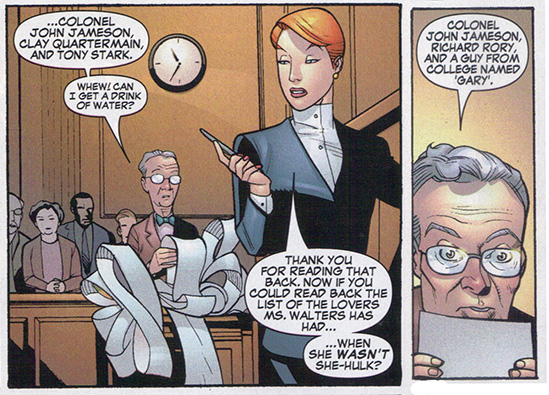

As such, the fact that She-Hulk engages in lots of casual sex becomes a defining part of her character and a conflict within the comic (her bringing home a string of men without proper security clearance to the Avenger Mansion for one-night stands is part of what gets her kicked out). It is a problematic, but fascinating aspect—on the one hand, explicitly addressing sex and sexuality is something Marvel comics hardly ever do in a way that could be considered mature (and by mature, I don’t mean humorless—sex can and often is funny, absurd, irrational), but as I mentioned before it also falls into the trap letting sexuality overly define her character. At one point, she forced under oath to list all the people she’s slept with as She-Hulk (too many to actually list in the comic, instead the panels transition to the court reporter reading back a scrolling list) as opposed to how many she has slept with in her normal human identity (around three). It is this kind of stuff that undermines Slott’s work to establish her character as a formidable lawyer—not because we don’t see her solving cases and doing research, all the things trial lawyers do, but because her sexualization is always at the forefront no matter what else she is doing.

Yet, despite this short-coming, Slott’s She-Hulk series tells some interesting stories and uses its self-awareness to explore some of the very troubling notions of sex and sexuality in Marvel comics that plague the title. Foremost among these is a story revolving around a sexual assault case against the former Avenger, Starfox (not to be confused with the anthropomorphic fox video game character).

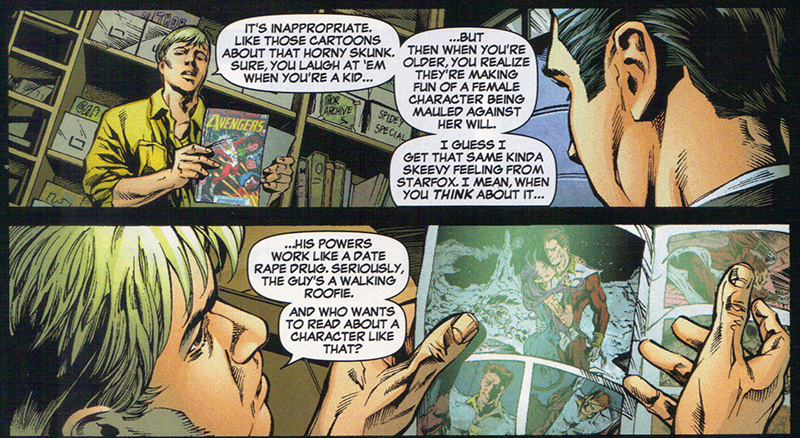

Even though Starfox was first introduced in the 1970s, he is definitely a character often associated with the 1980s. In addition to his super strength and vitality and his ability to fly, his main power makes him, in the words of Stu Cicero, “a walking roofie.” He has the power to calm people down, make them open to suggestion, “stimulate their pleasure centers” (whatever that means) and make them infatuated with him. Starfox is a character, at least in his hey-day as an Avenger, who was often played for a laugh. He was a libidinous lothario that the ladies drooled over and/or who constantly pursued them. However, the nature of his power puts his appeal into a questionable zone. What does it mean when your power influences people to want to sleep with you? How is that really different from a roofie or being a mind control rapist like the Purple Man? As a kid I never thought about it, but the adults who were writing the Avengers back in the mid-80s should have known better.

Slott clearly does know better and uses the plot arc of Starfox being accused of abusing his power to put this explanation into the mouth of Stu Cicero. Stu uses an example even folks not familiar with superhero comics should be able to understand: Pepe LePew—the horny skunk who is the Warner Bros. cartoon poster child for normalizing sexual assault through comedy.

Starfox’s dismissive attitudes to the allegation and his apparent lack of regret serves as a kind of stand-in for the stereotypical superhero comics reader, biding his time through “the boring parts” (women complaining about harassment and assault) and awaiting his eventual exoneration and/or escape to go on more salacious intergalactic adventures. The victim’s testimony, however, leads to She-Hulk realizing that her own past tryst with Starfox may have been influenced by his power. She tracks him down, and he gets his “exciting part”—a fight with She-Hulk wherein she kicks him in the nuts, but he is transported off-planet and out of reach by his influential and cosmically powered father (Mentor of the Titan Eternals – more ridiculous obscure continuity stuff). It seems that even in the comic book world the powerful and well-connected can escape the consequences of their actions. But beyond that, the story works to underscore how superhero comics have a history of not following up with the actual consequences of the puerile sexual behaviors and attitudes that have long permeated the genre. Later, it turns out that Starfox’s abuse of his power is a side effect of one of his evil brother Thanos’s schemes. In that way, he is left off the hook for the ultimate consequences of his sexual violence. He is allowed to remain “a hero” to be used by some future writer. However, at the same time as a result of seeing the possible abuse of his powers first hand, he has Moondragon (a character with her own history of abusing her powers for sexual dominance) use her psychic powers to turn them off, so he could never do it again intentionally or inadvertently.

For some people, that last bit of retconning is what is wrong with superhero comes, but I love that kind of stuff. There is a certain pleasure in reading a story that allows the actions of the past to stand, but recasts them in a way that takes into account a broader consciousness of the societal meaning of those actions. In this way, those old Avengers issues with a skeevy Starfox still exist, but now we know that skeeviness was not “heroic.” It allows the reader to correct his or her interpretation of the past, not by convincing us that how he acted in the past was acceptable (or just part of the time in which it was produced and thus excusable), but by reinforcing that it wasn’t. Sure, ideally I may have liked Starfox to have turned out to be the kind of douchebag that he seems to be without any caveats (I never liked the character), but at least now some writer who insists on using him has an excuse for his powers not working the same way anymore.

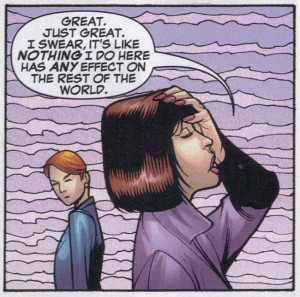

Of course, serialized superhero comics being what they are Starfox’s history remains in an ambiguous space. Everything that happens in these She-Hulk issues could be ignored by a future writer, and Slott seems to have written the series with the knowledge that he was toiling in a sort of bubble within the Marvel Universe. He puts words to that effect into Jennifer Walters’s mouth (and there is a new She-Hulk series starting in February, so we’ll see if that’s the case). But this willingness to grapple with comic book continuity (and an apparently frightening knowledge of it and its inconsistencies) is part of what makes the comic so compelling. Yes, on one level it appears to be more of the insular continuity obsessed dreck that weights down too many titles and definitely Marvel’s big “event” series, but rather than take it seriously, Slott brings the discrepancies and ethical slips to the fore as a way to invigorate his stories with pleasing ambiguity. The inclusion of material comics within the comic narratives lets those ambiguities exist as the seeds of possibility rather than mistakes to be fixed. Peter Parker profiting from his constant defrauding of Daily Bugle publisher, J. Jonah Jameson, the fact that half the beings in the universe were killed by Thanos (and later brought back), the existence of Duckworld, cosmic beings like the Living Tribunal, the contradictory fates of the Leader, and following up with undeveloped characters and stories that have their origins in crap like Jim Shooter’s Secret Wars—all of these things are explored in Slott’s She-Hulk series not with the pedantic obsession of the stereotypical comic nerd, but with good-natured humor and critical nostalgia.

Of course, serialized superhero comics being what they are Starfox’s history remains in an ambiguous space. Everything that happens in these She-Hulk issues could be ignored by a future writer, and Slott seems to have written the series with the knowledge that he was toiling in a sort of bubble within the Marvel Universe. He puts words to that effect into Jennifer Walters’s mouth (and there is a new She-Hulk series starting in February, so we’ll see if that’s the case). But this willingness to grapple with comic book continuity (and an apparently frightening knowledge of it and its inconsistencies) is part of what makes the comic so compelling. Yes, on one level it appears to be more of the insular continuity obsessed dreck that weights down too many titles and definitely Marvel’s big “event” series, but rather than take it seriously, Slott brings the discrepancies and ethical slips to the fore as a way to invigorate his stories with pleasing ambiguity. The inclusion of material comics within the comic narratives lets those ambiguities exist as the seeds of possibility rather than mistakes to be fixed. Peter Parker profiting from his constant defrauding of Daily Bugle publisher, J. Jonah Jameson, the fact that half the beings in the universe were killed by Thanos (and later brought back), the existence of Duckworld, cosmic beings like the Living Tribunal, the contradictory fates of the Leader, and following up with undeveloped characters and stories that have their origins in crap like Jim Shooter’s Secret Wars—all of these things are explored in Slott’s She-Hulk series not with the pedantic obsession of the stereotypical comic nerd, but with good-natured humor and critical nostalgia.

Another aspect of the series that works in its favor (and that has often worked in the favor of some of the best superhero titles) is its strong supporting cast—fellow lawyers Augustus “Pug” Pugliese and Mallory Book, “Awesome Andy” (formerly the Mad Thinker’s Awesome Android) as a general office worker, Two-Gun Kid (the time-displaced former Avenger cowboy) as a form of bounty-hunter/bailiff, Ditto the shape-shifting gopher, comic book-obsessed law library interns, and Southpaw, the angsty teenaged super-villain granddaughter of one of the firm’s partners all serve as interesting companions and foils to She-Hulk. In addition there is a whole range of guest appearances ranging from Hercules to Damage Control to The Leader to a then dead (and later returned) Hawkeye. She-Hulk seeks to embrace, rather than obfuscate, the over-the-top and often incoherent mess of the Marvel Universe.

It is impossible to put myself in a position of someone unfamiliar with the history of the Marvel Universe to know if She-Hulk is the kind of series you can enjoy without that deep knowledge, but I think you can even if you have just some knowledge—even just a passing familiarity with the tropes of the superhero genre would be sufficient (as it is sufficient for an appreciation of something like Alan Moore’s Top Ten). Like any other valuable work, from Shakespeare’s to Junot Diaz’s, knowledge of its many allusions and references improves and deepens comprehension, but is not wholly necessary. Ultimately, the crazy details, characters and events of past stories that Slott dredges up are so absurd and contradictory that for all we know as readers they could be made up on the spot.

Whatever the case, Dan Slott’s She-Hulk is the kind of series that is probably best for long-time fans of Marvel Comics, who still look back fondly on its stories and characters, but have grown up enough to admit their absurdity and their reflection of problematic attitudes. Yes, She-Hulk exists within the skein of the Marvel Universe, and thus may be an example of what Lauren Berlant would call “cruel optimism.” This is when ”the object/scene of desire is itself an obstacle to fulfilling the very wants that bring people to it”—the “scene of desire” in this case being an entertaining and adult superhero comic book immersed in its convoluted continuity—as what there is to work with often recapitulates the very problems the reworking is trying to overcome. And yes, there is not much creators can do within that skein to make lasting change to an editorial approach and historical context that reinforces the social attitudes that makes She-Hulk “a skank” while Tony Stark is a “playboy.” But Slott’s work does work to question those attitudes in an explicit and entertaining way, even if when it comes time to answer them (like in the panels above) suddenly Zzzax strikes again.

Great piece.

Osvaldo, you absolutely must dig up the handful of She-Hulks written by Steve Gerber. They’re an absolute scream.

Some of this does look fun and smart…but that thing where they read out all her sexual partners. Ugh. What the hell, comics?

Never gave it much thought, but aren’t all the X-Men telepaths guilty of similar stuff as Purple Man and Starfox? Charles Xavier, Jean Grey and Emma Frost have regularly forced their will on others. Can poor Scott Summers ever be sure of his feelings towards his mentor and girlfriends?

Pingback: Dan Slott’s She-Hulk: Derative Character as Meta-Comic | The Middle Spaces

I think in the x-books there’s at least some discussion of the ethics of mind control, isn’t there? Xavier’s supposed to be a good guy in part because he doesn’t do that…though I’m not remembering anything specific….

AB – glad you liked it. Slott is clearly a fan of Gerber b/c he uses a lot of his characters and creations in this run. I do plan to get those Gerber She-Hulk’s. I have all but two of his Howard the Duck’s, which I am waiting to find on the cheap before digging into those.

I have a another piece in the works (for a while now) about Slott’s Superior Spider-Man – while I don’t really like that series, it is interesting to see him attempt some of the same things from a different angle, but severely restricted by the fact that he is writing a Marvel flagship title (and thus why it fails a lot of the time – plus the art is meh). I think it is interesting to examine how the visibility and expectations of a title within a mainstream Big 2 company influences what it can do.

Charles, as Noah says – there has been at least discussion of that kind of stuff in the pages of X-Men, but while the ethics of actual mind control are clearly in abstract zone, mind control (or at least mind impairment) for the purposes of a sexual assault is within the realm of the actual world – I am not sure any of the X-Men have actually done that (and I could be wrong, I have not read a main X-title since 1988 – except for dip into Morrisson’s run and enjoying Whedon’s Astonishing, both in the early 2000s so there is a big gap in X-knowledge).

Yeah, there is a discussion, but it’s always condemned after the fact or justified by the need for superheroics, isn’t it? I read a few of the recent Bendis comics where the young Jean makes people do stuff that she wants and others just tell her not to. Plus, you have Prof X, the godlike Jimmy Stewart, peeking into the minds of almost everyone on the planet from a distance. I’m pretty sure Emma and her 3 stepford proteges have controlled others at various times. I don’t recall any of them ever being punished for forcing others to do stuff against their wills. Anyway, this has got to cause trust issues with Scott, just like it would with anyone dating Starfox.

And She-Hulk sounds like a fun book, but your essay probably satisfies my need to read it.

I really dug this essay as well. I mostly enjoyed this series and have taught the first volume once or twice. One of the more troubling aspects of the book’s treatment of gender and sexuality is that the overall plot of the first year or so is driven by how the men in Jennifer Walter’s life — John Jameson and especially the senior partner at the law firm — are presented as having the “right” perspective on what her relationship to her super-body should be, and the series is driven by her eventually coming around to understanding her body in the way that they do. I kept waiting for the series to critique that, but it never really did, as I recall.

I think the “Professor X is a supervillain” argument is sustainable. Jean Gray and Emma Frost actually *are* both supervillains to one extent or the other, though, aren’t they? Seems possible the prof gets a pass because he’s a guy.

BW, I think you are on to something there, but not sure it is as neat as all that. John Jameson wants her to not be She-Hulk and while Jennifer Walters may temporarily acquiesce to that (as we sometimes erroneously downplay aspects of ourselves for the sake of relationships), she never fully gives in and eventually rejects it.

But I do think you are right that the series does feature a lot of men making decisions directly and indirectly about her body (Reed Richards & Doc Samson, John Jameson, Holliway the senior partner, later Tony Stark) – but in every case she fights or resists that control.

They’ve dabbled with the idea of Xavier as a villain. Whedon did a bizarre story where he revealed the danger room was sentient and Xavier had intentionally enslaved it for the good of his x-men team so it could be used to train them. Ultimate Xavier as written by Mark Miller had no moral code against messing with peoples minds for what he saw as their own good.

Wow; that danger-room thing sounds Stan-Lee level stupid. Good for Whedon for keeping it old school, I guess.

I am not a Marvel fan, (though I know it better than many non-fans,) but I do admire the convoluted universe they’ve decided to maintain… I think it has got to be one of the most complicated narrative systems in human history. Compare it to the films, where every concept must be test-marketed within an inch of its life, and peter out once you’re past the origin point. It seems like it would be so easy for Marvel to scrap stories and characters, with no appeal to continuity, but instead they have to explain every adjustment, in often horrifically stupid ways. It’s like they’re keeping a promise…

Osvaldo, I also admire how you write your criticism with such playfulness and love for your subject, but still are able to criticize and analyze them. It seems like a very difficult balance for most.

Thanks, Kailyn. I take your estimation of my criticism as “playful” as a high compliment, because that is what it feels like to me – playing with a text. (It is probably for that reason that I love meta-aspects of comics so much).

For me, the act of being critical of something and loving something are inextricably bound together, as the former emerges from just paying close attention to the subject, and why pay close attention to something you can’t bring yourself to love to some degree or in some way. I probably would never take the time to analyze and write about something I find totally worthless.

Funny, I am never sure how my work will be received here because I am so concerned with superhero “junk” that seems like lots of folks here (and in other places) disdain. I brace myself for (and, to be honest, even hope for) a harsh response to those concerns. But even though I love lots of alternative comics (the first chapter of the dissertation I am working on is on Love & Rockets), I keep coming back to this “mainstream” stuff because the combination of its ubiquity and flaws just seem to make it so ripe for some critical attention.

There’s actually lots of superhero love on this site, I think, for better or worse.

re X-Men and the ethics of mind control — Mastermind/Jason Wyngarde’s treatment of Jean Grey is played basically as sexual assault, right?

Jones, I’m not exactly sure. It’s hard not to read that in there, but I don’t remember that it seemed like Claremont was particularly aware of it?

I agree with Kailyn–I haven’t read Marvel Comics since I was a teenager, but sometimes I like to click around Wikipedia, reading entries about the various cosmic/alien beings in the Marvel Universe. Apparently, the whole thing is even tied in with the “Cthulhu Mythos,” through Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard synchronizing their respective nerdy fantasy worlds and Marvel bringing Conan into theirs. I’m pretty sure that reading about this stuff entertains me a lot more than the actual comics would.

Jack I do that too, but it is only as fun to read as the Wikipedia contributor succeeds in making that convoluted shit comprehensible (they often fail). I would have had no idea what Starfox and his people were or about Moondragon’s history w/o looking it up.

Last year I gave Rick Remender’s Uncanny X-Men a try and it quickly became this thing with a future version of Red Skull with Xavier’s brain inhabiting some version of Onslaught’s body (or something), and Rogue and Scarlet Witch bickered about some shit that happened in some other comic, and some people called the Apocalypse Twins showed up and killed a Celestial, and destroyed S.W.O.R.D’s space station and it was clear the reader was supposed to know who all these people were and what it meant and be sufficiently impressed by the threat level and it took itself very very seriously . . . Those kinds of comics are the worst.

But then I think about how great All-Star Superman is and how it wouldn’t have been possible without a whole lot of really terrible Silver Age Superman stories.

I don’t really have a point with that except to say that I guess I have my limit, too – but it’s all just grist for the mill.

Noah — Claremont can be accused of a lot — an awful lot — of things, but naivete about sex is not one of them. As cf. all the BDSM stuff in X-Men over the years, or even more relevant, his reaction to a similar mind-control story in the Avengers, which he seemed to see as straight-up rape. (Sordid details here)

Jones, I didn’t say he was naive; the fetish stuff in that arc was clearly quite conscious. Still, he didn’t seem to do much or really be aware of the sexual abuse angle. Maybe I’m wrong, but that’s my memory of it. I could be convinced otherwise if someone who’s read it more recently wants to correct me.

Jones, I forgot about that story when I wrote this She-Hulk piece (though I did reference it in a post on Monica Rambeau (the other female Captain Marvel) I wrote for my site) or I may have included a reference to it. I bet there are several references to that kind of mind control rape stuff in Marvel comics.

I know an issue of Secret Wars II had the Beyonder have a whole harem of women under his control for a time – though I don’t remember which.

I was looking around the web at bit. Evidently, Morrison’s featured Jean mentally subjugating others. She at one point forces Emma to mentally relive a psychic sexual encounter with Scott (after finding out about their psychic affair). And then a future Jean realizes that he needs to fall into love with Emma, so completely restructures him to do just that (that’s rape by proxy, as this essay says). That seems right, but it’s been so long that I’d have to reread it.

And, yeah, Xavier is on another level of doing this kind of shit.

I suppose if I were Starfox’s lawyer, I’d say his power works like pheromones, which is a biological trait that he can’t control, so would you, the jury, prosecute the really handsome because their attractiveness makes things easier for them? More interesting than having it all play out as some sort of evil plot of Thanos’.

Except that the prosecutor provides evidence that Starfox can control it and willfully uses it or not (by bringing a Hydra henchman who he used it on to the stand).

Plus, that kind of argument is too much like the flipside of “she looked so good I couldn’t help myself” defense for rape.

Oh, I didn’t know he could turn it off.

These mind control rape stories are popular in fan fiction. I think Purple Man has appeared more in fan fiction than comics.

I’ve long felt that DC ad Marvel play insistently to their greatest weaknesses. The weaknesses being the attempts at seriousness and realism which highlight how unrealistic and unconvincing it all is; particularly in regards to continuity.

The massive shared universe seems extremely impressive when you are new to it but I think it’s a terrible idea to try and keep the continuity going with any semblance of reality.

The most valuable thing I got from reading the Batman Year One book was the extra from David Mazzuchelli where he had a panel of Bat-Mite and captioned it talking about the danger of adding too much realism to these type of stories, saying that the more realism you add to them the more unrealistic they appear. That really stuck with me, I was still a superhero reader at the time (I might pick up some Phil Winslade drawn superhero comics soon, but I havent bought much in years).

A lot of the newest stuff uses the seriousness of events as a selling point, but since this stuff can be ignored or rewritten so easily by later writers(and probably will be) and all the older stories that the events were built upon were treated the same way; so anything that ever happens doesnt carry much weight. But all the hype says “this is really big and serious and will have permanent consequences”.

I was a Spiderman reader for a very long time and it is amazing in retrospect how many really big traumatising life shattering events were sweeped under the carpet later as if they never happened. Some storylines even as they were going only seemed half real because it seemed like of the several writers writing Spiderman, only a few of them even acknowledged certain plots. There were so many times I wondered “did that thing really happen? Why isnt anyone talking about it? Did I miss something?”.

I remember there were times when writers came onto titles wanting to do their own storylines and got fed up with their own storylines being sucked into cross-title events. It seems like writing more popular characters comes packaged with this element now.

I would advise any creator against doing non creator owned comics but if they absoloutely had to do this stuff, I think the “elseworlds” approach of having your own alternate selfcontained version is the only way to get any dramatic consistency.

I’ve been looking at lots of old comic covers and examining them by the realistic standards the superhero comics generally try and attempt these days.

How about Kaine, the mad and depressed clone of Spiderman…

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kaine

…why did a vengeful clone make a meticulous costume like that with a space for his hair to flow out?

Super villains are generally more difficult to explain. Why would crooks dress up so fancy and hang out with other guys like that and often identify themselves as “bad guys”?

If you kept all the stories cartoony and silly, these questions wouldnt need to be asked.

http://ilxor.com/ILX/ThreadSelectedControllerServlet?boardid=57&threadid=98230#unread

….Superheroes who look like disco dancers.

Another thing about continuity: fans of minor characters often get upset how the minor characters have a completely different personality when the next writer gets a hold of them. Since writers arent familiar enough with the character or maybe even dont like them and dont care about changing them.

The thing is, there is no continuity – only the illusion of continuity – thus it is kind of ridiculous to get caught up on something that requires constant readjustment and that has sufficient gaps to allow for the generation of a limitless number of more narratives.

I have a kind of conflicted relationship to it, b/c I am tired as hell of continuity, and find slavish obsession with it rather adolescent – but still love stories that use the bizarre ruptures in continuity to go in different directions. I am particularly fond of Elseworld and What If? stories, in the same way that I love different takes on Shakespeare, alternate histories and reimaginings of classics. There may be a low signal to noise ratio in that stuff, but that’s true for a lot of things.

Oh, and speaking of Disco characters, I wrote about Dazzler here: http://soundstudiesblog.com/2012/12/31/blinded-by-the-sound-marvels-dazzler-light-sound-in-comics/

“And then a future Jean realizes that he needs to fall into love with Emma, so completely restructures him to do just that (that’s rape by proxy, as this essay says). That seems right, but it’s been so long that I’d have to reread it.”

I disagree that it’s rape by proxy. Emma asks Scott to join her and lead the X-men together. Scott refuses, because he’s lost hope in the world and just is apparently going to give up and live alone and no longer be involved in the X-men.

In the final scene of Morrison’s run., Jean exists beyond time in the divine Phoenix State, holding our sick universe in her hand. She is told to save the universe “”you have to water it, with your heart’s blood”

Time is altered, so Scott accepts Emma’s offer.

Calling that rape seems pretty off. I’d say the ending image is essentially about God’s grace (or some analogue) saving people and helping them find each other. Discussing it in non mystical or overly literal terms seems unhelpful.

(Besides, if Scott was under the influence of Sublime, which is implied, who is to say she didn’t remove the mind control rather than mind controlling him?)

There’s a scan of the sequence here:

http://4thletter.net/2009/03/my-scott-jean-knowing-when-to-let-go/

It is ridiculous to care about continuity in these comics and writers complain about it stifling their creativity…but the care about continuity is continually played up to make it seem like all these stories really matter, apparently a lot of Marvel and DC’s back catalogue sells on basis of it being important continuity and the way reprints are chosen and produced panders to continuity buffs.

Elseworlds stories (Dark Knight Returns, Kingdom Come) benefit from the separation and are sometimes very well recieved because they can maintain their own consistency and have a payoff that ongoing works dont; so I dont think there is any good reason not to switch to that mode.

As I said, these comics often play to their weaknesses. The stories are build up to make it seem like everything that happens is important. Can you blame a young fan for feeling unsatisfied if he is told these are grand masterful orchestrations then reads Peter Parker finding out he is a clone, hitting his wife in anger and panic, then joining up with his enemy in guilt(wtf?) and proceeds to kill innocents with his former enemy (or were they just knocked unconscious?), then he is persuaded to be good again, then later finds out he isnt a clone and all this trauma and murder is never talked about later?

There are several stories with Spiderman killing yet later writers often written that “Spiderman never kills”.

Not caring about continuity is a natural, sane reaction because they dont do it well and we know how unlikely it is to all work; we are left with low expectations. But we still expect all events to matter in Hellboy and Savage Dragon and Love And Rockets.

So why bother even keeping up the unconvincing illusion of continuity? Why not make every story arc an “elseworlds” story? I think the reason is that plenty of fans still buy into the idea of having all these stories mattering and making sense together; they want it all to make sense. These are the people who send death threats because everything that happens matters so much to them.

More than a decade ago I was utterly furious when I read that Marvel was considering ending their original universe and just doing new worlds. Now I think that is a good idea. But I’d rather people did a creator owned thing instead.

Early in the Claremont/Byrne/Austin run on X Men, there was a story where the mind-controlling Mesmero has brainwashed the X Men into thinking they’re carny employees.

Definite rapiness.

Jean is shown tarting herself up with excess lipstick, remarking that she has a “heavy date” with the “boss”…

Yeah, the implication is that Mesmero has been fucking her for days.

If memory serves, Claremont straightened that out in one of the “Vignettes” stories he did with John Bolton. Mesmero tried to use his powers to seduce Jean, but he wasn’t powerful enough to make her give in to that extent.

Actually, Mesmero has always been something of a wimp, hasn’t he?

AB, that is made even more implicit in the Classic X-Men addendum stories that came out with the reprint of that particular issue (by Claremont and Bolton.) It is pretty obvious that Mesmero is using Jean as his sex slave.

The issue of the Purple Man, mind control and sexual servitude also plays a very big part in the role of Jessica Jones in the Alias series by Bendis. The genesis of why she stops being a super-hero (“Jewel”) is because she encountered Purple Man and he mind controlled her over a long period of time as his sexual slave. Because of the trauma of the experience, she gives up super-heroing to become a private detective.

Jordan, Yep. That’s why I referenced him. He seemed like the most explicit example of mind control/sexual assault in Marvel Comics.

It is pretty obvious that Mesmero is using Jean as his sex slave.

No, he isn’t. I just looked at that story again. It’s in the second Vignettes collection. Mesmero tries to push her that far, but when he does, the Phoenix power asserts itself, and she starts to break his control. He finally relents, saying, “I give up. I can look… but as soon as I try to touch… the fireworks start. She’ll only stay hypnotized… if I leave her alone.”

Whatever the case, the desire to use her (and other women in the comics universe) that way echoes an adolescent (straight) male fantasy. Who is the imagined reader supposed to be identifying with there, the girl who avoids rape not through her own agency, or Mesmero the “wimp” who has his desires frustrated?

I see the Starfox story as addressing those creepy desires on the part of the reader from the point of an adult that knows (or should know) better.

I agree it’s super creepy, although Jean does avoid rape through her own agency. Mesmero is stopped by her subconscious fighting back.

I’m surprised Claremont was able to get the scene past Ann Nocenti, who was his editor at the time. She had a reputation for pulling the reins when he got too out there.

How can agency be subconcious, when it is defined by conscious choice?

I don’t think agency is defined by conscious choice. I think it’s defined by actions taken.

And in the case of Jean in that story, she does make a choice on some level not to submit to rape, even if that level is only instinct.

But you said “the Phoenix power asserts itself” – isn’t that power a form of possession? And if it, isn’t what happens to her body being determined by two forces outside of her will?

that should read “And if it is. . .”

Claremont didn’t see the Phoenix power that way. He did not view it as an entity that acted independently of Jean’s will. I know John Byrne wanted it portrayed as an independent entity, but he was never able to get that past Claremont when they were working together, and he couldn’t get it past Jim Shooter when he tried to do it afterwards.

I still want to do the Bloom County roundtable first, but maybe someday we should do a Claremont x-men roundtable, since folks seem so interested….

Hmm. I guess this discussion just reinforces the ridiculousness of arguing continuity since at different times things/characters have been portrayed as different ways.

But I have a question regardless: Wasn’t Shooter still EIC when they brought back Jean Grey for X-Factor? And, didn’t they portray her as being replaced by the Phoenix (I could be misremembering – FF 286, right?), so according to continuity, that wasn’t really Jean Grey being potentially made into a sex slave at all! :)

Gonna bust out that issue and read it – as it is the only Phoenix-related thing I still own.

I hate the X-Factor retcon. I think it was a betrayal of the readership. Claremont didn’t like it, either, and nearly quit over it. However, as I understand it, Phoenix-Jean is still Jean even after the ret-con. Jean’s identity–memories, personality, and so forth–were duplicated in a new body. The only difference identity-wise between the original Jean and Phoenix-Jean are Phoenix-Jean’s experiences after she’s introduced.

Speaking of meta-comics I found these panels in that issue: http://we-are-in-it.tumblr.com/post/67702706796/i-was-re-reading-fantastic-four-286-jan-1986

I don’t think Byrne is commenting on Marvel under Shooter with that. I think he was being deliberately absurd. Taken straight, that makes absolutely no sense. Shooter had a theory that “cosmic doesn’t sell”? Based on what, that huge commercial flop known as Secret Wars?

It was just a supposition based on Byrne not liking Shooter and it seeming to me like the kind of thing that he might have heard from on-high. In light of Secret Wars you may be right and I am wrong. Regardless, he is definitely making a meta-comment on comics, as the issue before this one is not a space adventure but that really terrible story about the kid who sets himself on fire to be like the Human Torch, so there is a sense of an “untold story” between issues.

Byrne did satirise Shooter (over a script by Ostrander and Wein) quite savagely in ‘Legends’, his 1985 DC series.

Pingback: Need To Know… 25.11.13 | no cape no mask

Pingback: Robert Mayer’s Superfolks: Grist For The Mill | The Middle Spaces

mea culpa…its been nearly thirty years since I read that story. Now that you bring up the Phoenix entity, it has jogged my memory and I stand corrected. The intent was there on Mesmero’s part definitely, and I imagine that is what most influenced my pre-adolescent reading of the text.

Yes, Shooter was still EIC at the time of the resurrection of Jean. I believe somewhere on his blog he states that he wishes he could take it all back. In my opinion it led to all the Phoenix cliches that are now a constant part of the X-men universe. Claremont pretty definitively showed that Madelyne was NOT Jean resurrected in issues 172-176…but once you bring the real Jean back you have left yourself open for all sorts of shoddy storytelling and plot back doors that I feel have caused no end to the meaningless deaths that now occur in comics. And Claremont himself was guilty of that by making Madelyne be Jean’s clone and all the horrific writing that happened during Inferno, only about three years later.

I enjoyed Dan Slott’s She-Hulk quite a bit, although it’s been years, so I don’t know how well it still holds up. I do really like Juan Bobillo’s art though. But one continuity-related aspect that hasn’t been mentioned is the “solution” that Slott came up with for explaining any continuity errors or incidents when somebody acts out of character. If I recall correctly, he revealed that people from alternate universes regularly “vacation” in the Marvel universe and impersonate characters, so every time something happened that didn’t make sense, it was one of those vacationers rather than the “real” version of the character. This is pretty silly, but I think it’s kind of hilarious, sort of implicitly saying that any writers of bad stories are interlopers who don’t really belong in the Marvel universe. That’s a weirdly protective take on the shared universe, seeming like Slott takes it all too seriously while still poking fun at the complexity of things. I find it kind of fascinating.

Yes. I didn’t mention it because I wanted to focus on the Starfox thing and this tidbit emerged as part of the recurring reference in the series to She-Hulk having slept with Juggernaut – which she denies. When in the court scene where her lovers are listed the lawyer challenges her with the Juggernaut accusation by showing the comic in which that scene is depicted (and thus, according to the conceit of the series, substantial evidence for use in a court of law).

I think rather than necessarily displaying an overly serious protective attitude to a shared universe, more importantly it is providing readers a mechanism by which to curate their own form of continuity (which is ultimately what many of us do even without that alternate versions excuse). It is providing and in-text ambiguity that the undermines all of continuity. Sure, Slott wants to use it to erase She-Hulk’s indiscretion with Cain Marko, but another reader (like me) could just as easily use it to erase Spider-Man’s clone saga or explain the return of Norman Osborne, or whatever.

That’s a good point. You definitely can’t accuse She-Hulk of being overly serious, so that’s not really a good description of what he’s doing. It’s a cute idea, like you said, allowing the “selective continuity” that readers practice to work as text.

If only there waqs any of this fun and self-awareness in Slott’s Spider-Man work.

waqs?

His Spider-Man/Human Torch limited series does have a lot of fun and playful continuity. So I’d check that out if you haven’t.

I recently checked out Peter David’s first 6 issues of She-Hulk after he took over for Slott. Ugh. Hackneyed and turgid. And he made sure to immediately undo the undoing of her sleeping with Juggernaut.

Was.

Thank you. I’ve heard of it being good but I’m skeptical given his current Spider-Man run mostly because I don’t think he has a good voice for the character.

Why did he do that anyway? I know Juggernaut was a good guy at the time but he still tried to kill Bruce and was her client. Jen may like sex a lot but she has standarts.

Pingback: Probably the longest set of reviews I’ve ever posted | The Ogre's Feathers