Is the War on Terror over yet? It was written to be a mini-series. After the 2003 fall of Baghdad, Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld outlined plans for an immediate invasion of Syria. Lebanon, Somalia, and Sudan were up afterwards, with Iran crowning the Bush Administration’s “seven countries in five years” plot.

It was a naive story, one modeled on World War II and the swift collapse of the Axis. A decade later, the American public can’t even stomach Syrian air strikes let alone a ground invasion. We would all like the War on Terror to be over, but it’s evolved instead. Now we’re stuck with a less combative but never-ending Cold War on Terror.

That could prove a problem for superheroes. Costumed crusaders make lousy diplomats. Captain America would just infiltrate those Syrian chemical depots. The Human Torch would take out Iran’s nuclear plants with a few fire balls. The Sub-Mariner wouldn’t negotiate with Russia; he’d fly in and grab Snowden by the throat.

It will take a few Hollywood mega-flops before superheroes change their big screen tactics, but I predict that change is coming too. Just look at the last time America’s legion of leotards faced a cooling of national attitudes.

1954 should have been a good year for superheroes. Sure, the plummet in post-war sales wiped most superpowers off newsstands, but the Man of Steel had made the leap to TV. The first two seasons of Adventures of Superman were looking like a hit for ABC. No wonder Atlas (formerly Timely, soon Marvel) Comics decided to revive their golden age sellers. Joe Simon and Jack Kirby’s Captain America cranked out a million copies a month during the war, with Sub-Mariner and the Human Torch right behind. Now the three were fronting their own magazines again. The Torch even returned atomic-powered, a happy side effect of the nuclear testing that awakened him from his desert grave.

Over at DC, superheroes hid on the home front during World War II. Except for a smiling, patriotic splash page selling bonds, you wouldn’t have known there was a war on. That’s part of why DC’s trinity—Superman, Batman, Wonder Wonder—were the only supers to survive the post-war plummet. They stayed out of Cold War politics too. The Man of Steel never came near the Iron Curtain. Instead of bashing Commies, Adventures of Superman softened Superman’s crooks into cartoonish comedy. DC stapled “the American way” to the old “truth and justice” credo, and that’s as far as the Red Scare crept into Superman’s true blue tights.

But at Atlas, superheroes remained bound to America’s real-world supervillains. So with Hilter, Mussolini and Hirohito vanquished to the Phantom Zone, they used the Cold War substitute. Sure, Joseph Stalin was dead, but Soviet sickles and hammers still replaced swastikas on Sub-Mariner’s first cover. Captain America stands with his shield raised in a self-congratulatory cheer below his new 1954 tag phrase “Commie Smasher!”

It made sense. Joseph McCarthy’s communist-vilifying absolutism was a good fit for unexaminedly violent supermen populating a patriotically distorted fantasy world of pure good and evil. The timing was right too. McCarthy’s popularity popped in 1950 with his never-substantiated charge that the State Department was infested with Communists. When Washington Post cartoonist Herbert Block coined the pejorative term “McCarthyism,” the Senator embraced it. His 1952 McCarthyism: The Fight For America even linked Communism to Hitler.

Atlas wasn’t the only comic book company backing McCarthy. Prize Comics hired Simon and Kirby to revive their brand of patriotic violence with another star-chested super soldier. Simon had titled his original Captain America sketch “Super American,” but he and Kirby went with Fighting American for their Cold War redo. Doing Captain America’s resurrection one better, Fighting American was literally a corpse, a dead World War II hero and right wing TV commentator reanimated and inhabited by his puny kid brother. And that’s the best definition of “MyCarthyism” you’ll even find.

So why didn’t any of these superpowered pinko-pounders last even a year? Captain America and the Human Torch went down in flames after just three issues. Sub-Mariner dribbled out ten. Stan Lee blamed the flop on the “stridently conservative scripting,” the same script McCarthy was working from. As a Senate chairman, he accused the U.S. Army of harboring masked Commies, and so the Army-McCarthy hearings kicked off in April 1954. On newsstands the same month, the first cover of Fighting American boasted: “Where there’s Danger! Mystery! Adventure! We find The NEW CHAMP OF SPLIT-SECOND ACTION!” The hearings ended in June, the cover date of the last issue of Human Torch. The last Captain America was removed from newsstands the following month. Which means Atlas made its cancellation decisions during the hearings. Commie-bashing superheroes fell with their Commie-bating role model.

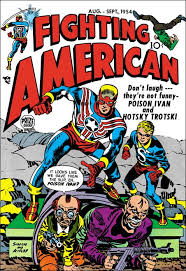

Instead of cancelling, Kirby and Simon went a different but equally anti-McCarthy direction. June-July is the last non-satirical issue of Fighting American. Prize introduced a redesigned logo for August-September, and the new cover includes two clownish communist villains and the ironic warning: “Don’t laugh—they’re not funny—POISON IVAN and HOTSKY TROTSKI.”

Jingoistic superheroism was literally a joke. The Senate condemned McCarthy in December, while Fighting American joked his way into Spring. Simon and Kirby had an eighth issue ready, but Prize never printed it. When McCarthy died in 1957, he stayed dead too. Captain America rose a decade later, but he was a changed man. Marvel even declared that 1954 guy an impostor. Stan Lee said he wanted to express his own “ambivalent feelings” through the new Captain and “show that nothing is really all black and white.” Or white and Red.

If history repeats itself, superheroes will be a joke again soon. But first our contemporary McCarthies and their “stridently conservative scripting” would have to flop. The GOP’s polls plummeted after the shutdown, but Senator Cruz and his Tea Party cohorts look fine in their gerrymandered districts. According to his filibuster transcript, Cruz even believes he’s a member of the Rebel Alliance fighting the Evil Empire in Star Wars. It’s not a comic book, but the two-dimensional thinking is the same. The Tea Party is happy as long as they have that pinko Obama to bash in the name of the American way.

I think for this argument to work you need to make a stronger case that the current spate of superhero popularity is a result of – or at least is related to – the current geo-political climate as influenced by U.S. foreign policy vis-a-vis “terror” – in the same way that we look back now and can see the first wave of superheroes emerging from the combination of economic conditions of the 1930s and then the war that followed.

While there are certainly arcs and events that take up many of the themes of “the war on terror” – Brother Eye and the surveillance state in DC’s Infinite Crisis, Bendis’s terrible Secret War mini-series, both Captain America and Spider-Man torturing or condoning torture of prisoners – not sure that comics themselves are popular enough for those to mean much, and not sure that the movies (save perhaps the Iron Man series, which admittedly are very popular) play on those themes and anxieties as much – maybe the new Captain America movie will.

The Dark Knight series is definitely all about the surveillance state and terrorism. So that’s the two most popular movie series, isn’t it?

Oh yeah. I always forget about the Batman movies – or try to – the Iron Man movies are just kind of goofy and overrated. I actively hate the Batman movies (for the most part).

I guess the argument can be made that post-9/11 was when all the superhero movies took off, thus. .. blah, blah, blah – I think that recent PBS doc tried to make that argument if I remember correctly.

I agree, Ovaldo. The key of the argument is whether current superheroes can be read in relation to the War on Terror in the same way that Golden Age heroes can be read in relation to 40s and early 50s politics. And I’d say it comes down to film since that’s the far larger superhero medium now. In addtion to Iron Man (as you pointed out) and Dark Knight (thanks, Noah), Avengers, SHIELD (TV but an extension of the film franchise), and Man of Steel also speak directly to the War on Terror. The overall surge in superhero movies is also a post-9/11 phenonemon. That, of course, doesn’t prove there’s a cause-and-effect relationship, but the parallel is at least suggestive.

I hate the Dark Knight films too. Not sure why they’re rated so highly. The first one (Batman Begins I think?) was just shockingly bad. The others were more run of the mill terrible.

“The overall surge in superhero movies is also a post-9/11 phenonemon.”

This is partly true of course, but there is a good argument that the crucial steps had already been taken. The CGI were there, the geek culture-mainstream culture convergence was happening (cf. The Lord of the Rings) and Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man had already been shot. While the Iron Man and Batman movies did play on the War on terror imagery and discourses, they are mostly absent from Spider-Man 2 and X-Men 2 for instance, which both confirmed the genre was economically viable.

I don’t know that it’s possible for manicheanism and might makes right in the face of evil themes to be absent from superhero films. That’s kind of the point. Global good vs. evil narratives are superhero narratives, in some not all that metaphorical sense. You don’t need to reference the war on terror for the war on terror to resonate with a superhero film.

I agree, Noah. The DNA of superheroes is WW2 absolutism. And that DNA will attach to any contemporary conflict and offer violent absolutism as its solution.

Hey, Chris,

First, you’d probably really love Dan Hassler-Forest’s Capitalist Superheroes: Caped Crusaders in the Neoliberal Age from 2011. It’s all about superhero movies post 9-11. It seems you’re two peas in a pod.

Second, you might also find my entry on Man of Steel of interest, since I take some issue with that book and reference something you wrote, but argue for a beneficial effect that terrorists have had on superhero (and other related) films, namely the villains have gotten more complex, serving as critiques of the heroes (compare the Burton Joker vs. the Nolan Joker). This isn’t because these movies aren’t grounded on conservatism, but, I suspect, it has something to do with their not being written by militant conservatives — most likely, the writers don’t consider themselves conservative at all. So I disagree that they’re “stridently conservative.” The heroic worldview is too deflated. (Conservatism can be self-critical, too.)

Many thanks, Charles. I’ll have to check out Hassler-Forest. As far as supervillains becoming more complex, I’d say Stan Lee invented the complex supervillain in 1961 and Moore took the trope to its completion with Ozymandias:

http://thepatronsaintofsuperheroes.wordpress.com/2013/07/15/the-thermodynamics-of-sympathetic-supervillainy/

“Pace critics such as Chris Gavaler and the aforementioned Hassler-Forest who have difficulty not making a 9/11 reference when discussing just about any contemporary action film, isn’t there always something of a perceptual analogy between any large scale cinematographic destruction set in a city and the one instance of destruction to a city we Americans experienced in reality (mostly through video on the TV)? Is the similarity on which the comparisons rest always ideological?”

Perhaps not intentionally. But doesn’t every representation inevitably express attitudes that are by definition ideological? Is there such a thing as an ideology-free depiction of anything?

“To answer Buchanan’s question if it’s possible to make a Hollywood blockbuster without evoking 9/11, I’m thinking probably not — not because everyone of these films is “really about” suppressing the causes of 9/11, or making it into a fantasy, but because the event has become our default source in the analogies we draw from these films.”

But the fact that 9/11 is an inevitable allusion, and even a default analogy, that doesn’t make it neutral or a-ideological. If anything, doesn’t ubiquity demand even greater attention and analysis?

It doesn’t make the reading neutral, but how about that Superman cartoon, “The Bulleteers,” is that now ideological, in post-9/11 terms? So, to get back to your first question, I don’t believe every representation is being ideologically controlled, which is the crucial point here. You can read anything ideologically, and maybe even make an interesting point about it, but to take that ideology as the for the art is dubious to me. It ultimately doesn’t allow for any counter-readings, because we’re all (readers, text and authors) just existing within its interpellating web. So, no, such analogies aren’t always ideological. I’d say that the total destruction of cities, such as in Independence Day, can play into a similar fear as subsequent acts of terrorism do, without the former being reduced to the ideological production of the latter.

“ideology as the *basis*”

I don’t think Chris is saying it’s reduced to being a product of the ideology. He’s saying that when you show a building or planet being blown up post 9/11, you’re accessing 9/11; it’s one prominent thing that comes up, for creators and viewers. You can’t really get away from that.

And I don’t see a reason to discard ideology as a useful lens of analysis. But using that lens exclusively or saying it’s the only useful lens is just as bad.

If y’all are saying that reading a post-9/11 destructive spectacle isn’t any more inherently related to a particular ideology based on the fallout of 9/11 as such spectacles predating 9/11, then we are all in agreement on this point. I think terrorism plays on many fears that have been with us a long time, not as a sui generis cause of them.

Just to clarify: sometimes mass destruction is just mass destruction.

I don’t think that it’s true that in a narrative any event is just an event. Narratives are always overdetermined and symbolic; you can’t get away from the symbolic if you’re telling a story.