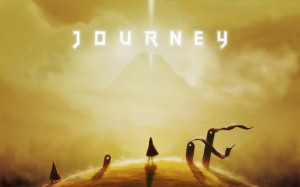

Journey is the latest game by Thatgamecompany and director Jenova Chen (best known for Flower). The story is very simple: you play an unnamed wanderer heading towards a mountain in the distance. While traversing deserts, caves, and mountains, you pass through the ruins of a once great civilization. Eventually, you uncover what happened to this civilization and reach your destination at the top of the mountain. There is no dialogue or text.

The simplicity is both a weakness and a strength. It’s a weakness in that the game – for all its beauty (more on that below) – is quite shallow. The game could be about faith, or science gone awry, or the inevitable rise and fall of civilizations, or an allegory for a single person’s journey through life, or it could be about none of these things. It’s a game that’s potentially about everything, which is the nice way of saying that it’s basically about nothing. Thematic muddiness is accompanied by minimal characterization or plot. But without a complicated plot or character relationships that demand attention, the game’s creators could focus all their attention on a wonderful visual and auditory experience.

If I had to describe the game in one word, it would be gorgeous. The sand shimmers in the sunlight as you surf down a dune. The pseudo-Arabic ruins cast ominous shadows. Giant stone centipedes “swim” through the sky while you try to avoid their gaze. And while you run, glide, or sand-surf through the levels, you’re always tempted to stop and admire the scenery.

The soundtrack, composed by Austin Wintory, is a worthy companion to the visual design. It combines cello solos with more complex, New-Agey compositions, and the music adjusts dynamically according to the player’s actions. But it always returns to the main cello theme that represents the playable character.

The level progression is strictly linear, though each level requires some exploration and puzzle-solving in order to unlock the next level. The playable character can glide to move quickly and access hard-to-reach areas, but only if the player has absorbed energy from floating bits of paper. The controls are basic and the puzzles are relatively easy, but planning out the best way to complete a level – maximizing your time in the air without wasting your finite energy – will provide an extra challenge for experienced gamers.

Another great feature of the game – something that I didn’t think about until after I finished it – was the near total lack of violence. I don’t expect violence in puzzle or rhythm games, but epic adventure games are a different matter. It’s been a long time since I played an adventure game that didn’t involve shooting, stabbing, or punching a virtual enemy. This game is even less violent than Super Mario Bros., as there are no evil mushrooms to stomp on. There are a few monsters in the game, but your goal is to avoid them, not fight them. The standard fight/kill/loot dynamic is absent, and instead the player is just left to explore, unlock the next step in the level, explore some more, etc. In practice, this means that much of the game has a relaxed pace that may annoy gamers who prefer a sense of urgency.

But as much as I enjoyed the game, that enjoyment was all too brief. A thorough playthrough will take three hours at the most (though if you speed through it, you can be done in only an hour and a half). I’ve read other reviewers who’ve defended the length, saying a longer game would be unnecessary and you can always replay if you want more. And others have pointed out that it only costs $15. I find neither of these arguments to be persuasive. Sure, I can replay the game whenever I want, but what I actually want is more stuff that I haven’t played before. I want more levels, more puzzles, more sand-surfing … basically, I’m a greedy, demanding gamer. And for $15 you can get plenty games that last a hell of a lot longer than 3 hours.

Another problem is the multiplayer feature. While the game is designed as a single-player experience, other gamers will join your game as they play through the same areas (assuming your Playstation is online). There’s no verbal communication of any kind, but in theory you bond with the other players by exploring and completing levels together. I say “in theory,” because in practice the multiplayer is ruined by that one factor which always ruins a multiplayer experience: other people. The random players who join your game are mostly interested in beating the game and getting their trophies, not in forming a bond with a complete stranger. So the multiplayer boils down to someone who joins your game and then wanders off to do their thing while you do yours.

But as much as I love griping, I can’t complain too much. I’ve beaten it twice now, and I enjoyed it both times. I just wish that the combined length of both times lasted longer than a single afternoon.

I only recently started playing video games again (a bit) after many many years of not playing (like… I had a Commodore 64 I played games on). This one sounds interesting, too bad it’s Playstation only. I wish there were more games with less combat/treasure and more exploration/characters. I tend to play on “easy” so I can breeze through the combat parts of rpgs and get back to the story parts.

So you have a PS (not a PS2 or PS3 [or, as of yesterday, a PS4])? I’m not a “gamer” per se, but I’m related to a couple, who might have ideas (e.g., the original “Metal Gear Solid”).

But I think there’s a split between your two desires — exploration and story. For most games, “getting back to the story” means getting back to the fighting, while the open-world exploring involves getting off-story.

Sorry, for the confusion. When I say Playstation I mean Playstation 3.

As for your point about exploration and story, I would sort of agree with you in practice, but not in principle. In practice, most story-driven games have a lot of violence, partly because that’s what consumers seem to like, partly because those are the types of stories that game developers want to make. In principle, there’s no reason why story and violence have to go together.

Hi Richard,

My last comment was actually to Derik, who seemed to be looking for game suggestion for a PS. Sorry to gum up your comments.

I, too, found JOURNEY to be a transfixing, wonderful experience. (I immediately played it again.)

But unlike you, I found that the multiplayer aspect — especially the first time around — was a central part of that experience. (I almost want to write *SPOILER ALERT*.)

When I first played the game, I had no idea that there even *was* a multiplayer component. I was wandering through the desert, without a clear direction or goal — when, eventually, I came across another character who looked like me. Cool, but standard for most games. I assumed it was an RPG — just another part of the programmed world.

But then it started acting and reacting in ways that were strange and unpredictable. When I would cheep, she would cheep; when I would spin, she (sometimes) would spin, or act in ways that seemed inviting but indecipherable.

Only after a while — albeit a short while — did I realize that this was another player. But even then, it was unclear: there was no way to talk to her to verify that hypothesis, save through that rudimentary series of cheeps.

Still, that one moment was, literally, uncanny. Something that shouldn’t have been alive suddenly *was* alive. Something that shouldn’t have had intention and purpose suddenly, possibly, *did*. I was talking — or trying to talk — with my computer game, and it was talking (or trying to talk) back. A Turing test in adventure game form.

This became, of course, part of the challenge. How do you interact with each other with such limited means. How do help another player to distinguishing between meaningful and meaningful acts and actions. Learning to communicates — to know each other — was part of the game.

And this is perhaps why, when I lost that first partner (and even the second, third, fourth partner), I felt a sense of absence or abandonment that I have never had before in these make-believe virtual worlds. (And why, when I would suddenly re-hear their distant cheap, I could feel my body react and lighten, as I frantically tried to reestablish contact.)

Clearly I am gushing. But JOURNEY was really that good. I only wish that other players could experience the game with as much of a black slate — as much of a sense of unexpected discovery — as I did.

Now I’m jealous. Your multiplayer experience sounds great.

For me, multiplayer seemed to be the central aspect of Journey. Many of the puzzles and environments are not only easier to navigate with a partner (both players can power each other’s flight through the use of the chirping function, for example), but actually seem designed with these partnerships in mind: the final stage, in particular, makes this clear as often the only way to keep power is for companions to huddle together (which has a less potent effect as chirping, but becomes necessary in this portion). More often than not, I found players who cooperated just for these reasons alone, which has an interesting effect on the narrative as well (especially during the parts of the final stage meant to be grueling). I even suspect the game’s short length was to allow for 2 players to complete an entire game together (though multiplayer will always run into the problem of wrangling people together).

One of these two, huddled together for warmth, is my daughter.

The Solo cup, I think, is not part of the original gaming environment.

“practice the multiplayer is ruined by that one factor which always ruins a multiplayer experience: other people” – you missed the WHOLE point. Same as Sattler, my friends sat me down to play it without spoiling the multiplayer factor, its a transfixing experience and Journey is a legitimate masterpiece because its philosophy is understood not by story, but by gaming experience. I’ve done the same with serveral students and, if unspoilered, they go trough the similar reactions. And it helps when talking about Jung and Campbell, even Kurosawa.

I have to echo the sentiment of the other commenters regarding the multiplayer. I did know about it (not all about it, but enough), and I found it wonderful. All my partners were uniformly helpful, and if anything, I thought I was holding them back. It was quite interesting what a little cheep could be (imagined) to communicate.

I also only managed to play the game in two sessions, and was pleasantly surprised when the credits rolled that every level I had a different partner, and what I had imagined was a continuous relationship with two players was many. The play on imagination and narrative here is really interesting.

All that said, the multiplayer was pretty central to the game–and again, I’m sorry your experience wasn’t as fun–and probably had something to do with its length. The journey is a hike, not a marathon or a sprint. Further, I will say that as someone who has played games a while, I’ve definitely thought the weird calculus of time/money/content. Considering how much repetition exists in games, whether grinding or simply set pieces, I appreciate more and more the games that aren’t bloated, are lean and not minimalist per se, but more muscular for it. If anything, it was the “monster” bits–because I wanted to simply explore–that I was disappointed (mildly) by in the game.