Glyn Dillon’s The Nao of Brown was released on the prestige-comic circuit last year to largely positive reviews. While most critics took issue with the work’s overly pat ending, the comic still made best-of-year lists and garnered breathless praise. Pitched as a capital-G Graphic Novel, the work aims for a sweet spot between a visceral, tear-jerking narrative and a thoughtful, complicated representation of a debilitating and misunderstood disease, with an art and writing style lousy with direct symbolism, careful repetition, and high drama. The work and its critical response function almost as a case study in the problems presented by these types of prestige narratives, especially in comic-book form, but in ways that can easily be mapped onto film, literature, and the other narrative arts. This is especially obvious when it comes to narratives about mental illness, which, with a few exceptions, are lacking or notably inadequate in mainstream and even independent media. Nonetheless, the critical response to these works, especially on the internet, tends toward a rapturous acknowledgement of the work’s affective dimension and its potential to raise awareness. The Nao of Brown is not the first or the worst offender, but it illuminates the problems with the prestige-narrative market, and the inability of those who suffer from mental illness to find just representation rather than well-intentioned but deeply misguided spectacularization. The Nao of Brown is a perfect example of this spectacularization, a work that, despite its best intentions, perpetuates deeply entrenched myths about mental illness and gender and uses its glossy surface to dissimulate a lack of faith in graphic narrative and a deep misunderstanding of what it means to have OCD.

Heartfelt Nao

Given all of this, the stakes are a lot higher than me explaining what Dillon gets wrong about OCD, and a lot higher than me hating this book. They extend to the possibilities of comics narrative, the problems of the current critical environment, and deeply entrenched myths about mental illness and gender. I think, most importantly, they extend to the responsibility that comes with writing about mental illness, given sufferers’ continued inability to find just representation in mainstream media, independent media and academic thought. I myself have struggled with primarily-obsessive OCD, and I had high hopes that this comic might correct some misconceptions about the disease, as Dillon says he intended. However, given the long history of misrepresentations of mental illness across all media, I felt frustrated, but not at all surprised, when the work didn’t measure up.

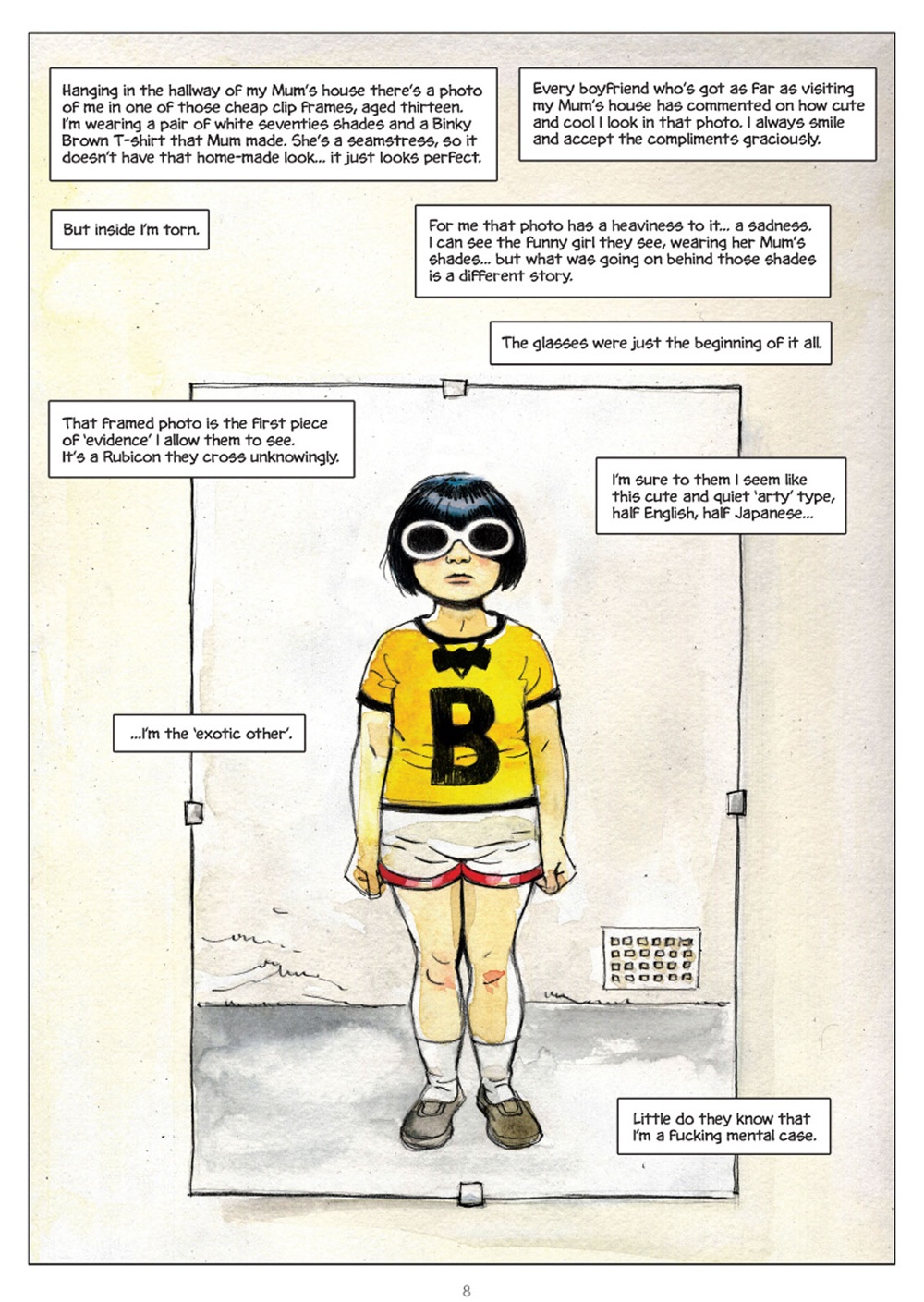

The Nao of Brown is the story of a young woman who is half-Japanese and half-British, lives in England, and works in a designer toy store for adults while being very, very cute. She also suffers from a very typical form of OCD in which she imagines committing violent acts in everyday scenarios, then is compelled to complete a series of mental rituals to banish the intrusive thought (this is known as primarily-obsessive OCD or sometimes less accurately called pure-obsessive OCD, I’ll call it PO OCD for the remainder of this article). The content of the intrusive thought and the corresponding compulsion varies widely from person to person, but Nao’s particular concerns are very common ones.

The book begins as a portrait of Nao’s day-to-day life, then chronicles her attempts to woo Gregory, a washing machine repairman who looks like her favorite anime character. He dispenses trite wisdom and generally acts like a terrible person. He’s also an alcoholic who has been sexually abused, because Glyn Dillon had a handwritten list of serious issues he wanted to work into his important story for adults. Their turbulent relationship is observed by Nao’s best friend Steve, who has, of course, been in love with her the whole time. The book reaches its climax when Nao and Gregory have a screaming match after Gregory criticizes Nao, and then he suffers a stroke. Nao is hit by a car in the immediate aftermath of the stroke, because that is also serious and important. In that moment she is able to perceive and accept the world, and we cut to a few years later. By then, Buddhist meditation has all but cured Nao of her debilitating OCD and she has become a mother (background details suggest that the child is Steve’s, but Dillon insists that it should be read as uncertain which of the two men is the father). Gregory writes a book about his experiences in which he gets to speak for himself in a way Nao is never permitted to. The End.

The Nao of Men

The whole book is interspersed with a fairy-tale sequence from Nao’s favorite anime, which would seem to add another level to the narrative but in fact comes across as entirely unrelated. The author suggests in a TCJ interview that it’s meant to be a merging of French and Japanese art as a sort of oblique way to talk about race. But the sci-fi fairy-tale itself is a conventional narrative with heavy-handed racial metaphors, and seems totally out of touch with the rest of the story, which barely touches on Nao’s Asian background.

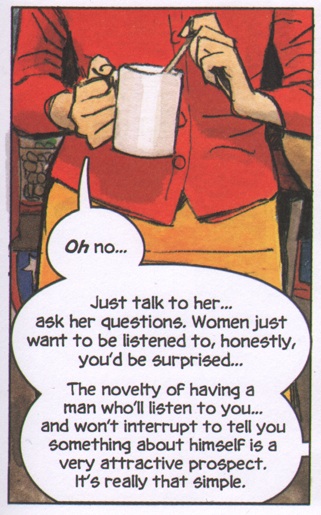

This sequence is indicative of a problem that cuts to the core of Dillon’s writing. Nao is more of a coat rack on which to hang various “interesting” problems and big issues than a real person. Any challenges that Nao does face regarding her racial identity or her mental illness are presented in a very cursory fashion, and the overall effect is a shallow one, as if Nao were simply a compendium of character traits ranging from a quirky outlook and a preference for Amélie-inspired fashion to a biracial identity and a serious case of PO OCD. Every part of Nao’s existence seems to be of equal weight; OCD is just another thing that makes Nao “unique” and “interesting,” not a debilitating condition that can make her life unlivable. Gregory suffers from this “coat rack “problem, too, although not in such an exaggerated way. Nao is a manic pixie dream girl, straightforwardly. Gregory Pope (get it?) is also a blank slate for serious issues like alcoholism and sexual abuse, yet these are afforded the status of real, fundamental pain, with a concrete cause (the absence of a father), and thus are considered more foundational to his being and given more legitimacy by the narrative. And then we have Steve Meek (get it????), whose personality is limited strictly to his ability to name a few bands from the 80s. As a fellow namer of 80s bands, I can say that doing so doesn’t really make you interesting, nor does it obligate people to sleep with you. But Steve, along with Gregory, is the narrative’s victim, and Nao is a source of male unhappiness, presented as too absorbed in herself to take note of others. This is one of many gross misunderstandings of the nature of OCD that dovetail with a sexist portrayal of rational men and hysterical women. This isn’t Nao’s story. It’s the story of the men surrounding her and it’s by and for men.

The way the narrative places the emphasis on men is subtle, but insistent. Nao’s wisp of a roommate barely brings anything to the narrative, while the two men, especially Gregory, do the heavy lifting. Nao is the star of the novel, but only inasmuch as she has the capacity to interact with Gregory and bear Steve’s child; breaking out of her own head by being available to men sexually and emotionally. The sexism and the irresponsibility of Dillon’s narrative aren’t Dillon’s invention, nor do they seem in any way intentional. The particular brands of sexism and misunderstanding that he employs are so pervasive in media (and conversation, and criticism), that his narrative is more symptomatic than unique in any way, and the problems with his perspective and his narrative style so deep-seated that they’re easy to miss. The permissive critical environment in which comics (especially the “serious” ones) exist allows them to fester and mutate far beyond the scope of the already hurtful story Nao tells.

Professional and casual reviews of the work have repeated and refashioned misconceptions about OCD endlessly since the release of the book, allowing either reddit-style “rational” dismissal or breathless reification (“this story about OCD will make you cry ACTUAL TEARS”) to set the tone. The reviews follow the book’s lead by demanding that women take responsibility for male sexuality and male problems, admonishing mental illness sufferers to “get over it,” and establishing a sharp contrast between “real” physical pain and “false” mental pain, which just so happen to be gendered male and female in the book, respectively. The most high-profile example is certainly Rob Clough’s review at TCJ, which does a fine job of examining the strengths and weaknesses of the book overall, but makes a series of very uncomfortable generalizations about OCD, self-absorption, and mental illness. Perhaps the most egregious is his statement on Nao’s inability to perceive the problems of others:

[Nao] assumed that everyone’s behavior and attitudes had something to do with her at all times, instead of realizing that everyone else had their own set of issues. She’s incapable of seeing that Steve is in love with her and always has been, believing that he thought of her as a sister. She’s unable to see that Gregory has deep-seated pain of his own that he’s dealing with by using alcohol. While she tries various techniques to work on her issues (including “homework” that involves writing down her bad thoughts), she’s too ashamed to actually discuss them. At the same time, she’s charmingly odd in other ways.

I can’t blame Clough for making these generalizations; he’s learned them from the book itself, just as he’s learned that “real physical pain” can erase the constant, self-perpetuating suffering of mental illness without the need for therapy. The fact that so many reviewers, not just Clough, latched onto this idea is a testament to the irresponsibility of Dillon’s much-lauded decision not to overexplain OCD.

The narrative also paints Nao as a hysterical woman, unable to take responsibility for herself or others. And because she’s a woman, it is assumed that she should be taking responsibility for others and be an understanding caretaker. The work ignores the ways in which societal narratives of what women or men should do can form the very foundation of OCD, either through a scrupulous adherence to the role, a debilitating self-loathing fueled by the inability to complete the role, or more often both. At the same time, the narrative punishes Nao for thinking about herself, for putting in headphones and “blocking out the world,” for very understandably not noticing Gregory’s invisible problems or his stroke, for thinking that Steve is not in love with her. In short, for failing to perceive reality and for failing to make herself happy. She is the cause of her own unhappiness, we are told over and over.

This might be a soothing pop-Buddhist trope for most people, but imagine how painful it is for someone whose deep torment already seems divorced from his or her personality, and who already feels, from the outset, that she should be able to get over it. The knowledge of one’s own irrationality and supposed ability to overcome are simply two more pieces of OCD’s complex, self-perpetuating machinery. Dillon occasionally hints at this when he says that Nao feels guilty about her inability to meditate or to hold Steve’s hand at a kite festival, but the narrative downplays the crippling nature of this guilt for an OCD sufferer and quickly moves on to blaming Nao for her “self-absorption” again. (If only she had listened to the old woman at the Buddhist center who told her not to wear headphones while riding her bike!)

The crucial foils for Nao’s “self-absorbed” tendencies are Steve Meek, her bland but caring friend, and Gregory, who seems to be in the position of Man Who Reads Books and Should be Taken Seriously despite the almost preposterously offensive way he behaves toward Nao and her condition. Nao is punished for her failure to perceive Gregory’s problems as he forces her into the role of nagging housewife, but his failure to understand her difficulties seems to be simply “understandable” and forgivable. Both of them suffer from invisible but debilitating problems. So why does the woman come off, to my eyes, as hysterical and self-absorbed, and the man as a sage, detached survivor of ‘real’ suffering? The narrative inches up to acknowledging that Gregory is not a good person, but quickly brings us back to his perspective, seeming to suggest that his arrogance and mean-spiritedness are both wise and forgivable. Of course, people who have suffered abuse and people who have mental illness can come across as cruel and standoffish to those who don’t know what they are going through. But in my mind, the narrative justifies Gregory as the one with “real problems” and dismisses Nao.

Nao’s irrationality also means, naturally, that she’s a powder keg just waiting for someone to scream at. In real life OCD is, by and large, a quiet and isolating disease that sufferers don’t want to talk about. I don’t want to generalize the experience of OCD, but an inability to discuss the disease and a deep sense of shame are very characteristic. Furthermore, because of the lack of media representations of OCD that go beyond superficial symptoms, many PO OCD sufferers are unlikely to know what they have, or even that their condition has a name and is shared by others. Far more common, sadly, is the sense that they are losing their minds and their self-control entirely, or that the intrusive thought is indicative of psychopathic tendencies. To assume that OCD will eventually reach a point in which it is unbearable and will be revealed in a noisy, massive fit of crying and screaming is a huge narrative mistake; OCD sufferers, in general, will do anything to avoid acting as Nao does toward Gregory when they get in a fight.

In essence, the book assumes that mental illness can be placed into the simple framework of beginning, middle, end; that something has to happen to break the cycle when all too frequently, nothing happens at all. At the end of the story Nao tells us her OCD is still with her, but this isn’t demonstrated in any way. Her intrusive thoughts appear at narratively convenient moments throughout the work anyway, but the ending, in which Nao’s OCD is literally knocked out of her, and she realizes that there is no good without evil (or whatever other self-helpy platitude Gregory cares to dispense), makes the work unconscionable in a whole new way. The narrative just isn’t up to the task of explaining how and why mental illness operates; it becomes increasingly clear that Nao’s OCD is just an easy characterization or a plot motor, not a real condition, and it feels shoehorned into the conventional narrative structure of the work.

The ending of the comic brings its victim-blaming tendencies out in full relief. Nao isn’t all better, she says, but she understands that she just needs to shift her perception and be in the moment. She realizes that she is the problem. As with so many other narratives about mental illness, chemical imbalance and physiological causes are an impossibility. It’s just a matter of training yourself. For some people, this is true, and it’s also true that many methods of cognitive behavioral therapy rely on Buddhist-inspired techniques like radical acceptance. But Nao’s affirmation that “getting hit by a car was the best thing that ever happened to me,” like Gregory’s explanation of the ecstasy of a stroke, not only comes off as callous in and of itself, but leads us to the statement that really clinches the work for me: “For the first time ever, I knew something that I had absolutely no doubt about. I knew right from that cold, clear moment that that truth would never change. I am my hell, it comes from me, it’s my responsibility and it’s all my fault. But that’s fine…My problems were not problems at all, but for how I related to them.”

If this understanding helps Nao or anyone like her or me, then that’s great. But to say that the problems of mental illness “are not problems at all” is unbelievably callous. I know what Dillon means when he says this. I know he wants it to be empowering. But when the unreality of mental illness is already an incredibly common discourse used to disempower sufferers, Dillon needs to do a lot more work to justify his use of this language. The narrative hasn’t earned its ability to make that phrase empowering, nor does Dillon himself seem to understand just how paralyzing the realization that “it comes from me” can be.

Narrative and Representation

This narrative failure extends more broadly to the problems of identity that the book wants to foreground. Understanding ourselves is, I think we can all agree, an open-ended process. However, with both Nao’s OCD and Pictor the tree-man’s self-assertion in the interspersed fable, Dillon posits a self that can be untangled from its surroundings and contradictions. Pictor the tree-man, a stand-in for biracial people like Nao, ends up burning off the tree part of himself and living happily ever after. He also chops down his family tree, because he lives in a very literal world. In this particular case, context doesn’t matter at all. The self is total and is pretty much extricable from everything that surrounds it (good to know; this will save me a lot of work in grad school). Context doesn’t matter; the pure self and the pure work of art are released into the world but always stand apart from it. While avoiding the trap that suggests that mental illness is a fundamental part of identity or integral to some kind of creative vision, this interpretation veers a little too far in the other direction. Mental illness isn’t exactly a tree that you can chop down, and neither is race. Dillon fails to acknowledge this, and he also fails to acknowledge the ways in which his own art might exist in the world once it’s been separated from his good intentions.

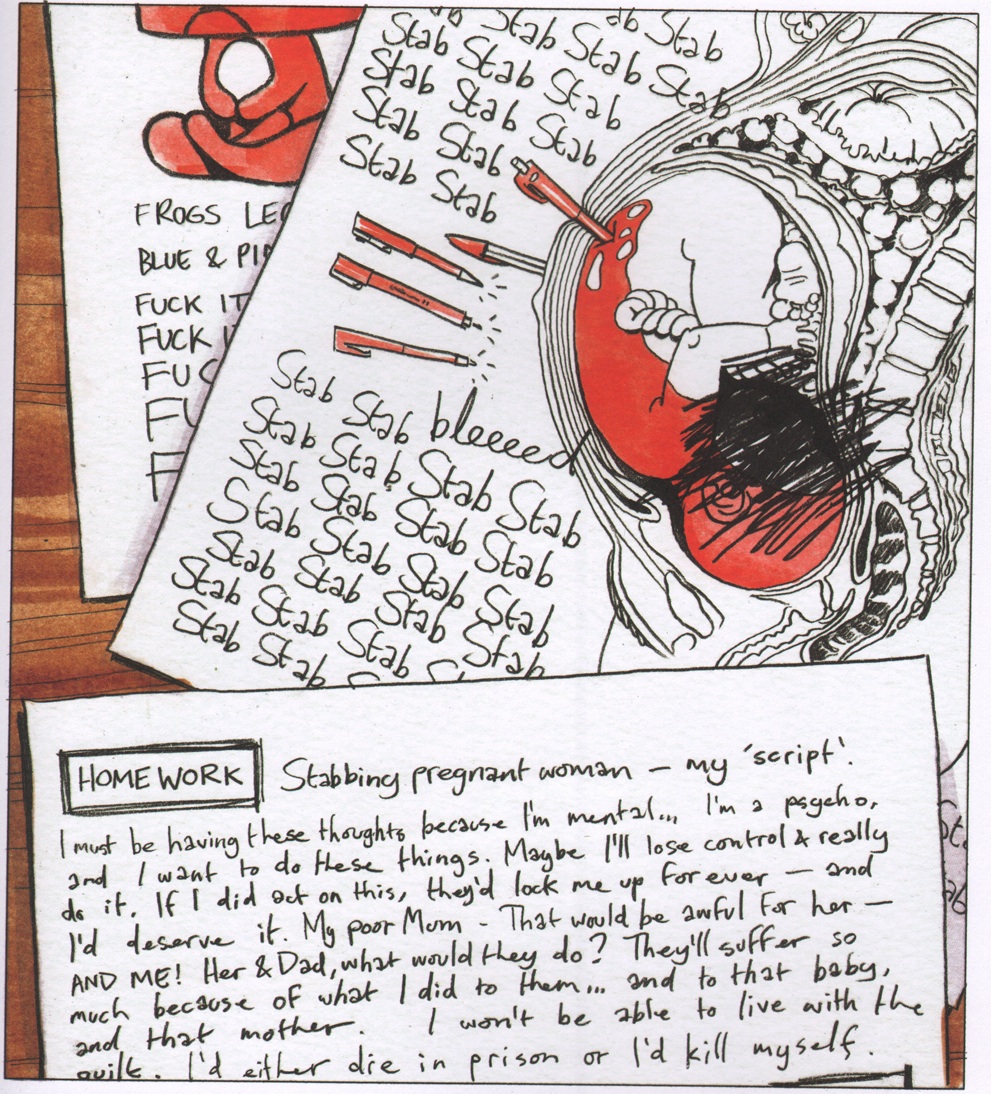

The inadequacy of the narrative extends to many of Dillon’s artistic decisions, especially as regards pacing. Nao’s intrusive thoughts are presented in such a slow, artful, and fabulously detailed manner that it’s as if she spent time on them, imagining them in lush and decadent ways. This is a fatal misunderstanding of what it means to be obsessive. At times the intrusive thought plays out in the mind visually. At others it is imagined only conceptually or textually. But in both cases, there is no artful slow-motion unfolding. It’s an immediate thought and an immediate response, an exercise in how little time you can give to something, (which of course is triggering and causes the cycle to repeat). The slow, dramatic unfolding of Nao’s thoughts gives the wrong impression, as if they were fantasies on which she dwelled, not intrusive thoughts that she has to drive away as quickly as possible — faster than the speed of thought, and if possible even before they occur.

The representation also reads as exploitative: look at how twisted and beautiful this is, says Dillon’s art. Look at how it blurs the line between imagination and reality, look at the dramatic tension, find yourself wondering if Nao’s really snapped this time because mentally ill people have to snap eventually. The misrepresentation at work here is so pronounced that it’s easy to think that Nao indulges these thoughts as fantasies—as I’ve seen them termed repeatedly in some reviews—or even as desires. The New York Times’ blurb review buys into Dillon’s representation in an amazingly offensive way, explaining that Nao has “spent her life suppressing her obsessive-compulsive violent fantasies, and engaging with geekier sorts of fantasies,” as if these processes were in any way comparable. This might seem like splitting hairs, but it’s essential to distinguish between intrusive thought and fantasy given their dramatically different paces, temporalities, and effects on the thinker, and given the very real consequences of assuming that people with OCD are violent or want to enact their intrusive thoughts.

The representation of Nao’s intrusive thoughts as fantasies, rather than fears, extends to moments in the narrative in which she is able to think about them lucidly and critically, applying Cognitive Behavioral and Jungian therapeutic techniques despite apparently not ever having been in therapy and ostensibly experiencing her OCD at its full intensity. Her “rating system,” which ranks her level of discomfort with an intrusive thought on a scale from 1 to 10 is indeed a Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) technique. However, someone who is not regularly in therapy would have great difficulty applying it with any kind of regularity; any distance from or critical perspective on the intrusive thought is impossible from the perspective of the sufferer without serious intervention. The kind of reflection needed to rank the thought on a scale from 1 to 10 will cause the obsessive thought to recur without massive changes to the thought process of the OCD sufferer.

Dillon draws Nao’s thoughts as occurring only once, after which time she is able to reflect on them, and he seems to think that OCD occurs only during spikes rather than being omnipresent. When Nao stays home all day at the end of work, waiting for Gregory to arrive, he comes closer to approximating what OCD is really like: paralyzing. If Dillon wanted to portray Nao as in treatment or even on medication, her intermittent spikes of OCD would make more sense, as would spikes brought on by stress in other areas of her life. If he’s intending to show the disease in full, as he claims to be, then his misunderstanding is beyond belief.

An integral part of Dillon’s narrative is built around Nao drawing out her intrusive thoughts after having them (described as “homework,” the idea for this de facto art therapy is attributed to her nurse roommate). This serves a dual purpose: it lets Dillon hint at some kind of therapy without actually broaching the subject, and it lets him get away with a visual meta-narrative, suggesting that his character acknowledges the twisted beauty of her violent fantasies just like he does. The idea of an OCD sufferer, especially one not under any kind of treatment, being able to draw out their intrusive thoughts in any way is simply unthinkable, and it highlights the depth of Dillon’s misunderstanding of how PO OCD manifests itself. Intrusive thoughts don’t go away after a single, intense episode. Any reminder, no matter how small, of a past thought will cause the sufferer to repeat the cycle. Consequently, any act that makes the thought more real, including writing, drawing, or even speaking about it, is avoided by the sufferer in almost all cases.

Binky Brown and the Nao of Brown

Despite the implausibility of an OCD sufferer drawing out her intrusive thoughts, Dillon’s attraction to visually depicting OCD makes sense. Comics are uniquely positioned to talk about PO OCD, I think, given their ability to move very freely between the mental and physical worlds and the fact that the intrusive thoughts and the accompanying rituals often take on hybrid visual, conceptual, and verbal components. Comics also have the distinction of being the medium of choice for the only two thorough pop-culture representations of PO OCD of which I am aware: The Nao of Brown and Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary (if you know of any others, please let me know; my research on this only led to depictions of other forms of OCD).

Binky Brown does a fairly good job of depicting PO OCD, and the struggles of its sufferers to identify their disease, in that it’s an agonizing book to read (and one that, I confess, I could not read in full). However, it’s also very limited by its cultural moment. It’s one of the founding documents of underground comix, so it’s natural that it should feel so underground, and to say that it’s limited by its moment doesn’t mean that I think it’s derivative, or that it’s lacking. Rather, I think it’s circumscribed by the kinky sensibility of underground comix, which always places the reader at a voyeuristic distance from Binky Brown (he acknowledges as much on the first page, even as he also calls out to others who share his condition to empathize). In many ways, this is preferable to the all-access pass that The Nao of Brown purports to offer the reader; it acknowledges the specificity of Binky’s condition and the difficulty of understanding. But in the wrong hands, it can come off as exploitative and stigmatizing. It’s also limited by a deeply psychoanalytic sensibility that attempts to trace Binky’s OCD to certain moments of his life, especially early encounters with the idea of sex. These follow very conventional narratives on insanity and neurosis, and it is common to recur to these kinds of narratives as a coping device. The sufferer often feels better about her condition if she can say “It all started when…” This means that Binky’s illness, like Nao’s, is presented through a beginning, middle, and end structure in which he finally overcomes the disease. In this case I’m more forgiving, rightly or not, because it is Justin Green’s perspective on a personal experience, and the process of constructing a narrative may be very healing for him. I prefer Binky Brown’s openly visible limitations to Nao’s feel-good universality, even if Green’s limitations are fairly serious in terms of the story they tell about OCD.

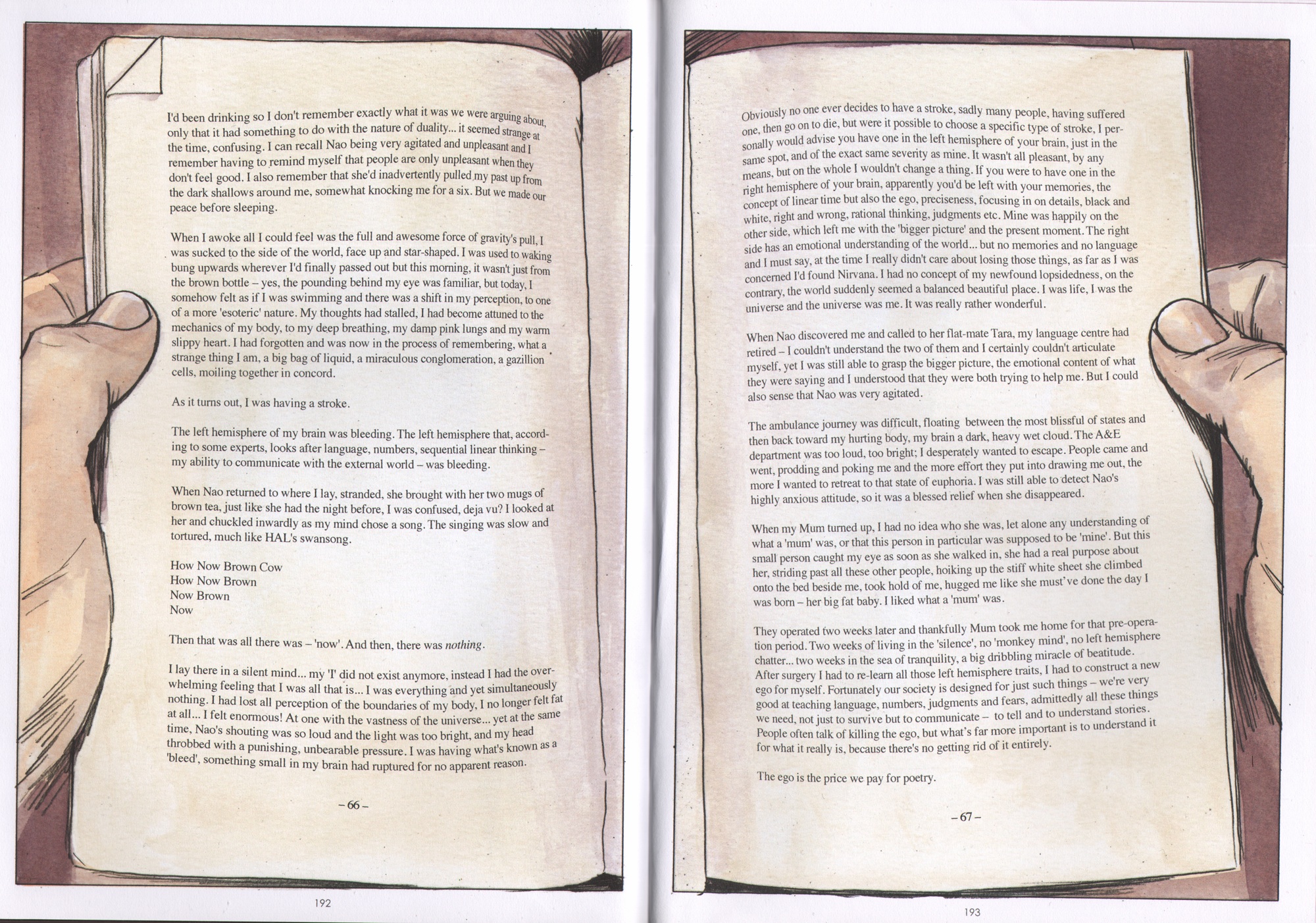

Nao attempts, and fails, to pick up on the tradition of comics about PO OCD by referencing Binky Brown on its first page. But it also backs down on the possibilities of comics storytelling by including an excerpt from Gregory’s infuriatingly-titled memoir, How Now Brown Cow. To me, this comes across as a lack of faith in comics. When really important things need to be said (by men), text steps in to pick up the slack, and the visual is relegated to a plain brown background and a little bit of shading on the pages of the book. In the end, the one who gets to speak for himself is Gregory, the “real” victim, in a rational, text-based way that gives little to no credence to Nao’s (heavily visual) experience. The text has already done some awkward heavy lifting—the book was written in the style of a screenplay—but here visual narrative is discarded for a full two pages.

This could be striking and interesting if it felt more like an artistic choice and not a compensatory move, a real lack of faith in what can and should be told by graphic narrative. It links Nao and the feminine to the visual and the unspeakable. On the next page, she has a vision of herself as a flower and is warned against becoming self-important as a result of the experience. Meanwhile, Gregory is somehow allowed to assert, via text, that he has been able to free himself from attachment, and also make such (profound!) statements as “the ego is the price we pay for poetry.” The extent of his engagement with Nao’s disease is his acknowledgement that she was being “very agitated and unpleasant,” and that this probably stemmed from some kind of unhappiness. The final word on Nao’s life also comes heavily filtered through Gregory via a long quote about Abraxas, apparently lifted from Jung. Nao and her son might get the last image, but Gregory gets the last word, and given the way the text has worked with word and image, Gregory’s verbal contribution is infinitely more serious and important than anything Nao herself can bring to the table.

Explanation and Feeling

I’m not asking for a perfect narrative, and there’s no ethical line in the sand that can be reasonably drawn when it comes to representing mental illness. But I do think it’s reasonable to ask for more than Nao gives us in terms of responsibility to both its audience and to sufferers of the disease it depicts. This is especially important because Nao, as the protagonist of one of only a few narratives about PO OCD, is inevitably going to stand in for PO OCD sufferers.

Dillon’s much-lauded decision to not “overexplain” Nao’s disorder would make sense in a world where PO OCD is widely known and understood. But in our world, where OCD is still synonymous with “neurotic,” “eccentric,” or “organized,” where it is often depicted as the key to personality and intelligence, and where it is frequently assumed that “we’re all a little bit OCD,” it’s irresponsible for Dillon to allow himself that luxury. To do so further propagates hurt, misunderstanding, and stigma, and it’s a shame because it’s a waste of both a good opportunity and excellent intentions. Dillon set out to write this work specifically due to a gap in media about PO OCD, and it is my sincere hope that people who read it and have been struggling with similar issues will find by reading the work that their condition has a name and is shared by many people.

That said, I hope that they won’t take the pop-psychology, the lack of any mention of professional help, and the victim-blaming at the core of The Nao of Brown to heart. Dillon doesn’t seem to have done his research on OCD or on the methods of treatment; he decides not to “overexplain,” but it’s hard not to feel that if pressed, he would be unable to explain the mechanisms of PO OCD and the pattern of intrusive thought and compulsion that characterizes it. In the aforementioned TCJ interview, Dillon explains that the narrative was initially about Gregory, because he was interested in the idea that washing machines might have some otherworldly connection. Once he decided that Nao, originally a minor love interest, would have OCD, he became more interested in telling her story as a reflection on quiet and unquiet minds.

This explains quite a lot. While he notes in an interview with OCD UK (unfortunately not available online) that he discussed the disease with his wife, who has struggled with it, and that he read several books and some online forums about OCD, he simply doesn’t understand what it’s like to have OCD. He also seems to have trouble differentiating the average person’s struggle with meditation and stress from the experience an OCD person might have. A host of other misunderstandings grow out of this initial one; reviewers like Seth Hahne of Good OK Bad pick up on the societal narrative that we’re all a little bit OCD, saying things like “it’s easy to see why few people realize that [Nao is] troubled any more than the next person on this sad, strange globe. In fact, she comes off at a glance better than a great number of us regular citizens,” or, “I think the questions that fuel Nao’s dreams and fears are the questions that haunt and help whole populations of this earth.” Dillon says that he wrote this work specifically for people with OCD and not for others. This is a well-meaning attitude that also happens to be dangerously arrogant; of course the book won’t only be read by OCD sufferers and of course it will be misinterpreted if you refuse to offer any tools for interpretation or understanding.

This feeds into a larger problem with the ways in which these kinds of SERIOUS narratives are received: in terms of affect, or in terms of increased awareness, both of which tend to foreclose real engagement and understanding. Both popular and professional criticism, especially in comics, tend to accord prestige to these types of narratives simply for going through the affective motions. “Low” internet culture calls this “feels,” and those with pretensions to “high” internet culture, like Seth Hahne, call it “a delicate admixture of sobriety and humour,” but the end result is the same, and both are entirely inadequate to address the narrative and the nature of real-life mental illness.

Affect is an important part of reading, and the ways in which we respond to works are valid. However, that doesn’t mean that criticism should just involve telling everyone how much something made you feel. Feeling is a complement to, not a substitute for, critical thought. Even the reviews I read that had literary pretensions, comparing Nao to the great(ish) works of contemporary lit, fell back on this affective dimension to explain why the narrative was IMPORTANT and INTERESTING (and not too depressing!), rather than on any kind of critical analysis. When we as critics participate in this kind of conversation, or when we share that Upworthy post (You Won’t Believe What This Woman Has To Say About Depression)! we’re positioning ourselves as people who observe mental illness for our amusement/catharsis.

It’s a tricky situation, because there is a sense in which just raising awareness can be helpful; Nao and that one episode of Girls, whatever their other merits, do seem to have gotten people talking about OCD. However, awareness is only a tentative preliminary step on the path to real engagement with other people. The rise of the awareness-industrial complex has foreclosed the possibility of understanding even further. Awareness is important, but it’s hardly sufficient. When you’re talking about an illness like OCD, which just about everyone is aware of but few people understand, the problems of awareness come into sharp relief.

This is a second problem for all readers: and it’s a tough one. Where do we draw the line in telling authors and corporations that the minimal acknowledgement of our existence isn’t enough, and that it’s not necessarily good? While the arrival of the first [insert identity category] character in any mainstream media often sets of a wave of interesting discussions about identity and representation, the post that goes viral is almost always a wildly enthusiastic response, no matter how stereotyped, tokenistic, or coy the representation in question. While there is value in seeing someone who looks like you or thinks like you or desires like you on the big screen or in a major book, I no longer want to give anyone the message that any representation, no matter how mistaken, is acceptable. I will no longer tell anyone, from small-time authors to major corporations, that they can not only get away with tokenism, but that they will be greatly rewarded for it. I no longer want to give anyone points for recognizing that various groups of people exist, and if that recognition involves speaking for me, I’m even less interested.

Some people with OCD have responded enthusiastically to The Nao of Brown, and I am not, in any way, here to take that away from them. I am glad that the experience was a positive one for them. However, we as critics and readers need to stop assuming that the bare fact of representation and minimal awareness is always a positive one. Just as affect isn’t sufficient for a critical and understanding engagement with another person, awareness isn’t enough. And we need to think long and hard about where these messages of awareness are coming from, and to whom they are addressed. I’m glad to see PO OCD getting more attention. But I would like to see it getting the kind of attention Fletcher Wortmann, Mara Wilson or Olivia Loving have been giving it, or in the world of graphic narrative, the kind of attention that Epileptic gave to mental and physical illness. (Seth Hahne compares Nao favorably to Epileptic because it’s not so “mopey,” wrapping it up with an always-timely lighthearted reference to suicide. To his credit, he also invites ”heated discussion” about the work, so, here I am!) To really talk about mental illness, we need to invent new ways to talk about it that don’t follow the same old narratives, if Nao can send us down that path, all the better. But we’re not there yet.

Nao’s intentions are positive, and I want to give Glyn Dillon credit for addressing the issue of PO OCD. It has the potential to do some good, and for many OCD sufferers, it already has. By the same token, I do not think that his intents were sexist or otherwise discriminatory. I am aware that he is telling the story of one person’s OCD, and not mine or anyone else’s. But that doesn’t address the fundamental problem: the narrative is feeding off of a larger context of sexism and the stigmatization of mental illness, and it’s reinforcing them because it steadfastly refuses to explain the condition or challenge many deep-seated notions about mental health. Out of context, perhaps in a parallel universe, Nao isn’t so bad. But in a world where seeking out mental health care is likely to get you told that you’re either crazy or one of the conformist sheeple masses, Nao becomes untenable really quickly. I know what Dillon means when he says that Nao’s problems “are not real problems.” I know that his intentions are good. But when he says those words, they’re riding on the wave of thousands of stigmatizing, generalizing, hurtful statements that have been made about mental illness’ unreality. And when he makes a work like Nao, he is feeding into a long tradition of prestigious narratives about serious issues the make a visual and emotional spectacle of their subjects and promote awareness, but never engagement.

Thanks to Jacob Canfield and Noah Berlatsky for helping me complete this article and for being very patient with the long process of writing it.

___

Update: Quotes around one phrase were removed so it was clear they were not meant to be attributed to Seth Hahne (see comments below for fuller discussion.)

Hey Emily. Lots to think about here, but I thought I’d just say briefly that the issue of tokenism and representation seems especially important and worth thinking about in light of recent discussions of the lack of diversity (esp. women, but other sorts of diversity as well) among comics critics. It seems like the problems with exotification and basic ignorance you’re talking about are likely to be exacerbated in a situation where critics are homogeneous in terms of gender, etc.

Absolutely! I think this is true in all of the narrative arts, but especially in comics. What’s interesting to me is the way in which even the open space of the Internet seems to limit criticism; even apparently diverse groups often end up hitting the same notes in terms of affect and awareness.When the group is as homogeneous as a lot of critics’ circles, especially in comics, the problem gets even worse. That’s why I visit and why I’m really really excited to be contributing.

On another note, I just realized that Nao won Best Book at the British Comic Awards last night.

Interesting thoughts. I appreciate most (and think you’re probably at your strongest) when you speak to the matter of OCD and its depiction. I can’t really comment on the validity of your descriptions because, as much of our culture, I know little of the condition. (In fact, it wasn’t until well after I read The Nao of Brown that I realized Nao’s condition was OCD, which is why my review makes no mention at all of OCD.)

On a lot of your other points, there’s simply too little intersection with our interpretations of the characters for me to really interact. Even in your descriptions of Nao, Gregory, and Steve, I found myself wondering at how we two could be interpreting the very same characters so variously. I saw Nao as a positive character hounded by an unnamed Something beyond her control, I saw Gregory as a likeable villain (also driven by things beyond his immediate control), and I saw Steve also as a negative character, friendly on the exterior but nursing deep wells of antagonism and resentment. Of the three, Gregory’s issues have the most external evidence, but none of the three really see each other’s problems with anything approaching clarity. Of all the characters, Nao stuck me as the least self-centered.

I didn’t so much appreciate what I felt was your shoe-horning of Nao into the MPDG trope. I’ve never been super comfortable with the designation, for one, but I think you’ve mistakenly read her as being aloof to those around her. Case in point, the text seems fairly clear that she is very much not oblivious to Steve’s infatuation with her. She’s known for years but hides that knowledge because she doesn’t feel prepared to deal with it and whatever it would mean for her life.

____

On a personal note, I thought it was a bit unfortunate that “we’re all a little bit OCD” arrives in air-quotes in such a way as to appear to be a direct quote from me, since I never actually said that (and likely wouldn’t). I also think tying my particular quotes that you used there is probably a misstep and not as indicative as you represent, but that’s less concerning to me than the appearance of misattribution.

Also, as someone whose grandest academic feat is a barely-earned highschool diploma, my pretensions are strictly middlebrow—if they’re even pretensions at all.

Also, you’re right and I think the toaster/bathtub reference was probably singularly unfortunate. So thanks for the reminder to be a better human :)

Hi Seth-

We’ve already talked about this a little on Twitter, but thanks very much for reading and commenting, and for your friendly disagreement! I think we do see the characters very differently, and there’s probably no getting around that; I saw many other people saying on the Internet that Nao herself was self-absorbed, but you certainly don’t say that, and I also disagree with this interpretation. However, the TCJ review and several others, as well as the book itself, suggest this reading, in my opinion (especially by emphasizing Gregory’s narrative near the end of the work).

I see what you mean about the quotes, and while I tried to be careful about differentiating a larger societal narrative from what you actually say in the review, it does come across as putting words in your mouth, which is a mistake. It seems that with those two quotes you might be speaking more to the imperceptibility of Nao’s problems and the fact that fears about good and evil are somewhat universal, but the phrasing made me a bit uncomfortable. Still, I see your point; it’s not the strongest link and I’m sorry if it made you uncomfortable!

As for the MPDG trope, it’s true that it’s become a critical cliché at this point, but I think it’s quite applicable to the way Nao is represented in the narrative. I don’t think being an MPDG means that Nao has to be oblivious; for me, it’s more in the way that she is drawn and the way that she relates to men in often quirky ways. The kite festival page definitely shows that Nao is aware of Steve’s affection, but the narrative seems to condemn her thoughtlessness toward Steve at times, as when he gives her the boots.

Gregory and Steve are not sympathetic, per se, but I think they’re the ones whose perspectives we tend to see. This really just comes down to two very different and valid readings of the work and there’s not much getting around it.

Having academic pretensions is definitely not a pejorative thing (if anyone can be accused of pretentiousness, it’s me)! If you have academic pretensions, keep them by all means! If you don’t, that’s ok too. Your phrasing stands out from a lot of internet criticism, which is why I used it as an example of a different take on the genre.

For anyone reading this article, I recommend reading Seth’s whole review here: http://goodokbad.com/index.php/reviews/nao_of_brown_review. It’s much shorter than mine and makes a great companion piece to my work. Also, you can avoid any accidental misrepresentations on my part this way!

Also, Seth, it’s really interesting that you didn’t know the narrative was meant to be about OCD. For me that’s one of it’s biggest problems. It doesn’t need to broadcast what OCD is all about necessarily, but I do think Dillon should have been a little clearer since so many people are not familiar with it. A lot of the issues I have with the criticism of the work come from Dillon’s unwillingness to explain. It’s a valid and interesting artistic choice, but I’m not sure it’s a responsible one.

*one of its biggest problems. So much for my academic pretensions.

Interesting article and it gave me much to think about it. If you have a blog or other place where your writings appear, please drop in a link.

I’m hoping Emily will blog more here!

Seth, we removed those air quotes for clarity.

Thanks to both of you! My current plan is to blog more here sometime, although any future pieces will be shorter and less agonizing to write. I’ve always been very nervous about blogging, especially the immediacy of it, but writing this piece has made me want to do it again. It was really nice to be able to take my time with this piece, and really nice of you, Noah, to be so patient!

Emily – One of my worries about the popularity and proliferation of MPDG is that it seems (to me) to lean a bit too much into the kind of sexism that critics are hoping to use the trope to combat. I might be very wrong on this point, but the MPDG seems to describe bivalently a type of person that exists across sex/gender boundaries—and describe a kind of person who actually exists. I know, personally, quite a few (more than ten, perhaps more than twenty) people of either sex who fulfill pretty solidly the terms of the MPDG (save for that, as real people, they aren’t a part of a discernable narrative). And to my eye, the Doctor is the fictional character who best fulfills the trope is a male (for now). That we make the final defining attribute of the MPDG be the sex/gender marker worries me. I don’t know if I’m properly explaining myself here. These are still nascent thoughts.

RE Thoughtlessness, I agree with you that the narrative condemns particular episodes of Nao’s thoughtlessness (or the appearance of thoughtlessness). If Nao had a laughtrack, there would be a big audience “Awwwwww!” when Steve is left behind with the unseen frog card. At the same time, the narrative is not exactly kind to Steve, giving off strong creeper vibes in many of his scenes (especially when the camera lingers on him after Nao departs a scene). The impression I got was that these were messed up characters in a messed up situation in a messed up life. None of them were heroes (except maybe Tara, who is never not kind and whose only fault is leaving snacks out for mice).

I’d also agree that we see a lot of Gregory’s perspective (for a book about Nao). But the narrative doesn’t treat Gregory’s “wisdom” as being all that great (’til perhaps the finale when he’s been traumatically removed from anything that ever was Gregory). Nao almost immediately eviscerates his unearned locquaciousness and for the remainder of the book, his quotes from Hesse and Jung and elsewhere are suspect—bits of wisdom, perhaps, but wisdom from the ass at best.

I think Steve gets much less perspective time than either Gregory or Nao. He always felt the most hollowly developed to me (which is fine because it’s not his story). So far as I believed, his place in the story was to give the reader a sense of how Nao would be perceived by the people in her life who merely knew her as quirky but were ultimately excluded from the privilege of knowledge of her condition. Steve, I felt, was to be the reader’s entrypoint.

I can see where you’re coming from with concerns RE Dillon not making the presence of OCD explicit. I can only really speak to my personal experience as someone who knew very little about the condition. I read the book and recognized that Nao had something serious and debilitating affecting her life, something that was preventing her from living life as I might but also something that was enough held within her that those around her might merely chalk it up to eccentricity (as friends would chalk up my own foibles). After I read the book and wrote up most of my review, I looked at other reviews just to see if I had missed anything major, and many made reference to OCD. That led me to look more into it (because obviously Nao is a departure from what we see in things like Matchstick Men. I have long been aware that pop cultural exhibitions of mental conditions is often innacurate, mythologizing bits and pieces of schizophrenia, Tourette’s, etc. so I didn’t presume that Nao was necessarily accurate. What it did do was introduce me to the idea that whatever I might have thought OCD was, there were varieties of the condition. That was rather helpful for me in that if I ever am made aware that someone I know suffers the condition, I won’t be tempted to make assumptions about its nature. So for me, personally, I didn’t feel Dillon’s treatment did a disservice—though I can see the potential for danger.

Noah – Thanks for that. It was a small thing, but I appreciate it.

I think the main difference between how you’re reading the book and how I did is, like Nao’s opinion of herself, you seem to want to read the characters as either good or bad, that one of them has to “win”. I don’t see Gregory as acting like a terrible person or being an alcoholic, and I don’t see Nao as being thoughtless or self-absorbed – I see her and Gregory as two people with problems who don’t understand each other, don’t realise that the other has problems because they’re both trying to hide them. It’s that, rather than Gregory criticising Nao, that’s what causes their argument. Nao also doesn’t see Steve’s feelings for her because he’s hiding them. We, the readers, only know how he feels about her because we see him when she’s not there.

The end may seem trite to some, but I don’t agree. Four years after Gregory’s stroke and Nao’s accident, Gregory’s published a book and Nao’s had a child and seems to have her shit together. That doesn’t seem an outrageous timescale, not to cure her condition but to learn better strategies to manage it, which allows her to do things, like becoming a mother, that she was previously terrified of. My own experience is with chronic depression, not OCD. I lived with it for many years before it came to a head in a crisis of sorts. Over a period of about six months, with the help of a sympathetic counsellor, I worked out coping strategies that still stand me in good stead ten years later. The condition is still there, but I can manage it much better than before, and I now have a fuller and happier life than I would have dared previously. Perhaps the book could have shown more of how Nao worked out her own strategies, but the end actually rings reasonably true to me.

Incidentally, while you assume the child is Steve’s, I thought he was probably Dave’s. Again, four years is more than long enough for everyone to have moved on.

Wait a minute. Does the book never openly identify Nao’s condition as OCD? If you’re trying to raise awareness of something, don’t you need to start by saying its name? That’s not essential to art but it is essential to activism.

I haven’t read the book, so this may be an unfair judgment, but the place where I trip and fall down and don’t get up again is: “I am my hell, it comes from me, it’s my responsibility and it’s all my fault.”

The first three items in that list are things everyone with OCD already knows; that’s the nature of the condition. The last item is–if you’re talking directly to people with OCD, which Dillon seems to want to–a truly devastating thing to say. It seems to come from ignorance rather than malice, but that level of ignorance is tough to pardon.

We call it mental illness for a reason. It’s not her fault. She’s fucking sick.

The only place the book actually mentions OCD is in the blurb on the front inside flap of the dust jacket, but it does mention it.

Katherine – I think you can only approach those lines within the context of the book itself. Both Gregory and Nao arrive at different solutions to their problems and, this is a bit spoilery, but Nao’s solution isn’t shown to be an end. It’s a temporary moment of semi-peace bought by playing an emotional trick on herself. She may find a longterm solution in it and she may not. The ending is ominous. Also, OCD is not Nao’s only problem so it’s possible that the Buddhism/gnosticism-lite she uses to calm herself is helping out with the non-OCD issues, relieving some of the stress that cause her anxiety moments.

Patrick – The identity of the child’s father is a bit vague, but presence of the accordion while they’re fingerpainting suggests rather strongly that Nao is co-habiting with Steve.

Hi Seth-

What you’re saying about the MPDG is interesting. I think what it comes down to for me, and I didn’t really think about this until you prompted me to, so thanks, is the way the narrative makes use of the character. The MPDG is the MPDG because the narrative uses her in service of men’s desires and self-realization; this comes out of a long tradition of the way women have been portrayed in all kinds of narratives, and therefore the gender distinction is still important. The Doctor might be quirky, but there’s no denying that the story is about him and that he makes the rules. People of both genders can be quirky, but the MPDG is a very specific kind of narrative trope that is applied to women; if it is applied to a man, I think it’s still referencing the way women have been treated in narrative, if that makes sense. Men can be manic pixies, too, but it’s rare to see the narrative use them in this way.

Whether you think the narrative uses Nao in this way is entirely open for debate, and I think you make some good points. It’s true that no one in the work comes across as a saint, and Nao is able to criticize Gregory’s “wisdom” on Japanese women, for example. I wasn’t really sure if all of Gregory’s erudition was meant to be taken seriously or not, but the end of the work made me think that maybe it was. Your point that the Gregory at the end of the work is no longer Gregory is well-taken, although he still comes across as fairly overbearing.

What you say about Steve as an outsider or an entry point is also well-taken; that makes quite a lot of sense to me, although I do think he has some long-suffering elements that fit into certain narratives about men knowing what’s best for women. Steve is confused by Nao, but he seems to know what’s best for her. I can see him as a creeper, too, though, now that you mention it. There’s some nuance there.

As for what you say about an entry point to OCD, this is what I like best about the work. When a vast majority of people don’t know that PO OCD exists, it’s really helpful to have almost any message about it out there, and I don’t want to sell Dillon short on that. My hope is that people will read this book and realize what their symptoms are, or know how to be understanding when others explain OCD. I think as a starting point, it can be very good, and, honestly, almost anything about PO OCD is better than nothing. But when a lot of people are taking the book as gospel, we have a big problem, and I wish Dillon had thought that through a bit more.

I think overall, we just have really different readings, but that’s a good thing!

Patrick- It’s not that I want to see the book in black and white terms so much as that I think the book presents characters and issues in terms that are fairly black-and-white. I don’t think that Nao is self-absorbed, but I think that the book presents her as being self-absorbed and even seems to punish her for it, if that makes sense. What I don’t like about the book is the ways in which it links OCD to self-absorption very subtly. There’s sort of an implication that Nao should be perceiving Gregory and Steve’s problems, at least to my eyes.

As for the ending, the issue for me isn’t that Nao is cured. Of course it’s possible to overcome mental illness with therapy, medication, and even alternative techniques. Joe McCulloch has an interesting take on the ending of the work based on his personal experience over at TCJ; I’m not sure it applies to OCD, but it’s worth a read if this interests you: http://www.tcj.com/this-week-in-comics-101712-yeah-thats-right/. At this point, I’ve also largely been able to overcome my difficulties, but I wish the book showed more explicitly how this might happen. As it is, it kind of implies that the car crash was all it took, even if that’s not what it’s trying to say.

Katherine- I absolutely agree. That colored a lot of the book for me. While there are other issues with it, that’s something I simply can’t get over. And Patrick, I see what you’re saying about the context of the book, but I think it’s still hurtful because it implies that she feels better about her OCD (whether or not she’s “solved” it), because she realizes that it’s just a thought process and that it is “her fault.” This is something that OCD sufferers nearly always know instinctively, and becomes part of the reason that they blame themselves for the disease, avoid seeking help, and worsen over time. Even if it wasn’t Dillon’s intent to make this come across as responsibility for the disease, his phrasing is really unfortunate and hurtful. Katherine really hits the nail on the head.

This is a lot and I probably forgot some things, but I have to get back to work now. Thanks for commenting!

I guess when it comes to the issue of the men in the book, just to be a bit more clear, I don’t think that the narrative tries to portray them as unequivocally good. It’s more that I think the narrative consistently takes them and their problems more seriously, and consistently suggests that Nao should be more attentive to them and more available sexually and emotionally. This is subjective, of course, but that’s what it comes down to for me. An issue of importance, not good and bad.

OK, I’m really getting back to work now!

Thanks for writing this, Emily — particularly where you take the hatchet to Gregory and Steve. I couldn’t believe how all the online praise seemed to give Dillon a pass on those two guys, or the triangle they form with Nao. (Actually, given the general level of gender awareness in our culture, I could believe it all too well). I found that stuff in the book gross.

Also — definitely agree with you on Nao as MPDG (and your response to Seth re: same)

FWIW, I read the sudden resolution via text page as cartooning failure, rather than any, I dunno, logocentric ideology. I figured Dillon must have got to that point and suddenly realised “oh shit, I’ve drawn 200 pages and I still need an ending that solves everybody’s problems and brings enlightenment…fuck it, I’ll just pull a Dave Sim”. That reading is promoted by, and in turn promotes, the overall impression that the ending is unconvincing and tacked-on

Great piece. I like your criticism of the way Nao’s intrusive thoughts are depicted visually, especially. Also, thank you for shoehorning in those paragraphs about the problem with affective criticism. This article sets a high bar!

Hey – I’m not super familiar with the Doctor, having just come on board in the last couple months, but I am familiar with the Ninth, Tenth, and Eleventh—and I’d say that the Eleventh’s series with Amy and Rory are not about the Doctor at all, but put him at his manicpixie wackiest entirely to the service of character development of Amy Pond (and to service of Rory so far as he is part of Amy’s evolution). Series 5 through 7.5 is Amy’s story and the Doctor is entirely present to serve the needs of her character.

And maybe that’s rare. The sense I get though is the the characters of a book are usually present to serve the development and self-realization of the protagonist. So women will serve that role in a book with a male protagonist and men will serve that role in a book with a female protagonist. Generally. And that seems alright to me. (Ensemble pieces are a bit more dicey. If Celine seemed present simply to provide the impetus for Jesse’s story in Before Sunrise/Sunset/Midnight, that would have been problematic.)

It seems right that Darcy should be an underdeveloped main character wholly present to propel Elizabeth to where she needs to go. And that’s how I read Nao, with Steve and Gregory serving Nao’s self-realization/fulfillment. That you read it in reverse is fascinating. I trust my own judgment over yours (simply because I know me and you are a stranger) but I could be entirely mistaken. Maybe Dillon left the book open enough that the characters can become reflections of who we are, the lives we inhabit, and the circumstances that govern our lives. We’re the two of us certainly approaching from different angles. I’m coming from a host of privileges: male, American, Protestant, northern European heritages, middle class, with the nearest mental illness being a grandmother I never knew (her illness took her violently). I don’t have as much at stake personally and maybe that gives me a distance from the work that disallows me from seeing things that others see.

I think that’s cool and it’s why I’m glad these discussions exist. I apologize for taking up so much of your time, but this was a pleasure. Thank you.

Hey Jones – If it helps, Dillon has expressed dissatisfaction with the four pages of text as well. Too much of a full-stop on the action. After considering all the reaction to it, he seems to view it as a misstep.

“It seems right that Darcy should be an underdeveloped main character wholly present to propel Elizabeth to where she needs to go.”

Are you shitting me? Would that literature were full of characters as underdeveloped as Darcy’s. His motivations and his character arc are more off to the side than Elizabeth’s, but Austen is maybe the best novelist in the English language, and she is very much able to give him a nuanced and layered character even if he is not always center stage.

Noah – Yeah, “underdeveloped” was absolutely the wrong choice. Really, what I meant to get at was the fact that Darcy, for how fantastically he’s developed, is still much less in focus than Elizabeth. And yes, I would love for more books to be filled with non-protagonist mains as solidly conceived as Darcy.

All right then. Just as long as no one is bad-mouthing Jane Austen.

My mental-illness experience, unlike Joe McCulloch’s and unlike Nao’s, has been resolutely anti-epiphanic. Not to go into it too deeply, but, like most people, I’ve Been Through Some Shit, shit that you might imagine would give me a better sense of perspective on life–and even if those experiences afforded me some temporary insight, the next shift in chemistry obviated any comfort or relief I felt, and the bad thoughts came right back.

Similarly, the revelation that he had a rare form of cancer that was likely to kill him didn’t make my father’s OCD any better. An adaptation of Buddhist practice did, so I have no issue with that aspect of the book–although the essential element of the treatment strategy was (surprise!) medication.

As for “it’s all my fault,” maybe context changes that line, but Emily’s reading suggests that it doesn’t. Maybe it’s ambiguous. The thing is, it’s not acceptable, to me, to be subtle, ambiguous, artistic about assigning blame for mental illness–especially because the idea that Nao’s condition is not her fault is contrary, as Emily pointed out, to the dominant cultural narrative about OCD.

Seth- I see what you mean about supporting characters; I haven’t really watched Doctor Who so I can’t speak to it much one way or the other (and it was a mistake to try to do so). For me, I think the problem is that it was meant to be Nao’s story, but it didn’t read that way to me (and it did to you, which is interesting to think about). Your distance from the work might disallow you from seeing certain things that I see, but it also allows you to see other things.

I guess for me what I take out of all the MPDG discussion is that it’s both underdevelopment of the character and narrative sidelining, and that’s been commonly applied to women. It doesn’t mean that there aren’t female protagonists and male supporting characters, but those characters, I would say, tend to have more of a life than their female counterparts and exist more independently, in general. There are exceptions to the rule, but I will hold fast on this as a gendered representation.

Jones- I’m glad you liked it! I think it’s a cartooning failure for sure that just happens to come across in an ideological way, but either way it’s just not great. And Seth, I didn’t know that Dillon regretted the decision to include the memoir. I thought I had read just about every interview with him but I guess I missed a few, so thanks for pointing that out.

subdee- Thanks!

And Katherine, I just want to say thanks again for commenting. I really, really appreciate it; you’ve said it better than I can and it’s a message that we need to hear over and over.

Two more thoughts about Nao as MPDG — first, what makes a character a MPDG is as much about the man she is helping self-actualise as her own character. It’s not just that Nao is Nao, it’s also that Gregory is Gregory — a sad sack who is considerably less physically attractive but who the MPDG is inexplicably attracted to. Gregory is played by Seth Rogen; Nao is played by somebody “hot” who is at least 10 years younger.

And the claim that we shouldn’t talk about MPDGs because there are men like that too…that’s like saying we shouldn’t talk about magical negroes because white people can give sage advice too, and isn’t it Spike Lee who is the real racist here?

I’ve talked some about the reversal of the MPDG trope in terms of Twilight especially,and also (in the same article) George in A Room With a View. I think switching the genders changes things around quite a bit (is the supershort summary.)

Or slightly longer summary; MPDG’s are about presenting a woman as a way for guys to self-actualize. This is gross, in that it subordinates the women’s story to the men’s. When you reverse the tropes, you very often end up having a story about a woman who sees a man as her entrance to being equal with men; that is, it becomes a story about individual response to structural sexism. That ends up working pretty differently.

Nahhhh, thank YOU for being so courageous and writing this amazing essay.

Whoa. Amazing essay and its angle is something that never hit me.

I will have to re-read Nao again and see how much my perception of it changes; it may stays like Seth or change drastically or little. Either way, great job and can’t wait to read more from you.

And a thank you to Katherine.

There’s one type of male MPDG that’s become a tiresome cliché: the chick-lit heroine’s peppy gay male sidekick.

Pingback: Comics A.M. | WonderCon wants ‘to get back to the Bay Area’ | Robot 6 @ Comic Book Resources – Covering Comic Book News and Entertainment

Emily,

This is a well-considered and forceful review, and I appreciate your comments on my TCJ review. That’s especially because I had a generally uneasy feeling about some parts of the book that you brought out in sharp focus in your review.

I also regret the way I worded the paragraph that you highlighted. I do know some OCD folks, and I badly mangled my intention in that paragraph. When I said Nao “couldn’t see” the problems that others had, I should have been clear that it wasn’t a matter of willpower, selfishness or ill-intent, but literally a matter of being unable to do so because of her illness.

Dillon took a big risk by doing this narrative about mental illness without being clear that it IS an illness, not a personality quirk or personal weakness/failing. That risk was exposed by the ending, but you’re right that Nao is the only character not allowed personal agency. The one time she actually **acts** (yelling at Gregory), she’s punished by Dillon when Gregory has a stroke. And while both Steve and Gregory are depicted as having limited agency during parts of the book (Steve can’t talk about his true feelings and Gregory self-medicates), you’re right that they’re both given cathartic, self-empowering endings. Nao just gets hit by a car, as though a good bump on the head was all she needed.

In the end, a set of quirks or a disease is not the same thing as characterization. And while Dillon’s sense of stylization is dashing and beautiful (and these are things not to be underestimated with regard to the overwhelmingly positive reviews, mine included), it does mask both the problems of sexism in the book and the poor choices made regarding the depiction of PO OCD.

You should pitch to TCJ sometime, by the way.

Rob- Thank you so much! This is such a kind and thoughtful comment; I’m glad that you saw it that way, and I really appreciate your clarification. I see what you mean and it makes more sense now. I also agree that there’s a reason the book has gotten such great reviews; it’s not a small achievement by any means and I think Dillon can do good work in the future.

And thanks for the invite. I’m still new to this whole “writing on the internet about comics thing,” but I would be thrilled to pitch something sometime. Thanks again for such a kind offer!

Also, Larry, thanks for commenting. I’m glad you found it worthwhile!

As for the MPDG issue, I think everyone else has said it (and thought about it) better than I can. AB, that’s an interesting point; I think it’s often true although the dynamic isn’t exactly the same. I’ll have to think about it a little bit more.

Emily,

Drop me a line at tmc (at) duke.edu and I’ll give you info regarding pitches.

Really liked this piece. Thank you for writing it

Pingback: Stories To Save Your Life: Graphic Novels on Mental Health | saraheknowles

I truly appreciate this essay and all the comments as well for how thought provoking and interesting they both are. It’s quite refreshing to read a review in which the author has such opposite readings to my own but is so articulate and politic that while I don’t agree with many of the interpretations I still get a great deal out of reading the essay. I I feel that there are a lot of positive aspects to Nao’s character development that are glossed over in favor of speaking only about the accuracy of the portrayal of her illness. There are lots of good points made here but I don’t think it is necessarily Dillon’s job to forgo a lot of, what I found to be, beautifully subtle and delicate narrative in favor of more highly specific descriptions. I appreciated the vagueness for it’s subtlety. But, I also understand the disease to some minor degree-mostly from reading about it with a few personal relationships as well. I think that, for me, a lot of the beauty of the tone would disappear if Dillon tried to make it a more like a guide to exactly what this specific disease is like. I love Allison Bedchel but I found Are You My Mother? a bit heavy handed in it’s need to portray therapy so accurately.

I think that when one has such a personal connection to a topic it is easy to lose some important perspectives. And your problems with his portrayal (or lack thereof) of PO OCD are totally valid and important. But, I think that there is an important element missing from both the review and the comments (correct me if I’m wrong but I didn’t see any.) The fact that this is a review of a graphic novel and there are no mentions of the artwork itself is truly sad to me. The quality of the art itself is a huge part of what a graphic novel is and if you mean to imply by your title that you give this book a One out of Ten stars or something that seems incredibly harsh to me. It’s basically saying that the quality of the art has absolutely zero bearing on the quality of a graphic novel and that the only thing that matters is the narrative. If you think the art is total shit- which I can’t see how anyone would but maybe you do and if so that’s totally valid too- but it would be worth mentioning. It’s the complete lack of mention that gets me and perhaps you meant this as more of an essay about PO OCD and it’s portrayal in the book but the title implies that you are in some way reviewing the book and I think the art and quality of art (whatever your opinion of that may be) is an important topic when reviewing or discussing a graphic work. It doesn’t need to be a huge thing- just a few sentences here or there would do. And maybe they’re there but I just missed them and maybe it’s because I loved the art so much that I found it a travesty that no one even mentions it.

I did get a lot out of your review and everyone’s comments and I’m grateful for the respectful and intelligent discourse. It’s a rare thing on these interwebs. Thanks for taking the time to read and respond to everyone and keep on writing and inspiring, Emily!