Ever since the moment, many decades ago, when my mom introduced me to Little Women, it’s been my pleasure to return the favor whenever I can. Sadly, the opportunities are rare, given what an informed and energetic follower of excellent midlist literary fiction Mom is. Zipping through The English Patient or People of the Book years before I get around to it, she waits patiently, reading list in hand, while I meander through Proust or Pynchon, linger in fiction’s demimondes, reading romance and erotica and writing my own.

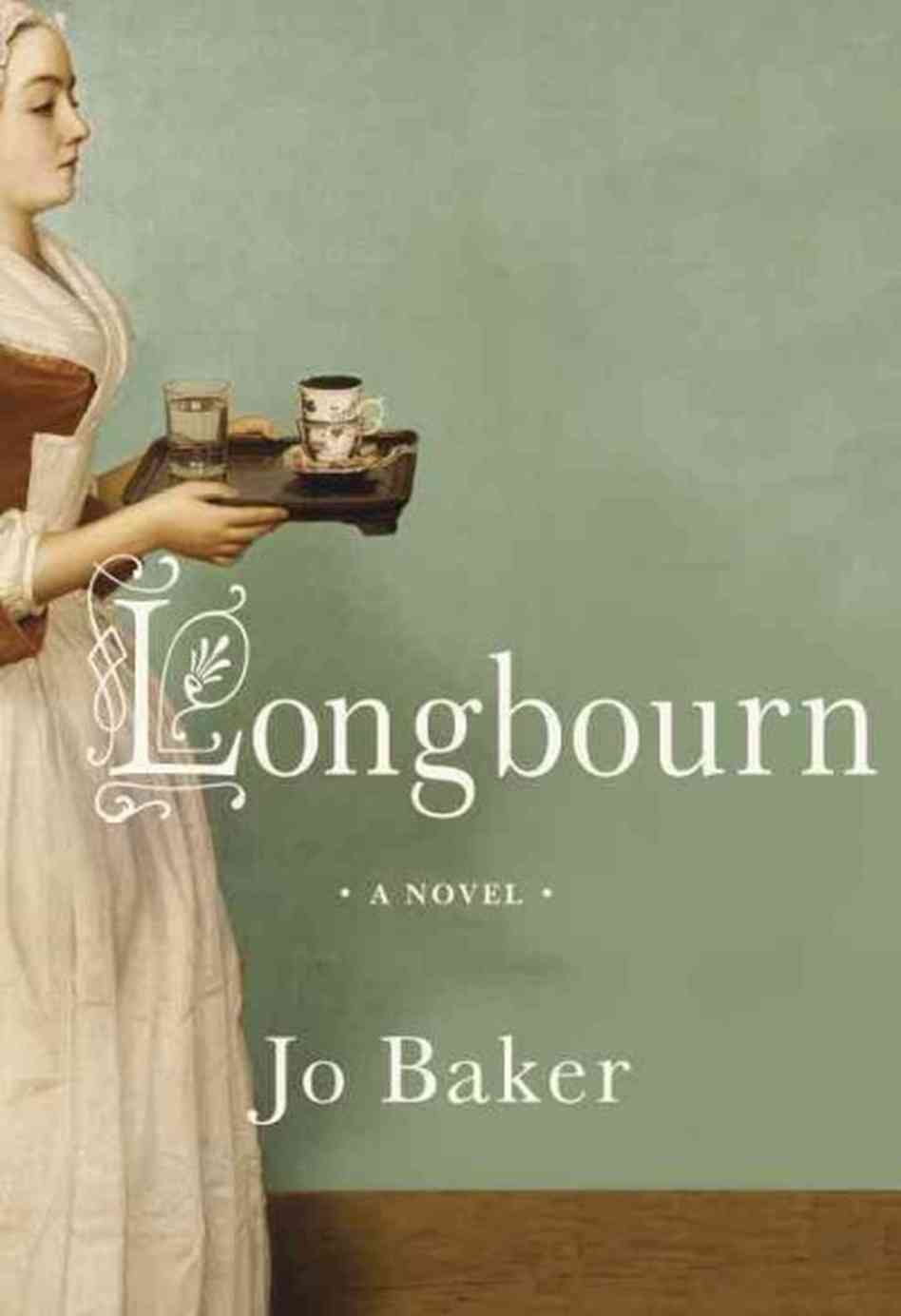

So it’s a special joy when we find common ground in a book of my choosing, as we did when I visited her recently, bearing a birthday present. The gift was a copy of Longbourn, Jo Baker’s stunning retelling of Pride and Prejudice from the point of view of its household servants. I also had it on my Kindle, so we settled happily at her kitchen table to read it together.

So it’s a special joy when we find common ground in a book of my choosing, as we did when I visited her recently, bearing a birthday present. The gift was a copy of Longbourn, Jo Baker’s stunning retelling of Pride and Prejudice from the point of view of its household servants. I also had it on my Kindle, so we settled happily at her kitchen table to read it together.

But as Mom turned pages and I flicked at my screen, we each were seized with palpable concern that things might not end happily for James the footman (“he’s so nice,” Mom sighed) and Sarah the housemaid.

Concern grew into anxiety. Were it not for the other’s presence, we each might have sneaked an illegitimate glance at the last page for reassurance. We were reading Longbourn the way Martin Amis remembers first reading Pride and Prejudice: “I… read twenty pages and then besieged my stepmother’s study until she told me what I needed to know. I needed to know that Darcy married Elizabeth… as badly as I had ever needed anything.” We read like the “Smithton women,” the sampling of readers Janice Radway interviewed in Reading the Romance, tearing through their most cherished recreational reading. Animated by our lust for a happy ending, Mom and I were reading like romance readers, even if the novel in question was one clearly marketed as literary fiction.

.

And why not? Lots of mystery and horror, spy and crime fiction titles have lit fic cred bestowed upon them even as they’re appreciated for their characteristic genre frissons. Stephen King is regularly celebrated in The New York Times Book Review while remaining our supreme magus of high creepiness. Why shouldn’t a literary novel be read for romance’s particular pleasures? Longbourn – already justly recognized for its handsome writing and clever, deeply informed take on Austen’s fiction and Georgian England – ought also be praised for what it shares with my shelf of books all named something like To Love a Duke: the ache and throb and richness of yearning for a happy-ever-after ending.

Before taking on the romance novel or Longbourn’s complicated genre provenance, though, we should remember what a vexed and fluid thing “genre” actually is. Situated at the intersection of marketing categories, reader interaction, academic turf wars, and who knows what else, genres bump up against or devour each other. Like the glowing spheres in my time-waster computer game, Osmos, they emit gravitational fields, travel in orbits, clash, collide or piggy-back on each other.

You can read Longbourn as literary or historical fiction. Mom had been wanting to read it as “the Upstairs/Downstairs Pride and Prejudice,” and you can certainly read it as Austenlandia, which category probably had the most to do with its “set[ting] the British publishing market on fire… when it went on auction.”

Loving the book as I did, I think I read it in all of the above genre categories as well as a romance novel. In fact, a big part of the pleasure I took in Longbourn was not that it transcended genre but that it seemed to participate in so many of them. Part of the adventure was negotiating the category clash. And let’s not forget Baker’s own account of how she’d classify her book:

I think of Longbourn — if this is not too much of an aspiration — as being in the same tradition as Wide Sargasso Sea or Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. It’s a book that engages with Austen’s novel in a similar way to Jean Rhys’s response to Jane Eyre and Tom Stoppard’s to Hamlet. I found something in the existing text that niggled me, that felt unresolved…. [having] to do with being a lifelong fan of Austen’s work, but knowing that recent ancestors of mine had been in service. I loved her work, but I didn’t quite belong in it…

Is there a name for this literary tradition (that also, notably, includes Geraldine Brooks’ Pulitzer Prize-winning March)? I usually wind up calling them “no-I’m-not-Prince-Hamlet books,” but surely we can do better. “New Historical” fiction? No, that’s too academic (though it does recognize the wealth and depth of Baker’s historical spadework). I’m open to suggestions.

Baker isn’t the only reader who’s been niggled by a well-beloved text. How many of us do belong in the worlds we love to read about? “Caesar beat the Gauls,” Brecht said. “Did he not even have a cook with him?” In fiction as well as history, we identify with the principle actors, those whose names have survived. How do we make room in a text for the selves the text turns a blind eye to? (And how to keep that Brechtian PC hectoring tone out of our voices?)

A brilliant English professor I know once assigned a class of undergraduates to write about the servants in Pride and Prejudice. “And if you ask what servants –” I’m told she added – “read the book again.” But Austen makes so few direct mentions of servants that even after a careful rereading, they’re hard to spot. By my search of Pride and Prejudice’s digitized text, we read three times of a Mrs. Hill; once of “the two housemaids”; once each of a butler and a footman. Yet meals are cooked and served; messages delivered; somebody has to drive the carriage to this or that social event. Shoe-roses for the Netherfield ball are fetched in the pouring rain “by proxy”.

As in the New Testament, you know these servants by their works. “When a meal is served in Pride and Prejudice,” Baker tells us in an afterword, “it has been prepared in Longbourn. When the Bennet girls enter a ball in Austen’s novel, they leave the carriage waiting in this one.” Downstairs events are mapped upon the satisfaction of upstairs needs in Austen’s text.

And so Longbourn begins on a washday, before dawn in the village of the same name, of which (Jane Austen tells us) the Bennets “were the principal inhabitants.” The acres of fluttering muslin we’ve come to love on our PBS screens are shoved into washtubs: just think how much fabric must be washed, ironed, and hung out to dry in order to clothe a Georgian gentleman’s wife and five daughters for a week. Add that gentleman’s shirts, stockings, and high white cravats (stiffened with rice starch, Baker tells us), the sheets, pillowslips, napkins – and the servants’ underwear as well. It’s no wonder that the washing begins at four thirty, when the pump still painfully cold to the touch, especially for Sarah, the older of the two housemaids, whose hands are afflicted with chilblains.

I think Jane Eyre had chilblains, or some of the children at Lowood did; I once wrote a romance hero who almost gets them when he forgets his gloves. But I was never moved to look it up before now, when I learned from Wikipedia that exposure to cold and humidity “damages capillary beds in the skin, which in turn can cause redness, itching, blisters, and inflammation.”

That the malady can be cured in seven to fourteen days doesn’t help a housemaid bound to the wheel of weekly laundry. Add insult to injury when that same housemaid is obliged to scrub away three inches of mud caked onto Lizzy Bennet’s petticoat. In the opening scene of Longbourn, physical hardship reflects and amplifies emotional travail. Generously taking the lion’s share of the washing (the younger housemaid’s still a child), Sarah’s nonetheless as angry as any lively twenty-something would be, not merely at the discomfort but the invisibility of her situation. Chafed by cold and damp, she seethes with what James will describe as a “ferocious need for notice, an insistence that she be taken fully into account.” The irony is that as she scrubs away the mud from Lizzy’s petticoat, Sarah is stealing our attention from one of literature’s most beloved literary characters and her charming, hoydenish, country walks. Though we begin our reading eager to learn more about the Bennets (and though we do), Longbourn’s stealth dynamic is to make Sarah’s story the one we care about.

It’s a serious perspective jolt, and in more ways than one. I was more than a little discombobulated, for example, to realize that from Sarah’s angle of vision, there’s not such a wide distance between Lizzy and Lydia. Jane Austen appraised her characters according to an unsparing, Olympian ethical calculus, but the view from below stairs is more utilitarian. Because cook and housekeeper Mrs. Hill is worried about keeping her job after Mr. Bennet dies, shy, awkward Mr. Collins is besieged with cake and cosseting. For Sarah, alive with her developing sexuality, the Bennet girls constitute a sort of ladies’ magazine, a compendium of competing styles of female attractiveness; it’s here (rather than as a moral actor) that Lizzy wins hands down.

“Bright-eyed and quick and lovely… always ready with a what-do-you-call-‘em, a “witticism”: Sarah ponders Lizzy’s example as she plots how to attract the interesting new footman’s attention. “Natural manners were always considered the best,” she concludes, having “heard Miss Elizabeth say so.”

That “natural” manners are matters of laborious construction, is, of course, another irony, applied by Baker with Austen-esque subtlety. Since Georgian “naturalness” took some resources to pull off, sadly, Sarah’s “natural” greeting falls through. Meanwhile, James has his own reasons for staying aloof. Which situation not only drove Mom and me into a frenzy of reading to find out what could be keeping him from loving Sarah as much as we did, but which caused us to agree, a few chapters in, that this wasn’t an “Upstairs/Downstairs” book after all.

For while an “Upstairs/Downstairs” production like Downton Abbey purports to set two classes in satirical opposition, Upstairs is typically afforded primacy. For every Downton dressing-table vignette – Lady Mary’s charming, rueful bitchiness in the mirror of Anna’s elegant decency – there’s a view of Lady Mary through the adoring eyes of that butler guy with the eyebrows. In Longbourn’s dressing-table scenes, on the other hand, Sarah’s too distracted (both by work and her body’s demands) to pay more than dutiful attention to Lizzy.

And yet Elizabeth Bennet’s story remains a serious and important one, and a pillar upon which Longbourn is constructed. In her study, A Natural History of the Romance Novel, Pamela Regis has called Pride and Prejudice “the best romance novel ever written”. The right of a woman to choose a mate for love instead of material convenience is its great theme, Austen’s complicated take on the issue one of her great legacies. Unsentimentally engaging the limits of the possible, she created memorable loveless marriages as well as unforgettable happy ones. Even among the gentry, Charlotte Lucas doesn’t have the resources to hold out for the kind of love she knows she’s unlikely to get.

Will Sarah also settle for second best, we wonder – the question complicated by the fact that her second best, the Bingley family’s half-black footman, is a much more attractive alternative than Mr. Collins. In a deft stroke, Baker has the Bingley money coming from the West Indies, like the Bertrams’ in Mansfield Park. Bearing his master’s name, the freed slave Ptolemy Bingley might be Charles’s half-brother. In any case, Sarah could do a lot worse than this wonderfully named character. Tol is smart, sympathetic, quietly damaged, drop-dead gorgeous, in love with Sarah, and a glamorous reminder of a wide world she hungers to see. But he’s not James.

So, once again, Mom and I kept reading, loving the historical savvy, exquisitely layered period detail, and social critique, but still reading for the love story. Or to be more precise, we read it as social critique enlisted in the cause of its heroine’s right to have a love story. A story recuperated from the blank spaces within the best romance novel ever written ought itself to be a romance novel.

If Longbourn genuinely is a romance novel. Which brings us back to those complicated issues of genre, this time having to do with romance fiction.

It’s a noisy, enthusiastic discussion these days, fueled rather than inhibited by feminism. You can pick up on the debates at academic symposia, a peer-moderated journal, a host of blogs, and an energetic and inclusive professional association, Romance Writers of America (RWA). Romance fiction is a multimillion-dollar industry, a site of academic turf-building, and a ongoing sisterhood of remarkable, smart women (If anybody had told me in the radical feminist 1960s….). Encompassing vampire romance, Amish romance, romance for threesomes or same-sex partners: the genre is wildly protean in its themes and variations. Self-published on the web or mass-marketed: the business is pragmatic and wide open to entrepreneurial innovation. And yet (and quite differently from, say, science fiction) all its proponents are pretty much on the same page when it comes to what makes a romance novel a romance novel.

On its web-site RWA insists that the romance genre need a central love story and an emotionally-satisfying and optimistic ending: “In a romance, the lovers who risk and struggle for each other and their relationship are rewarded with emotional justice and unconditional love.” Pamela Regis’s Natural History of the Romance Novel expands upon these themes by identifying eight “narrative events” that must be present: definition of society (“always corrupt, that the romance novel will reform”); the meeting between the heroine and hero; their attraction; the barrier to that attraction; their declaration that they love each other; point of ritual death; recognition that fells the barrier; and betrothal.

Students of the formalist tradition (via Propp, etc.) won’t find much in Regis that’s unfamiliar. But trust me; I’ve been trying to bust her categories for years and they work. Simple, so economical they seem in danger of dissolving into tautology (but somehow don’t), they constitute a remarkably functional and hard-headed set of conditions by which to judge whether a work “of prose fiction” that tells “the story of the courtship and betrothal of one or more heroines” actually counts as a romance novel.

Gone With the Wind, for example, doesn’t make the cut: Scarlet and Rhett’s recognitions of their love for each other, Regis says, are too ill-timed to fell the barrier between them. GWTW readers may tack an imagined mutual recognition and happy ending onto the text (as I still do after multiple screenings of Quentin Tarantino’s Jackie Brown). But imagined elements don’t count, and RWA would doubtless agree. If GWTW were entered in the RITA competition (the organization’s yearly version of the Oscars), it would have to in the category of “Novel with Strong Romantic Elements,” rather than Contemporary, Historical, etc.

In the case of Pride and Prejudice, Regis’s categories are clearly a much better fit: Elizabeth Bennet does survive both her ritual death (Lydia’s disgrace might well have been the death of all the other Bennets’ marriage prospects); and she and Darcy do indeed achieve a timely, barrier-breaking set of recognitions. It was, however, as I was reading Longbourn that I began to wonder about Regis’s first, seemingly anodyne “narrative event”: the definition of society (“always corrupt, that the romance novel will reform”).

Reform, really? No reader could gainsay the importance of Elizabeth Bennet’s right to love and marry Mr. Darcy, but it’s rather a stretch to think their union strikes much of a blow for the “reform” of Georgian society. And in fact, upon picking up Regis this time, I noticed that as she continues her argument, she restates the notion of “reform” quite a bit more softly. “The scene or scenes defining the society establishes the status quo which the heroine and hero must confront in their attempt to court and marry and which by their union, they symbolically remake.”

Right. Symbolically. Northrop Frye says it better in his Anatomy of Criticism when he assigns to the comic/romantic mode the work of re-integrating its characters into their social milieu (in opposition to tragedy, which alienates its suffering protagonist). As a brilliant realist, writing about the times she lived in, Austen doled out rewards and punishments according to the desserts of those times, but so exquisitely and exactly that she erected a romantic ideal on the foundation of the real. What actually happens in the final pages of Pride and Prejudice is a social/moral reordering of the status quo, each character precisely rated according to whether (or how often) they’ll be received at the gates of Pemberley in the years to come.

What then of Longbourn, written from our present purview of an earlier era whose social wrongs are painfully manifest and palpable? Does the love story hold enough primacy over all that historical actuality? Can a book that re-imagines Austen’s story with such keen historical double vision fit into the romance novel genre? Or is it perhaps after all merely a literary/historical/New Historical/ no-I-am-not-Prince-Hamlet/Austenlandia novel with strong romantic elements?

Like Elizabeth Bennet – and like Sarah – I’m still holding out for romance.

Firstly because Longbourn is not only an informed and touching book, it’s a sexy one – not very explicitly, but in a way that accords sex serious and intelligent consideration, along the way of developing both the love relationship and the world around it. I’ve stressed the harrowing details of daily labor below stairs. And believe me, there’s lot’s more where that came from. But in the matter of sex and sexuality I have to disagree with Sarah Wendell, on the pages of her popular romance blog, Smart Bitches Who Love Trashy Books, when she fails to find any “justice or balance of circumstance in the narrative to take the sting out of the reality of the servants’ circumstances.” By my reading, the erotic passages in Longbourn provide, not only a respite from “painful realism,” but a credible, if difficult, road to RWA’s necessary conditions of “emotional justice and unconditional love.”

Not to speak of some lovely, sensual writing: “She was dreamy with her new understanding, lulled with contentment, not thinking beyond the pads of her own fingers, the tip of her tongue.” Yes, there’s serious suffering yet to come; in fact James, who “knew better” than the just-awakened Sarah, thinks of their situation as “a beautiful disaster.” But not thinking beyond the pads of her own fingers? Those same fingers we’ve seen so painfully afflicted with cold and damp? You’ll have to excuse this romance reader for a moment as she shivers with pleasure, and this erotic romance writer as she loses herself in admiration, both for Baker’s writing and her smarts about female sexuality of the period.

Longbourn imagines a credible, if rather sad, erotic innocence for the Bennet girls (at least the ones who aren’t Lydia). A down side of Regency class privilege was certainly its fetishism of female purity. Straining against the limitations of what they ought to be – “smooth and sealed as alabaster statues underneath their clothes” – bored, curious, and adventurous girls of the polite classes might well have become Lydia Bennets while their more proper sisters make do with “uneasy half-suspicion of what men and women might do together, if they were but given the opportunity.”

Of Jane Bennet, moping around the house after the Bingley’s have decamped, Sarah thinks: “Sit and wait and be beautiful, and wan. Sit and wait and be in love. Sit and wait until Mr. Bingley shook off his sisters and returned to claim her. That was how things worked for young ladies like Miss Jane Bennet.” While for people like herself and James, “nobody looked askance at a big belly at the altar, nobody cared so long as it was under plain calico or stuff, and not silk.”

Comparative sexual freedom for the lower classes doesn’t come close to balancing the scales of justice, but it affords some nice compensations. And in the matter of “unconditional love,” I offer a few of the book’s simplest, most gorgeous sentences, from perhaps the book’s darkest moment, when James is gone and Sarah doesn’t know how to find him, and when the kitchen at Longbourn is all abuzz with news of Lizzy’s engagement to Mr. Darcy, with “carriages and the Lord knows what”: “Sarah went back to her work, her jaw tight. She would have been content with so little. She would have been content with just his company.”

And I’d also be pretty deeply content with only that last sentence, if I didn’t have an additional and final argument for Longbourn as a romance novel (and a wonderful one) that’s both like and unlike the one whose gaps it fills.

For if Pride and Prejudice ends its final chapter at the boundaries of Pemberley, Longbourn ends its penultimate chapter in the same place, with Sarah, who’s been lady’s maid to Lizzy, leaving “quietly, unattended, by a servants’ door,” Pemberley standing “silent and self-contained” behind her. Pride and Prejudice revels in its power to create an ideal – even a “reformed” – family within the gates of what it deems a great good place (Wickham never received, nor – as the text hints rather than comes right out and says – Mrs. Bennet either). But at the end of Longbourn, an astonished Mrs. Darcy will also have to do without Sarah, who’s off in search of James.

There would be others out there, on the tramp. There always were, around the time of hiring fairs and quarter days, these great tidal shifts and settlings of servants around the country.

I don’t know much about “these tidal shifts and settlings,” but I do know something about the massive economic uncertainty in England toward the end of the Napoleonic Wars. And I also know that great migrations of the poor take shape during uncertain times. And so it makes sense to me that it’s among nameless, shifting human tides (perhaps – if you want to do a Borges take on it – among the unnamed characters from other novels) that this novel begins to find its just and satisfying resolution. A resolution less perfect, and far less conclusive or secure than that of Pride and Prejudice, but one that creates, if not an ideal family, a redeemed one.

And if I’m giving you something like a peek at the final page – well, that never stopped a romance reader from reading all the way through, just to make sure.

______

Pam Rosenthal’s romance novel The Edge of Impropriety won Romance Writer’s of America’s 2009 RITA Award for Best Historical Romance, and Playboy called her erotic novel, Carrie’s Story (w/a Molly Weatherfield), “one of the 25 sexiest novels ever written.” Her website is http://pamrosenthal.com

Not sure all readers here will be familiar with your writing Pam — so it’s worth mentioning that (at least in the novel I read) you do a good bit of Upstairs/Downstairs yourself, with romance plots for both servants and the upper crust.

Is that typical in regency’s these days? The Cecelia Grant book I read also was very aware of class issues.

Thanks for mentioning that, Noah. Yeah, I’ve always been interested in servants, and try to make them visible in my romances (hey, I also often have a Where’s-Waldo Jewish character hidden among all those Dukes of Earl). The heroine of the first romance I wrote, THE BOOKSELLER’S DAUGHTER, is a scullery maid in pre-revolutionary France; I did a ton of research about master/servant relations for that one.

And yeah, the historical romance writers I like the most are the ones who write about class issues. Cecilia Grant, Tessa Dare, Joanna Bourne, Sherry Thomas, Carla Kelly come to mind. I can’t say the genre encourages it, but one’s conscience sometimes demands it; it takes a lot of contortions to do it and wind up with your h&h both socially aware AND richly rewarded, and I love those contortions.

But the best Downstairs romance writer by far, imo, on these issues is my romance-writing pal and partner in crime, Janet Mullany, whose MR. BISHOP AND THE ACTRESS is also laugh-out-loud funny.

Pingback: More about Longbourn, and Why I’m Claiming it for Romance | Passions and Provocations

I really loved reading this, and hope to pick up Longbourn, and add my thoughts sometime. I have some aversion to the Austenlandia, (a new term for me,) all those films and rewrites and sequels and +zombies orbiting around Pride and Prejudice. I was actually more concerned about it being a piece of Austenlandia than it was as being romance novel. This piece does a great job of qualifying that the book transcends that, and justifying that Austenlandia isn’t the worst place for a piece of literature to be either.

But back to romance not getting the same lit fic creed– I agree. I think this idea has come up a few times recently on HU, and I’m excited to see writers keep pursuing it. My head’s in the same place, after having written about A Room With A View… On that note, I love how you talk about the experience of reading romance, the anxious gunning for the end… I wish there was more written about that too, and how it flows over into reading other genres as well.

I’m interested in the argument that you can figure out a formula for romance. Isn’t it somewhat self-fulfilling, though? I mean, I think lots o people would identify Gone With the Wind as a romance. You’re saying that there are institutions set up that wouldn’t agree, but why should we believe those institutions and not all the folks who think differently?

I guess I’m somewhat resistant to the definition of “emotionally satisfying and optimistic ending” because for me those two things can be at odds. If the ending is too gratuitously optimistic, I don’t find it emotionally satisfying; instead it depresses me. I don’t think that’s just me either; romantic weeper endings with hankies have to have an audience, right?

Thanks for this. Not only am I interested in reading this (being a fan of Austen), but it gave me a book to recommend to my mother-in-law (which’ll win me some points).

The premise makes me think of Edward Said and his contrapunctual reading of Mansfield Park, but rather than look at the casual acceptance of the material benefits of slavery and imperialism, look at the concerns of romance from the perspective of a servant class that goes widely unacknowledged, but whose labor is crucial the parent novel’s central premise.

Thanks for the kind words, Kailyn. I’m not crazy about Austenlandia as a name, but one hears it, and it does the job.

The thing about LONGBOURN that blew me away was not that it challenged a lot of the pretty-pretty-pretty of our white muslin wishdream world — although it did do that. It’s that Baker expands Austen’s world and it’s still Austen’s world. As though enlarging a photo-image and revealing the picture in more details; as though Sarah and James were THERE, or COULD have been there, but were just too tiny to see — as opposed to having to change the existing structure of the photo-image in order to make room for what YOU want to see in it about.

And when you realize that that’s what Baker’s doing, you also realize what a realist genius Austen was, to have created that world in the first place. Nabokov said something like “Tolstoy’s prose keeps pace with our pulses.” There’s a version of the same thing in Austen as well; something about how she organizes time and space — both in the world she portrays, but also in the rhythm of her sentences.

So when you read LONGBOURN, you get to reread Austen, a less pretty-pretty-pretty Austen than we’re used to seeing, but in many ways a more accurate one than we’re used to seeing. What we get is something a lot more compelling.

>>I guess I’m somewhat resistant to the definition of “emotionally satisfying and optimistic ending” because for me those two things can be at odds.

Hey, Noah if *I* start reading a romance novel and the ending seems too easily immanent, I feel something I can only describe as “despair.” So I do know what you’re talking about. Not every “optimistic” ending of every text is “emotionally satisfying” for every reader, though I do have to admit that I read and write the genre from far left field (even if not far enough left for you, from your response to THE SLIGHTEST PROVOCATION).

But I do buy the orthodox definitions, because when they work for me, they work for me. The romance novel is a celebratory genre, ending at a wedding. The marriage will enter real time, and the spouses will age and bad events happen, but the novel ends at that celebratory moment where positive and productive union is possible and the community recognizes this. It belongs to the calendar of festivals, not the calendar of work days (I’m working on an essay to this effect).

There is a kind of aggressively populist strain in the romance argument that wants to align the genre’s form with how “the people” (and not you big city snobs) read narrative. I try not to get too hung up on that.

>>romantic weeper endings with hankies have to have an audience, right?

Yes, but Avon and Harlequin don’t print them.

“Yes, but Avon and Harlequin don’t print them.”

Sure…but why do Avon and Harlequin get to define what a romance is? They don’t have exclusive rights to the word or anything.

I’m thinking about Jason Mittell’s argument that genre’s are defined not just by those who read them and know about them, but by folks who are more marginal to the genre communities. Like I said, I’m pretty sure that there’s a large number of people who see GWTW as a romance, and I don’t think there’s necessarily much reason to discount them in favor of Avon and Harlequin.

I agree with a lot of that My husband calls the broader definition of romance “the romance field” — and for me, the romance field extends, for example, to KILL BILL 2, lots of Colette, stuff I loved in my adolescence like Francoise Sagan, my own most successful book, the pornographic (and I think very romantic) CARRIE’S STORY. I think of these forms as positive or negative ions, highly charged. The stable atomic center, though, qua Harlequin or Avon, is the book that ends happily, the story, as I said in my essay, of “a heroine’s right to have a love story.” Romance readers, I think, recognize that form as a pre-feminist, historical achievement.

Which isn’t to say, once more, that the atomic center doesn’t spin off a highly charged field.

Very thought provoking, thank you! And I am wondering if you would enjoy Jane Austen and the Archangel. Jane finds love.

So, Pam, I’m kind of wondering where romantic comedies fit in for you? It seems like in terms of audience and general profile, they have much more influence in determining how people see or don’t see romance than romance novels do?

I also enjoyed reading this, Pam. It has been…well, decades since I read Austen, but now I’m very intrigued by Longbourn (and your own work as well)! I am especially interested in the claim that “we read it as social critique enlisted in the cause of its heroine’s right to *have* a love story.” This is exactly the kind of conversation I’d like to see taking place in discussions of romance and African American historical/literary fiction, and not just over the matter of genre definitions. In keeping with Noah’s point about GWTW, I can certainly see how some of the conventions of romance circulate through canonical black literary texts like Their Eyes Were Watching God, The Color Purple, or Beloved and help to shape the stakes and tensions of these narratives. Yet many readers are resistant to these sorts of readings as if it will threaten the importance of the social/historical issues and questions of identity formation that are central to the plot. I don’t know if this sounds like an apples to oranges comparison, or if I’m broadening the publishing industry’s definition of romance too much (maybe that’s not such a bad thing). But in any case, I couldn’t agree more that the structures of genre fiction shape “literary” texts in ways that have yet to be fully and satisfyingly acknowledged.

Don’t know JANE AUSTEN AND THE ARCHANGEL, but willing to try it, Pamela. My friend Janet Mullany has also written 2 novels where Jane not only finds love (as a vampire) but learns from the experience how to write the kind of free indirect discourse she more or less invented and taught the rest of the world how to write. Funny and smart.

As for romcom, Noah, it’s weird, but romance writers almost never talk about romcom. I don’t know why, but it’s a very separate sphere. What interests me more is the “remarriage comedies” of the 30s-50s that Stanley Cavell wrote about in THE PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS. I think these have a lot more to teach the romance genre.

As for Osvaldo’s comment about Said and Mansfield — I think his noting the source of the Bertrams’ wealth is important; and I’ve seen academic critics do a terrible job with the information. The back of the Norton edition of MANSFIELD PARK is filled with tortured essays about what slavery means in the novel, none of which, imo, work.

And Qiana, thanks for your comments. I’m in agreement.

” I think these have a lot more to teach the romance genre.”

Well…my point was kind of that for the majority of people, rom-com is the romance genre. So it seems like if you’re trying to create rules or formulas for the romance genre, leaving out rom-coms (which are actually the ground zero of the genre for the majority of people) is a problem.

I actually think rom coms are horrible for the most part. Some of the difficulty is that they don’t actually have that feminist commitment to the woman’s love story often; they’re much more focused on the guys’ experience, often the the exclusion of the woman’s.

And Qiana I totally think Their Eyes Were Watching God works as a romance, both in terms of the plot and in terms of its compulsive readability. Probably part of why it had some trouble getting traction as a literary classic (though it’s well ensconced now.)

It may be true that “for the majority of people, rom-com is the romance genre.” But once again, Regis’s book is called A NATURAL HISTORY OF THE ROMANCE *NOVEL*; Avon and Harlequin don’t make movies. I don’t pretend to understand how this works; I don’t know why there is so little crossover between today’s popular romance novel and the movies. There are some adaptations for the Lifetime channel, but not so many (8 by Nora Roberts sounds like a lot, but not when you realize she’s written more than 200 books).

It’s not so much that I’m trying to “create rules.” I’m observing that the formal criteria other people have articulated for the romance novel work rather better than you’d think, given how certain other genres work (qua Jason Mittel and John Rieder whose work you helpfully recommended). Lots of interesting questions here.

I wonder if the stability is in part because the genre has been so closely associated with a couple of publishers?

Medium lines and genre lines can also be kind of blurry, incidentally. For instance, I’ve had conversations where I tell people, “comics aren’t very popular,” and the reponse is “yes they are! Look at the Avengers movie!” Which, on the one hand, you want to say, the Avengers movie is not a comic. But on the other hand, if this keeps happening, people obviously do see superhero movies as comics to some degree. So separating romance novels and rom com films may seem like a clear division because of medium, but it doesn’t necessarily have to be.

>>..So separating romance novels and rom com films may seem like a clear division because of medium, but it doesn’t necessarily have to be

True, and this has been interesting, but I hesitate to weigh in with more generalizations because I’m really quite a peripheral romance writer (4 novels makes me pretty much a piker). Anyway I’m really grateful to you for the energy of your thought on these issues, and I’ll be hanging around this neck of the woods from time to time.

I’m incredibly late to this party, but thanks for hosting, Noah. I have lots of thoughts, so I’m just going to throw them out there.

1–Thanks so much for this piece on Longbourne, Pam. I’ll definitely check it out and your work as well. I’ve yet to read an upstairs/downstairs romance, but I’m looking forward to Mullany’s work as well.

2–Noah pushes back on RWA’s definition of romance. He says,”I guess I’m somewhat resistant to the definition of ’emotionally satisfying and optimistic ending’ because for me those two things can be at odds.” And how can you argue with that? Except, I would argue with that. I find Pam’s description of the happy ending (the couple in love and together at the end) as the “stable atomic center” compelling. Noah seems to want to move that center and I would ask, why? What would we get out of that move? An acknowledgement that romance often doesn’t end happily? Sure, but these stories aren’t about that. These stories are about romances that work, where the promise of the first blush of attraction is fulfilled. Defining the genre to include all those stories that have romantic elements, but end in heartbreak (no matter how satisfying) seems to me a capitulation to the cynicism of readers on the margins of the genre. Romance is unapologetically impatient with your cynicism. It’s got a happy ending to get to.

3–I think romance novelists are better at romance than Hollywood because romance novelists actually enjoy the genre and know it and consume it. I’m not convinced that’s true in Hollywood and we get some pretty crappy romcoms as a result. Not all crappy, but so few as satisfying as I find a Lisa Kleypas novel.

4–OMG GWTW. Don’t you think people want to claim that book/movie as romance so they can hang on to the passion and sexiness of Rhett/Scarlet and ignore the dysfunction? They want what romance readers get in their novels–the emotional satisfaction of the couple happily together–and are happy to ignore much of the novel to get it. Again I ask, what would we get by classifying GWTW as a romance rather than something else, say, a historical novel with romantic elements? Would it serve the novel in some way? Open it up to a bigger audience? What?

4–And to Qiana’s points–I think investigating the influence of genre on literary fiction is crucial. But again, I wouldn’t call the novels you named (Beloved, The Color Purple, Their Eyes Were Watching God) romances (mostly because the love story is not central to the plots of these novels). I am interested in what romantic elements add to the narrative projects of these novels. How does a romantic relationship between Paul D and Sethe help Morrison write about the humanity of the enslaved, the emotional brutality of slavery, the necessity of community, the power of memory? You’re right when you say readers are resistant to foregrounding the romantic elements in AA literary fiction for fear that we ignore the “important” stuff. But that’s one of the reasons I am resistant to moving the “atomic center” when discussing genre definitions (as tiresome in romance as it is in comic studies). If I’m telling a story about black people in a genre that demands a happy ending (not bittersweet, not emotionally satisfying in its tragedy, not a tearjerker), what kinds of stories about black people can I craft? Can I tell a convincing love story against the backdrop of slavery? Of Jim Crow? Can I tell a convincing, emotionally satisfying story that doesn’t ignore those things but also doesn’t foreground them? Studying AA romance (and this is taking the conversation far afield from Pam’s original essay) means moving the atomic center of the AA literary tradition from tragedy and struggle to joy, from survival to living (to quote Solomon Northrup). I like the challenge AA romance poses to those of us who study AA lit.

5–And finally (because I really need to be grading finals), and this is just me working through ideas I’m writing about right now, definitions of romance depend too heavily on articulations of formal elements of plot and not enough on what I think are the more crucial (if more intangible) elements: desire and vulnerability. Romance absolutely depends the successful narration of desire–we need to believe that the two people in question want each other, in a singular way, in a way they do not want, could not want, someone else. But we also need to believe their vulnerability, their willingness to lay themselves bare to and for each other (something Rhett and Scarlett don’t do, with good reason, as they’re both kind of wretched). Vulnerability is rewarded in romance novels. Risking that kind of pain is rewarded. We have to believe the risk to be satisfied by the reward. Going back to AA literature, when is vulnerability ever a good move for a black character? How often is that ever rewarded? What happens when you put a black character in a genre that changes the rules for black characters?

And, with that, I’ll end this ramble and tackle some grading.

” because I’m really quite a peripheral romance writer (4 novels makes me pretty much a piker).”

Hah! I haven’t written a single romance, and don’t even read it all that often, yet I’m happy enough to burble away in comments sections!

Consuela:

” a capitulation to the cynicism of readers on the margins of the genre. Romance is unapologetically impatient with your cynicism. It’s got a happy ending to get to.”

1. You ask what one would get from moving the center…then you go on to suggest that readers “on the margin” of the genre are cynical, and that their investments are somehow compromised or illegitimate. Suat’s talked a bit about how romance in Asia (or at least in Singapore where he lives) is much more focused on tragic endings; are all those folks cynical? Is their experience of the genre somehow illegitimate?

In that vein, I think there are several reasons why it might be useful to think about genre more fluidly. For one, it just seems like for some purposes it might be more accurate — if you’re talkign about what people like in romance and where the center is, for example, it seems like the fact that rom coms are (I believe) more popular than anything else is probably important. And, for another, it seems like it opens the discussion up to talking about non-formal ways of defining the genre (which you argue for yourself.)

2. That’s interesting…but you’re assuming the point at issue it seems like. That is, you’re defining romance as if it doesn’t include rom coms. And Hollywood certainly hasn’t always been bad. Unless you’re claiming you don’t like Bringing Up Baby or His Gal Friday? (And I liked this recent romcom, which doesn’t end in a marriage or a romance, but I think fits the genre, and isn’t cynical.)

4. I don’t have any love of GWTW (haven’t read the book, saw the movie long ago, but find the racial politics in particular repulsive.) But again, the point of thinking about it as romance seems like it would be accuracy. You seem to agree that people do think of it as romance. It seems like if you’re talking about what the romance genre is, and lots of people see it as this, and genre is socially defined, then dealing with GWTW’s presence in the genre seems like it would be important to think about. You sort of point some ways that might be the case in your reading, it seems like? that is, you say that readers want to ignore the emotional dysfunction to get to the romance. But isn’t emotional dysfunction often a bug rather than a feature in romance? Certainly it is in 50 Shades, which, again, was hugely popular.

4. That’s a great formulation (romance providing a challenge to AA lit)…but surely if you were willing to see romance as more diffuse, it could go the other way as well? That is, AA lit could challenge romance’s commitment to a (completely) happy ending. (And why should that challenge be defined as marginal?)

Ack, sorry; still thinking about this.

Consuela, have you seen Kailyn’s piece on romance and E.M. Forster here?

It’s in part about how the romance plot, or the romance ending, can be oppressive and stifling rather than freeing. If the romance center is romance as defined by Harlequin, then Forster’s criticism undermines the genre, or rejects the genre. But if the genre is more fluid, then Forster’s criticism is actually within the genre. From that perspective romance might be defined as the issues it deals with, or by what it considers important, rather than by a single solution to those issues. Similarly, Watchmen (which I know you don’t like) doesn’t have to be a criticism of the superhero genre, but can instead be seen as part of the genre, with a particular take on the central issues of goodness and power.

Consuela, thanks so much for your thought-provoking post, and for making my point so much more by extending it to questions of AA lit. I hope you continue working on these questions and keep me in the loop. IASPR (International Association for the Study of Popular Romance) would love to hear from you if it hasn’t already (I don’t keep up as well as I should). I also agree with you about the cynicism of recent rom-com (though I’m grateful for the reminder, Noah, about DRINKING BUDDIESs, which I see my husband has added to our Netflix queue). And I loved your blog, Consuela, and hope that Cate has continued with Harry Potter.

I continue to agree that the romance novel ought to maintain its commitment to the full-valence happy ending (and that the charged ionic spinoffs will take care of them selves). And I think your thoughts about AA literature would be a great way to go, in order to respond fully to Noah’s challenges (which deserve a better response than I’m capable of giving at the moment).

And Noah — re rom-com, I want to turn again to Stanley Cavell’s PURSUITS OF HAPPINESS, which discusses both BRINGING UP BABY and HIS GAL FRIDAY as “remarriage comedies,” and makes lots of extraordinary points about what this set of films tells us about sexual politics in the period between first and second wave feminism. I used a lot of his ideas about the remarriage comedy when I was thinking my way through THE SLIGHTEST PROVOCATION.

I hadn’t made the connection between His Gal Friday and the Slightest Provocation! That totally makes sense.

I should read Cavell’s Pursuits of Happiness. I’ve enjoyed some of his other work (and written about it a fair bit)but haven’t looked at that one.

Brilliant, Pam. Like you and your mother I read desperately for James and Sarah’s happy ending even through the beautiful prose that made me want to linger.

To your GWTW observation; I think GWTW also fails Regis’ model because the love of the main characters does not alter their world. War does.

Thanks for this piece!

Hi Kate! And thank YOU!

Yes, I totally agree with you about GWTW, and actually, I think Pam Regis says something like that too. This business of what it is and is not possible for love to alter, though, in the romance novel, is worth its own study — and it will happen very differently depending upon whether the novel is set in a historical, a contemporary — whether it’s chicklit in a recognizable venue or cozy women’s fiction in one of those towns where no one bowls alone.

Also (though I don’t know if we want any spoilers here), I’m wondering what you thought about the late pages in the book devoted to Mrs. Darcy’s life at Pemberley.

This comments section gets more and more interesting.

Weighing in biographically, I don’t have too many friends who read romantic fiction, although plenty who read YA. This is partly my age group– my twenty something friends decompress by reading things that remind them of being 14. However, the description of my friends reading YA fits exactly to the description of reading romance– a championing of certain relationships, anxiety about the resolution, voracious reading. These are the same friends who watch rom-coms, mostly for grounding, or to reconnect. I’ll be home for a night, and my roommate will say, “Want to watch a silly girly movie?” The badness of the production, plus the lack of realism, becomes part of the expectation and indulgence. It also privileges the communal experience– lets laugh and swoon over this together– over any immersive, or even escapist program in the film. And here is where the two conjoin– I think people read the YA for the collective experience of reading it, out of a fear of missing out, and also that the books will yield a silly movie to share with your friends.

I’m not sure if romance is shared the same way– from my experience, I haven’t seen it, although I’ve been to enough Renaissance fairs and Highlands Games to have seen the long autograph lines. But its always seemed to me to be a private pleasure. Not just because the books are erotic, but because reading is one of the truly private activities many women have. And this might make finding another reader who shares the same books, and yearns for the same endings, more thrilling. It might have something to do with the ridiculous success of 50 Shades– the private thrill intermixed with all that pseudo-event, FOMO lambast.

I think many women, my friends included, use romance as a way to reinvest and resync with society. Its as if the marriages at the end symbolically stand for the viewer’s recommitment to a stressful, unsure world. I think this is something many people prefer to perform communally– at a movie, or a movie-like book, as opposed to internally. Its a trade-off of intensity for safety-in-numbers. And maybe that communality takes some stress off of the happy ending– sad or unresolved endings can function like as romances, as its still groups of people watching together.

I guess the last line should be:

And maybe this communality takes the pressure off of the happy ending– sad or unresolved endings can function as romances, since groups of people watch it together, proving the coherence of society.

At the same time– could Twilight have had an unhappy ending? Or The Hunger Games? I think the Sookie Stackhouse books did, and didn’t people hate that?

Gosh. It IS getting more interesting. Thanks so much for that, Kailyn (and let it be known that I’ve just checked A ROOM WITH A VIEW out of the library).

Romance readers definitely do the communal thing. On blogs like http://http://smartbitchestrashybooks.com/ and lots of other places, like conferences (I once read that a reader fainted when she saw author Lisa Kleypas). Levels of irony vary widely — the Smart Bitches are a lot like you and your friends settling in to watch a movie, but also knowing that it means a lot to them or they wouldn’t be doing it.

But then there’s also the private thing — and perhaps that far outweighs any group activity; I wouldn’t know.

As for THE HUNGER GAMES. A whole new thread. But just for openers, DID it have a happy ending really? I’m so much older than its demographic, I have have to wait like 6 years for my older granddaughter to read it and explain it to me. But I was saddened that it was so so so awfully post-ideological before its readers ever get a chance to be smartass ideologues.

Lots more to say here.

HG’s happy ending is somewhat ambiguous. Katniss is unwilling to say she’s in love with her husband, and in general still seems to be suffering PTSD. It’s kind of an interesting take on your points in that Room With a View essay, Kailyn; the book sort of dumps the romance plot on her, and she doesn’t have any escape, though she’s not really happy about it.

Do you know how big romance novel readership is, Pam? Or how much a successful book sells? As Kailyn suggests, it feels like it’s smaller than a lot of these other things…though I wonder if that’s in part self-determining (i.e., Twilight really could be a romance — is part of the reason it isn’t because it’s so successful?)

>>Do you know how big romance novel readership is, Pam?

It’s… big, Noah. Here are the Romance Writers of America statistics: http://www.rwa.org/p/cm/ld/fid=580

I think a lot of this is confusing because of cross-overs, e-publishing, etc these days. I don’t think this includes Twilight, for example, but I’m not really sure.

As for how many copies a big seller sells… as I’ve said, I’m a piker, so I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about it. But I do have a cousin who likes to ask why I’m not signing 7 figure contracts like Sylvia Day.

Hmmm…not that big. 1.43 billion sounds like a lot, but the top five grossing films together make that much by themselves it looks like. This is suggesting that the Twilight series alone (books only) has sold 85 million copies, so if each sells for 10 bucks or so, you’re getting into the neighborhood of 850 million dollars for those books alone, or more than half the entire take of romance fiction in a year. (I bet Twilight is not included in that romance fiction number.)

So…I’d say romance is a significantly bigger fish than comics, but still kind of small potatoes by the scale of mainstream media.

I know a lot of people who hated LONGBOURN, but after I read your review, and Jayne’s from Dear Author, I decided I had to try it. Would I find it grim? Anachronistic? Would it massacre Austen’s characters in order to fit into the author’s preconceived plot?

Nope, nope and nope. I loved the whole damn thing. And I think your review summed up my reactions pretty well. Out of all the Austenlandia books I’ve read, LONGBOURN is the best, hands down. It expands Austen’s world, but is true to it at the same time, which is really an amazing feat when you think of it. I didn’t find it grim or tedious; it’s extremely readable, though it’s less a romance, and more of a literary historical novel with an emphasis on social issues, a la Hilary Mantel.

I find the Regency period really interesting, but I get so tired of the romance world’s obsession with dukes and the cushy, unbearably privileged lives of the upper crust. I could so relate to Sarah and her world, and her interactions with the Bennetts. I *loved* how Sarah feels like she becomes literally invisible when faced with the likes of Bingley and Darcy. If I came face to face with Darcy too, I imagine I would feel the same way.

Re your financial accounting, Noah: what I think is interesting is that romance makes more money, bookwise, than sci fi or mysteries or literary fiction — but it has very little crossover. Again, no blockbuster movies made out of Nora Roberts books, though they are all the time from other genres including literary fiction. I think this is interesting, and I’m not sure why it is (and Jennifer Weiner’s arguments aren’t apposite — hey, she may not be reviewed, but she’s adapted). Something about the romance novel wants to stay a novel. Which is not true for the YA blockbusters. OR of course 50 Shades, but don’t get me started on 50 Shades.

And Joanne, I also loved how Sarah feels herself invisible in Darcy’s presence. What’s interesting as well is the implication that being the mistress of Pemberley won’t be any walk in the park, as it were, for Lizzy.

Huh; I didn’t realize it made more money than sci fi or mysteries (though more than lit fic I would have guessed.)

I’d guess the difference re no adaptation has to do with literary credibility, and probably also with doubts about female audiences sustaining a movie. Possibly also something to do with Hollywood being male dominated, so you get nostalgia for male genre films among creators rather than for female genre product. Some things (like 50 Shades and Twilight) are massive enough hits to overcome those barriers, but not too many.

Pingback: Isn’t It Romantic?

This is well after the fact – I just found this post via a Smart Bitches link. But I can’t resist commenting, because this is one of my pet topics. I call what you’re calling “no-I-am-not-Prince-Hamlet” novels “Elpenor” stories. Which has the advantage of brevity, and loses nothing in pretension.

I get it from Seferis (who owes a great deal to Eliot I believe), and his cycle of poems exploring the story of an oarsman in the Odyssey. Elpenor gets drunk on Circe’s roof and falls off, breaking his neck. No one even notices he’s gone, until he begs Odysseus for proper burial when they meet on the shores of the land of the dead. He does eventually get his proper burial, don’t worry, but of course this is wildly inconvenient for Odysseus, not to mention all the rest of the crew who don’t survive the story.

Granted, it’s an obscure name, but then it’s still a pretty small genre. Elpenor has got to be the earliest, and most perfect example of how most of us would show up in a heroic tale, if at at all: simply to fuck everything up for everyone else by doing something embarrassing. If he’s remembered, it’s for being forgettable. I must have read The Odyssey a dozen times before I found Seferis, and I took zero notice of Elpenor (although I did remember the dog, who gets even less screen time, go figure).

I love the idea of these books, but the reality of them…I’m still delighted it exists, but I found Sargasso Sea even less interesting than Jane Eyre, which is saying something. I’m still on the fence about reading Longbourn, but this is a pretty compelling review. I’m more excited to find your books, actually.

Also, I’m with Noah – GWtW is a romance novel, albeit a crappy one. To say it’s not a romance novel because it doesn’t fit current critical categorization is to say that the ccc is doing a poor job of reflecting reality. But I’m admittedly impatient of academia, and I’d far rather read a romance novel than a new Linnaean system for them.

I like “Elpenor” book. Thanks. And do try MARCH, which is a particularly excellent instance of the genre.

And thanks as well for the heads-up about the SB piece at http://smartbitchestrashybooks.com/blog/longbourn . I love SB Sarah’s generosity re giving space to contending opionions, and I think the reviewer makes one very important point about how LONGBOURN is not a romance — that the very appealingness of a romance setting is part of what makes it so, and there’s simply nothing appealing about Georgian life below stairs. I post an argument there from my viewpoint, but I admit it’s a weak one.

As for “Linnaean system” — that’s not how I see it. But I’ve already made my own arguments for why I buy the restrictive definition (even though in fact, I like to read and write on the borders).

” that the very appealingness of a romance setting is part of what makes it so, and there’s simply nothing appealing about Georgian life below stairs.”

I think that’s super problematic. What about Beverly Jenkins romance featuring the underground railroad? Those don’t get to be romances? Different people find different things appealing; defining “appealing” as wealthy and white just doesn’t seem ideal to me.

>>I think that’s super problematic. What about Beverly Jenkins romance featuring the underground railroad? Those don’t get to be romances?

I hope it is problematic, Noah. It is for me. But I’m not going to ignore the Krispy Kreme aspect of reading romance.

“I’m not going to ignore the Krispy Kreme aspect of reading romance.”

Amusingly enough, due to an egg allergy, I can’t eat Krispy Kremes.

I should try to finish that Beverly Jenkins book I started. I wanted to like it, I think what it’s doing with romance is really interesting, but it was written badly enough that I kind of couldn’t hack it (not as bad as 50 Shades, not as bad as John Grisham, but still not good.)

Soooo before you make any more proclamations about Beverly Jenkins and her writing, I do hope you’ll read more of her work. I have revisited Something Like Love and Through the Storm recently and found enough historical context and Krispy Kreme to satisfy.

I only talked about the one book! (I can’t even remember the title…it’s whichever one you recommended.) I’d be willing to try another one; which of those two would you suggest?

Something Like Love – that’s worth a try, a few hours of your time. Of course, now you have all these expectations and here I am giving you the side-eye, so you’re bound to hate it. That’s fine. Just don’t go pulling out the Grisham scale yet.

I’ve ordered it too, Qiana. I think this discussion is particularly interesting when it asks questions about what the romance community calls POC romance, as in this blog post: http://dearauthor.com/features/letters-of-opinion/poc-romance-and-the-authenticity-question/#comment-665428

That’s great, Pam! I’m eager to hear what you all think. Thanks also for the link to the post on POC romance. I’m going to grade a few more papers and then really dig into the conversation in the comments.

Pingback: My turn to say Happy New Year » Risky Regencies