The word “draftsmanship” is the loud, boozy, best-friend’s-sister of the artistic lexicon; available to all, understood by few. It’s a word which has come up in recent reviews of Art Speigelman’s exhibit at the Jewish Museum in New York. Some critics have raved over Speigelman’s draftsmanship, others have pooh-poohed it. The word itself seems misunderstood by some readers and critics or perhaps its older meaning is no longer even applicable in modern comix and illustration.

Draftsmanship is the quality of someone’s drawing (not just their rendering or painting). Like many qualities, it is not strained, it droppeth as the gentle rain of heaven and soaks the pages of both those that give and those that take. There is both good and bad draftsmanship and here’s the crux: how do you tell them apart?

In our post-modern, relativistic times, where nothing is certain except the fact that nothing is certain, readers of a philosophical bent will spit up their breakfast pablum at the implications of the above question. My reply to them is simple: if you refuse to make judgements, that in itself is a judgment and you’re probably oppressing someone, somewhere with your double-plus-judgemental refusal to make judgements. Naturally, my own judgements are non-judgemental, that’s the temporary prerogative of all soapboxes. I have no doubt that many HU readers will bring their own, equally sturdy soapboxes to the party later on and deliver some equally non-judgemental counter-judgements.

Good draftsmanship is an accurate, visually logical and harmonious depiction of reality. No genuine, long-term success in drawing is possible without first mastering realistic figure drawing, no matter how symbolic the style. The ability to make a human being look human or a horse to look horsey or a Princess telephone to look princessy — regardless of the level of symbolic distortion and compression — that is the basis of superior draftsmanship. But that is only part of it.

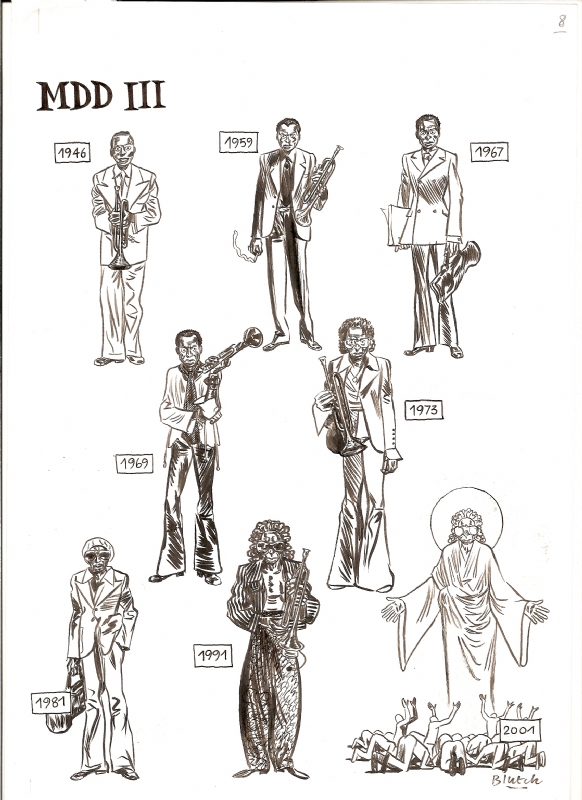

Draftsmanship is not just making clean contour drawings, and it is not at all about copying photographs. Good draftsmanship is the harmony, accuracy and design of reality processed through the eye and expressed through the hand. It can be as telegraphically crisp as a Japanese ukiyo print or as exuberantly messy as one of Blutch’s brilliantly inked pages.

Good draftsmanship means that everything looks good, even when it looks ugly. This is where things get slippery. Our eyeballs operate by the logic of a non-verbal grammar and a good drawing is always, without exception, “spoken” in this abstract language — otherwise it is visual gibberish. I think that for comix readers and critics — many of whom seem to prefer using literary techniques to analyze comix — this concept is a head-scratcher. Perhaps this is one reason why so few artists write comix criticism; the verbalization of visual rules for even a professional audience is tricky, for a general audience it’s nearly impossible at times.

So, in art-school parlance, good draftsmanship means depicting reality with complete design fluency on every level. Any symbolic compressions of reality are designed so that the trained, so-called good eye is always satisfied by the parts and the sum of the parts. The core mark is always reality.

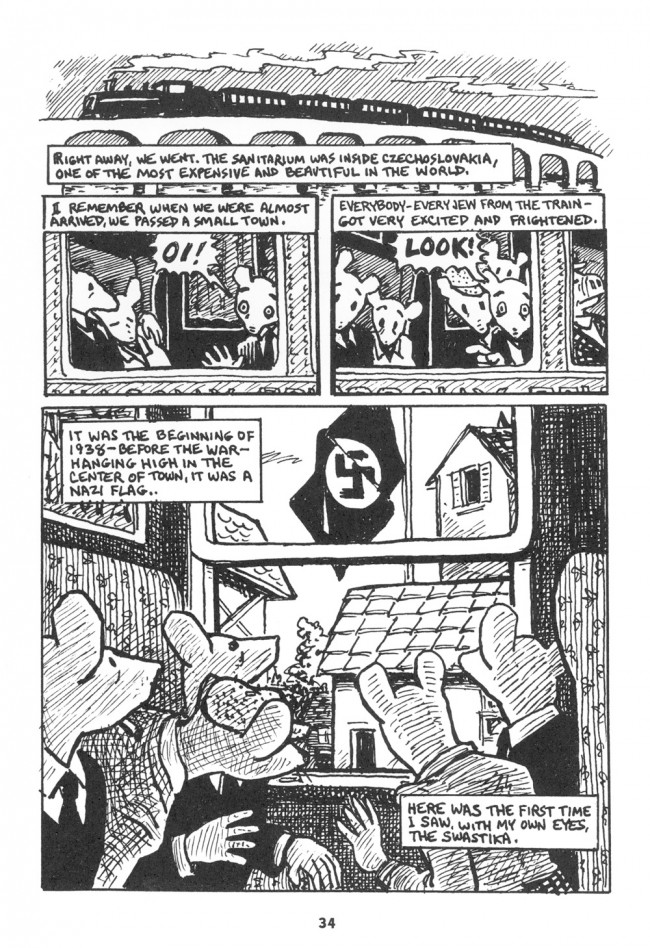

In any case, let’s look at a page from Maus, a page specifically posted by one critic as an example of the high quality of Spiegelman’s exhibit. Maus is many things, most of them good … but the draftsmanship is not.

The drawing of individual elements, such as the mouse-heads, is ungainly, even for cartooning. It is not that they should look more like real mice, that would be silly. The shapes/textures/lines are all where they should be to facilitate general navigation but they seem somehow squeezed into place. Taken individually, many of the shapes are inelegant and unsteady and note one thing: there are precious few lines of beauty.

Much of the detailing — clothing, hands, shading — is turgid and clotted, an effect exacerbated by the mono-width linework. Monowidth line-work needs air to breathe, and if you must cramp it, it must be fastidiously designed on every level, not just the over-all page level.

The rendering of volumes necessary to show the thrust of objects in space is often crude … example: the far-left mouse in the final panel needs his cheekbones and orbital bones indicated fluently. Yes, it’s a cartooney mouse but then why is it hatched? It would have been better to use a few simple interior contour lines to delineate the subsidiary planes.

In general, if one wants to use a weak, monotone contour system with fast, cursory crosshatching, the accuracy of shapes must be perfect. Here, the optically long lines (mostly describing backgrounds) are trembly and indecisive, the curved lines (mostly describing animate objects) lack the snap and bravura of the classic line of beauty. With pen and ink, one must always make a decision about how much of the hand’s presence should be visible on the page. You can go the slow Hergé route and hide the hand entirely or you can take the fast Herriman route and let the hand’s muscularity and nimbleness run amuck. Spiegelman’s inking style favours expressiveness but his draftsmanship betrays his aims. His hand is going faster than his eye can think.

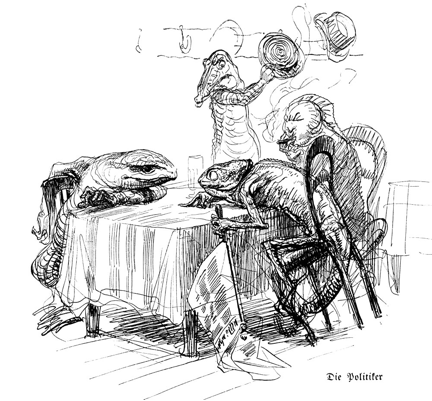

Heinrich Kley comes to mind as the successful epitome of this style of draftsmanship (see the two illos above). His hand is nervous but his eye is confident, thanks to his draftsmanship, his mastery of reality. In Kley, one senses the shape governing every line, even if the line is still searching for it. His hand is confident of the eye’s automatic guidance. Shapes and lines are rhythmically linked — a basic tenet of good visual grammar.

But in this Spiegelman page, the shapes are not “magnetizing” the lines in the same way, his nervousness stems from a lack of confidence in internally visualizing the reality being described. Roughly speaking, the visual, reality-based grammar governing the naturally pleasing agreement between contours, volumes and lines is too weak to please the eye consistently.

Spiegelman is not a superior draftsman, and I doubt if he himself thinks that he is one. Frankly, who of us are really good draftsmen? Not I … and it is not even necessary for Spiegelman’s purpose. He has made a living in the publications field for a long time and knows the score: do the best page you can at the time and above all, make it fit the story. There are better looking pages in Maus and in other works of his.

In fact, his usual style of story-telling does not require good draftsmanship and in a work such as Maus, a certain visual crudeness is more emotionally effective than a cleaner, crisper hand would have been.

Spiegelman’s work has never been about draftsmanship anyway, he’s a verbal illustrator, especially pre-Maus. He is also, to the eternal gratitude of everyone who makes comix in North America, the guy who made us at least semi-respectable to both a better class of reader and the people who send us royalty cheques. Younger readers have no idea how difficult it was to get the NYC suits to take you seriously before RAW began cracking the glass ceiling.

Most American golden and silver and iron-age corporate comix were nothing more than the step-and-repeat of modular, symbolic marks designed to rubberstamp the reader’s eyes into a stupor. Draftsmanship took a backseat to speed. And the draftsmanship of many contemporary comix is even more laughable in its absence. Too many North American comix are made by talented writers who cannot get into print by writing alone and must take up cartooning to tell stories. And the bar for comix submissions is lower than other fictions simply because the bar for visual competency is often set by non-visual editors, readers and critics.

Cartooning is now the default mode of drawing in North America, in both illustration and comix. It’s cheaper to purchase because it’s easier to execute and doesn’t require expensive, specialized training. And most cartooning is poorly drawn since the level of symbolic reduction is usually so extreme that the slightest defect is multiplied ten-fold and spoils the entire effect.

In any case, as I get older and crankier, I care less and less for the stories and thematic concepts of most comix, I look at only the pictures. My Holy Grail is a sequential art where the drawing is the meaning* as much as the story or words, perhaps even more so, to the point where the visual grammar will express a story in its own universal language. In fact, sequential art is the only popular visual art form which has the potential to utilize draftsmanship at this level, to make the medium and the message precisely the same. Music, architecture and dance still do this regularly. Why not comix?

*I think that Matt Madden’s experiments in constrained comix, his Oubapian work, is a major step in this direction. The implications of what he and others like him are doing may result in comix evolving into genuinely visual, absolute art at last. And to those that think that contemporary gallery art has this absolute value, I beg to differ. Any visual art form which requires a verbal explanation to understand the “message” is not visual art at all.

____

Mahendra Singh’s website is here.

Very satisfying and refreshing to read this. Well done.

Kley reminds me of Carlos Nine. As I keep saying, Carlos Nine’s comics needs translation into the english speaking market really badly. He blows me away with his sheer talent…

http://carlosnine.blogspot.com/

<<<>>

I hope and expect that fewer artists will be willing to work with non-artist writers who allow their credit to supercede that of their artists in the visual medium of comics. I’d say that writers who get involved with comics that do not make sure their artists share equal credit: the Kirkmans, the Gaimans, the Azzarellos, Ellises and Milligans—had bloody well better learn how to draw for themselves.

The Carlos Nine art is very nice … the Hispanophones have always favoured good draftsmanship.

About artist/writer collaborations … it’s important to remember that marquee-value authors’ names on the cover sell comix. The artists’ names rarely have the same impact on the buying public.

This particular kind of comic– “where the drawing is the meaning* as much as the story or words, perhaps even more so…”– is something that I’ve working hard to take into account as I get my next reviews ready to post. I guess I see it less as a holy grail, and more as undiscovered territory. I suspect that these kinds of comics may already exist, but can be unlocked through a different kind of ‘reading,’ one that prioritizes visual over verbal elements. But it sounds like you’ve been looking for this a whole lot longer than I have, and haven’t found them so far. Which is a little disheartening.

I think its crucial that comics creators become more thoughtful about draftsmanship, and how it has been traditionally understood. I’m skeptical about whether it’s value system (good drawing, bad drawing,) remains intact in the service of narrative. You bring this up when you say that Maus might not have been as emotionally affective… but could it be more than this? Isn’t there something troubling, or unethical, to depicting terrible things with a sort of heart-melting beauty?

I don’t think good draftsmanship needs to mean “beauty.” Metal bands are extremely technically proficient, generally, but the resulting product isn’t beautiful in the sense that that’s usually understood, I don’t think. Francis Bacon could really draw; again the result of that skill isn’t something that’s beautiful, quite (at least not in the way beautiful is usually understood.)

Have folks seen Kyle Baker’s Nat Turner? Mostly wordless; I wasn’t really sold on it, but wonder what others think.

Kailyn: I can think wordless comix, poetry-comix and Oubapian comix have much to offer … in time, young artists will move things forward.

A value system in drawing is 100% necessary. Otherwise, drawing will go extinct very quickly. The ability to look at any sort of drawing and analyze its good & bad points is 50% of being an artist. The other 50% is figuring out how to use this knowledge on one’s own work.

Draftsmanship isn’t always beautiful in the usual sense … Alack Sinner is beautiful drawing, but what a grim look. Ditto some of Katchor, Panter … Grosz …

I suspect artists who want to be taken as seriously as Gaiman and all should learn to write or co-write. That’s what they do in the manga industry and in newspaper comics.

In my experience, many editors don’t take artists seriously as writers. The less experienced editors assume that only a MFA or J-school grad can write.

I feel my bile rising … must take “medicine”.

Also, in terms of the ethics of drawing…I think the kind of punk-rock ostentatious refusal of skill is a claim to authenticity in Maus. In part, that is a move to reveal “real” ugliness. It’s as mediated and self-conscious as beauty would be. Whether that’s a good or bad thing is up for debate, but it’s packaging the Holocaust either way (which is presumably at least part of what’s at issue in not wanting it to be beautiful.)

Increasingly, artists are becoming aware of the importance of completely generating and retaining control over our own work. Collaboration could’ve been a productive way of working if the writers weren’t greedy about credit. As I have said before, the artists generate a tremendous amount of the narrative content in comics, even if working from full scripts. Fair credit isn’t about selling points, it is about rights of co-authorship. And frankly, if you don’t understand or care about art and are writing and/or reading comics for the text value alone, perhaps you should be writing and/or reading prose books.

Exactly, NB … Maus would never look right as a slickly drawn work … but it’s the “refusal of skill” idea which unsettles me in other works.

As current trends continue, when everybody refuses skill, will skill finally be the ultimate refusal?

Many younger artist reject the plasticity of mainstream comics, the dehumanized product-ness of assembly line production by expendable pieceworkers, and the look of digital lettering and color. And for good reason—they is made so to suit the purposes of corporate character/properties.

But, there isn’t quite the same point to “refusal of skill” if one didn’t have the capability in the first place. Gary Panter can draw very well—his “ratty line” is a choice. In Art’s case, drawing does not come easily to him in any way. Basically, I think that Maus may be rationalized by Art as fitting a “printing same-size art” purpose but more accurately, he is such a perfectionist that the only way he would have been able to complete such a long book is by publishing pages that look to me more like rough layouts than finished pages—look at the short early version of Maus that ran in Marvel’s Comix Book—it is much more finished art, but if he did it all to that degree, he’d still be working on it.

“they is”—whoops, urk

James, artists don’t sign up to draw Sandman (a work for hire book by a writer driven imprint) because they expect or want “rights of co-authorship.”

If the artist isn’t a co-writer- then they didn’t start with a blank page like the writer- and that may mean that their work, however spectacular, isn’t going to be as valued by fans- it might be seen as “merely” interpretive.

This is why I’m skeptical the problem is a matter of credit, and I suggest artists become co-writers or writers so they are involved at the blank page stage of the project.

I mean, it’s interesting that you think the problem is merely one of credit, but I’m skeptical.

I would like to add to the Pallas/James discussion … If the work is not licensed, it’s usually the writer’s decision to share fees and copyright.

Those generous writers who do so shall stand among the blessed ranks of the Elect, when the Ultimate Deadline drops.

Your attitudes are destructive to the nature of collaboration and a good part of the reason why any decent artist would be a fool to work with a writer who they can’t absolutely trust to do the right thing. If we were talking about cinema, it would be clear that no film would ever be made by a creative system you consider to be correct and fair. But because it is comics, some think artists should be happy to be abused. Believe me, I will not mourn when the mainstream completes its self-destruction and when none of your “blessed elect” of writers that cannot draw can get anyone who can to bring their “blank pages” to life.

Many big name writers, Gaiman, Moore and Morrison, Ed Brubaker and Brian Bendis, for example, actually can draw and many got their start in comics that way.

I don’t actually see evidence of artists fleeing the mainstream, (don’t Marvel and DC have more artists asking to work for them than they can employ?) nor do I see a vision of the movie industry where the director doesn’t “steal” much of the credit for themselves, so I’m going to have to disagree.

I’ll also point out you are putting words in my mouth… I never said anything about what is “correct or fair”. I only offered an alternative theory why artists are sometimes not taken as seriously as writers by fans.

People have been predicting the death of the mainstream for decades… it seems like wishful thinking.

The contractual arrangements that any artist makes are their own lookout … whether work for hire or licensing or royalty/copyright split, it’s up to the artist to say yes or no depending on the circs. Quite often, the writer has no say in the matter.

Writers who cannot draw as just as trustworthy or not as artists who can’t write, it has nothing to do with the situation. A smoothly functioning, simpatico team does just as good work as the solo auteur. In fact, when the team is in the right groove, they have the added benefit of multiple, objective viewpoints to improve each other’s work.

And you are both wrong, at least as regards Vertigo—-“creator-owned” meant (they no longer allow such projects) that the rights were split between writer and artist, but those rights weren’t bequeathed by writers from the goodness of their hearts. They were contractually stipulated, which is how I was able to successfully get Karen Berger to redesign the spines of the Vertigo Crime books, when they had initially left the artists off in violation of our contracted rights. Sandman may be work-for hire, but it is is credited as a collaborative creation. Gaiman’s ongoing cover credit hoggery is enabled by many artists who are happy to have the benefit of the sales, but they do none of the rest of us any favors in setting a bad precedent. Likewise, The Walking Dead is co-authored by three people but often, writers and some licensees name only Kirkman as creator. It is sad and typical that so many writers about comics are text-centric and subsequently prejudiced against the concerns artists, as you are.

Anyone who thinks that good sales and hence, resultant contracts, can be gained by an artist NOT allowing a marquee author to hog the cover is not getting the point.

Non-creative people have been hogging bylines since the Book of Genesis … do you really think anyone would have even heard of the Bible if it had some Jewish scribes’ names on the cover instead of You-Know-Who?

Two things I saw at Sarah Horrocks tumblr a few minutes ago…

(1) Alex Nino’s piece here isn’t wordless but it could easily work that way…

http://www.raggedclaws.com/home/2011/02/05/look-here-read-just-passing-by-by-alex-nino/

…why don’t people rave about Nino more? He’s AMAZING!

(2) Mahendra, you might enjoy this piece by Zak Smith about the art that deserves coverage…

http://zaksmith.tumblr.com/post/65978524988/67-no-wait-68-tips-for-art-critics

…I’m not sure I’d agree with everything, but there are some things that are good to hear after being exposed to the BBC’s and The Guardian’s (and many others) idea of “relevant” art for so long, even if they are too far in the other direction. It takes a pop at people like Koons (who was discussed here recently).

================

At the risk of sounding like a traitor to artists, I think some writers do all the things that make a comic worth reading. I’ve never read Walking Dead but imagine Kirkman does most of things that recommend it. And most people who read 50s-60s American mainstream comics will place the artists contribution far over the writer.

Gaiman had so many artists, he is the only constant in the Sandman. I never bothered reading Sandman because the artwork is monthly deadline art, even as much as I like Vess, Kieth, Kelley Jones and lots of others. I’d rather read the script (if that became available) than read the rushed art they could manage on the deadline.

On the other hand, if I buy Sandman Overture, I might only look at the pictures.

Marvel did an entire month of wordless comics on all their titles for a month. I think it was called “Nuff Said”. I only read one or two and didn’t remember anything special, but it is interesting that they did that.

Thanks for the links, RAG … the Zak Smith is quite good. Except for the Borges plus … and the shot at Vasari. Give the Italians a break … 90% of what we do as artists comes from the Renaissance, esp. comix.

And the Nino is nice, as almost always with Nino.

You continue to assume that all fans of comics are there because of the writers. I disagree. I frankly don’t think any of these writers are that great, either. The director of a film is roughly equivalent to the artist in comics, both work with a script to bring it to “life.” No one suggests that the writer on a film is the primary creative force, “generous to share credit”. I agree that the sum should be facilitated to be greater than the parts.But that equation is disrupted by overactive egos. A “smoothly functioning sympatico team” does not exist when one claims supremacy over the other. Maybe what is needed is “manners training” for writers.

I think in North America, the story is far more important the art. Manners training for writing is a brilliant idea though … and perhaps, one reason why certain writers may behave arrogantly is their suspicion that drawing is much easier than writing and that hence, they are doing the heavy lifting?

The slacking off in draftsmanship skills may be part of the reason? The over-supply of artists chasing jobs may also lead to such crappy contracts being the norm? Both problems stem from the current art school system?

Noah and Mahendra– I guess beauty wasn’t the most accurate term… even when I look at the work of the artists you mention, there is a sort of heart-swelling, world-is-at-rights feeling I get. Probably because I’ve been academically trained as a artist? It tends to outweigh whatever is going on narratively for me– perhaps a little less so than with Gary Panter, but whatever deskilling he’s doing very transparently reads as the product of someone who knows how to draw.

There is that. Art schools now emphasize “conceptual”/press release blurbing skills over art foundations, to terribluy ill effect. There is also a dearth of actual storytelling skills on display in the art of a lot of comics. Vertigo comics are particularly noted for their bland art, perhaps because the editors expended the bulk of their energies beating the scripts to death before the hapless artists ever see them. And DC as usual outsources their art so it’s most often not exactly a hands-on collaborative process. It would be a mistake to give Kirkman the credit for everything—artists ALWAYS contribute story information as they actualize the work in visual form—- and you can’t reasonably guess what Kirkman did and didn’t suggest…to say the artists don’t have narrative input just displays ignorance of the process of making comics. And, creative credit is shared on the comics and show. It is on the ads for the video game and when people are writing about it that Kirkman is privileged.

The world is always right when it is drawn accurately and well … as Ingres said: drawing is truth.

We should be frying eyeballs and blowing minds with great, over-the-top drawing … what do we have to lose at this point? We’re nearly extinct as a skilled profession.

For what it’s worth, Erik Larson, on Tony Moore being irrelevant in his opinion to Walking Dead:

“It’s not like Superman where there’s a distinctive costume or visual. The zombies aren’t visually distinctive. The people were described in Robert’s script. The idea was Robert’s–the visuals were described–so it’s kind of hard to claim that something Moore brought to the table made it successful.”

http://forums.comicbookresources.com/member.php?725-Erik-Larsen

I don’t actually agree with him… and maybe he’s just kissing the butt of an Image buddy, but it’s interesting to see a writer-artist say artist- artists are interchangeable. I don’t think Larson’s been duped by the way the credit page was written.

The problem you’re bringing up, Pallas, is really something else. It’s the problem of non-illustrators insisting on having the final say on everything visual in a project.

It’s the eternal dilemma: they hire you not for your skills, but despite your skills. This happens in comix, advertising, publication work. There is no solution except to earn such clout in the business that you can out-arrogance your tormentors.

Hence the importance of draftsmanship … you must always be the best illustrator in the room. That comes with drawing skills, nothing else.

Certainly the ante needs to be upped. It is sad that I rarely see a collaborative “commercial” comic I consider to be worth buying. It is most likely the result of this inequity–why would anyone invest much of themselves in something that someone else is going to take the lion’s share of the credit for? Most of what I like and that seems to be moving the form forward is single-author alt-lit indy efforts. I’m not deluded—creative writing is quite hard. I respect it, I just don’t feel that the collaborative artist in comics should have to share less than half the credit for the results. Larsen must want to be the new John Byrne. Why don”t you cite a real artist?

Meh.

For me, it is hard at this point to imagine other (or better) art for Maus. It is its art and it works perfectly for it as far as I’m concerned.

I’m not concerned with concepts such as “draftsmanship.” I am not even sure I can make sense of what it is supposed to mean in the comics context.

Oh, and to answer your question way up, Noah – I’ve read and loved Kyle Baker’s Nat Turner – even a mostly (or totally) wordless comic is still read.

We visual artists have created an art form in which draftsmanship is becoming meaningless … we have drawn ourselves into a corner. Our core skills are becoming optional to the audience.

And artists wonder why they are having such a hard time of it?

I used to read Larsen’s Savage Dragon and I liked it a hell of a lot, it was extremely unpredictable and it does all the things DC and Marvel likes to tell fans they do (that everything that happens will always matter and has consequences); but I went off it because the art got increasingly workmanlike and only did the bare minimum it needed to.

Larsen also got flack for defending McFarlane against Gaiman, but I really don’t know much about that case.

I never would have gave comics a second look if all there was only the alt comics graphic novel style (no offense to them, it just aint my thing). I used to read some comics on hype alone but now if the art doesn’t impress me, I will not read it.

That Larsen quote also reminds me of Mike Ploog once talking about the visual creation of Ghost Rider, who was already described by the writer as a biker with a flaming skull head; he joked “what are you going to do? Give him a moustache?”

I am not saying that the art doesn’t matter or that artists aren’t co-creators, but rather it matters in the context of the story being told, as the art in comics is at least half the story. To worry about draftsmanship (which, again, I am not sure how that is defined or codified) is like complaining that Twain is a bad writer b/c Huck Finn and Jim used “broken” English.

Also, art in some comics is ill served by poor inking or coloring by a different person.

I’m certainly prejudiced in favor of art, but I won’t ever buy a comic for story alone. Likewise, if the art is nicely done but at the service of crap, the thing hasn’t any real value. Which is why so much of Toth’s career and the rest of comics history are such a waste. The only Gaiman things I could read have been drawn by skilled cartoonists—Craig Russell, Chris Bachelo, Jill Thompson come to mind. But Vertigo would often have some pages in a given comic done by one artist, other pages by another…it showed that they considered the artists to be interchangable and expendable. It is where they failed and where Gaiman’s things fall apart to mush. Of course comics are better if both writing and art are done sincerely. So, just as things begin to improve isn’t the moment to start treating artists like shit again.

Robert — that Zak Smith thing has a link to a paper about International Art English — that paper is a hoot!

BTW, James — you might not have noticed this if you don’t pay as much inexplicable attention to their publishing solicitations as I do, but a lot of Marvel books now include the writer’s name in the actual title itself. It’s not just Daredevil; authors, Mark Waid and some other guys who cares who. It’s Daredevil by Mark Waid; authors, Mark Waid and some other dudes who illustrated it for him.

Actually one thing Marvel’s been experimenting in doing in crediting artists as “storytellers”. For example of this issues of Daredevil says in the credit section:

Mark Waid and Chris Samnee

Storytellers

javier Rodriguez

Color art

This is apparently supposed to show greater acknowledgement for the artist and increase their prestige in the medium, or so some fans have told me.

This just in from the Guardian, via the Comics Reporter:

http://www.theguardian.com/science/2013/nov/24/comics-language-neil-cohn-cartoons-grammar?CMP=twt_gu

Comics as language … the article is mostly old news to HU readers … towards the end, the point is made that exposing kids to drawings makes them draw. Disney comix art was the example proferred …

We need an HU reader/parent who is willing to expose their child to nothing but Velaquez and Rubens and Dürer … in 20 years will they be Super Draftsmen?

And will readers of comix even notice?