I wrote a bit back about Cecelia Grant’s novel A Lady Awakened. As I said, I loved it all the way up until the last fifth or so, when everything got resolved happily, causing me to be deeply depressed.

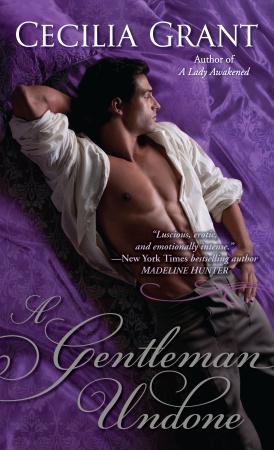

After taking some time to get over my disappointment though, I girded my bits, and read the next two novels in the series: “A Gentleman Undone” and “A Woman Entangled.” Neither was really quite up to A Lady Awakened…until the end, when both were (not coincidentally) less disappointing.

After taking some time to get over my disappointment though, I girded my bits, and read the next two novels in the series: “A Gentleman Undone” and “A Woman Entangled.” Neither was really quite up to A Lady Awakened…until the end, when both were (not coincidentally) less disappointing.

The main difference between books 2 and 3 and book 1 is that 1 is more ambitious. In the first place, the lovers face much more serious difficulties Martha in book 1 has just lost her abusive husband, and needs a child and heir if she is to keep her place, so she hires her neighbor, Mirkwood, to sleep with her. Her husband abused her as well — the book is in many ways a long, painful ode to the powerlessness of women in that age. Moreover, while books 2 and 3 mostly stick to working for the happiness of their couples, book 1 spreads out to include the entire countryside, and the farmers and families for whom, as landowners, Martha and Mirkwood are responsible.

The ambition in book 1 is definitely part of its energy; book 3, deals with two bland social climbers who are pallid nonentities both compared to the courageous, broken, determined Martha, and the social milieu of drawing rooms and society barely registered compared to the multi-class social world of the first book, complete with importunate pig. But ultimately, book 1 buckles beneath its own sweep. I can believe that those two pallid nonentities in book 3 could get together and make each other happy; why shouldn’t they? I can believe that the wounded soldier and the fallen woman in book 2 could heal each other — a little more of a stretch, but not impossible. But that circumstances should fit together to not only extricate Martha from her own predicament, but that Martha and Mirkwood’s love should be so perfect as to spread peace and happiness throughout the hinterlands…it’s just not credible. Romantic love is not the solution to all social ills; two people, no matter how worthy, having good sex and meaningful conversation just is not going to feed the hungry nor (as book 1 suggests) abolish rape and violence.

This is one way, perhaps, in which a fantasy YA romance like Twilight, or The Host or for that matter, Tabico’s insect-sex apocalypse, have an advantage over the regency. the realism of the regency requires some grounding in probabilities; the gestures at social realism interfere with the sweeping fanciful dreams. Fantasy or sci-fi, though, mark their fantasies more clearly as fantasies. Love can save the world — provided it’s vampire love, or love with larva. I also appreciate the horror elements in both Twilight and Adaptation; the sense that, if the personal and sexual were to become social, the social would have to change in ways which would be not just beautiful, but traumatic. The revolution requires blood, of one form or another, or at least a transformation more thoroughgoing, and more potentially disturbing, than just marrying that nice landowner next door.

Though maybe, on the other hand, there is something uncanny and disturbing about regency’s, after all. The end of book 1 (A Lady Awakened), where problems fall away and everyone starts to have their personalities scooped out to be replaced with a sickly sweet happiness; that’s not utterly different form Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Or the way that, certainly by book 3, you know as soon as their introduced who is going to end up with whom, so that the rest of the novel becomes disturbingly like watching watching lifeless mannikins speak and walk and perform like human beings — there’s an uncanny valley charge there as well. If horror can often be read against itself to provide a happy ending for the monster, perhaps romance, too, can be seen not as a triumph of love, but as a beakly mocking, knowing patomime of despair.

Can you imagine yourself bring satisfied with any happy ending in a genre romance novel? I’m asking seriously, not to be difficult. You always know who will be together in the end. Their names are on the back of the book. The plot is always various machinations to get them together. They are always happy and together in the end. Can that story ever be satisfying to you? If bloody revolution is the source of your emotional satisfaction, romance is always going to disappoint.

Sure! I like Bringing Up Baby; I like Say Anything; I like Pride and Prejudice and A Room With a View. I thought the ending of A Gentlemen Undone was fine, as I say here. I think the ending of Twilight and the Host work okay. (I realize you might not categorize all of those as genre romance, but as I’ve said I don’t really like restricting the definition in that way.)

And I’m also kind of thinking about ways in which I could find the ending of a Lady Awakened satisfying, by seeing it as uncanny valley horror. But the main point was that I think putting the burden of sweeping social change on the romance plot doesn’t work well.

Who places that burden on it?

Well, A Lady Awakened places that burden on it by wanting the romance to basically cure all the ills of the surrounding countryside.

I’m not saying, all romance is bad because all romance wants a love affair to create sweeping social change. I’m saying, this particular book wanted to have that happen and it doesn’t really work — and, relatedly, here are other works that want to do it where it seems to fit better.

Interesting, Noah. I see what you’re getting at, of course, but I regard it as the price of admission, the way we justify our fantasy of living in a society built upon such horrible inequality. (The beginning of the Industrial Revolution, people thrown off the land by Enclosure, well before the fledgling industrial proletariat learned how to organize into trade unions: the story is fully, and sadly, told in E.P. Thompson’s THE MAKING OF THE ENGLISH WORKING CLASS.)

Georgette Heyer, who more-or-less invented the Regency romance, had it easier, being a Thatcherite before Thatcher. HER Regency was simply a society of just reward for the worthy and deserved humiliation for strivers. Heyer’s work has many virtues, but I wouldn’t have liked to find myself seated next to Heyer herself at an RWA luncheon.

Whereas the Regency writers I like, admire, and identify with try to square the circle, by trying to imagine a valiant couple both keeping their privilege and sharing it. I wrote about this in a review of a novella collection at https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/656291657: I thought the short form handled the contradictory elements articulating our fantasies more deftly than a full-length novel can.

And I made myself an honest woman in one of my novels, ALMOST A GENTLEMAN, where I have a rather nasty, if honest, character tell my hero that: “We need you, … and your yeoman happily tilling your soil …. A man like you makes such a splendid, chivalrous, knightly sort of . . . of image for England, don’t you know… makes us look less like those money-loving Yanks…”

And of course I was thinking of Mr. Knightley, who is in part the product of a certain self-regarding line of thought current in Jane Austen’s time, the trope of enlightened landowner as contemporary unrecognized nobility (see SUPERINTENDING THE POOR: CHARITABLE LADIES AND PATERNAL LANDLORDS IN BRITISH FICTION, 1770-1860 by Beth Fowkes Tobin.)

As for the pod-people metaphor… back later.

That’s a lovely review.

Just a note that the pod-people metaphor is not exactly mine. I’m kind of stealing from Stephenie Meyer, whose The Host is basically romance told as pod-people sci-fi horror. Meyer is a crappy prose writer and her characterization and plotting are no good, but I think her take on genre is consistently marvelous.

I remember during the conversation about Longbourn, Pam noting that the romance genre’s notion of “reform” is largely symbolic (although the fact that it is even mentioned at all presumes that the novels will push against the status quo in some way). I don’t read Regency novels, but in the romances I do read, particularly those dealing with race and African Americans, I find myself more accepting of what basically amounts to a “gesture” towards society’s ills and the need for the kind of interventions that largely happen outside the world of the story. Context and history matters but I guess what I’m most interested in are how the characters develop in relation to one another, if that makes sense…. In other genres, I’m not satisfied with a gesture. Definitely not in science fiction. Mash-ups make things even more interesting. I think N.K. Jemison’s work is a great example of this.

I like the idea of romance as uncanny valley horror, though. Isn’t that what makes movies like “Pleasantville” so fun?

I think gesturing works better. Sort of interesting that even gesturing rarely happens at all in romcoms. Are there any recent romcoms which even tangentially acknowledge class difference? (Drinking Buddies actually does, subtly and smartly I think, but it doesn’t happen very often.)