Earlier this week Orion Martin wrote a post in which he argued that the X-Men essentially appropriate the experience of the marginalized for the white and middle-class. The X-Men consistently presents itself as a comic about the excluded and discriminated against, but under the guise of preaching tolerance, it actually (as as Neil Shyminsky argues) erases difference. The only marginalization that matters is being a mutant, and every adolescent white boy is a mutant; ergo, adolescent white boys are as oppressed (hell, more oppressed) than anybody. Let us, then, pay attention to their angst exclusively.

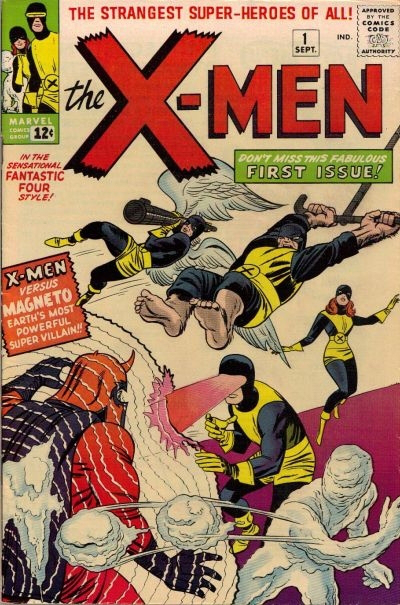

Anyway, I thought I’d test Orion and Shyminsky’s arguments against the original X-Men comic; that’s X-Men #1 by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby from way, way back in 1963. I’d remembered it as being an awful comic, and it is that; one of those Lee/Kirby efforts where proponents of Kirby would be well served by attributing as much of the writing to Stan as possible (and as much of the art too, for that matter; this is not within a mortar shot of being Kirby’s best work.)

Part of why the comic is so crappy is that it matches up with Orion’s thesis so perfectly that it’s painful. We first see the X-Men (Cyclops, Beast, Ice-Man, and Angel) in a palatial, exclusive private school. The first few pages are all cheerful boys’ school high jinks, enlivened only by the student’s obsequious deference to, and competition for the approval of, Xavier. It’s an unbroken collage of fusty preppiness and ostentatious privilege — underlined when Angel mentions off-hand that he’s a representative of “Homo Superior.” Is he referring to his wings or his class status? It’s not clear.

Be that as it may, the plot grinds on, and we hear that a new student is coming: “a most attractive young lady!” as Xavier tells his all-male students, before even communicating her name. Said male students then cluster around the window looking out, making various lewd observations (“A Redhead! Look at that face…and the rest of her!”) We are, in short, insistently positioned with the guys; we and they sexualize her before we even see her. When the X-Men do finally meet the new recruit, they spit out various stale and uncomfortable pick up lines, culminating in Beast trying to kiss her. Thus the first effort at portraying difference in the X-Men comic, the first introduction of someone who is not like the others, results in objectification followed quickly by sexual harassment. (Jean does use her telekinesis to put Beast in his place…but then refers to him sympathetically as “poor dear,” just so we know she’s not really angry or freaked out at having her fellow students trying to fondle her within ten minutes of arriving at her new school.)

>Yet more leering at Jean.

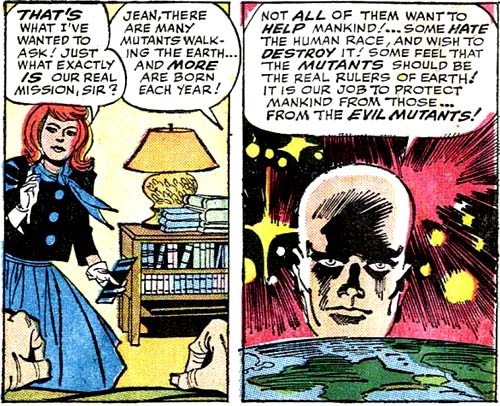

Somewhere in the middle of this edifying display of gender politics, Xavier gives with a quick speech about how normal humans fear mutants (“the human race is not yet ready to accept those with extra powers!”) and so he’s set up his luxurious refuge, where X-boys can leer at X-girls undisturbed by outside interference. He adds, though, that they have a mission to “protect mankind…from the evil mutants!”

Shyminsky points out that the X-Men basically spend all their time attacking other mutants who aren’t sufficiently assimilated; their work is to further marginalize their brothers in the name of a justice of the privileged which is never questioned. That certainly fits this story, where Magneto’s plot involves attacking a US military base and disabling armaments and missiles. Again, the year here is 1963, deep in the cold war. Actual marginalized people at the time and earlier (like, say Paul Robeson or Woody Guthrie) were able to figure out that U.S. military power was used in less than noble ways around the globe, from Cuba to Indonesia to Africa. You’d think that a self-declared Homo Superior with experience of oppression like Magneto might be able to articulate that. But, of course, he doesn’t; he’s just an evil villain whose evilness serves deliberately to emphasize the justness and general awesomeness of the U.S. military.

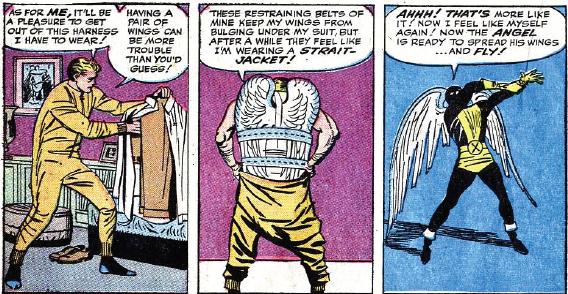

As for the X-Men’s marginalization…it seems easily doffed. The military guys aren’t scared of them, but welcome their help. The most uncomfortable scene of difference we get is a three panel sequence in which Angel changes out of his street clothes, revealing that he trusses his wings up behind him to keep them out of sight. “After a while they feel like I’m wearing a straight jacket!” he says. But no one ever questions why he has to bother to tie up his wings, or make himself so uncomfortable for the convenience of people who (supposedly) hate him. In fact, the sequence seem much less interested in Angel’s discomfort than in the ingenuity of the disguise.

Shyminsky notes that this fascination with, and eager embrace of, assimilation can be linked to the biography of Stanley Lieber and Jacob Kurtzberg, who changed their named to Stan Lee and Jack Kirby in order to be taken, like Angel, for normal humans. There’s a poignance there, perhaps, in Angel’s discomfort — Lieber and Kurtzberg’s new names may have pinched them a little at times too. But they nonetheless persevered in tightening that truss, which, in this comic at least, consisted not merely of new names, but of what can only be called a servile, deeply dishonorable acquiescence in hierarchical norms, casual misogyny, and imperialist fantasies. I hated this comic already, but as a Jew reading it as a parable of Jewish assimilation, it makes me actually nauseous. James Baldwin says that black people hate Jews (when they do hate Jews) not because they’re Jews, but because they’re white, and this seems like a fairly withering illustration of what he was talking about; a sad account of how my people (not all my people always, of course, but some of my people too often) kick those further down the food chain in a craven effort to look like, act like, and be the ones in charge. Xavier isn’t Martin Luther King; he’s a neo-con, and/or Michael Bloomberg, so charmed by whiteness that he devotes his existence to telepathic racial profiling.

So, yeah; this is not just a badly written comic, but an actively evil one. Other X-Men stories may be better — and indeed, they’d almost have to be. But at its inception, the title was a stupid, craven, explicitly sexist and implicitly racist piece of shit.

If they didn’t want to get attacked, maybe they should have named themselves something other than “The Brotherhood of Evil Mutants”. Just sayin’.

You’re forgetting that the minority/alienation angle was discovered later. The X-Men’s debut was a rushed, “us too” lift from Doom Patrol and a variation on the Fantastic Four template. The mutant gimmick functions solely as an efficient explanation for putting a bunch of superpowered characters in action.

No, that doesn’t wash, Tapper. Look at the panel above with Professor X’s floating head, if you would. He’s making a claim for marginalization and minority/alienation right there. The assimilation theme is pushed hard too (see Angel and his wings.)

Certainly it’s a rushed out hack job. But it’s a rushed out hack job that endorses U.S. imperialism, sexual harassment, and assimilation in the name of kicking fellow marginalized peoples. That’s a lot of vile ideology in a short story, even on deadline.

I bet they still would have had problems if they called themselves the Black Panthers. Or so history suggests, anyway.

Nice work, Noah.

I think you hit on something I have been saying for a while about the racial and sexual other in superhero comics – they have to prove their worthiness through violence against and/or policing of others of their kind. The X-Men (esp. early X-men, but definitely into Claremont’s classic run) just reinforces this and is all the more egregious by white-washing the difference to begin with.

Xavier could only be MLK if MLK had armed young black soldiers that went into black communities to violently combat the threats to black middle-class respectability that he cared about above all – in other words, it doesn’t jibe with MLK both ideologically and in practicality.

Osvaldo, that’s a really good point. X-Men makes it particularly evident, through its use of an ensemble cast of many superheroes and supervillains. But this self-policing, masochism and assimilation seems like a foundational part of the genre. And one that I think comics is congratulated for– the ‘nobility’ of a guardian who loses his ability to ‘be one’ with the society he’s protecting. Or, how pure these fantasies are, coming from the brains of marginalized Jewish teenagers at the turn of the century.

There’s convincing evidence for superheroes stemming out of the stage and dime-novel melodramas (Alex Buchet’s work, for example.) Melodrama, when not fully occupied with sawmills and speeding trains, navigates a weird zone between comedy and tragedy– an unreconcilable schism is presented between the protagonist and society, which the narrative itself can’t solve, and so absolves it through a unifying trauma which stitches everyone back together. This is often the trauma of near death to a female body, the heroine lies freezing on an ice floe speeding towards a waterfall, etc. etc. Once she is rescued, it magically doesn’t matter that she’s still a fallen women, when the society that embraces her hasn’t come close to amending their value system.

To wind back to the central concept– while I’ve heard ‘secret identities,’ and ‘serialized thrills’ spouted as reasons for superhero comics to be melodramas, I’ve never heard them discussed as assimilationist fantasies. But it fits really well.

And melodrama is important! Probably no other narrative mode has had a great as influence on society and politics in the last few centuries, and melodrama increasingly pervades political and campaign imagery. Melodramas are ‘people-movers,’ and make whatever story they’re conveying especially sticky.

I don’t usually get much out of semi-“academic” dissections of stupid superhero comics from the 60s/70s (see Shyminsky) but I guess there’s some worth in pointing out just how bad those comics are. Mind you the splash pages from the X-Men comics of that era go for tens of thousands of dollars (if not >100K).

Oh, and things haven’t actually moved that far forward since the 60s. Everyone’s beloved superhero Joe Schmoe is also somewhat enamored with the military establishment. I guess Domingos is right to hate all those comics.

Like the mid-2000’s meme said: Magneto Was Right.

I think the core of this issue is the mis-identification of one’s own struggle as equal to the struggle of another. When privileged writers try to weave race into the stories, they use their own experiences as a model for oppression, and readers from similar backgrounds follow the same logic.

Kailyn,

When you’re talking about melodrama and conclusions, does that change in series where the characters never die/age? It reminds me of a quote form an article on the AV Club,

“No matter how hard Bruce Wayne tries, he will never completely win the war against evil as long as Batman continues to make money for his corporate overlords, and over the past 74 years, he’s never seen rest, just reboots and resurrections. It’s part of the nature of superheroes; the popular ones are forever young and motivated while the others age, give up, and eventually disappear into comic book limbo.”

http://www.avclub.com/article/ibatman-incorporated-i13-concludes-grant-morrisons-101112

“this is not just a badly written comic, but an actively evil one”

Hesitant to dip my toes into this one, but…this is an over-the-top reaction, even by your standards, Noah. I’m on board with a lot of what’s been said over at Orion’s post (both in the post and in comments), but I was going to say something much like what Tapper said about these early comics.

Lee’s claims that it was always a metaphor for civil rights are FOS; that came later. At its inception, it was an attempt to recreate the success of Fantastic Four. Mutants, at this stage, are not yet “hated and feared” or what-have-you; they’re not at all marginalised, if I remember the comics basically right.

Xavier’s floating head is saying that we mutants are so f*ing powerful that we need to restrain ourselves from ruling humanity — it’s one ubermensch protecting the herd from another ubermensch, just out of the maganimity that overflows from the true ubermensch; it’s not one marginalised community doing down other members of the community lest they rock the boat. And Angel’s “passing” is just a variation on the superhero trope of the secret identity — again, the metaphor for passing as white wouldn’t come until later. (I’m thinking Claremont and Byrne with Nightcrawler?)

…Just to be clear, I totally endorse ideological critiques of the minority metaphor in later X-Men comics. I just think it doesn’t work here. There’s still loads to ideologically critique here, e.g. that sexism! (At least it’s not as bad as FF, where Lee’s scripts several times disempower Invisible “Girl”, overriding Kirby’s plot/art)

Yeah, I am very much not convinced. Superhero secret identity is always about assimilation, it seems like to me; Siegel and Shuster built that in pretty openly, so saying, “it’s just like any other superhero secret identity” underlines and generalizes the point about assimilation, it doesn’t contradict it. And I just realized I didn’t reprint it, but Xavier says a few panels before that that he was persecuted and marginalized as a kid; he states very clearly that he was marginalized for being a mutant — and then goes immediately on to say he’s going to track down other mutants.

You’re also not dealing with the enthusiastic pro-imperialism, which links up with the marginalization. I’ll stand by calling it an evil comic. (And I don’t think that’s particularly over the top. Evil’s not that uncommon; folks just like to think it is.)

Here’s what Xavier says:

“But when I was young, normal people feared me, distrusted me! I realized the human race is not yet ready to accept those with extra powers! So I decided to build a haven…a school for X-Men! Here we say, unsuspected by normal humans, as we learn to use our powers for the benefit of mankind to help those who would distrust us if they knew of our existence!”

That seems pretty straightforward. I don’t think the argument that the marginalization metaphor came in later holds up.

“this is not just a badly written comic, but an actively evil one”

Jones, when it comes to Noah I usual just cut about 20% of the vitriol off the top as rhetorical hyperbole. ;)

Harumph.

I really don’t think it’s hyperbole. It’s an ugly comic. Reading it really made me angry (as opposed to the Claremont run I was just flipping through, which is solidly mediocre.)

Yeah, I stand corrected — it’s not over-the-top by your standards. I’d forgotten that by “evil” you mean “morally wrong”, but in ALL CAPS.

“But when I was young, normal people feared me, distrusted me! I realized the human race is not yet ready to accept those with extra powers!”

It’s true that Lee throws this in there – but this element is in Spider-Man from the start, too (and for that matter, it’s in the FF in any Thing-centered story). It’s a theme that Lee reused over and over again because he knew it played well with an adolescent audience that felt marginalized and alienated. The idea of mutants as an oppressed people, with Xavier and Magneto taking different diametrically opposed stances on how to achieve liberation, really only begins to cohere at all during the Claremont era; during the Silver Age, they spend most of their time running around fighting aliens and dinosaurs.

Now, once the X-Men really does become a self-conscious metaphor for a struggle for liberation, I agree with what you’re generally laying out here. Xavier is a creepy sell-out and an establishment tool, a rich, white, successful man who passes as “normal” in order to better ingratiate himself with that establishment, while he trains young and naive students to hunt down and capture those of his people who are trying to fight their oppression. But the offensiveness of these characters really only becomes apparent once the series is actively claiming to be a metaphor for oppression: it’s anachronistic to take the early 60s comics, which as yet had no such pretensions, and attempt to directly draw such conclusions from them.

It is true that X-Men #1 is generally terrible, though – as well as sexist, and just mindlessly imperialist, as was Marvel in general at the time (the Fantastic Four launch their rocket prematurely in their first issue because they have to beat the reds; Spider-Man’s first recurring villain is the Chameleon, a commie spy; Iron Man spends most of his first decade or so fighting official enemies of the United States, including the painfully racist Fu Manchu analogue the Mandarin).

The fact that Lee uses themes of discrimination and marginalization in other comics…why does that mean that themes of discrimination and marginalization can’t be in this one? And sure, those themes tie into adolescence. But, again, that doesn’t mean they don’t also resonate with the Jewish experience.

Xavier says in this comic that he is a discriminated minority. It’s not just “thrown in”; it’s the explanation for his mission, and presented as the basis for his identity. He goes on to say that his mission is to attack other discriminated minorities. Further, there are themes of assimilation throughout the comic (not subtle ones, either.) It’s just not clear to me what else has to happen here. I mean, the argument seems to boil down to, “there is more of this later on, therefore it isn’t happening here.” Which, again, doesn’t seem to make much sense.

Jones, I’m not sure what the difference is supposed to be between evil and morally wrong, precisely. This comic seems to me to demonize others, normalize sexual harassment, and encourage imperialism and cold war violence. That seems evil to me.

Oh, re the Thing; The Thing is one of the characters who is most clearly Jewish. So I think the themes of alienation with him absolutely link up with themes of discrimation and marginalization in a Jewish context. (I think the way they’re handled with him are generally more thoughtful than the way they’re handled here.)

Noah, I think you’re reading X-Men #1 not in the context in which it was produced. Again, look at the X-Men stories that follow, which are not, as one would expect from reading the X-Men comics of the 80s and 90s, about the X-Men struggling against mutant persecution, but are largely about the X-Men fighting alien invaders, having bizarre adventures with Ka-Zar in the Savage Land, etc. It’s not until Claremont comes along that Magneto becomes a militant fighter for mutant liberation; in the Silver Age he’s much more a generic world-conquering supervillain.

You’re reading back into this particular comic a theme that was developed much later by other writers – notably Claremont and Byrne. And those later comics, which do explicitly develop the idea that mutants are oppressed and that the X-Men represent the “right” way to fight oppression while Magneto represents the “wrong” way, are the correct target of the criticism you’re trying to make here. But aimed at the Lee/Kirby X-Men – a generic, third-tier Silver Age comic which even its creators lost interest in less than a dozen issues in – those criticisms are anachronistic.

I’m not reading back. I’m reading what they wrote.I’ve cited specific moments in this comic. The only thing you’ve done to explain those away is to say that other people also used those themes. I don’t find that a convincing argument.

The theme of marginalization in the original X-Men is tied to superior abilities. One of the first scenes that resemble the anti-mutant hatred that defines the later version is when Magneto’s lackey Toad enters a marathon in disguise and wins by hopping his way to the finish line. As the crowd rises up, Angel flies by thinking, “Gee, Professor X was right when he said that people will hate us when they learn of our existence.” But this isn’t the mutant-hating mob familiar from the Claremont X-Men; the crowd is offended because they think the runner won the contest by cheating and using fakery. The existence of mutants is a secret, and the point is that mutants who attempt to compete in human society will encounter hostility because of the edge given them by their powers. Similarly, the “X” in the title stands for “eX-tra power,” not the X-Gene or Professor X’s name as later explained, and the term “homo superior” (derived from the mutant genre in science fiction) is already in use. The conflict is between Magneto as a straight-up fascist who believes that mutants’ superiority gives them the right to rule, while Professor X envisions mutants and humans working together for progress. Magneto stages attacks and demonstrations of superiority while the X-Men win popular devotion by acting as masked heroes. The concept is generally agreed to derive from the science fiction novel Children of the Atom, about a secret school for children with enhanced intelligence (derived from their parents’ exposure to radiation, the same as Professor X describes) who contribute anonymously to society. The comic was originally titled “The Mutants,” but the publisher felt the term was too arcane. The mutant genre in science fiction (see also Odd John, Slan) is deeply concerned with alienation and marginalization, but this is not the conflation with the civil rights movement that was later applied to the X-Men; rather, it’s tied to the self-conception of the nerd who is alienated for his superior mental prowess. The contention in the original X-Men is over what the characters should do with their superior abilities, not how they should respond to a universal experience of oppression.

“rather, it’s tied to the self-conception of the nerd who is alienated for his superior mental prowess”

The idea that this has nothing to do with discussions of Jewish identity seems willfully blind to me.

I think that it’s certainly about nerds. It’s also about linking nerds to other discriminated groups (by making their discrimination biologicaly, for example.)

I think your interpretation is reasonable. I also don’t think it actually negates mine, or contradicts it.

The connection of these narratives to racial discrimination is not easy or one-for-one. To discuss it you have to deal with the larger idea of the superman, and get into the ways Jewish comic book creators took up the concept in the 20th century and the ways, if any, they were putting it in dialogue with Nietzsche and the Nazis. It’s an interesting phenomenon but its study, I think, has been distorted by the kind of retrospective over-intellectualization that comic book apologists employ to attribute more complex literary statements to their medium than were really present. The problem with conflating the myth of a race of beings with superior abilities with the experience of racism is that such ideas are more easily placed at the service of racism.

The notion of the Jews possessing nigh-supernatural powers is cherished by conspiracy theorists, not the Jewish tradition.

Magneto’s spouting easily recognizable Nazi ideology from his first appearance (he’s not the Holocaust survivor he would later become) makes Professor X’s mission of opposing him something other than the subjugation of his own minority you paint it as.

The link between nerds and Jews is of quite long standing, and is often perpetuated by Jews (Woody Allen being the most obvious example.)

“The problem with conflating the myth of a race of beings with superior abilities with the experience of racism is that such ideas are more easily placed at the service of racism.”

Yep, and in various ways. That’s the point of the piece.

What moose n squirrel said.

I guess I’m done. I don’t really see any new arguments being made, nor any that make me change my mind about the comic. But thanks for commenting all; it’s been an interesting discussion.

Yes, but the mutant genre in novels like Children of the Atom, Odd John, and Slan appeals to the nerd who concludes that he was bullied because of jealousy for his superior intelligence (and not other social deficits.) There’s an ugliness to that idea. And as I said, the notion of Jews possessing superior talents has been more enthusiastically disseminated by conspiracy theorists than Jews themselves.

From Children of the Atom:

‘Most kids with IQ’s of over 160 have to adjust on a lower level in order to live in this world at all. It always seemed to me a great waste. And these — what will they be like when they grow up?… The bright child has all too often grown up to be a queer, maladjusted, unhappy adult. Or else he has thrown away half of his intelligence in order to adjust and be happy and get along as a social being. These children are bright beyond anything the world has ever known… Think of such intelligence combined with a lust for power, a selfish greed, or an overwhelming sense of superiority so that all other people, of average intelligence or a little more, would seem as worthless as . . . as Yahoos.’

…’It’s an awful responsibility,’ said Foxwell. ‘And did you hear those kids talking about heredity, last week?’

‘Yes,’ said Peter.

‘They’ll be so far above us when they are adult,’ moaned Dr. Foxwell, ‘I swear I’m afraid of it.’

‘Timothy Paul has the answer, I think. A school, where they can work together under our direction, and have as much freedom as they can stand…’

http://www.redjacketpress.com/books/children_of_the_atom.html

Yes, I immediately thought of A.E. van Vogt’s Slan too when I read this thread. Interestingly enough, Slan formed the partial basis for Keiko Takemiya’s Toward the Terra (???) comic book series, (also adapted into an animated film by Toei), but with a twist: the superior mutants all had various handicaps, (weakness, blindness, missing limbs, etc.) though the protagonist was extra special since he was largely free of defects. I hadn’t known about Children of the Atom though, which clearly seems to have provided inspiration to the X-Men.

Argh; said I’d stop,and have failed. Oh well.

I think the link to the Nazis is certainly there and important. I think it matters too that mutants are defined as despised, and then evil mutants are tied into eugenics — and then conflated with anti-Cold War policies. I don’t think that undercuts what I say about minorities hunting minorities. In terms of Jews, it seems like there’s a pretty straightforward line between identifying as a minority, identifying with the American power structure, and casting other minorities as potentially subversive Nazis. The fact that the U.S. was on the right side in WW II has certainly been used to frame later U.S. actions as honorable and just, even when they involve prejudice and discrimination (“Islamofascism.”)

In terms of who frames Jews as powerful and secretive; I’d say that the X-Men here plays into the stereotypes to some extent, while turning them around so that the powerful minority/Jew is the trustworthy good guy.

>> I think you’re reading X-Men #1 not in the context in which it was produced

I think it is really weird to say this. Wasn’t it produced in a context in which the American civil rights movement had been going on as a very visible struggle in mainstream American media for at least 8 or 9 years? And hadn’t lots of people of Jewish heritage working as allies in that struggle?

Regardless of what Lee and Kirby intended or even connections a lot of readers saw at the time, the context is there and a valid way to think about the comic. It is far from “over-intellectualization” as jmoore says or being an “apologist” for those comics. I thought at this point that is kind of self-evident.

Noah says, “In terms of Jews, it seems like there’s a pretty straightforward line between identifying as a minority, identifying with the American power structure, and casting other minorities as potentially subversive Nazis… In terms of who frames Jews as powerful and secretive; I’d say that the X-Men here plays into the stereotypes to some extent, while turning them around so that the powerful minority/Jew is the trustworthy good guy.”

But the X-Men don’t sell out other minorities, or even their own. Your narrative would be more applicable if they were portrayed as capturing subversives for the government. What they do is defend against overt attacks and talent-hunt mutants for their own secret team before Magneto’s can claim them. This is part of the never-ending drama of superbeings in which one side wants to rule and the other wants to help. When Lee and Kirby picked up the trope of a mutant super-race, they immediately perceived the connection to Nazism and gave their villains a racist ideology. This doesn’t mean they were speaking in code about their own ethnicity, or selling anyone out. If they were pushing the idea of a benevolent conspiracy between Jews and the military/industrial complex while demonizing other minorities, then why does Magneto belong to the same race as the heroes? (Or is he the Arabs, still “Semites”?) Isn’t it more likely that they were not concerned with defining Jewishness on any level but simply trafficking in the most universal themes of power and alienation?

“Isn’t it more likely that they were not concerned with defining Jewishness on any level but simply trafficking in the most universal themes of power and alienation?”

I doubt they consciously were trying to define judaism. But there are lots of assimilationist themes there, and themes around marginalization.

And why are you assuming that themes of power and alienation are more universal than themes of marginalization and assimilation, exactly? Saying, “this is about power and alienation” is still a subtextual reading; you’re still interpolating. And, in fact, I do think it’s about power and alienation. We don’t disagree about that.

Magneto is a minority failing to assimilate. The X-Men are minorities who assimilate. You can see it as being a warning to some Jews, or as being a “we’re the good minority, not like them” kind of thing; I believe it works either way.

In terms of picking up Nazi ideology…when you pick that up, and then suggest that folks opposing the US military cold war hegemony are ipso facto Nazis, and then further suggest that the people engaged in that opposition are persecuted minorities — that has a meaning, especially, as Osvaldo says, in a context where the civil rights struggle was very much underway. I’m sure Lee and Kirby didn’t think about it too hard, just like they didn’t think about the casual sexism too hard. Nonetheless, they created a persecuted minority bent on assimilation which fights other minorities in the name of cold war imperialism. That’s the story they’ve told us. The fact that the people they’ve designated as “bad guys” in the story act like bad guys is a function of propaganda. You seem to be saying, Lee and Kirby could not possibly be so stupid as to make a minority a Nazi and treat that person as evil. But people are that stupid with some frequency; I see nothing to suggest that Lee and Kirby were incapable of it.

Re: Vitriol

When The White Ribbon came out a few years ago, this German critic made the point that Michael Haneke is mostly doing pretty much what he seems to criticise in his films – his method of directing is as totalitarian and unfree as the society he’s portraying, leaving the audience no choice but to conform to Haneke’s view and interpretation.

And it’s this kind of double standard I find a bit depressing about some pieces on HU as well. You’re addressing important issues like racism, sexism etc. but you just can’t do it without employing this irrational and hateful language (“evil”, “piece of shit”). I find it somewhat contradictory to argue against prejudice and hate in this hateful manner. I very much appreciate some of the well written, thoughtful articles on here, but these over-the-top rhetorics really put me off : (

To adapt an old point, when the subtext in superhero comics becomes the main thing to discuss about them it’s probably time to read something else.

“employing this irrational and hateful language”

There’s nothing irrational or particularly hateful about saying that a comic which is an evil piece of shit is an evil piece of shit. I’m arguing against a particular ideology, not against a particular tone. I like lots of art which is violent and uses extreme imagery (metal, for example.) If you don’t like that kind of thing, that’s your lookout, but the issue is aesthetic difference, not inconsistency on my part.

Joe, I’m not sure why writing about subtext is a problem. I read that X-Men comic because people were talking about it here. And I don’t for that matter think the issues I’m talking about (sexism, assimilation, imperialism) are particularly buried. The idea that subtext and text can be easily separated for any kind of art seems kind of silly.

Thanks for your reply, Noah. What I meant was as soon as you use religious categories like “evil”, the debate is already over – then it’s all either-with-me-or-against-me, burn the witch etc.

Also there’s a difference between extreme and violent art and extreme and violent criticism, wouldn’t you agree? I can certainly see the benefits of extreme and violent art (I would say some of Haneke’s disturbing films can make people think and I appreciate his work a lot; also there’s nothing wrong with crazy rock music), but I don’t really know how extreme and violent criticism would help create an open, worthwhile discourse.

I just feel more people might listen to more constructive criticism. But maybe that’s just me.

I think criticism and art aren’t mutually exclusive categories. And I’m certainly not interested in providing constructive criticism here; Lee and Kirby aren’t making comics any more, so I doubt they’d read this and say, well, we’re going to change our ways.

I think calling them as you see them is worthwhile, in general. I think this comic is an evil piece of shit; reading it really depressed me and pissed me off. I could pretend otherwise, but I think that would be less honest.

I also think that the call for moderation can itself be a kind of violence. Or at least, I don’t see it as rational or balanced to say, “you can’t call an evil piece of shit an evil piece of shit.” Tone policing is policing. It’s not always bad, but it’s definitely implicated in power. The most worthwhile discussions aren’t necessarily those in which everyone feels comfortable, not least because there aren’t going to be any discussions in which everyone feels comfortable.

haha well if you feel I’m trying to “police” you I’m so sorry. Still I would like to answer, if that’s okay.

“call an evil piece of shit an evil piece of shit”

hmm … so how about calling a homewrecker a homewrecker (just another random example from a recent Lee/Kirby debate elsewhere)? Or why can’t I call a faggot a faggot then, because “calling them as you see them is worthwhile, in general”?

Of course I didn’t mean critics should help (dead) creators with “constructive criticism” – as you can guess (since I already said so) I meant being constructive in an open discourse that people would want to engage with instead of constantly having to deal with all these silly polemics.

Maybe I’m taking this too serious here, or maybe HU actually is criticism as art (as you suggest) but I just wanted to let you know how off-putting this hateful vibe here can be sometimes. Didn’t some HU writer(s) complain somewhere a while ago how HU isn’t being respected and taken seriously enough etc.? Thought this could be part of the reason maybe.

I think there’s a pretty substantial difference between prejudiced slurs and saying that a comic is an evil piece of shit. The first is not calling it as you see it; it’s bigotry. Insulting a comic and insulting a discriminated group using hateful stereotypes are really not the same thing. At all. Comparing them is really not thoughtful. I am here doing as you asked, and keeping my rhetoric relatively mild.

I think there are various reasons that some people sometimes don’t cotton to HU. I doubt it’s the rhetoric per se; TCJ has printed plenty of things that are as inflammatory as anything I’ve ever said. The issue tends to be the target of negative reviews, however phrased, rather than their existence.

Anyway, I’m not so worried about putting people off. I mean, I’d rather everyone loved HU and my own writing, but if doing that means that I can’t say on my own blog a comic which is an evil piece of shit is an evil piece of shit, then I don’t think it’s really worth the candle.

OK thanks for keeping your rhetorics mild here then, I’ll consider this a success … Let’s just see where HU is going, as I said I still enjoy some of the writing on here and despite the vitriol I’d probably still miss this site if it was gone.

Well, I don’t think we’re going anywhere! No plans to at the moment anyway.

I think this conversation is over, but since I’ve only just discovered it…

It’s totally worth pointing out that Stan Lee hadn’t really developed the political angle, yet. The alienation/acceptance angle here is almost totally indistinguishable from the one he was using in Spider-man. When Xavier talks about mutants, the language isn’t quite right – in isolation, it sounds like he’s describing The Ubermensch, not a racial minority.

That said, the first issue certainly doesn’t contradict the later narrative – I mean, aside from the hokey and shockingly casual sexism – so it also seems fair to look at how well it fits. And it introduces the whole Xavier-Magneto and good-evil mutant dynamic that would define series, which means that can’t be totally out-of-step with what would follow.

Pingback: 2013: Reviewing The Year It Wasn’t | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: Grant Morrison’s Doom Patrol: The Craziest Superhero Story Ever Told | My Website

Pingback: Ms Marvel is a progressive superhero, but latest story arc is a step back on race – The Guardian | Best Babytoy Store

Pingback: Ms Marvel is a progressive superhero, but latest story arc is a step back on race | ComicsClub.in

Thanks for sharing such a good thought, paragraph is pleasant, thats why i have read

it completely

A vicious spambot brought my attention to this old post, and I felt like commenting a bit:

From what I see, it looks like the sexual objectation in this story is a classic comic book trope where the men goes absolutely batshit over a girl for comedic effect. Here is another example (from a ‘Marine’ story by François Corteggiani.)

http://s33.postimg.org/5heo881sf/marina_fran_ois_corteggiani.jpg

I hope you can follow despite the danish language. Anyway, despite the obvious objectification – both Tifia and the little dog just gazes at her and says waouw, and we still don’t know her name – despite this, the readers gaze are directed at the men, not the woman. It is mostly about putting the male gaze on display.

The notorious botanical garden scene from BATMAN AND ROBIN leans against the same trope:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sUgUMY-C7MY

I’m not trying to disprove that X-MEN #1 is sexist. But I think this type of stylized, over-the-top display of the male gaze is a lot more clever than a lot of much later examples of sexism in comics. You know, panels or front pages where the heroine just stand and pose for the viewers, or superheroine uniforms solely designed to look sexy.

Oh, grow up, everybody.

Here’s a school full of healthy teenage boys who suddenly encounter a pretty girl of their age.

How the Hell did you think they’d react?