I’ve just finished reading the Vertigo (DC Comics) compilation of Fábio Moon and Gabriel Bá’s Daytripper, originally published in Brazil in 2010 as a 10-issue comic series. It is visually lush—expertly drawn and featuring a sensuous color palette by Dave Stewart (lettering by Sean Konot) — and attempts to ask good questions about the different routes a life can take, including the potential termination of these routes via depictions of the death of the protagonist, Brás, at key points in his life (page 28, 32, 41…). This conceit allows Moon and Bá to explore the “killing off” of a character’s development, without killing off the character himself, and it raises compelling questions about the places we do or do not find ourselves, the people we choose to embrace or dismiss, the work we choose to pursue or abandon.

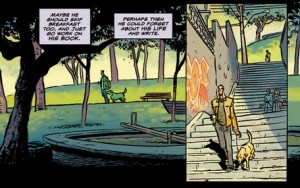

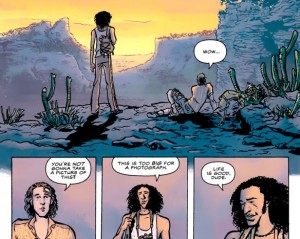

My issue with the work, beautiful and promising as it is, concerns the textual, not the visual, elements. Since I actually weight the visual more heavily in graphic works, I try to avoid treating comics as standard text narratives, since this is nearly always a reduction of the comic. For this post, however, I am going to set the images aside, as I find the panels visually expressive, dense (in the best sense), and superior to that of many other comic works. This excellence, however, sharpens my disappointment in the verbal elements of Daytripper, which had the potential to be a complex and clever meditation on mortality, agency, and human interconnectivity. If the assertions of the narrator and the characters were as arresting as the images, we’d have a remarkable work here.

My chief complaint is this: if you want to take on that ever-present, usually repressed, incessantly itchy problem that we carry with us at all times –I am going to die. I am going to die? I am going to die!—then it seems important to explore it with something more than just seize-the-day, marry-the-girl-already platitudes. Okay, yes, I’m feeling an extra dose of crotchetiness about the marriage and reproduction imperative—really, must everyone partner for life and procreate? Must everyone dutifully replicate himself/herself and augment our bloated population? More pointedly, do those of us who resist or fail to tick these life boxes (married w/children) have no essential purpose in life? Is mating and reproducing essential to being alive, being an adult, creating a life of value? I’m not really sure what’s compelling this fierce trend, but it seems like this basic aspect of our animal life has become the telos of every recent essay, film, and narrative and advertisement I come across (okay, being a little hyperbolic here, but still), and can even be seen in odd ways, for example, the overwhelmingly large number of (sub)genres in the “movies about marriage” Netflix category, which is more than double the total of the second-largest category, “movies about royalty” (see Alexis Madrigal’s fascinating recent article in The Atlantic, “How Netflix Reverse Engineered Hollywood”).

Daytripper purports to be “deep.” It reveals—effectively, I’d add—nuances about its protagonist’s Oedipal struggles against a famous father, the melancholia of youth, the attractiveness of risk, the pull of desire, yet when it opines on life or on death, it offers nothing more than received ideas. Here’s an early example: “Then Brás woke up and realized that when you turn that corner, that future you have written and wished for is not always there waiting for you. In fact, it usually isn’t at all what you expected…. Around the corner there is just another big annoying question mark. It’s called life (35).” A little while later, Brás—in love—calls up a nugget of his father’s wisdom: “…[H]e remembers what his father had been saying all these years—and it all made sense (78).” Ahh, splendid. This ought to be good. Brás’ father is a writer, a major novelist who is feted, annually, at a literary gala held in his honor. Brás is also a writer, albeit one of lengthy obituaries at the moment. A writer reflecting on a writing father’s wisdom: certainly, there will be pith. Here’s what follows: “The moment that won’t fade. The moment we all search for. The moment that he found or that found him. Inside he knew. It felt right, and he knew. She was the woman he was going to spend the rest of his life with (78).” Thump.

As Brás dies in various dead-ends, he also ages, coming ever closer to a fulfilling existence—yep, as a husband, and a father—culminating in a clever time-out-of-time depiction of father-son rapprochement: a letter written by his dying father on the eve of Brás’ child’s birth is not received at its intended time, but, instead, years later when Brás himself is an old man diagnosed with a terminal condition (reminding me vaguely of Lacan’s conclusion in his seminar on Poe’s “The Purloined Letter” that a letter always reaches its destination).So, the circumstances are interesting: Brás is now old, it has been many years since the letter was written. What will it say? What does the great man say to the son? This:

Dear Son,

You’re holding this letter now because this is the most important day of your life. You’re about to have your first child. That means the life you’ve built with such effort, that you’ve conquered, that you’ve earned, has finally reached the point where it no longer belongs to you. This baby is the new master of your life. He is the sole reason for your existence…. You’ll surrender your life to him, give him your heart and soul because you want him to be strong…to be brave enough to make all his decisions without you. So when he finally grows older, he won’t need you. That’s becauseyou know one day you won’t be there for him anymore. Only when youaccept that one day you’ll die can you let go…and make the best out of life. And that’s the big secret. That’s the miracle. (242-243)

Sigh. So he writes, unknowingly confirming the life Brás has chosen to lead. All is well, we’re made to believe; Brás has extended his existence properly, and though ever flirting with death (self-inflicted or not), has managed not to succumb. I’m simplifying a bit; the text as a whole challenges some of these platitudes, even—if I am generous—twisting them ironically at points. But it all seems to add up to the usual counsel: young man, put away your toys, your dreams, your wishes for an exciting “future,” and accept the natural order of things. Take up your proper position as an adult (who will die, and knows he will die), a father whose child, whose son, no longer needs him. This is definitely coded male, but is as restrictive as any discourse that casts woman as limited to her reproductive function. Is this the message of the old to the young? Join us, become like us, young men and women, as soon as possible. We have given over our lives to the next generation, and you must do the same. Even if I step out of my nulliparous state and imagine myself a parent hearing this message, I am equally chagrined. Are we solely here to continue the species?

If Moon and Bá want to explore the question of death and our business here in life, it seems to me that they should push harder, tunnel further, scrape away the expected aspects of life (you will find a career, you will find a life mate, you will engender more life) and source their unique individual essences – the mind each has been given (and the fact that they are twins makes this an even more interesting potential gleaning), the one time combination of genes, experience, thoughts, sensations and feelings that animate Fábio and Gabriel and could imbue characters created by them (I know, I know; I’m nearly committing the intentional fallacy). There are millions of husbands and fathers out there; I don’t want to hear their general resumes distilled down to Brás as everyman. I want Brás to startle me with his insights, as the eponymous protagonist of David Mazzucchelli’s Asterios Polyp does when reflecting on memory, or as Mark C. Taylor does in his recent philosophical meditation on mortality, Field Notes from Elsewhere: Reflections on Dying and Living (Columbia UP, 2009).

Adrielle, way to get into the HU spirit by trashing a “beloved” comic! (Sorry, I couldn’t resist.) While your complaint about Daytripper isn’t my own, I recognize this frustration you describe; it sounds somewhat similar to when I take my daughter to see the latest 3D animated film, especially the ones aimed at girls, and all I can think is, again? more of this? Tell some different goddamn stories! And it hurts more when the graphics are so achingly beautiful, all that wasted potential, and every reviewer tells you that it is great (i.e. “Frozen”).

Daytripper claims to ask big questions – I can see how you would be disappointed when it also tries to answer those questions (via the father’s letter) rather than letting readers struggle with them on their own. I’m curious about how you mention that the visuals sharpen your disappointment, rather than add nuance to plot points that you’ve encountered a million times before. Do you think the fact that you feel you can set the images aside maybe says something too? My general impression of the comic is that its unique construction is part of the reason why it earned so much acclaim. When you isolate the images and design features from a lot of comics, their stories can sound pretty flat. (Not that this excuses bad or unsatisfying storytelling.)

I haven’t seen this comic…but I can’t say the art in the post thrills me. It looks competent enough, but that’s about it. I’m wondering what about it you liked Adrielle?

Qiana– “Tell some different goddamn stories!” Exactly! But, yeah, your question back to me is a good one. You’re right that it is a pretty common problem; strip away the art and take a look at the story on its own, and…meh. I do think that some creators manage it (i.e. offering a story with complexity and well-wrought language), though, including Mazzucchelli.

Noah–I gather from Qiana’s comment that this comic has received significant critical acclaim for its design, but I am more or less ignorant of the work’s reception. Speaking as a newcomer to Daytripper, I was most struck by the immersive quality of the visuals, which is not–I agree– entirely apparent through just a few sample panels pulled out of context. As you move through the chapters (which were the original separate single issues), you are pulled into the atmosphere of scenes; each scene is significantly differentiated from previous scenes, based on character mood, location, etc. I often feel a sameness across a work, and the creators of this one (notably the colorist, actually) worked hard to build a believable world–both fantasized and realistic–that sucks one in. Hard to isolate elements (beyond color), though; it’s not quite panel layout by itself, or linework….I do know that I like the way Daytripper offers a less repetitive panel structure, close-ups, distance shots, and everything in between…It’s effective, really.

I think Qiana was right to question what happens when one “sets” aside the design/images. Perhaps one can’t do this without fundamentally altering the story (in other words, is the extracted text–words–identical to the text when in its proper context?)

Provocative questions, Noah and Qiana. Thanks!

I really didn’t like Asterios Polyp much either. We did a roundtable on it a while back.

I’m still slightly befuddled that anyone considers Daytripper “beloved” as Qiana suggests. It’s an entertaining enough graphic novel, but gets repetitive and dull. The only saving grace is the brothers’ art. I am a fan of Moon & Ba, especially their work with Matt Fraction on Casanova, but I find their writing to be more than a little twee. De: Tales, their collection of black and white shorts is very similar thematically, just without the hook of the repeating death.

I approached Daytripper with quite a bit of interest, but more in how the finished product combines the two artists similar though distinct-enough visual styles. The idea of two cartoonists working around and over and with each other in one unified presentation is still fascinating to me and an experiment I don’t see often outside of the perfunctory jam-sessions we get from mainstream publishers on certain projects. The finished product in Daytripper is most definitely striking, but only in image and certainly not in narrative.

—

I found this stance from Adrielle’s piece fascinating, and a bit odd: “Since I actually weight the visual more heavily in graphic works, I try to avoid treating comics as standard text narratives, since this is nearly always a reduction of the comic.”

The thing about comics is that they *should* be approached as “standard text narratives,” or more accurately as narratives first with the elements that make up that narrative – writing, art, lettering, design, presentation – no different than any visual storytelling media. To approach comics as art-first, story-second is aesthetically valid as any other approach, I guess, but fails to recognize comics as a storytelling medium first and foremost. The art is absolutely important, but shouldn’t be the sole point, or the work fails as a comic (“comic” defined in my mind as “narrative art”). If something is pretty to look at but doesn’t actually tell a story (outside of whatever interpretation from the viewer), than it is non-narrative. (An art-film, for instance, could be a motion picture, but it is not necessarily a “movie.” Just like most “abstract” comics can claim to have a narrative but aren’t “comics” in my mind.) And to apply non-narrative standards to something inherently, necessarily narrative, misses the point. Treating comics as narratives is the point, or we’re not discussing comics.

Okay, well, I’ll swap the term “beloved” for something just as subjective but perhaps more precise and say “well-respected by critics.” It won an Eisner and a Harvey and a few other industry awards and received many positive reviews. Not saying that we have to agree. But a lot of readers seemed to enjoy it.

And I very much agree that narrative is key (I think Adrielle would agree with this too) but I still feel like I’d want to concede that there are times where the narrative may not be as readily apparent (to me) – which would leave some room for abstract comics to be comics, I guess. Do abstract comics claim not to have a narrative at all? I’m not as familiar with them.

I don’t believe there is narrative intent in most abstract comics – if you can even call the things comics – but I admit to being perhaps a bit narrow-minded about that.

I DO like abstraction in narrative art. Anders Nilsen’s The End, for instance, mixes interpretive abstraction within a very clear sequential narrative. And it is powerful and moving, if uneven. (I wrote about it a bit here: http://comicpusher.blogspot.com/2013/06/NilsenEnd.html)

Re: The commercial and critical success, I agree completely. A lot of folks do like the book, and when I was in retail, it was a very easy book to sell (sadly easier than Casanova).

Oh, and Qiana, re: abstract comics. I think Andrei Moltiu tends to argue that there doesn’t need to be a narrative (he talks about sequence not necessarily being narrative, I think.) Derik Badman’s comics aren’t necessarily narrative (though I talk about the way he plays with narrative here.)

Also I talk about the way Lilli Carré turned her gallery show into a comic here. That’s a vision of comics as juxtaposition and sequence rather than as narrative per se, I think.

Pushing comics towards non-narrative definitely gets you moving towards high art, whether poetry or the gallery. I think comics has traditionally been more cmofortable nestling up against literature or (narrative) movies, and so for some folks that ends up being what comics is. I don’t think that’s what it has to be though.

Many thanks for these links – and also Jeff, for directing me to your review of Nilsen’s The End!

Fascinating discussion. As a narrative-centric person (trained in literature, not art), I guess I begin from your premise, Jeffrey (that narrative is critical, if not primary), but graphic works have taught me to be careful here, mostly because those of us beholden to the word often give short shrift to the visual. When I read reviews or essays on comics that go on at length about the story and quote only text, I worry. Though it seems important to hold both in our attention at once (as interwoven elements), I think I’ve come to the position that the art holds a slightly dominant position (remove it, and it’s not a comic anymore; remove text and it still is, even if there are gaps, missing information, etc.)

Pingback: How Many Days Did Your Father Give?: Daytripper & Sons | White Tower Musings