Matt Kindt’s Mind MGMT (by Dark Horse Comics) unfolds like a dream. Not like a Hollywood dream, where, despite some strangeness, the dream remains coherent and dictates useful messages to the protagonist to be sussed out in waking life. Nor like the constructed dreams in Christopher Nolan’s wildly overrated film Inception. That film had the worst representation of dreaming I have ever seen. Its insistence that dreams have to “make sense” or else the dreamer will awaken is at odds with how severely and fascinatingly strange dreams can really be—a strangeness our dreaming selves can sense or even question, but that does not disrupt the dream. In fact, it is the very understandable abruptness of the sensation of falling or violence that often startles us awake, not the strange, not the incoherence of the dream. The kinds of compression and transference that occurs in dreams—the conflation of people, the access to pure knowledge, displacement of people and events in time, the superimposition of places, the transgression of social norms, etc…—is the normality of the dream-world. The cold sleek video game-like architecture of Inception is really the death of dreams and of human imagination—plus, the film itself is a mess that fails on the many levels of genre it tries to emulate. Inception completely misses what makes dreams useful and fun. Dreams are malleable protoplasmic psychical energy that functions as a form of mind management that resists interpretation, and that is often diminished by attempts to do so.

The problem with representations of dreams in literature and movies echoes Susan Sontag’s concerns in her seminal essay “Against Interpretation.” She writes, “Interpretation takes the sensory experience of the work of art for granted, and proceeds from there.” The same is true for dreams. In her indictment of the interpretive impulse of the contemporary critic, she of course brings up Freud, whose work, despite being widely discredited, has permeated Western views of art, relations, culture, what-have-you, to such a degree as to become a nearly invisible force. He remains unnamed, even as his terminology is put to use or re-appropriated in the language of not only critics, but everyday conversation. Sontag’s concern with the hermeneutics of Freudian interpretation emerges from the problems inherent to the manifest content of the dream (“the dream” in this case being the stand-in for “art”) being a transformation of an unreachable latent content. As Freud writes in The Interpretation of Dreams, “I am led to regard the dream as a sort of substitute for the thought-processes, full of meaning and emotion, at which I arrived after the completion of the analysis.” The emphasis there is Freud’s, but if I were to emphasize something it would be: at which I arrived. This is nothing new, I guess, but the idea that Freud or his psychoanalytic protégés serve as gatekeepers for secret knowledge gleaned from the free association of dream material is laughable. Freud’s own writing feeds this doubt. He admits the over-determined nature of dream imagery, making their connection to a singular source (and thus meaning) impossible. He explains that “[Dream-work] only comes into operation after the dream-content has already been constructed. Its function would then consist in arranging the constituents of the dream in such a way that they form an approximately connected whole, a dream-composition.” In other words, even telling a remembered dream, even before its content is analyzed, is a form of preliminary interpretation. This form of dream-work deals with the consideration of intelligibility. To re-tell the dream the dreamer must order and edit the dream and/or make poor excuses to mitigate its incoherence. “And somehow, despite looking like mi abuela’s nursing home, I knew it was my college cafeteria…”

The problem with representations of dreams in literature and movies echoes Susan Sontag’s concerns in her seminal essay “Against Interpretation.” She writes, “Interpretation takes the sensory experience of the work of art for granted, and proceeds from there.” The same is true for dreams. In her indictment of the interpretive impulse of the contemporary critic, she of course brings up Freud, whose work, despite being widely discredited, has permeated Western views of art, relations, culture, what-have-you, to such a degree as to become a nearly invisible force. He remains unnamed, even as his terminology is put to use or re-appropriated in the language of not only critics, but everyday conversation. Sontag’s concern with the hermeneutics of Freudian interpretation emerges from the problems inherent to the manifest content of the dream (“the dream” in this case being the stand-in for “art”) being a transformation of an unreachable latent content. As Freud writes in The Interpretation of Dreams, “I am led to regard the dream as a sort of substitute for the thought-processes, full of meaning and emotion, at which I arrived after the completion of the analysis.” The emphasis there is Freud’s, but if I were to emphasize something it would be: at which I arrived. This is nothing new, I guess, but the idea that Freud or his psychoanalytic protégés serve as gatekeepers for secret knowledge gleaned from the free association of dream material is laughable. Freud’s own writing feeds this doubt. He admits the over-determined nature of dream imagery, making their connection to a singular source (and thus meaning) impossible. He explains that “[Dream-work] only comes into operation after the dream-content has already been constructed. Its function would then consist in arranging the constituents of the dream in such a way that they form an approximately connected whole, a dream-composition.” In other words, even telling a remembered dream, even before its content is analyzed, is a form of preliminary interpretation. This form of dream-work deals with the consideration of intelligibility. To re-tell the dream the dreamer must order and edit the dream and/or make poor excuses to mitigate its incoherence. “And somehow, despite looking like mi abuela’s nursing home, I knew it was my college cafeteria…”

Sontag is right that in making the meaning of the dream the primary concern, the experience of the dream is lost. She warns that the over-emphasis on the content of art devalues critical concern with its form. In the case of dreams, we seem to have something that resists attainable meaning in terms of its images, scenarios, sensations, but whose form is predicated not on its experience, but on its telling—a telling that requires a bit of both conscious and unconscious interpretation. She writes that “interpretation makes art manageable, comfortable,” and that certainly falls in line with Freud’s interpretation of dreams. In Freud’s view, dreams are a form of wish fulfillment in which the latent conflicts our conscious mind will not let us express manifest themselves in the incoherent and fragmented experiences of the dreaming vision and sensation. Dreams then are a form of safety-valve that lets out the pressure built within the dreaming subject through conflicts between id and super-ego but that transforms them from the literal desire into the strange and symbolic. The dream manages the mind’s discomfort with the mind’s own anti-social taboo desires. Maybe. Maybe not. Whatever the source and function of the dream experience, more time needs to be spent with the dream itself—with the dreaming of it. The same is true in literary analysis. More time must be spent with the text. Whatever my other theoretical concerns may be with any text, the foundation of the work is the experience of (close-)reading.

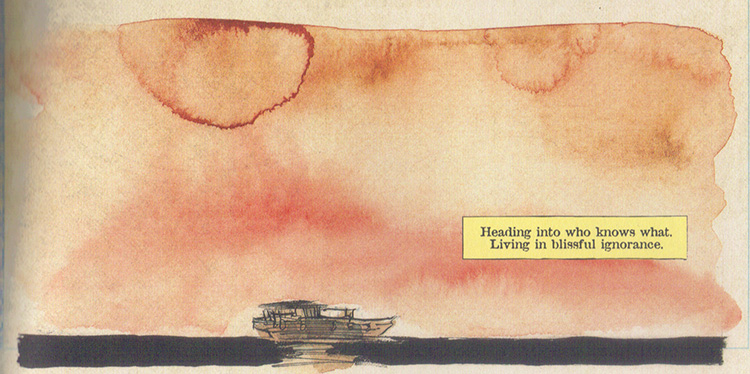

Mind MGMT provides ample material for just that—spending more time with the dream itself. It is a fantastic example of how compelling dreams can be. While the series itself does not purport to convey a dream world like Nolan’s Inception or 1984’s cheeserific Dreamscape, it constructs a dream-like world nonetheless. In fact, since its world slowly unfolds through the eyes of Meru (or sometimes—as in a dream—from outside of herself) without calling itself a dream, the sense of it being dream-like is all the more compelling. Furthermore, the inclusion of strange complimentary stories, mission briefs and directives in the margins of its pages, provides hypnogogic knowledge—the sense of just knowing something, as you often do in dreams. In this way, Mind MGMT avoids even the certainty of doubt, and lets the reader float along as layers of secrets are peeled away to reveal more mystery.

Reading the first collected volume, The Manager, the series begins with a reference to dreaming, with the focus of it panels shifting from a fighting couple falling from a balcony, to a figure on the street below throwing a Molotov cocktail into a bookstore window, to a man walking by the burning store to shoot another man in the head, but who in turn has his throat slashed by a woman with a large knife. The captions read: Ever have a dream that is like a story? And at the end of the dream there’s a twist ending? Some kind of shocking surprise? How can your mind do that to you? You’re creating the dream.

These multiple shifts of perspective in the first couple of pages set the tone for the rest of the series. A blacked-out panel provides the only transition to the “real” story, Flight 815 (a Lost reference–Damon Lindoff wrote the intro for the first collected volume) where all passengers and crew apparently and very suddenly lost all their memories. Two years later they have not regained them. This disassociation is shared by Meru who “awakens” in her apartment with no food in her fridge, a table full of past due bills and her ”new” idea to write about the amnesia flight, a follow-up book on her true-crime bestseller. However, upon calling her literary agent, it appears as if the idea is not as new as it seems to her. Somehow he already knows, but this does not strike her as strange. Sensing something familiar even as she starts a project anew, Meru’s hunt begins to find Henry Lyme, who according to the flight manifest, boarded the plane, but was not among those who got off when it landed.

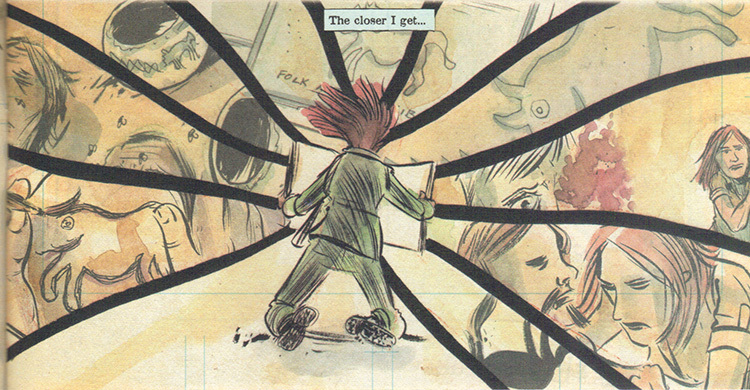

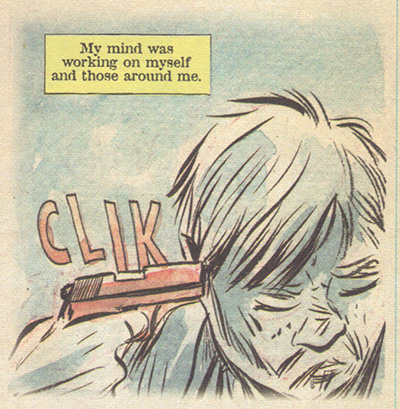

A dream is a strange limbo in its ability to put the dreamer in a state of simultaneous knowing and unknowing. There is a great library of knowledge immediately accessible to you—you just know things and the experience of the dream cannot shake that knowledge. Conversely, there is the experience of cognitive dissonance—not accessing what you know you know. Meru’s search for Henry Lyme becomes one of these simultaneously impossible and possible tasks that even accomplishing does not accomplish. As complications increase, she becomes enmeshed in a complex plot of agents and former agents of Mind MGMT—a defunct and yet somehow still-functioning agency of paranormal people: immortals who can recover from any wound, animal empaths who teach dolphins to talk, people who can see the immediate future, ad writers who can encode brainwashing messages into their ads, a man who can kill by pointing his finger, and so on. Meru’s investigation for her book — which should be at least somewhat routine given her previous success at investigating “true crime” and writing a best-selling book — becomes mired in a fruitless cycle of discovery and amnesia—a deep questioning of the “true.” Secrets are peeled away to reveal more secrets, more mysteries. Mind MGMT, both the comic and the agency it is about, is a journey through layers of secrets hidden by barely disguised suspicion that serves as a fetish—obsession with peeling away the façade of intelligibility of the dull everyday waking life in search of more intelligibility, which itself can only be another layer of façade—an eternal onion with no center. If the cycles of the dream experience are allowed to continue it becomes the substitute for understanding through interpretation. Each latency is the manifestation of another latent conflict.

Meru’s quest—and thus the reader’s—however, becomes not about learning some truth, but about constructing some form of legibility in a world that increasingly seems like it has no stable framework. Meru is learning to interpret this dream she is living in. As such, Kindt’s book becomes about the experience of interpretation, of encoding intelligibility upon the unintelligible. It challenges the reader to take up Sontag’s perspective on art regarding the experience of it, while providing an experience of the intellectualized process of interpreting it.

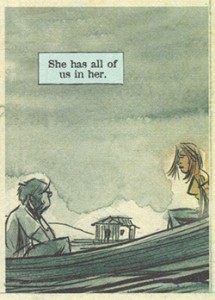

The transformation of discovery into more mystery is reinforced when even finding Henry Lyme fails to lead to an end, but just turns Meru’s quest back on herself. She is the source of mystery, or at least the mysteries she explores in the outside world are just mirrors of her own half-remembered history—the self-created dream with the surprising end. Even her name, Meru, calls to mind Mount Meru, a sacred mountain in Hindu, Jain and Buddhist cosmology, considered to be the center of all the physical, metaphysical and spiritual universes, suggesting that she is the source of all she investigates. In Lacanian terms her self only exists as a symbolic relation to an unattainable self. The self is a narrative that is told through a dream language of expanding and compressing symbols that can never be read the same way twice.

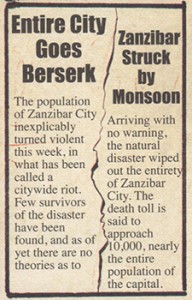

As such, Meru’s hunt for herself is in relation to a fluid dream vision of history in Mind MGMT —tensions between Mind MGMT and a Soviet counterpart either parallel Cold War anxieties, or a schism in the agency creates them. A variety of crimes and disasters, Hollywood murders, Zanzibar tsunamis, suburban riots, university uprisings, the undefinable terrors of human history are revealed to be the results of Mind MGMT agents working with or against orders—who can tell? Some agents are put into a form of sleep, unaware of their mission or abilities, until awakened, accidentally or intentionally to cause mayhem when the conflicts of a constructed life and their secret lives come to the surface—but even that secret life might turn out to be constructed when picked at again. As the story progresses Meru moves from the periphery to the center. The CIA agent tailing her and apparently ignorant of Mind MGMT may have once been her lover and one of their recruits as well—knowledge and relations are suddenly constructed from nothing with equal measures of doubt and certainty. Examining the panels of early issues reveals that figures later revealed to be involved in the layered conspiracies were there all along, in crowd scenes, in the background, as a shadow. Kindt succeeds at making the coincidental seem planned and vice-versa. Mind MGMT exists to shift public opinion and fulfill political goals, but also to police itself. The world is managed and the managers are managed until all sense of origins is lost. There is no unmanaged mind. It is always already managed—managing itself, managing others into managing it. And so on. To arrive at a place against interpretation is to have interpreted your way there.

As such, Meru’s hunt for herself is in relation to a fluid dream vision of history in Mind MGMT —tensions between Mind MGMT and a Soviet counterpart either parallel Cold War anxieties, or a schism in the agency creates them. A variety of crimes and disasters, Hollywood murders, Zanzibar tsunamis, suburban riots, university uprisings, the undefinable terrors of human history are revealed to be the results of Mind MGMT agents working with or against orders—who can tell? Some agents are put into a form of sleep, unaware of their mission or abilities, until awakened, accidentally or intentionally to cause mayhem when the conflicts of a constructed life and their secret lives come to the surface—but even that secret life might turn out to be constructed when picked at again. As the story progresses Meru moves from the periphery to the center. The CIA agent tailing her and apparently ignorant of Mind MGMT may have once been her lover and one of their recruits as well—knowledge and relations are suddenly constructed from nothing with equal measures of doubt and certainty. Examining the panels of early issues reveals that figures later revealed to be involved in the layered conspiracies were there all along, in crowd scenes, in the background, as a shadow. Kindt succeeds at making the coincidental seem planned and vice-versa. Mind MGMT exists to shift public opinion and fulfill political goals, but also to police itself. The world is managed and the managers are managed until all sense of origins is lost. There is no unmanaged mind. It is always already managed—managing itself, managing others into managing it. And so on. To arrive at a place against interpretation is to have interpreted your way there.

There is a moment early on, when Meru—being simultaneously led and followed on her hunt for Henry Lyme—is alone in a Chinese jungle. The text reads “She’s stripped down to nothing. Just a translator. No provisions. No map. No weapon. But…no rent due, no utilities turned off. No bounced checks.” The suggestion is that this nightmarish adventure is a form of wish fulfillment—an escape from the mundane responsibilities of her life. And yet, at that point the narration is Lyme’s voice, not hers. He is narrating her desire and perspective. She sees herself from without. The concerns Lyme imagines she escapes from are the modern post-industrial concerns of an elite worker class that finds itself scraping by as the apparent systems of world capital fail it. It is not until Meru finally finds Lyme, that the narration shifts and her voice takes over telling the story. Could it be that that those everyday concerns are also a form of wish-dream? Lyme’s word balloons are blotted out by Meru’s narration in caption boxes, and for the first time she seems to awaken into her real self through his telling her of his own history—but even that will come into doubt. The timelines of their narratives don’t match up, nor do the identities and motives of the people they involve. As in a dream, times, places, events, people are unanchored.

As the story unfolds and collapses, Kindt’s art beautifully reinforces the dream vibe. The use of watercolor throughout creates a fluidity marked by the translucent saturation only possible with that medium. The panels are a bit of dreamy haziness as the color bleed out of the penciling in several places. Furthermore, the panels are placed within the confines of non-photo blue guidelines that indicate the area on the page within which Mind MGMT agents are to print their reports, creating a juxtaposition between the wash of uncertain color and the officiousness of the blue ink’s message. The comic itself is uninterrupted by ads, except those that seem to be selling something encoded with secret messages to possible Mind MGMT recruits—but to further confuse the issue, sometimes the back page seems to all have small classified ads for actual comic shops and the like.

Ultimately, there is something Foucaultian about Mind MGMT and its depiction of the relationship between power and knowledge. In the series, power is dispersed globally and manifested through the creation of knowledge. As Foucault reminds us, not only does knowledge equal power, but more surreptitiously, power equals knowledge. The Mind MGMT agents use their powers to create, destroy and shape knowledge for each other, for themselves and for the world at large. The very concept of “meaning” loses all meaning when experience is shunted aside as a valuable category by the Freudian hermeneutics that freely associate discrete categories of latent meanings to infinite manifestations. Mind MGMT effectively demonstrates that the distinction between experience and interpretation is a false dichotomy. The mind is always already managed. Returning to Lacan, I can’t help but think of his concept of the unattainable Real. It is impossible to exist outside the symbolic. As such, rather than concern ourselves with the categories of experience (of the body and the senses) and intellect (of the mind), it is better to perceive the human condition as the Sinthome (symptom without cause). Meru’s troubled stories (for Mind MGMT arcs overlap and partially efface each other) are a telling of the sinthome, which “can only be defined as the way in which each subject enjoys (jouit) the unconscious in so far as the unconscious determines the subject.” Mind MGMT revels in that sometimes (often times?) frightening space of the undifferentiated conscious and unconscious and finds joy in being, but understands simultaneously that to be is to be in relation to being.

Ultimately, there is something Foucaultian about Mind MGMT and its depiction of the relationship between power and knowledge. In the series, power is dispersed globally and manifested through the creation of knowledge. As Foucault reminds us, not only does knowledge equal power, but more surreptitiously, power equals knowledge. The Mind MGMT agents use their powers to create, destroy and shape knowledge for each other, for themselves and for the world at large. The very concept of “meaning” loses all meaning when experience is shunted aside as a valuable category by the Freudian hermeneutics that freely associate discrete categories of latent meanings to infinite manifestations. Mind MGMT effectively demonstrates that the distinction between experience and interpretation is a false dichotomy. The mind is always already managed. Returning to Lacan, I can’t help but think of his concept of the unattainable Real. It is impossible to exist outside the symbolic. As such, rather than concern ourselves with the categories of experience (of the body and the senses) and intellect (of the mind), it is better to perceive the human condition as the Sinthome (symptom without cause). Meru’s troubled stories (for Mind MGMT arcs overlap and partially efface each other) are a telling of the sinthome, which “can only be defined as the way in which each subject enjoys (jouit) the unconscious in so far as the unconscious determines the subject.” Mind MGMT revels in that sometimes (often times?) frightening space of the undifferentiated conscious and unconscious and finds joy in being, but understands simultaneously that to be is to be in relation to being.

—-

This post has been cross-posted at The Middle Spaces.

Matt Kindt himself retweeted a link to this, which is neat. At least one person’s read it. :)

Aw man; sorry for not commenting! I haven’t read the original comic, so I didn’t know that I had a ton to say. You do make the book sound really appealing though.

Pingback: Need To Know… 20.1.14 | no cape no mask

Pingback: Need To Know… #47 | Orbital Comics