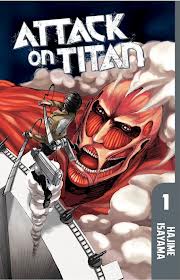

Arguably the hottest title in manga right now on both sides of the Pacific is Isayama Hajime’s Shingeki no Kyoujin distributed by Kodansha in English as Attack on Titan.

When I last visited Japan in October it was impossible to hit any even marginally geeky entertainment area and not be greeted with the sight of this face

looming over game machines and advertising displays. My wife turned to me and asked “Is that a good guy or bad guy?” but I was unable to answer, having neither read nor watched any of it.

Fast forward a few days and I am standing at the Kodansha booth at New York Comic Con, speaking with the editor of the series, while everyone spins slowly in place. (I had flown back from Japan the night before.) He asks me what I think of the series. I look around at a Javits filled with people cosplaying characters from the series and admit for a second time in a week that I have not read it. The editor asks me perkily to please read it, he really wants to know what I think. So I read it. And here’s what I think.

Attack on Titan begins with humanity on the ropes. Continually attacked and eaten by eunuch giants, known as Titans, there is a small pocket of humanity holding out behind the walls of a city. The story opens with the Titans breaching the outer wall, while the military dies at their hands. The human military is split into three divisions – the wall guard, the elite military police, who stay with the King behind the innermost walls, and the Survey Corps which includes the most talented fighters…and is certain death, as they most regularly and most directly face the Titans. The manga follows the lives and deaths of new recruits to the military focusing, as manga often does, on their backstories, their teamwork – or lack of it – and their development as characters.

Isayama’s art starts off unpracticed, with a blocky out-of-proportion feel that is very common among non-professional self-published comics, known as doujinshi. Poor drafting skills mean heads sit awkardly on disporportionate necks. But the first time you see this:

you forget to care.

After the initial shock, and the slow, gut-wrenching realization that the most-used expression in this manga will be one of traumatized disbelief, you settle into a somewhat self-protective objective analysis of the details…the vertical maneuvering equipment, a sort of steampunk jetpack with wires and a mysterious energy source that conks out inconveniently; the feudal government, and impossibly agriculture-centered society. But that’s only meant to distract yourself from the sound of the Titans grinding people up as they chew that invariably invades your mind as you read.

It was Volume 2 when I suddenly realized that Attack on Titan was a zombie story. Immediately I was disappointed. Zombie stories do not interest me, particularly. But I kept reading, because I had been tasked with noticing two key things.

One of the topics about which I write obsessively is the idea that women in adventure stories are frequently one-dimensional. They have had everything taken from them, and they have nothing left but revenge. Mikasa, the first female lead we encounter, is not entirely free of this. Her tragic backstory does include the ritual requirements of no agency or society, as her family is slaughtered and she herself traumatized. Predictably, the story gives her a purpose in Eren, the lead male, who saved her as a child and so she will dedicate her life to saving him. This single-point focus – what amounted to a monomania in her character – did not endear her to me. But, unusually for an action manga series, she is not the only female.

In fact, Attack on Titan is chock full of male and female characters with more than one quality each. Jean is cowardly, until he surprises himself, Annie is selfish and predatory, but there’s more going on with her than we know at first. Armin is not especially strong, but pushes himself physically as well as mentally. The female characters are as likely to be ambiguously “good” or “bad” as the male characters. They develop allies and enemies situationally. There is no “mean girl” clique, although cliques do form, develop, break up and redevelop before our eyes. But the cliques, like the military as a whole, are fully intersectional. This fact was the first thing the editor wanted me to note. So noted.

When Ymir, a relatively unlikable human female, first develops an affection for what appears to be another female with a traditionally tragic backstory, I thought nothing of it. When their backstories turned out to be critical plot points, I stopped doubting Isayama. Unexpectedly for this kind of manga, with an ensemble cast, he does not establish characters then let them coast along. He’s got a plan and all the chess pieces, male or female, have a role. The fact that many of his characters are not at all decent people actually adds to the appeal of the story. Humanity, as we know, is not all good or all bad. Isayama trusts his readers are adult and intelligent enough to not require characters that are one-dimensional. It is not at all common in a seinen manga to have female characters as fully developed as the males. Female readers are not sidelined by the Titan narrative, nor are they boxed into waiting for the obvious romantic pairing or manufacturing fantasy pairings in order to engage with the narrative. (That said, derivative fantasy narratives abound for this series, as one might expect.)

The second and most specific thing I was asked for my opinion on is the character, Zoë Hange (pron:Hanzh).

The second and most specific thing I was asked for my opinion on is the character, Zoë Hange (pron:Hanzh).

In Japanese, you may remember, the honorific that is most commonly used “-san,” is not gendered in any way. In English we translate it to fit the sex of the character – Mr./Ms., but in Japanese, gender can be written around relatively simply. When Hange-san arrives in the narrative, Japanese fans wondered if Hange was male or female and eventually Isayama went on record to say “whatever you want Hange to be, Hange is.” Initially, he meant for Hange to be a masculine female, the editor told me. So when Hange shows up, I was interested to see how I interpreted the character. It struck me instantly that I saw no ambiguity at all. To my biased eyes, Hange is female, full stop. The English language edition of the manga chooses for you, so “Ms. Hange” it is, regardless of your intuition. (See the comments for an update on this from Kodansha.) What interested me most was than anyone saw Hange as androgynous, where I just didn’t. I’m glad the author has maintained Hange’s androgyny. It provides a layer of legitimacy to LGBTQ fans of the series, along with the Ymir and Krista pairing and the inevitable fantasy pairings of Captain Levi with every male character he comes in contact with. Isayama is making it it easy for male, female and LGBTQ fans to engage with the narrative as equals.

Attack on Titan is a uniquely constructed post-apocalyptic giant zombie story. This hits the zeitgeist in a number of places that make it likely to be popular even if it was so-so. As of Volume 11, it is not a so-so story.

Typically, manga has the qualities of working together, fighting against unbeatable odds, growing stronger…and this series has that, with a possibly not-happy end game. It’s appealing to teens and adults who want something more gritty than rubber pirates who always win. In terms of character, there’s someone for every reader/watcher to like and /or hate. And not in a typical checklist kind of way (“I like redheads with pigtails, so I like that character.”)

In addition, this series has saturation. This is the single common factor that the top anime and manga series of the last 20 years all have have. In Japan, this means tie-in brands and goods that range far from the source material, and a constant stream of advertising in the magazine, on TV, in stores. Here in the west we don’t often get that. Through luck of the draw (because I know the two companies in question did not coordinate) Attack on Titan has an anime that is streaming free and legally on Crunchyroll at the same time the manga is coming out. (The manga is also now simulpubbed on Crunchyroll, as well.) Taken all together, it’s a recipe for success.

Now, I wait for new chapters just like everyone else, wondering if there is actually an endgame for this series.

I certainly hope so.

Via C. Lamerichs, I have learned that “Isayama sent instructions to Kodansha (who’s translating the manga) to stop referring to the character as “her” and instead try to work around it as well. It’s a little too late for volumes already released, but the new releases (and rereleases of previous volumes) will be ‘fixed’.” (http://kodanshacomics.tumblr.com/post/73423029266/i-have-the-attack-on-titan-books-and-you-said-that)

This is a very positive development in regards to Hange’s continued androgyny.

The point about the linguistic difference between English and Japanese in terms of being able to refer to someone without gendering them is interesting in a few ways, I think. In English preserving a character’s androgyny is relatively difficult while it’s far easier in Japanese. That might mean that we, the English audience, attach more legitimacy to an explicitly androgynous character than the Japanese audience might.

Being able to easily avoid gendered language means that not using it in Japan doesn’t really have any implications. It’s a blessing and a curse, because while you – for instance – can easily talk about your romantic partners in Japanese without giving away that they’re the same gender you are, or talk about an androgynous person without (mis)gendering them, it also means it’s easy to fall into a trap where you just avoid the language that implies anything even if you’re an out and proud type, which doesn’t help visibility.

So while I applaud Isayama for being inclusive, I can’t help but wonder if the Japanese audience is reading anything into it in Hange’s case.

Excellent point, Emma.

The answer is, realistically not homogeneous for “Japanese audience.” Sexual/gender minority fans, or those people who favor ambiguity might well read significantly more into it than a sexual/gender minority.

I also imagine that doujinshi creators find Hange to be fruitful ground, if you will.

This is, as I say, one of the strengths of SnK – minority portions of the audience are still allowed to engage directly, rather than obliquely, with the narrative.

Sorry, previous version cut and pasted with uneditable errors:

Excellent point, Emma.

The answer is, realistically not homogeneous for the “Japanese audience.” Sexual/gender minority fans, or those people who favor ambiguity might well read significantly more into it than a sexual/gender majority.

I also imagine that doujinshi creators find Hange to be fruitful ground, if you will.

This is, as I say, one of the strengths of SnK – minority portions of the audience are still allowed to engage directly, rather than obliquely, with the narrative.

Reminded me that I’m behind on the manga! It’s got an addictive quality to it since the characters are always getting stronger and then getting terrorized and then getting stronger and then getting terrorized again, and everything they’ve accomplished can be taken away at any moment. Plus there are lots of mysteries and yeah, Isayama is A Man With a Plan. It’s also true that there are a lot of great female characters in this series.

I think that Mikasa couldn’t be less one-dimensonal than that. Actually, she’s less one-dimensional than the main protagonist, Eren. Although it is true she is a monomaniac character, she’s one of the deepest. Her obsession isn’t shallow or simplistic, it is quite well drawed: the scene where she compares her parents being butchered to her parents butchering stock animals for food, and to a mantis slaying a butterfly, as in there was nothing to be seen in life but death, gives her much more depth than Eren ever gets. Her nihilism is more detailed and explained than Eren’s mindless desire for freedom.

After all, we’re talking about a teenager who lost her parents twice in a couple of years, and that dedicated the next 5 years to fight the zombie apocalypse. I’ve never read a traumatized teenage male character with more depth than Mikasa, not even in actual literature. Obssessive people with small life experience can’t be more nuanced than that. What’s really weird and unrealistic is how Reiner, for example, has so much insight and life experience being so young.

Pingback: Okazu » Attack on Titan Manga, Volume 10 (English)