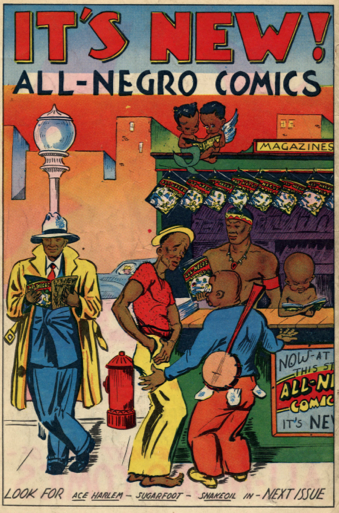

When Philadelphia journalist Orrin C. Evans published what would become the first and only issue of All-Negro Comics in 1947, he boasted that the comic book showcased original stories about black life and adventure with African and African American characters in positions of authority, strength, and trendy style. The comic’s commitment to wholesome, affirming images of black people was underscored by the fact that its artists, too, were African American. Evans even included a photograph of himself inside the cover, thereby confirming the extent to which the comic earned the “all” Negro distinction.

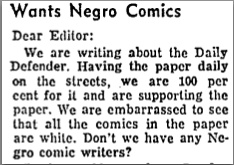

By the mid-1950s, readers of black-owned newspapers had become accustomed to seeing the work of black comics creators like Chester Commodore and Jackie Ormes included among the reprints of syndicated comics. When the daily edition of the Chicago Defender failed to include black comic strips, readers wrote to complain:

This question, posed in March 1956, may sound all too familiar. Nevertheless, much has changed since the 1950s. So much so that “African American Comics” could easily constitute a category of its own (and not just as a display during Black History Month). But exactly what kinds of comics would fall under this designation? Would it only include publications that follow the All-Negro Comics model where black writers, artists, and editors can claim “every brush stroke and pen line” of the final product, or should the term be expanded to any comic about African Americans? Should the stories reflect particular ideological investments? Be recognized by a specialized community of readers and critics?

I also struggle with these questions in my research and teaching in African American literature, where the relationship between naming, visibility, and power is much more pronounced and deeply connected to the exclusionary politics of literary canons. In the classroom, I’ve had to step away from the anthologies that track a narrow, reactionary path from the New Negro to the Black Arts aesthetic. I try to emphasize instead how each successive wave of redefinition attracts new possibilities along with new intersectional silences and contradictions, or as the late Amiri Baraka put it in his 1966 poem, “Black Art”: “Fuck poems/and they are useful.”

The history of African Americans in comics reflects many of these same cultural tensions, but the narrative unfolds much differently. I recently taught a course on “African American Comics” that began with examples of 19th century racial caricature. We studied George Herriman’s comics, discussed All-Negro Comics, as well as genre comics from the 1950s-1970s before moving to more recent graphic novels. I did not begin each new comic identifying the racial identity of its creators, unless one of them made it an issue, for instance, as Christopher Priest did in his terrific introduction to the trade paperback of Black Panther Vol 1. The Client (reprinted here.) The class went very well, but by the end I knew that my title had been inadequate – if not inaccurate, since I also included Aya: Life in Yop City (African, but not American).

So I’m genuinely interested in what people think. What is an African American comic? Is there a way that this term might be useful? Is it too reductive or so broad that it loses all meaning? With Milestone Comics recently celebrating its 20th anniversary, these concerns seem more relevant than ever. We could even extend the question to other social groups – women’s comics? LGBT comics? And remember, Black History Month is upon us. So refusing the question doesn’t mean that someone else won’t try to define it for you.

So, two things. Could you explain for ignoramuses like myself would you mind expanding on why the path from New Negro to Black Arts is reactionary, and what some alternatives are?

Maybe slightly more helpfully in terms of your question; I wonder if genre studies would be a useful lens here at all? I’ve talked about this here before, but there’s at least some genre studies discussions which see genre categories as amorphous and socially constructed; that is, there’s no hard formal line around what is science-fiction, but instead there are various definitions based on audience expectations, institutions, and so forth. Jason Mittell even argues that genres are constructed as much by people who don’t necessarily know about them, or aren’t invested in them, as by people who do (which I think has more difficult application in this context than when you’re talking about sci-fi or television, but still worth thinking about.)

I’m not sure you’d want to think about African-American comics as a genre exactly, but even figuring out why it isn’t or why it differs seems like it might be somewhat useful.

Noah, Black cultural expression in America is defined in part by a productive, if vexing, interaction with whites like Carl Van Vecten Blanche Knopf, Clive Davis, ect. So any attempt to articulate an ‘all Black’ cultural aesthetic minimizes the creative frisson that allowed for the production not just of Hughes’ Fine Clothes to the Jew or Baldwin’s Going to Meet the Man (which was written while he was living in William Styron’s guest house, but also Van Vecten’s Nigger Heaven or Styron’s Nat Turner. We may not like Van Vecten’s text b/c of its title but he was in dialogue with Hughes and each influenced the other. The Black Arts movement and some strains of the New Negro movement called for a nationalistic cultural expression that ignored this reality.

As for af-am lit as a genre….oh boy. I’ll get back to you on that one.

It’s crucial to (re)ask these questions, especially whenever a category starts to seem obvious. I’m not sure genre theory is the best route here, however: there’s enough work on race as itself an unstable and socially constructed category itself. But the conflation of racial identity and genre would just blur ways to talk about African American science fiction, or African American crime stories, etc. There’s a body of work on African American cinema that asks similar questions, but also allows for African American comedy, African American drama, etc. as generic distinctions. The crux, as Qiana indicates, is often in the explicit claim of “All-Negro”: not just content, but black creators (if not black money) behind the scenes. However, there were many films (and comics?) which promised “all-black” casts but were in fact “all-white” productions — the same would be true of many DC and Marvel comics featuring black (albeit never all-black) casts.

Corey, I’m not sure why you think talking about African-American comics as a genre would prevent you from talking about sub-genres, or cross genres. Genres are almost always hybrid and cross-pollinating. Genre theory is pretty clear on that (from what I’ve seen.) The concern about hard divisions and exclusions which you bring up is exactly the sort of thing that it seems like genre theory could allow you to get around.

Also, genres are also almost always based in, or linked to, identities, though usually gendered rather than racial ones.

Really though I was less saying, “treat this as a genre” and more saying that some genre theory approaches (looking at things other than formal or hard and fast designations; not worrying too much about specific definitions, but rather thinking about similarities and cultural reception) might be useful.

One thing to think about in terms of genre theory, for example, is that these designations tend to change over time. So what “African-American comics” means wouldn’t necessarily have to be the same now as it was in the past.

I don’t know, maybe I’m just digging myself deeper — but another thing I get from genre theory is that genres or categories are constituted in multiple ways. So, there’s an issue of who the audience is, of what the content is, of who is creating the content, of where the content is being sold, and so forth. None of those has to be exclusive. So African-American comics could include comics by African-American creators, comics about African-American experience, comics by black people who aren’t African-Americans which can be read in an African-American context (like a course about African-American comics) and even arguably comics that appeared in an African-American newspaper but were created by whites.

I started to reply to this and try to break down what I see and don’t see as an African-American comic and it became really messy really quick.

The only definite I could come up with was comics by African-Americans about African-Americans as they only comics that I would say are unarguably “African-American.”

Everything after that varies widely on a lot of conditions of creators, content, publisher, etc. . .

As such I am not sure that it is much of a useful designation. Lots of comics concern African-Americans both in terms of creator teams and content/characters – but rather than defining what is included or excluded in an amorphous general category, I think it is more useful to think about these various comics as they relate to various forms of African-American representation, culture, history, audience reception, in specific ways rather than an abstract category.

Re: the narrow, reactionary path in AfAm lit – Jonathan sums up the problem quite nicely. The prevailing narrative gives the general impression that black writers speak only to one another, exchanging tropes and creative strategies within an insular community of all-black writers, rather than circulating in multiple circles of influence. I remember being upset when I heard that Toni Morrison hadn’t read Hurston until much later in her career, and that Ernest Gaines grew up reading Dostoevsky not Richard Wright. Now I wish I had been introduced much sooner to the notion that what we refer to as an African American literary tradition did not (does not) develop in isolation. Which makes the problem relevant to comics too – and film, as Corey points out.

I love talking about genre and have ventured only a little into this conversation myself (http://pencilpanelpage.wordpress.com/2012/11/30/delany-essay/) I need to read a lot more, so thanks for pointing me to your essay, Noah, and Jason Mittel’s book.

I agree with what all of you have said, that “African American Comics” is a category that can be constituted in multiple ways, in different contexts, over time. In practice, though – do people really use it that way? I mean… really? I think the difficulty that I’m having is the way the subject matter of a comic is conflated with the racial identity of the creators (as in the letter from the Chicago Defender reader and in the CBR call for a Month of African American Comics). These are two separate issues… important, but separate… but I don’t really see much acknowledgement of this.

Osvaldo: “I started to reply to this and try to break down what I see and don’t see as an African-American comic and it became really messy really quick.” Yep. My sentiments exactly!

Thanks for explaining further re: Af-Am literary influences. That makes a lot of sense.

“In practice, though – do people really use it that way? I mean… really?”

Darryl Ayo on twitter was saying that there aren’t enough Af-Am comics to know what they are. I don’t know if I agree, but I think it’s true that it’s at least something that isn’t discussed a ton, and so it’s hard to know how people do or don’t use it because often people don’t use it at all, it seems like.

John Rieder’s book on imperialism and sci-fi has good thoughts on genre too.

Osvaldo, the way out of this is to concieve of all literature that concerns African Americans as Af Am Lit. The obvious retort would be “but that means that Huck Finn, Benito Cerano and Uncle Tom’s Cabin would all have to be considered Af-Am Lit!” To which I say, exactly. Much of American lit is Af-Am lit b/c it so intimately concerns colored folk. I’m in favor of breaking down genres and building up intersectional geneologies so that Baldwin can peacefully exist in his plenatude.

Regarding comics studies, thinking through intersectional geneologies has the pleasing side effect of greatly multiplying potential objects of scholarly inquiry.

An aside: Greg Rucka’s new book is edited by a black man, David Brothers. Does his involvement make Lazerus somehow a black text? More black than a Luke Cage comic?

I really enjoyed Rieder’s book – pick it up on your recommendation several months ago!

I feel much differently about this issue than Darryl Ayo. There are definitely enough comics by and about African Americans for this question to be relevant. Unless, perhaps, if you are following the “All-Negro Comics” model (which may have folded because the paper supplier refused to sell to Evans for a second issue apparently…)

I’ve pretty well-versed in genre theory, from Aristotle to Rick Altman, and still can’t quite see that as the useful controlling mechanism here: if African American is a genre, then are all other such categories — racial, ethnic, gendered, national, religious, etc.? Are texts we can identify as Jewish, French, gay, etc. genres? For that matter, are texts produced and about straight white men a shared genre? Long ago, Thomas Cripps published a book called BLACK FILM AS GENRE, and it’s a fine book, but the genre claim in the title is the weakest thing about it. I met him years later and asked about this and he said, yes, that didn’t make any sense at all. Is genre useful to talk about African American comics? Sure it is, but I don’t think it can be the overarching category. As others are noting, the attempt at definitions always bumps into actual examples: so Matt Baker’s comics are not African American, since he was African American but the people he drew were not? (Hurston, Wright, and Himes each wrote at least one novel centered on whites: so these are not African American novels, whereas the rest of their work is?) But DC’s Black Lightning comics aren’t because the character is black but his creators are white? And, again, what happens when you follow the money? Jesse Rhines’ BLACK FILM/WHITE MONEY raises that question, which could easily adapt to discussions of comics.

Yes, Jonathan – thus the messiness I described above. It became too intertwined to make sense of (at least in a blog comment).

I am inclined to agree with you about the inclusion of texts even if I am reluctant to say that Huck Finn or whatever is Af-Am lit. . . But when I think of something like Luke Cage or Black Panther, created and written by white dude (in most incarnations), but still really important to the black and brown comics fans I know, I can think of no other way to handle it. I mean, shit – Black Panther isn’t even about an American and some of what are considered his best stories (reading his run in Jungle Action currently and hope to write something about it soon) don’t even take place in the States, but his importance to comic readers of color in America and as a result of American publishing means he would have to be included.

Like I said, a mess.

Jonathan, this is I think where I’m headed as well. I even altered the title of my last course on postmodern African American lit so that I could teach this book: (http://www.amazon.com/Jujitsu-Christ-Banner-Books-Butler/dp/1617037389 – which everyone should read!) I want there to be room for these multiple conversations to take place about African American representation and experience. It’s our job to provide context and history, and ask critical questions, etc. Such as this great one you’ve posed about Rucka’s comic.

Hey Corey, Minor point of correction, Black Lightning’s co-creator Trevor Von Eeden is black.

Corey, I’m sure you know way more about genre theory than I do…but then you raise issues as objections which seem to actually confirm the usefulness of genre theory, rather than deny it. So not sure what the disconnect is precisely….

I think discussing the way that “white comics” might constitute a genre could be pretty interesting. Not least because I think whiteness is actually a really major category for a lot of the way comics constructs and thinks about itself. This is a common issue in the discussion of country music — but much less so in comics studies, even though comics (and esp. some segments of comics) is the only cultural phenomena I can think of that approaches country in its segregation.

In country, there’s some interesting discussion about how the genre constitutes whiteness, or sells white peoples whiteness to them, constituting the identity it markets. I think that could be a pretty useful way to look at the history of ethnicity in comics.

And wow, I didn’t know David Brothers was editing Greg Rucka. That’s awesome. (David occasionally reads and comments here.)

Current rhetorical/social genre theory, coming down from rhetoric scholars like Lloyd Bitzer and Amy Deavitt, focuses on communities, uses, and social actions rather than formal characteristics. With that in mind, I agree with Noah about the potential usefulness of genre here.

Qiana, reading Priest’s commentary on his BLACK PANTHER run (thanks for the link), I’m struck by two things: (1) his sense of a dialogue, sometimes a messy and contentious dialogue, with the superhero comics readership, something that he intended to embed in the comics themselves by offering up characters who serve as reader surrogates and satirically mimic the fans; and (2) just how many pop culture references he uses to explain his inspirations (“Friends,” Michael J. Fox, Batman/Ras, Batman/Joker, supermodels, etc etc). It seems to me that Priest’s thoughts on racial representation, “black” comics, etc., are always filtered through this hyper-awareness of pop culture and fandom, so much so that his BLACK PANTHER becomes part of a snarky back-and-forth with what he imagines as the fan community. That to me sheds a lot of light on the possibilities and limitations of superhero comics generally.

On another note, I wish there were even more (beyond Jeffrey A. Brown’s book) scholarly writing about the Milestone experiment, which to me was the most important, albeit not altogether successful, ideological innovation in 1990s superhero comics.

Another way to approach this question might be to ask what a theory of African American comics scholarship might be. As a quick example, what might we borrow from Toni Morrison’s _Playing in the Dark_ as we study what she describes as the Africanist presence in American literature? What would that presence look like, for example, in a Golden Age Superman comic? In one of Harvey Kurtzman’s Tarzan parodies from MAD? In an experimental, abstract, or wordless comic?

Or, to expand our scope, what if we begin drawing more fully on, say, theories of the Black Atlantic from critics like Paul Gilroy who do not, perhaps, write about comics, but have explored other aspects of American and African American popular culture–in Gilroy’s case, music as an expression of the diasporic imagination.

We might also then have new lenses through which to read comics that are more explicitly about race, even pulp comics like Justice, Inc. (to draw on a more obscure example from a well-known creative team). Denny O’Neil and Jack Kirby’s ’70s version of The Avenger (Justice, Inc.) revisits and revises some of the pulp conventions introduced in the Street and Smith magazines of the 1940s, especially in light of the idea of passing and masquerade. Then, by the late 1980s, Andy Helfer and Kyle Baker revised those characters again–specifically, Josh and Rosabel Newton, the Avenger’s Tuskegee-educated allies. A pulp genealogy of that sort would prove more evocative and telling if read and understood, for example, in the same context as literary and historical depictions of passing, from Oscar Micheaux through Nella Larsen to Samuel Delany. And what would happen if we add bell hooks to that mix?

So maybe this is also a question of theory. Qiana, I think your new essay in the Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics is pointing us in this direction–a theory of how we might read all comics through the lens of, as you put it in your title, “visual metonymy” and the “spectacle of blackness.” Perhaps it’s more important that we define a means of talking about comics through a discourse informed by the complexities of African American literary theory first, so that we might then articulate some sort of tradition of African American artists–a journey that would take us from Matt Baker and Jackie Ormes to Grass Green and Reggie Byers and John Jennings and beyond (just to name a few).

The implications and possibilities embodied in this question are very exciting. Thanks for this, Qiana.

Charles, I’m glad you took a look at the Priest intro! I agree that his concern about Panther being labeled a “black book” (i.e. bashing white people) is really instructive, not just in thinking about race, but also superhero comics and a kind of anxiety about fandom more generally. The students in my class spent a lot of time talking about Everett K. Ross and the continued need for him as a “reader surrogate” for Black Panther … some wanted him (Ross) to go away after a while.

Brian, thanks for weighing in! You already know how persuasive I believe Toni Morrison’s approach to American lit is in “Playing in the Dark” – I definitely think that kind of intervention is long overdue in comics studies. (Maybe your next book?) Also: you’ve just alerted me to a new name – Reggie Byers? I’ve never heard of him. Off to Google….

So…Brian, since I am once again not as knowledgeable as I should be…could you give a (very) brief summary of Morrison on the Africanist presence in American literature?

Oh wait; google helps;

That makes sense. As far as golden age superman and similar books go — I think the suerhero as assimilationist fantasy is generally seen as a relationship between Jews and whites, but the third term there is pretty much always African-Americans, and the fact that white ethnics get to assimilate because the only racial divide that really matters in the US is white/black. Superman/Captain America/etc. seem like an ethnic dream of whiteness, predicated on a denial/disavowal of otherness which is surreptitiously (or not so surreptitiously) coded as black. You could argue that all superhero comics are African-American comics in that they’re from their inception concerned with/fixated on blackness (since you can’t disavow what you’re not thinking about.)

Oops about Black Lightning — I actually knew that, too. I agree with Charles about the need for more work on Milestone, which I think was regularly far stronger than its current reputation suggests: it doesn’t help of course that DC only half-heartedly reprinted some Milestone material. It’s also worth noting that Milestone publicity tended to emphasize its aims as multicultural, not exclusively African American.

That’s a good overview of her ideas. I think you’d find the essay really interesting, Noah–and it’s a very concise argument, a map for other writers to follows. This passage from early in the essay sums up her arguments well, too:

“Just as the formation of the nation necessitated coded language and purposeful restriction to deal with the racial disingenuousness and moral frailty at its heart, so too did the literature, whose founding characteristics extend into the twentieth century, reproduce the necessity for codes and restriction. Through significant and underscored omissions, startling contradictions, heavily nuanced conflicts, through the way writers peopled their work with the signs and bodies of this presence–one can see that a real or fabricated Africanist presence was crucial to their sense of Americanness. And it shows.” (pages 5-6)

And, Qiana, let me know what you think of Reggie Byers’s work if you get a chance to take a look at it. I think there’s probably an essay to be written about how he helped to introduce the Japanese manga/anime style to American comics in the 1980s, especially in his series _Shuriken_ and his work on the Robotech comics for Comico. Aside from TV shows like Battle of the Planets and Voltron, Byers’s comics were my first exposure to anime and manga, before companies like First started to publish series like Lone Wolf in Cub in translation. His work is a lot of fun!

Hmm, the repeated references to lack of more stuff on Milestone that I have come across lately is making me move it up in my queue of things to get my hands on and read/write about.

I was able to assemble a complete run of Milestone comics pretty easily and cheaply: there are a lot of Milestone copies out there and frankly it doesn’t seem that many people are looking for them (or paying high prices for them). Since DC shows little interest in continuing to reprint them, this seems the only way to go.

Is anyone interested in sports comics featuring African Americans? There were short series devoted to Joe Louis, Jackie Robinson, and Willie Mays, presumably created by white writers and artists, but fascinating for the way in which they articulate black athletes as national heroes (if not superheroes) for white (and black?) audiences in the decade before the civil rights era.

Corey! I’m *very* interested in the sports comics. Especially the Jackie Robinson series. It’s really hard to find these. I was planning to look them up the next time I go to the archives at the Library of Congress or Michigan. Have you seen full issues?

Hasn’t the most popular of the Milestone characters (Static) made a reappearance in the DCU? There was also a cartoon devoted to him (Static Shock, it was called).

From the beginning of comic strips to the creation of comic books to the rise of graphic novels to now, I insist: there simply aren’t enough African American comics in existence to make any comprehensive or sweeping theories about “what” “African American comics” “are.”

The total number of African American cartoonists and comic writers is and has always been small. That becomes smaller when you consider that many forms of comics do not overlap. One doesn’t look at Charles Schulz and Steve Ditko and say “hmmm, I’ve got an idea about what white people are about,” because those two artists are extremely far from one another. A theorist would have to devise an absurd contrivance to directly link Schulz and Ditko. But the sample pool for white cartoonists is so vast that one needn’t contrive anything. Schulz can be compared to newspaper strip cartoonists from before his strip, at the time of his strip’s onset, throughout the run of his strip and after his death. Ditko can be compared to a long list of his contemporaries, antecedents and descendants.

When one considers African American comic-makers, one thinks of a few names in any particular family of comics (strips, comic books, graphic novels, webcomics, minicomics), and a few names at any given time (Jackie Ormes, Ray Billingsly, Aaron McGrudder, Kieth Knight).

But it is only a few. Are there a dozen syndicated African American cartoonists making strips? Are there even twelve?

There are hundreds of comic book artists in the superhero field. Are there a hundred African American comic book artists in superheroes? Are there two dozen?

There is approximately one (ONE!) African American writer currently working for DC or Marvel.

There are a handful of African American cartoonists making webcomics. I can count those that I am aware of on my fingers.

Yes, African American cartoonists are out there. Yes, we have always been out there. But the numbers are extremely low and with such a small figure to work with, one can’t make any reasonable analysis of what “African American comics mean.”

There are so few African American cartoonists and comic writers working in any particular branch of comics that any individual whim of a single person can probably be graphed as a double-digit percentage of “trend among African American comics.”

Ayo, how many African American cartoonists and comic writers do you think there should be before the subject is worthy of study?

I’m not so sure that you couldn’t find a fair bit of common ground between Schulz and Ditko. Anxious put upon man-boys seem like a common theme, and one possibly relatable to notions of specifically white male identity.

I have a couple of the Jackie Robinson comics: they aren’t just hard to find, but expensive because sports collectors are after them (as well as some comics collectors). They are probably the most significant of these because there were more of them than in the series for Joe Louis (only 2) and Willie Mays — but these figures were also featured in other “true sport” comics (or the short-lived NEGRO HEROES): what’s fascinating to me about them all is how sports facilitated the positive representation of African Americans — not just in comics, of course, but there too. Because the images of these figures were well known the drawings — while not especially distinguished by comics standards — can’t rely on the stereotypes that were still common in the period. I assume all of these fell out of copyright some time ago: someone should collect and reprint these.

Noah, this is where these large racial categories give me pause: it’s the reason for my hesitation around African American as a “generic” category. The whiteness that connects Ditko and Schulz overwhelms their differences — East Coast Jewishness and Midwest WASP values become obscured, and the differences between a daily kid strip and superhero comic books are overridden by shared gender and (spurious) racial connections? While something is revealed by viewing both as white, what is obscured?

Corey, any analysis will obscure something because you can’t talk about everything at once. And of course there are always differences as well as similarities.

Why do you feel the racial connection is spurious? I certainly haven’t formulated it entirely, but it seems to me that, keeping in mind Toni Morrison, white masculinity very often has an eye on black masculinity, and is in many ways constituted in opposition to it. The sense of white male victimization, of not being manly enough, exists in an American context where dangerous, violent masculinity is often marked as stereotypically black, while being “normal” and civilized, non-brutal and victimized, is stereotypically white.

And yes, of course, that isn’t the only thing to say about Schulz (whose work I love, as just one more thing to say) and Ditko (who I find sporadically appealing.) But why the particular anxiety that saying this one thing will prevent you from saying anything else? No one said, “once we use this lens, we’re never allowed to use any other lens ever,” I don’t think. I mean, in the (relatively brief) history of comics studies, wouldn’t it be much more true to say that differences in format have been emphasized at the expense of discussions of race? Like I said before, comics is really white compared to most other pop culture. This is not something I have really seen discussed at length, while conversations about production format and serialization seem relatively common.

I think that comics nostalgia (which certainly involves both Schulz and Ditko) has something to do with white identity, inasmuch as nostalgia for the past and childhood in these contexts tends to ignore black experiences (since the idealized past really was not ideal from that perspective.) This is actually something that Chris Ware engages with quite a bit, it seems like. Part of his work can be seen as thinking about the whiteness of comics in part in order to allow for, or un-erase, African-American experience.

If you prefer to think about production and format, I suspect that newspaper strips and comic books were more similar than different in their professional attitudes towards black creators. Which is to say, both industries were deliberately segregated, right? You didn’t end up with so few black creators by accident. Whiteness erased the differences between Ditko and Schulz at least as far as their access to being comics creators was concerned.

“Before the subject is worthy of study,”

You are sarcastic but I’m not playing with you. I didn’t say the subject is not worthy of study. I said that African American comics do not exist in the quantity where one can make any broad pronouncements about “what is one.”

I deeply regret spending any time on you or your article.

Come on, Darryl. You really think Qiana asking for clarification needs a line in the sand?

I know these issues are charged, but maybe folks could take a breath….

You’re right, I was being sarcastic. I should have just been honest and said what I was really thinking: Your comment bothered me because I believe you’re selling short hundreds of African American comics creators that have been involved in the industry from its beginnings in this country. But even if there was just one, the category would still be relevant.

I agree that making broad, uninformed pronouncements about trends and meaning is problematic. I don’t appreciate when people make assumptions about me based only on my race or gender, so I would never advocate doing the same to another person’s work of art. However the term “African American Comics” (or “Black Comics” or “Negro Comics”) is already in use. My question asked what kinds of comics should fall under the category and why. That’s it.

Finally got around to reading Priest’s intro to that Black Panther trade. . . oof. I don’t know. I mean, it makes me curious to read it, but it also makes me pretty sure I wouldn’t like it (the sample of art doesn’t help either).

Oh no, I really hope you decide to pick it up, Osvaldo. Priest makes some interesting modifications to the character in his attempt to avoid the pitfalls he describes in that intro. It would be great to compare his approach to the other black superheroes that you’ve analyzed.

I will. No worries – though I may try and find the Milestone comics first.

I am currently reading MacGregor’s much lauded run of Black Panther from Jungle Action in the 70s and not finding that much to like there – lots of it is deeply problematic. So far, aside from the art, the best I can say about it is that since it has a nearly all-black cast it allows there to be different personality types represented – but still, some of them. . .? Again, ooof.

The dialogue in Jungle Action is some of the most atrocious in comics history.BTW its main penciler, the late Billy Graham, was African-American. He also inked, and often penciled, Luke Cage Hero for Hire.

Check this exhibition out:

http://celebrity.yahoo.com/news/pa-exhibit-highlights-early-black-comic-artists-182451358.html

A bit late to the game, I suppose. But I wanted to throw in because this topic came up recently at our comics reading groups at the UO. We read MARCH, as well as the intro and afterward to the recent essay collection BLACK COMICS. I was happy to stumble across this piece, in part because it defends Black Panther and other such heroes where (the intro at least) BLACK COMICS wants to deny them as derivative and, largely, the imagination of white creators and therefore not really black comics…even though he is the first black superhero.

What’s interesting in this respect is that MARCH’s creative team is largely white–inspired by John Lewis’s story, working under and with him, adapting his memoirs-but still, Aydin and Powell are white. I was actually really impressed by the book and pleasantly surprised by its formal complexity, and I think few people would argue that the text provides a unique contribution to the literature about the civil rights movement and what it means to be black in America.

However, if Black Panther (in his original incarnations, not Priest’s) doesn’t count as “black comics” because two white dudes made it, couldn’t the same be said of MARCH, or does John Lewis’s involvement make the point moot? I want to make it clear that I am absolutely NOT arguing that categorizing “black comics” is a useless endeavor. I guess I am using a specific text to re-ask Qianna’s question.

I suppose that “black comics” are useful in the same way any kind of race/gender based literature is useful. It is a deeply flawed categorization, but it’s also necessary to make that move if we are to challenge the historical erasure of black comics creators and comics about black characters. It’s sort of like the Bechdel Test–necessary for challenging the systemic problem of Hollywood’s representation of women even if it sometimes fails as a test for feminism itself (ALIEN doesn’t pass, SEX & THE CITY 2 does)

Hi Andrea, thanks for stopping by. What I would give to be a part of the UO comics reading group!

Your question, the scenario you describe, is part of the reason why I wanted to talk about this topic. While the idea of the single creator as auteur may be appealing (and convenient) in drawing conclusions about determining the artistic and ideological vision of a story, we can see from this conversation that comics require a different framework. There are just so many hands involved! And so, the category becomes (for me, at least) useful as a starting place for analyzing a loose association of titles, characters, and creators. There has been enough work done that we can identify some trends and make informed observations about “black comics” and still delight in the way that writers/artists defy the category altogether.

I remember when “History Detectives” on PBS took a closer look at Negro Romance and there was this moment after the host reveals the identity of the uncredited white writer (Roy Ald) that she points out the artist was black: Alvin C. Hollingsworth. And in the clip, Gerald Early is surprised and really excited, and I’m watching this and I’m really excited too – I didn’t even know who Hollingsworth was! Early calls it “a genuine artifact of African American life, African American culture.” (You can see the transcript here, the quote is near the end: http://www-tc.pbs.org/opb/historydetectives/static/media/transcripts/2011-07-12/904_negroromance.pdf) It was an off-the-cuff remark, but I’m anxious to hear if he’s given any more thought to what it means that Hollingsworth’s presence makes a comic like Negro Romance more genuine. And…. does Nate Powell make March less so? Hmmm… this can get crazy… I’m much more comfortable claiming them both (and I think Early would agree with this).

Pingback: MARCH Discussion Recap | We Read Comics

On Hollingsworth:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alvin_Hollingsworth

Pingback: Charles Johnson’s “It’s life as I see it” and Single Panel Cartoons | The Funny Book Project