Fact: Women are problematically objectified in mainstream superhero comics.

This much is undeniable. And, to be blunt, inexcusable. But that doesn’t mean that it isn’t worth thinking about exactly how this objectification works (with an eye towards systematic attempts at educating readers about, and hopefully eliminating, the problematic aspects of such objectification, if nothing else).

This much is undeniable. And, to be blunt, inexcusable. But that doesn’t mean that it isn’t worth thinking about exactly how this objectification works (with an eye towards systematic attempts at educating readers about, and hopefully eliminating, the problematic aspects of such objectification, if nothing else).

Some might argue (and many misguided souls have tried) that males are also objectified in comics, insofar as overly exaggerated, hypersexualized depictions are as much the norm for male superheroes as they are for females. This is true, but it misses an important point: unrealistic depictions of male anatomy and garb in superhero comics plays a very different role than analogous distortions of female anatomy and clothing.

I am not going to try to sort out the differences between how males and females are depicted in comics here (it is sometime said that the difference is that superheroes are drawn the way that adolescent readers of comics want to be, and that superheroines are drawn the way that adolescent readers of comics want their girlfriends to be – this seems like a stab in the right direction, but it is both too simplistic and ignores the fact that the readership of superhero comics is much wider than the basement-dwelling, maladjusted adolescent males that the explanation seems to rely on). What I am going to do is highlight an interesting sub-phenomenon – superheroines whose hypersexualization is linked to their very real (albeit fictional) power as superheroines.

Here is one natural thought about hypersexualized depictions in general, and of superheroines in particular: Such emphasis on, and exaggeration of, secondary sexual characteristics such as breast size and waist-to-hip ratio serves to rob female characters of power. In emphasizing the superheroine’s role as a potential, and exaggeratedly desirable, partner for the male characters in the narrative (and, indirectly, for the reader), the superheroine in question is reduced to an object to be possessed, rather than a subject with her own autonomous agency and efficacy. As a result, the superheroine – super-powered or not – is rendered relatively powerless and hence relatively unthreatening to the male-dominated (both the characters and their fans) world of mainstream superhero comics.

Here is one natural thought about hypersexualized depictions in general, and of superheroines in particular: Such emphasis on, and exaggeration of, secondary sexual characteristics such as breast size and waist-to-hip ratio serves to rob female characters of power. In emphasizing the superheroine’s role as a potential, and exaggeratedly desirable, partner for the male characters in the narrative (and, indirectly, for the reader), the superheroine in question is reduced to an object to be possessed, rather than a subject with her own autonomous agency and efficacy. As a result, the superheroine – super-powered or not – is rendered relatively powerless and hence relatively unthreatening to the male-dominated (both the characters and their fans) world of mainstream superhero comics.

Now, this is, to be honest, a bit too quick. After all, the objectifying sexualization of female characters in comics can serve to emphasize a superheroine’s sexual power (although this strategy is most often applied to villainesses, since female sexual power is conventionally troped as threatening and hence evil). But sexual power – especially female sexual power – is typically treated as somehow deviant compared to the kinds of physical, economic, political, and social power typically associated with, and monopolized by, males. So the analysis of devaluing and/or rendering harmless via hypersexualization still applies.

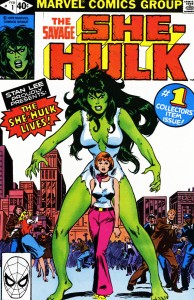

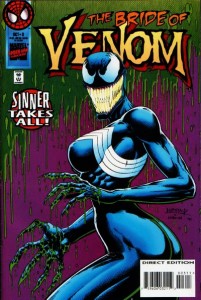

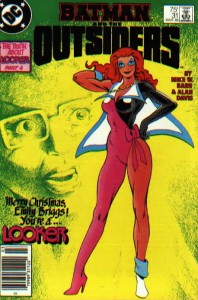

There is no doubt that the far-too-common depictions of superheroines as super-endowed, scantily clad supermodels whose primary role is to be saved by, avenged by, or romanced by their superhero compatriots has played exactly this role in the past. But there are a handful of female characters whose depictions throw a complicating monkey-wrench into the mix. I have in mind those characters whose transformations into their superpowered forms also involve physical transformations from more realistic (relatively speaking) depictions to the sort of unrealistic, hypersexualized forms at issue here. Prominent examples include the She-Hulk and the Red She-Hulk (whose transformations from human form to ‘hulked-out’ form also involve dramatic alterations to relative breast size, waist-to-hip ratio, etc.) Mary Marvel (whose transformation upon uttering “Shazam” involves morphing from a teenage girl to a mature woman), Looker (whose acquisition of superpowers also involved substantial ‘positive’ changes in her physical appearance), Titania, the Bulleteer, any female Marvel character who has interacted with any version of the Venom symbiote, etc. etc.

There is no doubt that the far-too-common depictions of superheroines as super-endowed, scantily clad supermodels whose primary role is to be saved by, avenged by, or romanced by their superhero compatriots has played exactly this role in the past. But there are a handful of female characters whose depictions throw a complicating monkey-wrench into the mix. I have in mind those characters whose transformations into their superpowered forms also involve physical transformations from more realistic (relatively speaking) depictions to the sort of unrealistic, hypersexualized forms at issue here. Prominent examples include the She-Hulk and the Red She-Hulk (whose transformations from human form to ‘hulked-out’ form also involve dramatic alterations to relative breast size, waist-to-hip ratio, etc.) Mary Marvel (whose transformation upon uttering “Shazam” involves morphing from a teenage girl to a mature woman), Looker (whose acquisition of superpowers also involved substantial ‘positive’ changes in her physical appearance), Titania, the Bulleteer, any female Marvel character who has interacted with any version of the Venom symbiote, etc. etc.

In all these cases, the acquisition of superpowers is explicitly associated with a change in appearance, from (again, relatively speaking) roughly realistic anatomy and habits of dress to explicitly sexualized, overly exaggerated forms (and, in many of these cases, there is also a marked increase in confidence and authority). As a result, it is hard to square these cases with the analysis just given of hypersexualization as a means to strip female comic book characters of power, since in these cases exaggerated anatomy and revealing clothing are explicitly associated with the acquisition of power.

As a result, we are left wanting an analysis of how, exactly, hypersexualized depiction of these characters works (especially with regard to the sorts of power these characters are depicted as having, and actually have, within the fictional narratives in question). Is it possible that these female characters somehow destabilize the status quo with regard to depictions of females, and thus represent some sort of subversive interrogation of gender roles and power in comics (intentional or not)? Are they just as worrisome as more ‘traditional’ hypersexualized depictions of female superheroes, regardless of whether they complicate our understanding of the relation between sexual objectification and power? Is this merely just a strange little quirk, unimportant in comparison to the more straightforward, and sadly extremely common, objectification found in mainstream superhero comics?

As a result, we are left wanting an analysis of how, exactly, hypersexualized depiction of these characters works (especially with regard to the sorts of power these characters are depicted as having, and actually have, within the fictional narratives in question). Is it possible that these female characters somehow destabilize the status quo with regard to depictions of females, and thus represent some sort of subversive interrogation of gender roles and power in comics (intentional or not)? Are they just as worrisome as more ‘traditional’ hypersexualized depictions of female superheroes, regardless of whether they complicate our understanding of the relation between sexual objectification and power? Is this merely just a strange little quirk, unimportant in comparison to the more straightforward, and sadly extremely common, objectification found in mainstream superhero comics?

So how do hypersexualized superhero transformations work?

So this is a really interesting question. I don’t think superheroine obectification has to to with trying to diminish female power exactly, though. I’d say that instead there’s just a tendency to see women primarily or entirely as sexual beings, therefore extraordinary women would be extraordinarily sexual.

Along those lines, there is something to the idea that men are also sexualized. The difference is that male sexuality is seen as active and strong, whereas female sexuality is seen as being a porn star. The sexism comes in not because women are sexualized, but because under sexism female sexualization is only in terms of objectification, as opposed to male sexualization, which involves action and power.

I think the transformation doesn’t really change that dynamic. Though I think that, just as there’s a charge in seeing plain guy transform into powerful superman, there’s a charge for the male audience in imagining that buttoned up, plain girl over there suddenly transforming in into hypersexual cheesecake.

Finally, it’s worth remembering that male investment in female objectification can be masochistic as well as sadistic. Powerful women are a thing for lots of guys (Frank Miller, we’re looking at you.) Masochism can be intertwined with feminism in certain ways (this is the argument for the noir bitch being at least a provisionally feminist figure) but it doesn’t have to be.

I’m not convinced there’s anything particularly sexual about that Mary Marvel image…

Mary Marvel traditionally has a very “girl scout” personality. If a girl scout has unusually large breasts, she may be treated differently by people around her, but that’s not her issue, it’s the baggage other people bring to her body shape…

Sorry to not address you exact question. But to show how far — or not — this conversation has come, I am put in mind of a 1980 Comics Journal interview with John Byrne, who is asked by one “Gretchen Finke” why all the women in comics are “so . . . healthy.” Byrne’s answer: “Because the guys are too. Does that bother you?” Phoenix has big boobs because Colossus has big boobs. And for the rest of the exchange, Byrne and co. talk about how important it is to draw good boobs, how some artists draw bad boobs, how Carmine Infantino draws banana boobs.

Gretchen never speaks again.

Pallas, the point is though that she goes from not being sexualized as a civilian to being sexualized as a superhero (and bigger breasts reads as sexualized — and remember, this isn’t a real person, someone drew her.)

I think it’s reasonable to point out that MM has traditionally been less sexualized than a character like She-Hulk (though that changed in one of the recent iterations where she became evil, right?)

Can’t help but think of Chris Ware’s sexualized sketchbook parody of Mary Marvel and the Marvel Family from the cover of WOW COMICS #9.

Superhero comics play “strong and active” for sex appeal with female characters, also — or at least they always have with She-Hulk. Could some of this just be the same fan wish fulfillment at play with the male characters? Billy Batson gets to be a handsome man, Mary Batson gets to be a beautiful woman, and Jennifer Walters gets to be tall and buxom and brash. This is the second time I’ve mentioned the new Ms. Marvel in ten minutes, but they’re addressing the hypersexualized transformation issue directly there. The protagonist gets the transformation she wished for, then changes her mind and her form.

“Pallas, the point is though that she goes from not being sexualized as a civilian to being sexualized ”

I think you missed my point. You have to prove she’s sexualized before you can say she’s sexualized.

So how is she sexualized? She has large breasts appears to be the argument. I’m questioning that.

” and remember, this isn’t a real person, someone drew her.”

And you should remember their are real people in the world with large breasts. If a woman with large breasts read the argument that character with large breasts= sexualized, do you think she might take issues with what the critic is implying about her own body? (Hypothetically)

I’m thinking about this because I just read this article “By Boobs, my Burden at Salon” http://www.salon.com/2014/02/24/my_boobs_my_burden_partner/

The author describes conversations with a mom and daughter related to her breast size:

“Leah also remembers her mother being critical of her breasts. “I had these shirts I really liked from the juniors department (where I quickly realized I could not shop)—made out of this stretchy, sparkly material, and I was a very small, skinny girl who just happened to develop big boobs.” And it would be like a sitcom: her mother would say, “‘You get right back upstairs young lady, you’re not leaving the house dressed like that.’ And I didn’t understand why,” Leah said. “I was like, ‘Mom, it doesn’t mean anything, it’s just the way my body stretches out the clothes.’” Her mother would say, “‘It makes you look like you’re asking for it, it makes you look like a slut’—I don’t know if she said those words exactly but that’s how I remember it,” Leah said. “It made me feel like I was concealing something very dangerous and bad.””

I’m not sure what comic that Mary Marvel image is from, but I assume its before the recent changes when she became a villain when she was still depicted as a sort of ultimate girl scout.

Some of these tropes depend upon American readings, by the way. Clotaire Rapaille’s book The Culture Code talks about how the American “code” for beauty is man’s salvation, the code for sex is violence, and the code for seduction is manipulation. This puts the American woman, like the Salon author above, in a difficult situation. She has a responsible to be beautiful, but being alluring can be dangerous, and being seductive can be seen as downright evil.

Mary Marvel is a complicated, but maybe perfect, example for this topic. DC portrayed her, and sometimes her brother, as paragons of innocence for years. Then they infected Mary with some kind of evil. I’ve successfully blocked out most of the storyline, so it’s hard to remember. Anyway, she immediately became more overtly sexual (see Culture Code reference above). I think this was during the early days of the Dan Didio / Geoff johns regime, and perhaps part of their effort to turn their comics into what Mark Waid has called “fanboy torture porn.”

Pallas, I read that Salon article too. And yes, real people have large breasts. But part of what the Salon writer is saying is that having large breasts makes her insistently sexualized. People treat her as a sexual object (men and women both). Creating a character whose cup size balloons is therefore a move to sexualize her. There are ways you could get around that. The comic could discuss problems with large breast size, could have Mary’s costume be looser so it didn’t emphasize her top…or could even have her breast size be the same in both forms, rather than seeing it as a superpower to have bigger breasts.As it is, though, I think the breasts are supposed to signal what big breasts are default supposed to signal.

Also…you know that innocence is sexualized for women too, right? I think it’s true that MM has been less sexualized as a character than some, but the fact that she’s a girl scout doesn’t mean she’s not fetishized, or can’t be fetishized. On the contrary.

That Ms. Marvel comic sounds great. I need to get that.

Terrific question, Roy. I’m wondering – sort of along the lines of Pallas’ question – doesn’t it matter if or how the sexualization plays out in these stories? What the physical transformation actually enables? Does it grant particular kinds of access, generate obstacles, attract/repel specific kinds of attention that is relevant to the story… Or is the spectacle mostly for the benefit of the comics reader who is supposed to make assumptions about her power/desirability based on physical appearance… I’m only really familiar with She-Hulk and it seems like in trying to balance her character’s strength with her femininity, the artists try all sorts of configurations with her lawyer clothes and the body suit, etc. with uneven results.

The Steve Englehart run on Fantastic Four in the late ’80s did play around with this issue. That run was a hot mess in general, but it did introduce the character of Sharon ventura, who starts out as “Ms. Marvel,” your comics-typical hot-babe-who-can-kick-ass, but later mutates into a female version of Ben Grimm, the Thing.

I always thought this was Englehart’s commentary on the She-Hulk: the female “counterpart” to the monster, who, rather than being equally hideous, became a male fantasy figure. Only Englehart did in fact make her equally as hideous as the Thing.

Too equally, in my opinion. She was literally drawn as Ben Grimm, only with breasts, which reduced from being her own character to a parody of another. She was pretty much reviled by fanboys everywhere as I recall. I’ve often thought that if she had her own uniquely monstrous design, she could have been seen more as her own character, and Englehart’s point might not have been so obscured. But then, knowing fanboys, they probably would have responded the same way.

(I do think Englehart was baiting the fanboys, though. One Annual featured a pin-up section, and the selection for Ms. Marvel had her striking a full-on cheesecake pose, in full-on “She-Thing” mode, as if to say “deal with it, guys.”)

Later in the run, Ben Grimm was cured of being the Thing, but (having been on the other side of the monster-human relationship for so long) actively continued his boyfriend-girlfriend relationship with Sharon ventura while she was still Thing-ed up.

These stories don’t really add up to more than an interesting blip, but Englehart was sort of planting a flag here for unconventional body types & relationships.

I think narrative matters a lot. In the Marston/Peter WW, erotic spectacle is deliberately presented as an alternative to violence. It’s also deliberately presented as erotic spectacle for both girls and boys, both in the sense that lesbianism is a conscious possibility in the stories, and in the sense that there’s a fair bit of beefcake (also for both girls and boys, presumably.)

“or could even have her breast size be the same in both forms, –

Traditionally, the character goes from a child to an adult. (I’m not sure what was going in that image in terms of age transformation) I don’t think its a stretch to say that breasts are also associated with adulthood.

I don’t know, your argument strikes me as problematic. Nobody expects Stan Lee to “justify” Spider-man’s body by talking about the discomforts of fighting crime in tights while sporting an erection.

But apparently something like this needs to be done with a big breasted character to “justify” the body shape… it just strikes me as a little odd.

Interesting questions, Roy! It’s also worth noting, as an aside, that C.C. Beck wrote several essays for the fan press about his discomfort with the more realistic depiction of the Marvel Family that DC gradually introduced after the company revived these properties in the 1970s (originally with Beck as the artist, before he left Shazam! out of frustration over the scripts).

Beck, in fact, had something of a falling out with artist Don Newton over Newton’s depiction of the characters. Although Beck had been a mentor to the younger artist, Newton’s style was much closer to Neal Adams or John Buscema than to Beck’s work. You can read more about their disagreement here:

http://www.donnewton.com/ccbeck.asp

In the Fawcett era, Mary, Billy Batson’s long-lost sister, is just as much a paragon of virtue as he is, the ideal American girl to match her brother, the idealized American boy. But Otto Binder and Marc Swayze’s Mary Marvel bears little resemblance to DC’s later version of the character, not least because in the original stories, unlike her brother, she and Freddy Freeman are still kids when they speak their magic words. Only her brother becomes an adult–or, anyway, looks like an adult (although, as Otto Binder often suggested, Billy was usually a lot smarter and more cunning than Captain Marvel, a telling inversion of the usually superhero transformation story).

About innocence being sexualized–I always think these superheroines were considerably sexier before they were drawn as porn stars and strippers. I mean, Supergirl in the early 60s was a pretty blonde girl flying around in a short skirt and boots. On the old Batman t.v. show, Catwoman was a beautiful woman who went around taunting and tying up the square male heroes. That seems like more than enough for pubescent boys to fantasize about–adding massive t&a and raunchy poses just reminds you that creepy, adult, male weirdos are drawing this stuff.

Sorry if I’ve brought down the level of yet another discussion.

Pallas, I’m arguing that Spider-Man with those tights and crotch-shots is sexualized too. Sexualization just works differently for men and women. But the difference is in the treatment/presentation of what sexuality is by gender, not in the fact that sexualization is occurring. (Or at least, that’s what I’m arguing.)

I think narrative context matters. While folks like Pallas want to argue that there is no inherent sexualization of these female characters going on, the arguments don’t hold water. I can’t imagine it being anymore explicit. Even if you could prove that an artist draws a female superheroine with bigger breasts, etc… “just because” it would not change the meaning of that transformation in regards to the context of depicting hyper-sexual appeal.

Heck, even depictions of “innocence” only work because of an unspoken appeal to salaciousness and to the possibility of despoiled innocence.

Anyway, given the baseline of this kind of depiction like I said narrative context matters. For example, when I wrote about She-Hulk a few months ago, I tried to show how Slott addressed the double-standards of her sexuality and the possibility of her empowerment through sexual agency in that run and to craft a narrative from the problematic nature of the fantasy of male desire regarding female agency (though the lothario Starfox living roofie arc). It didn’t work perfectly, but like I said, given the reality of how these female characters are depicted the question should be, what is to be done with it? What “fixes” it? How can the relation to it be flipped in the narratives to create more possibilities? Or does it always fall back into the trap of enacting exactly what it seeks to comment upon?

Interesting. A few thoughts:

i) You’re giving the “artists” a bit too much credit in searching for a thematic “role” that hyper-sexualisation plays. The reasons for HS, I submit, are primarily extra-diegetic, including:

1) the tastes of the perceived audience. On this point, your claim that “the readership of superhero comics is much wider than the basement-dwelling, maladjusted adolescent males that the explanation seems to rely on” is misleading. The fact that the demographic of superhero comics readers is broader than the stereotype is completely compatible with the artists/companies nonetheless pandering to what they see as their target demographic

2) Relatedly, the tastes of the “artists” in question. How many HS-ing artists are fans-turned-pro? 90% (to pull a figure out of my arse)? 95% As far as they’re concerned, that’s just how superwomen are supposed to look, because that’s how they looked in the Image style of the 90s. The continued prevalence of HS has a lot to do with this kind of self-sustaining feedback loop (although, granted, that doesn’t explain why it emerged in the first place).

3) The rise of the market for “original” superhero “art” pages. I think a couple of the vices of current superhero comics can be traced to this — the proliferation of pointless splash-pages (tho that’s also due to the laziness of the artists and their struggles to hit deadlines), and of iconic “moments” (to use a term from Tim O’Neill). And so it goes for HS, too — again, they’re pandering to the perceived demographic and, mind-boggling to me as it is, that’s what the perceived demographic wants.

ii) All that said, there is an interesting thematic role for what you might call super-hypersexualisation — HS that goes beyond the direct physical attributes to, let’s face it, slutify (sic) either supervillainesses or superheroines who undergo heel turns. I’m thinking, for instance, of how Claremont and Byrne signal Phoenix’ evil tendencies through her wardrobe (in the Hellfire sequence) and general sexual appetite; or Claremont again and Silvestri with Madelyne Pryor’s heel turn (tho’ god bless them for doing the same to male character Havoc); or how Morrison and Jones signal Mary Marvel’s heel turn by giving her a boob window and thigh-high boots. Now, that’s an area where there really is a diegetic point to the SHS, where women’s sexual power is coded as dangerous

iii) The question isn’t really so much why superheroine transformation is HS-ed, as why the civilian, non-powered forms are not HSed. HS is not some artistic deviation from the norm that needs to be explained; rather, what needs to be explained is why Jennifer Walters is so (from the visual perspective of genre conventions) mousy/un-“hot”. And there, again, is where thematic considerations do play a role.

‘I think narrative context matters. While folks like Pallas want to argue that there is no inherent sexualization of these female characters going on, the arguments don’t hold water. I can’t imagine it being anymore explicit.”

You can’t imagine it being any more explicit, really? So if hard core porn is a 10 in the level of explicit sexuality, on a scale of 1 to 10, that’s exactly where you see these comics?

It’s all pornography, pornography, pornography, to you?

Please don’t lump me in with whatever imagined group of straw men you have in mind by saying things like “folks like Pallas”.

I never mentioned She Hulk- or any other character than Mary Marvel. Female characters are not interchangeable blurs to me.

Wow – I clearly stirred things up a bit with this one.

There’s no way I am going to be able to address all of these comments (even all the ones directed at me), so I’ll just make some quick observations.

First, I think it is important to note that the kind of hypersexualization going on with She-Hulk and others of her ilk (ulk?) is quite different from what is going on with Mary Marvel. But there is no doubt that the post-transformation superheroines in both cases are sexualized when compared to their pre-transformation forms. In the case of the She-Hulk, it is from ‘realistic’ proportions to hyper-exaggerated (in a sexualized, breast size, waist-hip ration, etc. manner) form. With Mary Marvel, it is something different – she transforms from a teenage (read: innocent, pre-sexual) form to an adult, mature (read: sexual) form. So, although one might worry about whether the term “hypersexualized” applies to the post transformation Mary Marvel, that form is clearly sexualized to a great degree when compared to her pre-transformation appearance (in short, post-transformation she is fair game as an object of desire, but pre-transformation she is not, which is creepy since her actual chronological age does not change.)

Second, I think Jones hit on an important point: It is not that the post-transformation form of the She-Hulk is more sexualized than other female superheroes who lack this transformation aspect. It is that their pre-transformation forms are notably less sexualized (often both in terms of appearance and characterization). So then the question really is not about the hypersexualization itself, but rather the role that the transformation from less to more sexualized plays.

No, Pallas, it is not all pornography to me. There is clearly a range of representing sexualization – but while the Mary Marvel transformation may be on the low end it is no less explicit in how it represents her “womanliness” through her secondary sex characteristic and its appeal to a notion of innocence that can only function in relation to potential sexiness.

I am sorry if I lumped you in with other people, you just struck me as arguing very disingenuously as if Mary Marvel could _only_ be sexualized if she was depicted like She-Hulk.

So…I don’t think Pallas is being disingenuous and I don’t think Osvaldo was trying to strawman anyone…maybe folks could take a breath?

“I can’t imagine it being anymore explicit.”

http://tinyurl.com/muyjnmn

http://tinyurl.com/ou86mnr

http://tinyurl.com/lqp65ru

http://tinyurl.com/lhtvq3d

http://tinyurl.com/ku94jo2

Try to imagine that contemporary superhero comics are as gross as possible — however gross you’ve imagined, that’s not gross enough.

I appreciate one of John Hennings’ comments in particular:

“Some of these tropes depend upon American readings, by the way. Clotaire Rapaille’s book The Culture Code talks about how the American “code” for beauty is man’s salvation, the code for sex is violence, and the code for seduction is manipulation. This puts the American woman, like the Salon author above, in a difficult situation. She has a responsible to be beautiful, but being alluring can be dangerous, and being seductive can be seen as downright evil.”

This makes the case of She-Hulk very interesting. If it’s her responsibility (pre-transformation) to be beautiful, then her responsibility (post-transformation) becomes fraught: her hypersexual attraction makes her dangerous/downright evil? In this case, then, it seems that the visual representation of HS allure struggles against the narratively constructed goodness of her character. Like Qiana, I have a familiarity with She-Hulk but not a lot of deep reading experience, so I don’t know how far to go with this line of inquiry. But maybe Roy can answer this: does She-Hulk in some sense uniquely embody the competing Discourses of femininity, female sexuality, and power? After all, as you point out, the visual transformation goes from less sexualized to more sexualized. The visual transformation also goes from less physical strength/power to more physical strength/power. Does that reflect something in her character, too? If the code for sex is violence, then does She-Hulk’s physical strength then index more sexuality? If the code for seduction is manipulation, where does that leave us with She-Hulk?

Male superheroes who transform gain an appearance of physical power – not just strenght. This is shown as secondary sexual male traits (muscles) and behavior (confidence/arrogance, violence etc).

Roy is right in that, in the past, the pretty super heroines only role was to be rescued by their peers. However, how to represent this power fantasy, physically, if not by granting them secondary sexual traits?

If no one ever drawed them as that, comic drawers would be accused of not empowering them enough. They’d be accused of being moralistic, or puritan, avoiding to draw super heroine’s secondary sexual traits while the Hulk and Shazam are obviously much more manly then their civil identities.

I agree that super heroines are objectified – I mean, look at the way their clothes are drawn – but I disagree with the thesis that transformation is part of the issue here. Is there a single transforming male super hero who isn’t ‘sexualized’ somehow? Even Promethea is hotter than any of her civil identities. Super heroes are greek gods, of course they’re more beautiful than mundane people.

About villainnesses being more sexualized: this isn’t about female sexuality being dangerous. It’s about female malice being hot. Which is both sexist and immoral in its on way, but it doesn’t happen because writers are afraid of liberated women, it’s because we, writers and readers, are sometimes ambiguously attracted by evil. Male anti-heroes are also a focus of escapist fantasies because they’re violent and unbound by rules. Villains are anti-social; this means having less empathy, but also caring less about social norms about honor and sexuality.

Frank, the Dan Slott run of She-Hulk at least does tie her physical transformation to a sexual proclivity in a very direct way (at one point they compare the number of sexual partners she’s had as Jennifer Walters (around 3 or 4) as compared to her She-Hulk guise (innumerable!) Again, see my piece on it here on HU (link in my first comment).

Jones,

Perhaps I overstated/misstated – I didn’t mean that I couldn’t imagine it any more sexually explicit (of course, I could), I meant explicit as in obvious and clearly notable. I was commenting that her transformation from demure covered up nearly latent young teen girl into her superhero form with short skirt, bigger boobs, look of anticipation is a clear example of her being sexualized – i was not making an argument about the _degree_ to which she is being sexualized as compared to someone like She-Hulk or Lady Death or whoever.

Frank:

As Osvaldo put it (although he said it more modestly) – a great place to begin if one wants to think further about the She-Hulk with respect to how all this works is his essay here:

https://www.hoodedutilitarian.com/2013/11/dan-slotts-she-hulk-derivative-character-as-meta-comic/

As he notes, explicit differences in her personality pre- and post-transformation are noted (although some ambiguity is retained regarding whether the transformation has a direct effect on her personality (presumably in some way connected to, but distinctly different from, the way that the Hulk’s transformation is explicitly linked to anger), or whether the perceived differences in personality are a result of her feeling more confident and assertive in her more glamorous, more powerful form.

The new She-Hulk series (just begun a few weeks ago) might be interesting in this respect, since (based solely on the first issue) it seems to be focusing more on her role as lawyer (and more generally, her role in non-superhuman domains) than previous series (even Slott’s). But that might just be a quirk of the first issue – we shall see.

Am arriving late to this fascinating conversation but I also wonder if some of you have been operating under the assumption that hypersexualization makes female characters more available to (putatively adolescent male) readerships as sexual objects. Roy’s post suggested to me that it may in fact be the opposite. Although I also agree that we need to look at how hypersexualization fits into individual narratives, and that it signifies differently in different contexts, it still might be useful to shift the emphasis away from comic book representations of sexualized bodies in order to think about the readership Roy mentions. How do comic book representations of gendered bodies inform these readers’ transition into “adult” sexuality? Hypersexualized female (and male) characters are not good transitional objects. If anything they are the obstacles, alibis for the postponement of normative “adult” sexuality (and in this sense potentially queer). Consider, as a counterpoint, the example of yaoi representations of male homosexuality, which are so hugely popular because they present a version of male sexuality that is more accessible to adolescent girls who might otherwise feel blocked from access to the hypermasculine sexuality that appears in other quarters of Japanese cultural production. Yaoi masculinity, in its refusal of bodily difference, is successful as a transitional object for an adolescent readership. Hypersexualized comic book femininity, not so much.

The thing is, target audience for these representations certainly is not adolescent males now. Average age of superhero comic book readers is in the 20s and 30s I believe, right?

I’m not sure why hypersexualized images of women would be offputting for adolescent boys, though. Doesn’t seem like it would be necessarily.

Not offputting so much as inaccessible, frightening. Still sexual but maybe too sexual for a young person new to sexuality. (I’m picturing an adolescent boy faced with a naked Kim Kardashian, is that wrong?). Anyhow, my argument might have made sense during my own adolescence in the late 80s and early 90s but doesn’t hold water today, as you point out, Noah. Still, I do think that yaoi give us a fascinating angle for thinking about adolescent readerships and sexual development. And I want to insist that boys and girls aren’t that different, at the end of the day. Adolescent boys can be just as terrified by adult sexuality as girls, even though we don’t usually think so.

Maybe I’ll write my next post on yaoi as a follow-up to Albert’s, which I’m still savoring.