Is anyone else tired of superhero movies?

According New York Times reviewer A. O. Scott, superheroes peaked with The Dark Knight in 2008. Since then, “the genre, though it is still in a period of commercial ascendancy, has also entered a phase of imaginative decadence.” Scott said that back in 2012, before the release of Amazing Spider-Man, Iron Man 3, The Wolverine, Man of Steel, Kick-Ass 2, Dark Knight Rises, and Thor: The Dark World —much less the still future releases of X-Men: Days of Future Past, Amazing Spider-Man 2, Captain America: The Winter Soldier, Guardians of the Galaxy, The Avengers: Age of Ultron, Fantastic Four, and Batman vs. Superman.

Which is to say, he’s got a real point. All those masks and capes and inevitable act three slugfests—could we maybe call a moratorium while the screenwriters guild brainstorms new action tropes? I’m probably too optimistic that Edgar Wright’s 2015 Ant-Man will provide a much needed counterpunch to all the BAM! and POW!—the same way his 2004 Shaun of the Dead enlivened the weary corpse of the zombie movie (another genre still in decadent ascendance).

But instead of looking forward, maybe we should be looking backwards. If, like me, you crave a beer chaser for all those syrupy shots of Hollywood superheroism, tell your online bartender to stream some mid-twentieth century French avant-garde instead.

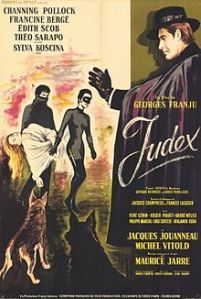

Georges Franju’s 1963 Judex has to be the least superheroic superhero movie ever made. Well into its third act, the title character (think Batman with a hat instead of pointy ears) bursts through a window to assail his enemies—only to allow one to step around him, pluck a conveniently placed brick from the floor, and sock him unconscious from behind. It’s not even a fight sequence. Everyone but the brick basher moves in a languid shuffle. The scene is one of many reasons critics label the film “dream-like,” “surreal,”“anti-logical,” “drowsy”—terms opposed to the adrenaline-thumping norms of the genre.

The original 1916 Judex, a silent serial by fellow French director Louis Feuillade, largely invented movie superheroes. The black cloaked “Judge” swears to avenge his dead father, leading to dozens of similarly cloaked avengers swooping in and out of the 20s and 30s. Judex had barely exited American theaters before film star Douglass Fairbanks was skimming issues of All-Story for his own pulp hero to adapt. A year later, the Judex-inspired Zorro was an international icon.

But Georges Franju was no Judex fan. He preferred Feuillade’s Fantomas, one of the most influential serials in screen and pulp history, and the reason Feuillade dreamed up his crime-fighter in the first place. Fantomas was a supervillain, as was Irma Vep in Feuillade’s equally popular Les Vampires, and French critics had grown weary of glorified crime. Fifty years later, Franju was still glorifying it, making one of France’s first horror films, Eyes Without a Face.

Feuillade’s grandson, Jacques Champreux, was a Franju fan—though he really should have checked the director’s other references before asking him to shoot a remake of the superhero ur-film. When the French government commissioned a documentary celebrating industrial modernization, Franju had focused on the filth spewing from French factories. When the slow-to-learn government commissioned a tribute to their War Museum, Franju used it as an opportunity to denounce militarism. Little wonder his Judex is a testament against the glorification of superheroism.

But Champreux bares some of the unintended credit too. Franju admitted to not having “the story writing gift,” but few of Feuillade’s gifts passed to Champreux either. Much of the remake’s surrealism is a result of inexplicable scripting. Champreux and fellow adapter Francis Lacassin boiled down the original five-hour serial to under a hundred minutes. While the streamlining is initially effective (opening with the corrupt banker reading Judex’s threatening letter is great), it soon creates much of that surreal illogic critics so praise:

Why is the detective so incompetent? (Because this is his first job after inheriting the detective agency.)

Why is the banker suddenly in love with his granddaughter’s governess? (Feuillade’s opening scene establishes her plot to seduce him and steal his money.)

Why set up the daughter’s engagement if her fiancé exits after one scene? (Because he originally returned as a villain in league with the governess.)

How does the detective’s never-before-mentioned girlfriend happen to find him just as she’s needed to aid Judex? (Feuillade introduced her well before, and the two were already walking together when Judex allows himself to be captured.)

How is Judex able to pose as the banker’s most trusted employee? (He took a job as a bank clerk years earlier and worked his way into the top position.)

Why is Judex even doing any of this? (His father committed suicide after the banker destroyed the family fortune and his mother made him vow to avenge his death.)

Some of Franju’s most pleasantly peculiar moments— the travelling circus that wanders past the bad guys’ hideout, the dog that appears from nowhere and sets his paw protectively on the fallen damsel’s body—are orphans from Feuillade’s plundered subplots. The remake is a highlight reel. Though, to be fair, not all of the surrealism is the result of the glitchy script.

By moving Judex’s death threat to midnight and shooting the engagement banquet as a masked ball, Franju offers the best Poe adaptation I’ve ever seen—even if all the bird costumes make it more of a Masque of the Avian Flu. And the Franju’s one fight scene isn’t derived from Feuillade at all. Originally the detective’s girlfriend attempts to save the governess who drowns while trying to escape, but Franju costumes the two women in opposite, if equally skintight attire—a proto-Catwoman vs. a white leotarded acrobat—before sending them to the roof to leg wrestle.

Instead of washing ashore in the epilogue, the governess falls to her death in a bed of flowers. Meanwhile, what’s Judex up to? Not only is the nominal hero not present for the vanquishing of the villainess, but by the end of the film he’s devolved into Douglass Fairbanks’ Don Diego, Zorro’s mild-mannered alter ego. While Franju was imitating the style of early cinema (yes, his version opens with a classic iris-out, a fun gimmick even though Feuillade avoided it in his own Judex), he also grafted Fairbanks’ goofy handkerchief magic into Judex’s less-than-superheroic repertoire. The tricks were cute in The Mark of Zorro, but once again inexplicable in the contemporary context.

And I mean that as praise. A Judex redux is exactly what the genre needs right now. I would love to watch Emma Stone toss the Lizard from a skyscraper while Spider-Man practices his web sculpting—or Natalie Portman shove a Dark Elf through a magic portal while Thor perfects a hammer juggling trick. Superhero films feature plenty of glitchy illogic, but it’s time for drowsy surrealism too. Why hasn’t Marvel or DC handed any directing reins to David Lynch yet? Or David Cronenberg? Terry Gilliam dodged The Watchmen back in the late 80s—but surely his version would have been more memorable than Zack Snyder’s. Isn’t there someone out there who can prove A. O. Scott wrong?

I think I actually enjoyed Franju’s Judex more than Feuillade’s. Can’t be sure whether this is down to watching the Franju version first. Neither of them are as good as Feuillade’s Les Vampires though.

Stay tuned! I’m working on a Les Vampires post too. (And, yes, definitely better than Judex.)

For Judex and Les Abysses, Francine Berge is one of my favourite actresses, though it seems sadly that she never got to star as the bad girl in anything else after that.