Like most nerds, I communicate primarily in quotes from The Simpsons, but I’m old enough that Bloom County makes it into the rotation from time to time. Nary a San Diego Comic-Con can pass, for example, without a Superman comic or “My Little Pony” display triggering me to say to my husband, “The Truth, Steve, is that ‘Knight Rider’ is actually a children’s program.” (The correct response: “Can’t be! Can’t *@#!* be!!”)

When Bloom County debuted, it was criticized, often rightly so, for lifting from Garry Trudeau’s Doonesbury. Breathed’s loose, doodle-y early style was a slightly more polished version of Trudeau’s; he later developed into one of the most skilled illustrators on the comics page, more reminiscent of Chuck Jones than any newspaper cartoonist, but that would come later. Both cartoonists used an eclectic cast of slice-of-Americana characters to discuss current events. And both were unusually political for the comic strips of the era, which mostly stuck to safe sitcom material. Early on, Trudeau’s periodic hiatuses from Doonesbury allowed Breathed to replace him in some newspapers.

But in retrospect, Bloom County came from a fundamentally different perspective. Trudeau emerged from the 1970s late-counterculture tradition of National Lampoon and Saturday Night Live: erudite young left-wingers, trained on Ivy League humor magazines, out to smash the system with subversive comedy as a vehicle for progressive politics. Breathed’s strip anticipated the next generation, the style that would replace Lampoon-ing: media-saturated, self-referential, political only to the degree that politics is part of pop culture, as surreal and anarchic as a two-in-the-morning flip up the TV dial. The humor of Bloom County is the humor of The Simpsons and all that came after.

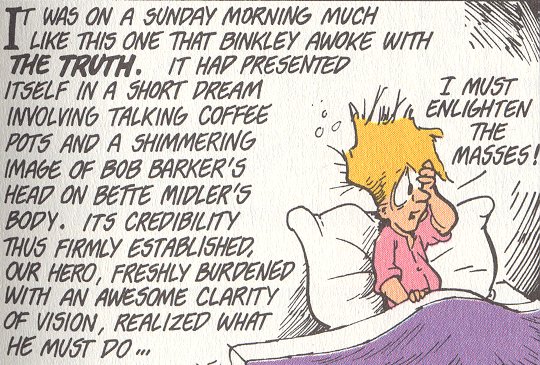

In its original context, the “Knight Rider” line is spoken by Binkley, the only Bloom County character to outpace Opus in gormless naïveté, after mysteriously awakening with a revelation of The Truth in all matters. The other knowledge Binkley shares: the Monkees didn’t play their own instruments, Opus looks more like a puffin than a penguin, and Reagan will never fulfill his promise to share Star Wars missile defense secrets with the USSR. That all of these revelations are presented as equal in importance sums up the difference between Bloom County and Doonesbury.

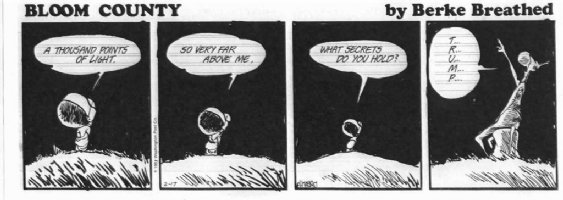

And that was life in America in the 1980s. The political became the personal, then it became the trivial. Colors were bright, patterns disorienting, everything expensive and hideous. The president was a movie star, of course, but more to the point it seemed reasonable for the president to be a movie star, to be just a guy hired to play The President. Billions of lives depended on a missile defense system named after the movie franchise that had just introduced Ewoks. We couldn’t handle the truth about the government or our souls, but neither could we handle the truth about David Hasselhoff. In Bloom County, Bill the Cat, the strip’s Garfield-parodying symbol of half-assed commercialism, has two recurring careers: rock star and presidential candidate. The careers are close to interchangeable and often inspire near-identical storylines. In the final years of the strip, Bill switches brains with Donald Trump, the human embodiment of the peculiar mishmash of money, politics, celebrity, and tackiness that could be said to define the decade.

Many of the most successful Bloom County strips make a social observation without making a social statement. When the characters go hunting for the endangered liberal by baiting a trap with the Village Voice (“Just let me read the Feiffer cartoon!”), it’s very funny, but it doesn’t express any particular viewpoint about liberals or conservatives or American political debate. (Which is not to say that the artist’s personal views don’t sometimes come through; Breathed seems consistently uncomfortable with women and feminism, for instance.) One of the most famous Bloom County storylines begins with boy genius Oliver responding to South African apartheid by inventing a “pigmentizer” that turns white people black. An earlier generation of political humorists would have built this into a moralistic civil-rights fantasy, or followed the premise to disturbing and challenging places. A story that starts with apartheid has the potential to get dark. Instead, the gang gets lost at sea on the way to South Africa, leading to Opus eventually returning to Bloom County with amnesia, which is ultimately cured by news of Diane Sawyer’s wedding. Race relations, soap opera parodies, celebrity gossip: they’re all potential comedy material. Bloom County’s central innovation was to reject the old-fashioned idea that they should be different kinds of comedy.

The Simpsons played the same tune, ten years later, when it responded to Bush Sr.’s criticisms of the show’s crassness with “Two Bad Neighbors,” an episode portraying George and Barbara Bush as George and Martha Wilson from the 1950s Dennis the Menace TV show. In the DVD commentary for the episode, writers Bill Oakley and Ken Keeler comment that the older writers on staff were frustrated by the episode; they wanted a show about the President to be a sharp-edged political satire, not a pop-cult parody where the basic joke is “George Bush is old.” But the younger writers didn’t want to do satire. And George Bush was old.

To some degree Bloom County, which ran from 1980 to 1989 precisely, is of its time. In sheer volume of cultural detritus invoked, it certainly stands in stark contrast to the other great 1980s comic strip, Calvin and Hobbes, which strove for a sense of children’s-book timelessness. (My friend Jason Thompson once commented that he always found himself waiting for Calvin to pick up a video game controller.) Yet Donald Trump is still with us, all these years later, and so is David Hasselhoff, and so is the Bloom County sense of humor, the comedy that comes from collapsing every cultural signifier to a single level of blind, bland confusion and romping through the ruins.

Only occasionally does Bloom County take a coherent political or social stand, most notably in its extended attack on animal testing. More often, it adopts a “both sides are just as bad” attitude, or simply seems baffled by all the fracas. When Breathed abandons his post-counterculture cynicism and reaches for a sweet and gentle note, he usually does so by having the characters abandon their pop-culture wasteland entirely for a trip to the swimming hole or the dandelion patch. In Bloom County, there’s no salvation in political action or cultural revolution; the only hope is to drop out of our oversaturated civilization and go looking for reality. And that, maybe, is the final truth.

_____

The entire Bloom County roundtable is here.

That’s a great piece! The point about not being able to figure out Breathed’s politics is a way more cogent way of saying something I tried to say, which is that in secular humanist realism, the center-left liberal politics are (as in “the liberal media”) projected dimly but consistently through a kaleidoscopic world of absurd squabbles as the least bad of all bad options.

YES. Thank you for writing this Shaenon. I felt perplexed reading Bloom County, because I kept expecting it to be political satire. I think your reading of the truth, that Bloom County treats politics are just another kind of pop culture, is excellent– and also the credit you give Breathed for pioneering this stance.

Also, thanks for the short mention of Breathed’s uneasiness with women and feminism. I tried to get a post together on that and fell short, but would love to hear you elaborate on it.

So I really like this post too, but maybe disagree with it at least in part.

First, in terms of the feminism…I guess I go back and forth on this? I don’t think Breathed is actually opposed to feminism; the anti-feminist voice in the strip is Steve Dallas, who is pretty clearly marked as an idiot and a bounder. I also think the female characters in the strip are at least attempting to be well rounded and interesting. I do like Bobbi Harlow, who sort of disappears over time, but who is obviously supposed to be a strong female character (fairly literally) and while I’d say you can see him straining, which is not ideal, I at least appreciate the effort.

I like Yaz Pistachio too (despite the problems with falling for Opus) and Steve’s mother is a stereotype, but kind of great for that. I like Tess Turbo too…I mean, I wouldn’t say he’s great or anything. It’s no Peanuts. But it seems like it could be worse.

I don’t in general feel like Breathed’s leftist politics are hard to pin down necessarily, either. He had a series about decriminalizing drugs, for example; he wears his animal rights activism on his sleeve, he tries hard for diversity (Oliver Wendell Jones is way more successful than Franklin in this regard.)

I do think as Kailyn says that he treats politics as pop culture. But I kind of think politics is pop culture — or at least, analyzing politics as pop culture is a political statement in itself, rather than a refusal of politics.

I think the Doonesbury influence is heavier than you let on. To me, the biggest similarity between the strips is their timing, which uses two people talking in the final panel to save the ultimate punchline for the last second. That seems to make everything funnier, and I think Trudeau started it. Also, the Bloom County characters escaping to nature may have been influenced by Doonesbury, in which Zonker had “Walden Puddle” and Mike used to lie around in a field with the ghetto kid he was tutoring. And the Bloom County sequence about hunting endangered liberals is a little like the Doonesbury thing about transplanting a liberal’s heart into a conservative’s brain. (“Are you sure the donor is a liberal?” “Well, we pulled him out of a Volvo.”) Maybe that last one is a stretch, though.

I’d say The Simpsons was pretty left-wing in the early years. Mr. Burns polluting, breaking strikes, and trying to buy the governorship; the angel episode that starts by making fun of religious fundamentalism but ends with the revelation about the new mall… It has some pretty heavy political themes early on.

I frequently find myself saying “Peer pimples for hairy fishnuts!”. No one ever seems to know wtf I’m talking about. I do my Bill The Cat face, and they don’t get that, either. Not even the jokes about being elected Vice President while out getting Doritos, or the USS Enterpoop, or AT&T as the Death Star.

Alas.

I’m always saying, “I’m appalled with two “p”s. People just look at me funny.

This was the best so far — no offense to the other fine entries. I agree with Noah that Breathed was more comfortably and genuinely feminist than Shaenon believes, and that his politics were clear. It didn’t matter, though. Breathed harvested absurdity wherever he found it, and like a good court jester, made fun of us all.

I find myself saying, “I’m moving just as lickety-dang-split as I can.” That comes up all. the. time. For reals.

Oh, and “Youd’n be a lawyer!”

One cavil — National Lampoon was actually pretty right-wing overall. Check out the back issues. It’s no coincidence, too, that today’s premier right-wing satirist is P.J.O’Rourke, whose comedy career started at the Lampoon.

Pingback: Kibbles ‘n’ Bits 2/25/2014: What this cartoonist has to tell you about time management will make you drool into a bib — The Beat

Pingback: Kibbles ‘n’ Bits 2/25/2014: What this cartoonist has to tell you about time management will make you drool into a bib | ComicBookRAW

Noah: “First, in terms of the feminism…I guess I go back and forth on this? I don’t think Breathed is actually opposed to feminism; the anti-feminist voice in the strip is Steve Dallas, who is pretty clearly marked as an idiot and a bounder. I also think the female characters in the strip are at least attempting to be well rounded and interesting. I do like Bobbi Harlow, who sort of disappears over time, but who is obviously supposed to be a strong female character (fairly literally) and while I’d say you can see him straining, which is not ideal, I at least appreciate the effort.”

I wonder if your generosity on this isn’t determined by extraneous factors, since you’ve found some quite arcane reasons to accuse other cartoonists of misogyny and Bloom County was full of jokes about hairy-legged man-hating feminists.

Bloom County was full of more jokes about how right wing anti-feminists are asses, though.

I don’t think my reasons for these things are usually especially arcane. I’m not claiming that Breathed is incredibly good on gender (like I said, he’s no Charles Schulz.)

Have to disagree with “Trudeau emerged from the 1970s late-counterculture tradition of National Lampoon and Saturday Night Live”; Doonesbury debuted in the Yale Daily News (as “Bull Tales”) in 1968, and was syndicated in 1970. SNL didn’t debut until 1974, and National Lampoon also started in 1970. If anything, Doonesbury was an influence on SNL and the various Not Ready For Prime Time Players. But it’s pretty much impossible for either SNL or the Lampoon to have been a tradition for Doonesbury to have emerged from.

Noah, I think your articles on Ghost World that find hidden clues in panel compositions that Clowes is systematically dehumanizing Enid can reasonably be described as arcane, and most readers would have difficulty discerning why Breathed (or Alan Moore, for that matter) ain’t perfect with the ladies but deserves credit for trying while Clowes is a misogynist, sadistic bully. If your treatment of them is an anomaly maybe you could point me to some more solid analyses you’ve written of a cartoonist’s problems with gender.

Deelish, I wait for the day that you leave a comment to me that does not reference the fact that you disagree with me about Clowes. Not holding my breath, though.

This must be what they call “manspalining,” right?

I don’t think so…? I’m explaining why I think the strip maybe does better with these issues than Shaenon seems to think it does. I don’t even know if she’d disagree; her comment was pretty offhand. It’s pretty clearly phrased in terms of my own take, I’m not saying there’s nothing there.

I guess there’s an argument to be made that men shouldn’t talk about these issues at all and/or should never contradict women. That ends up being kind of condescending I think though. I don’t think turning any respectful disagreement or discussion into mansplaining is particularly helpful to anybody.

I mean, I was hoping Shaenon would elaborate on what she took to be the problem, but she doesn’t seem to be following the thread, unfortunately.

Dude….

First of all, I have enjoyed Bloom County and later Outland for many years. Recently I was cleaning my attic and found a copy of ‘Loose Tails’ in a box. Remembering how fond I was of reading the strip, I started reading the book. After page 84, I noticed the page numbers and comics starting again at page 69, then again and again. Three times the book repeated the same pages and comics. Is this a misprint or was it intentional?

That’s a misprint.