In the comics memoir, Sentences: The Life of M.F. Grimm, Percy Carey tells of his experiences growing up in New York, finding success as an emcee in the early 90s, and getting caught up in the drug trade and gang shootings that would eventually leave him paralyzed from the waist down. Artist Ron Wimberly sketches Carey on the graphic novel’s cover in a wheelchair as he is now, rather than surrounded by fans or performing on the stage he once shared with names like Snoop Dogg and Tupac. The choice is fitting, given Carey’s interest in conveying the social and economic realities of his life behind these scenes and after spending time in prison.

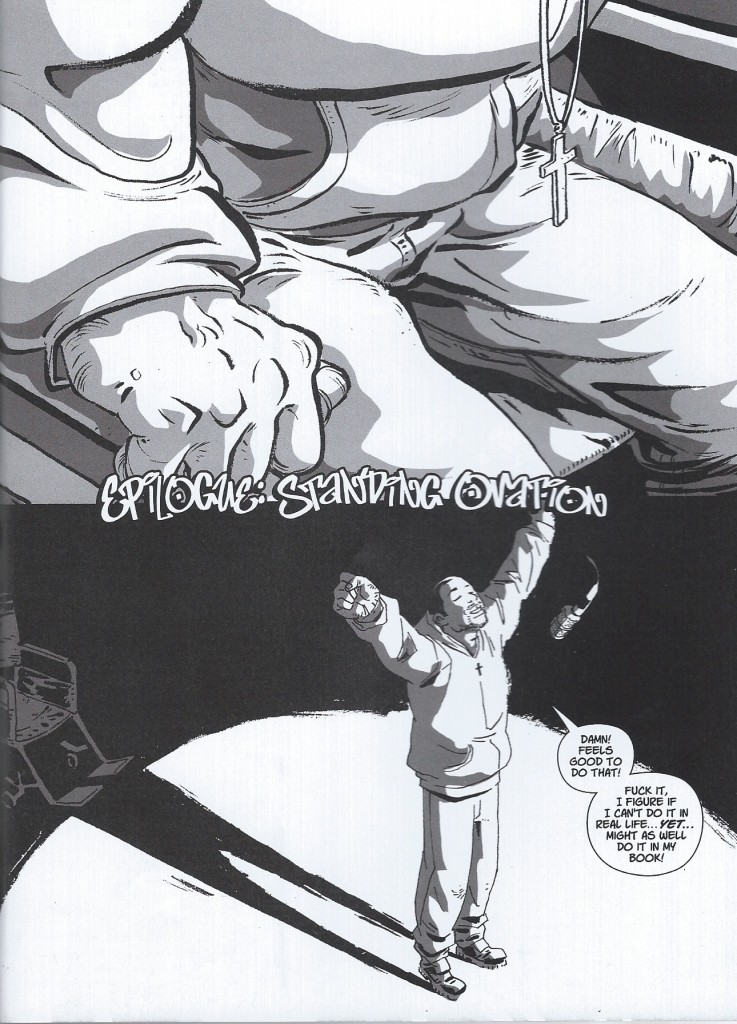

But in the epilogue subtitled “Standing Ovation,” Carey grasps the wheelchair’s arms and pushes himself up. A microphone dangles in the air above him. With his arms stretched out, chin raised, he steps forward and says: “Damn! Feels good to do that! Fuck it, I figure if I can’t do it in real life…yet…might as well do it in my book!”

When we are asked to consider what makes comics unique, I think that our conversation should include scenes like this one. We know that the distinguishing features of comics can extend beyond formal elements to include stylistic practices that develop and advance whenever a sequence of words and pictures tell a story. In this case, Sentences provides an opportunity to talk about what happens when genre conventions refuse to stay put in graphic narratives that are based on actual events.

I’m curious about what Carey’s story accomplishes here by stepping away from what he can’t do “in real life.” Reviews of the comic are unequivocal when it comes to praising his honesty, his unwillingness to glamorize hip hop culture or the drug trade. What, if anything, changes when Carey (in collaboration with Wimberly) frees himself from the wheelchair and in the process, releases his story from the constrictions of nonfiction? By bracketing off the moment in an epilogue, the comic arguably reaches the only kind of happy ending possible without threatening the story’s credibility. At the same time, the utter joy and pleasure that he takes in the visual representation of his body makes the fact that we are dealing with a comic particularly important. Is it enough to say that Carey wishes for the ability to stand or that he imagines what it might be like to walk again when on the concluding pages of his book, he actually does?

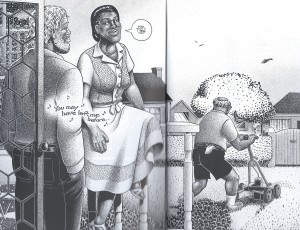

Howard Cruse’s Stuck Rubber Baby provides a second example. The semi-autobiographical narrative is anchored to the Civil Rights demonstrations of the 1960s, but the comic also breaks away from the “real” in its closing pages. The protagonist, Toland Polk, opens a patio door in the snowy, urban setting of his present and with the sounds of a jazz record curling around the panel, he ushers the viewer into a summer day from his bittersweet Alabama past. As with Percy Carey’s comic book persona, Toland steps out of the story to prepare the reader for this moment. (“There’s something I wanna show you!” he says prior to this page.) The image fills our entire field of vision, maintaining the style and aesthetic features of the rest of the comic in a way that doesn’t merely depict what Toland imagines, but communicates deeper sensations that the viewer experiences within the primary narrative frame.

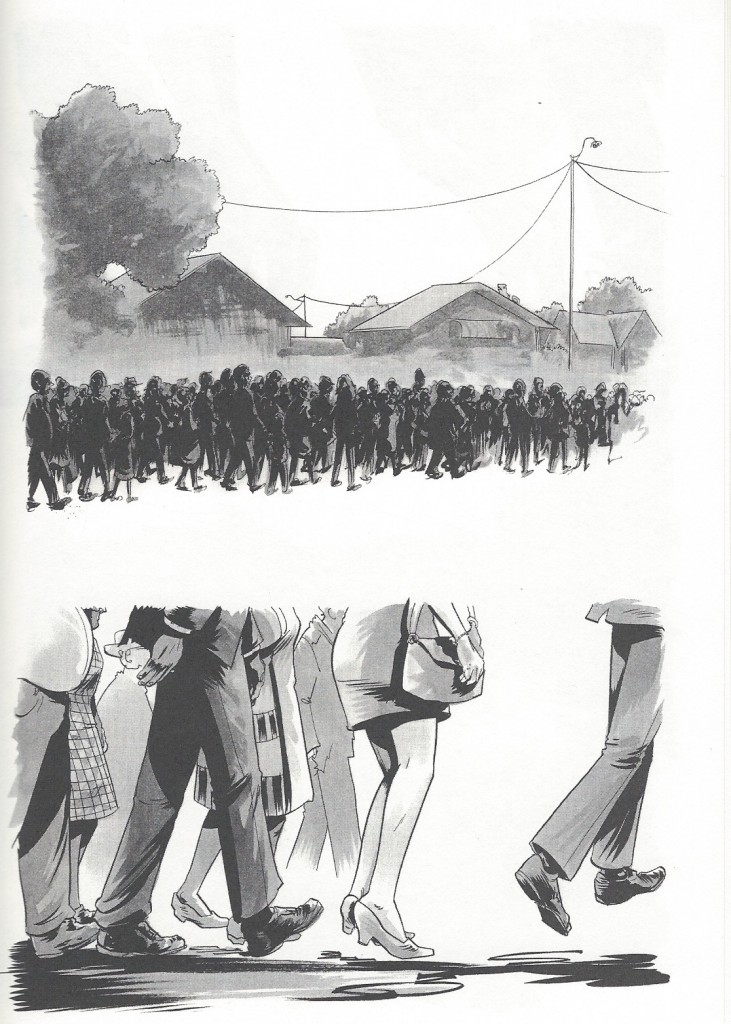

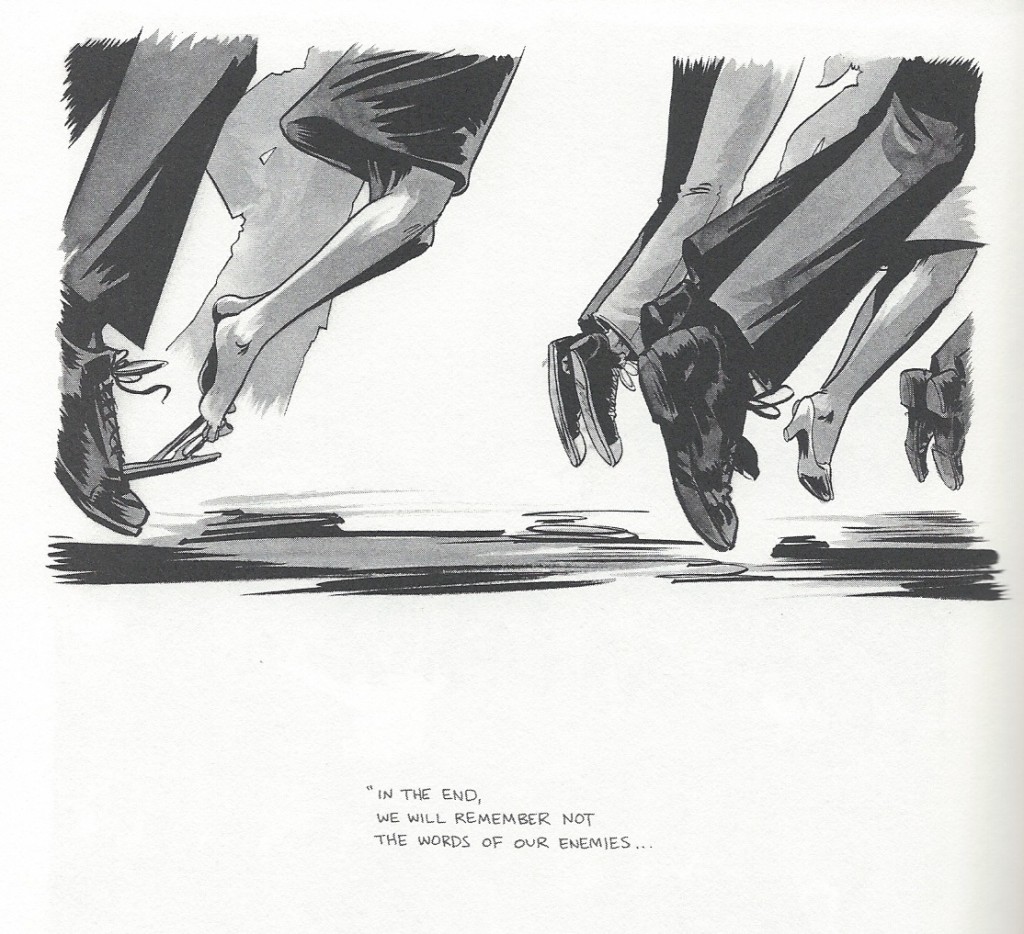

In both examples, dialogue is deployed strategically and in a metafictional way to shape our encounter with realistically-pictured conjecture. But what happens when there are no words to guide us? In my last example from The Silence of Our Friends by Mark Long, Jim Demonakos, and Nate Powell, a Civil Rights demonstration ends the graphic novel which focuses on the story of a black and white family involved in the events surrounding a police shooting at Texas Southern University in 1968. The comic is based on the experiences of Long and his father who worked as a television reporter in Houston during this time.

Powell closes the story with a procession of silent marching figures to accompany the Martin Luther King, Jr. quote that serves as the book’s title. The shoes shuffle slowly from panel to panel until they lift without warning and begin to float up. Their flight could be said to signify the protestors’ courage or suggest a longing for social and spiritual transcendence in honor of King’s assassination that year. It could even allude to elements of African myth. Whatever it accomplishes, it does so with no clear verbal signposts, shifting seamlessly into the speculative realm through illustration.

Where do these strange endings leave us? How does this resistance to more realistic representation alter the way we encounter the real in nonfiction comics? Could it indicate an unwillingness to truly face hard, unresolved suffering and social conflict? Or are we so accustomed to comic book flights of fancy that using the tropes more commonly associated with superheroes just feels damn good, to paraphrase Percy Carey, in any type of comic?

A great post and starting point, but I’m unconvinced this is comics-specific, and not just a narrative choice. The Grease movie ends with a similar ‘lift off,’ where the heroes get in the car, and drive off from the school fair into plain air. I’m not a huge Grease fan, but this choice always intrigued me, and I thought was a graceful way to say “By the way this whole film was a fictional exercise in nostalgia and all these characters no longer exist/never existed. Hope you enjoyed it!” The lift-off trope, and maybe Carey’s lift-up, is a heavenly fantasy. Lift-off suggests the Rapture, and lift-up Christ’s miracles.

I think that this is Christian imagery is also very fitting, considering these comics concern the struggle for Civil Rights.

I’m curious about the assumption that moving into clearly fictionalized (and in this case, fantastical) gestures necessary indicates escapism. Or at least, that’s how i read: “How does this resistance to more realistic representation alter the way we encounter the real in nonfiction comics? Could it indicate an unwillingness to truly face hard, unresolved suffering and social conflict? Or are we so accustomed to comic book flights of fancy that using the tropes more commonly associated with superheroes just feels damn good, to paraphrase Percy Carey, in any type of comic?”

This is a bit difficult to discuss, having not read the comics you discuss (although I;ve read a lot of Nate Powell, Silence is next on my list), but I can imagine that having an ending in which the protagonist imagines stepping out of his wheelchair and then says to the reader that this section is a fantasy would be more, rather than less, heartbreaking. Or at least tonally complex. The narrator is acknowledging that the “happy ending” is a forced fantasy, right? Doesn’t this heighten our awareness of the real, rather than escaping from it?

“I can imagine that having an ending in which the protagonist imagines stepping out of his wheelchair and then says to the reader that this section is a fantasy would be more, rather than less, heartbreaking.”

That’s basically how Iam McEwan’s Atonement works. (Though that’s fictional, so the fact that the fictional happy ending is presented as “not real” is itself complicated, since the “real” tragic ending isn’t real either.)

I think Isaac has a point here. These gestures seem more like triumphs of the power of fiction and storytelling. I also stick with the idea that the imagery in all three examples is much more Christian Apocalyptic than it is super heroic.

I think the book (and film) Atonement does a good job of discussing where this triumph is escapist, and when it serves as a truer testament to human spirits. Tim Burton’s Big Fish as well, but less deeply. (Never read the original book.)

Very interesting article. I greatly enjoyed it. Like Kailyn, I was also prompted to consider how similar techniques can be found in movie. That being said, I don’t think citing isolated examples from other media necessarily disqualifies the possibility that this could be viewed as a distinguishing feature of comics.

To add a somewhat inverse example, your article made me think of the final scene of the animated documentary “Waltz with Bashir,” which moves in the opposite direction, from a stylized animation to real archival footage from the Sabra and Shatlia massacre. It’s a brilliant transition that effectively strikes the viewer not just with the reality of the movie’s events, but the sheer weight of the victims’ suffering. In this sense, it shows how the technique you identify can be reversed to deny the viewer any resistance to a harsh reality the first 90-minutes of animation approached more delicately.

I think it’s true that you can have this sort of move in other kinds of mediums. But I think Qiana’s right too that seeing this in a comic tends to call to mind supeheroes in a way it might not in other venues. It’s hard to make folks fly in an American comic and not think at least a little bit about Superman.

I was concerned that these three examples would come across as too selective so I appreciate you all helping me think through this question. Keith, thanks for the reference to Waltz with Bashir – that’s a really good inverse example.

Isaac, your point about escapism and tonal complexity is helpful. I was hoping to convey something similar by noting that while the words call attention to the fantasy, the images push back and make an opposite reading possible. There aren’t any thought bubbles, for instance, or stylistic variations to say “this is not really happening” (although I realize these features are falling out of favor more generally). There’s a risk to doing this, I think, when we’re talking about comics in which the claim of “based on actual events” is highly valued – both within the stories as well as in the promo materials, the interviews, and reviews. I definitely think it can heighten our awareness of the real…Silence more so than the others.

It may be going to far too argue that these gestures are comics-specific as Noah and others have said, but I still feel that memoirs, semi-autobiographical comics seem to take advantage of the form in a way that you don’t often find with a prose memoir or film biopic.

Kailyn, I find the reading of the Christian symbolism actually really persuasive when it comes to Silence though not as much with Sentences. Religious imagery has its own complicated relationship to realism, which might explain why Powell et all were more willing to include in this kind of story (especially alongside the reference to MLK) without additional comment.

I really like the style of the recent PPP posts, including this one, which — instead of trying to nail down an argument — chooses to open up a conversation, with suggestive patterns and thoughtful questions.

I have little to add, unfortunately. But I am guessing that the creators of “Silence” may have, like me, had Leo and Diane Dillon’s imagery in their heads. This book was everywhere in the late 80s and 90s, at least in schools and school libraries.

It just occurs to me that someone it might be interesting to look at in this regard is Gabrielle Bell? She often presents her comics as autobiography, or within indie autobio convention, and then takes a turn into surrealism or fantasy. It’s not exactly what you’re describing here, but seems somewhat related…and predicated on the ease with which comics can cross the line between reality and fantasy (as well as on comics convention or expectations, since she makes use of autobio expectations.)

Then again, part of your question seems to be, “Can comics — because of some formal or associational difference — “get away with” this kind of border-blurring move (or perhaps this kind of sappiness) more than other forms of storytelling?” That is to say, each of these endings is almost absurdly saccharine, right? But do we give comics more leeway — do comic artists give themselves more leeway — than creators in art forms that are more explicitly coded as “real.”

To do this in film, you’d have to embrace the fantasy, like in the ending to De Sica’s “Miracle in Milan,” or you’d end up with something more like the “Bob Lamonta Story.” Or at least a Jack Chick comic.

P.S.: Another probable “Silence” source.

Noah, what Bell texts do this? I have a few of her diary comics, but don’t recall much blurring.

Adding Gabrielle Bell to my list…

Peter, exactly yes, I was positing that comics are “getting away with” the border-blurring in a way that other forms do not. Or at least, the use of the form has evolved so that this is becoming more common practice. Thanks also for your kind words – you should write a guest post for PPP!

A few critics have said things about the “effect” of the comics form on melodramatic (or sometimes mediocre) material that might apply here. Two come to mind, both from 2004 and about Craig Thompson’s “Blankets.”

Charles McGrath, in the Times, said “How good are graphic novels, really? … Hard to say. … The graphic novel can make the familiar look new. The autobiographical hero of Craig Thompson’s ”Blankets,” a guilt-ridden teenager falling in love for the first time, would be insufferably predictable in a prose narrative; here, he has an innocent sweetness.”

Jules Feiffer, talking to Chris Ware, said sometime similar in the Comics Journal: “If he [Thompson] were writing this as a novel…it might be rather banal: just one more story about one more kid misunderstood…, trying, guilt-ridden, to discover his own identity.” It’s the form, Feiffer implies, that saves the book, and “traps” him as a reader (in a good way).

Ware, in his silence, clearly doesn’t share Feiffer’s enthusiasm.

Another artist who often blurs these lines between autobiography and fantasy is Corrine Mucha. I’ve probably raved about her comics to you before, Qiana! The Girl Who Was Mostly Attracted to Ghosts is a great place to start:

http://maidenhousefly.com/SHOP-COMICS

She has a new book coming out from Secret Acres this spring, too.

I wonder if these moments of the fantastic or daydreaming in these otherwise realistic comics might place these stories in the same tragicomic tradition as Don Quixote, or Thurber’s Walter Mitty, or (more tragic than comic!) Arthur Miller’s Willy Loman. I suspect the blurring of these distinctions might also be the continued presence of comics’ pulp origins. I’m thinking of the psychoanalytic realism of a story like Fritz Leiber’s “Smoke Ghost” and its gradual descent into the utterly fantastic. And Harlan Ellison likes to blend the two forms in his best work–“Jeffty Is Five” and “One Life, Furnished in Early Poverty,” for example. And, as he often likes to say, he learned to write from reading the Golden Age comics of his 1930s and 1940s childhood!

Pingback: Kibbles ‘n’ Bits 3/17/14: Top o’ the Kibble to ye!