That’s what Alan Moore told a recent interviewer. “I don’t think the superhero stands for anything good,” he said. “They were originally in the hands of writers who would actively expand the imagination of their nine-to-13-year-old audience.” But since all they do nowadays is entertain 30-60-year-old “emotionally subnormal” men, Moore considers superheroes “abominations” and their continuing dominance “culturally catastrophic.”

This from a self-professed anarchist who considers the shooting of government leaders a “lovely thought.” Little wonder his first superhero was a terrorist.

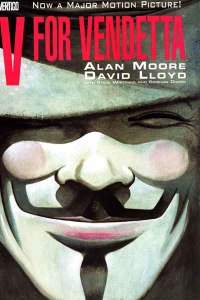

Moore and artist David Lloyd started V for Vendetta in 1981 for England’s since defunct Warrior magazine. I started reading it when the series moved to DC in 1988. I was 22, Moore’s age when he first conceived a story about “a freakish terrorist” who “waged war upon a Totalitarian State.” But it was Lloyd who transformed Moore’s freak into “a resurrected Guy Fawkes, complete with one of those paper mâché masks in a cape and conical hat.”

Their plan was to create “something uniquely British,” and, sure enough, the Fawkes reference meant absolutely nothing to this Pittsburgh-born college senior. When I’d read The Handmaid’s Tale the year before, I though Margaret Atwood was forecasting an original future: “when they shot the president and machine-gunned the Congress . . . The entire government, gone like that.” But Fawkes beat her by almost four centuries.

I didn’t read up on the Gunpowder Plot till I was a student teacher prepping Macbeth for a class of tenth graders. Shakespeare staged his tragedy of a regicidal anti-hero after Catholic terrorists tried to blow-up King James during the 1605 opening of Parliament. They’d rented a storage space under the House of Lords and crammed in three dozen barrels of gunpowder. Fawkes was arrested before he could light the fuse, tortured into betraying his dozen co-conspirators, tried, hanged, and his body displayed in pieces as a warning to sympathizers. He was still in prison when London lit bonfires in celebration of the King’s survival, and Parliament later declared the anniversary an official holiday, complete with fireworks and newspaper-stuffed “guys” set ablaze.

But hatred is a funny thing. Somewhere along the line the point of all those celebrations got hazy. Guy Fawkes Night lost its official standing in the 19th century—around when penny dreadful writers were converting England’s most abominable traitor into a romantic hero, a conspiracy Lloyd happily joined. “We shouldn’t burn the chap every Nov. 5,” he told Moore, “but celebrate his attempt to blow up Parliament!”

I want to say the American equivalent would be championing John Wilkes Booth or Lee Harvey Oswald, but Fawkes’ rehabilitation might be possible only because his assassinations failed. Benedict Arnold could be closer—except no one remembers what treason he was planning (and even if you do, surrendering West Point to the British just doesn’t have the same audacious charm).

So Lloyd wanted to “give Guy Fawkes the image he’s deserved”—but I’m not sure Moore was fully committed to the plot. Despite his anarchist rhetoric, he doesn’t “believe that a violent revolution is ever going to work,” and he doesn’t hide his freakish terrorist’s violence under POW! and BAM! bubbles either. It was Lloyd who banned the sound effects (along with thought balloons—probably the most important moment in Moore’s development as a writer), but Moore’s dialogue complicates the violence Lloyd renders otherwise bloodless:

“I’ve seen worse, Dominic, physically speaking. Like I say, it’s the mental side that bothers me . . . his attitude to killing. Think about it. He killed them ruthlessly, efficiently, and with a minimum of fuss. Whatever their faults, those were two human beings . . . and he slaughtered them like cattle!”

The terrorist also enters quoting Macbeth, the monstrous anti-hero Shakespeare’s audiences (including King James for whom it was commissioned) would have linked to Fawkes. Moore’s Chapter One title, “The Villain,” is a bit of a clue too. V goes on to murder and maim his way through some thirty more chapters, but the part that troubled me most at the time was the psychological torture he inflicts on Evey. Yes, he rescues the damsel from a back alley rape in standard Batman fashion, but then he dupes her into believing she’s been imprisoned by the fascist government, shaves her head, starves and waterboards her, all in the name of . . . what exactly? By the end Evey is a good little Robin, taking on her mentor’s mission, but there’s more than a whiff of Stockholm syndrome between the panels.

“The central question is,” Moore says, “is this guy right? Or is he mad? I didn’t want to tell people what to think, I just wanted to tell people to think and consider some of these admittedly extreme little elements.”

Which, by the way, is a pretty good example of using a superhero to actively expand an audience’s imagination.

Meanwhile, Guy Fawkes keeps adventuring. The “hacktivist” network Anonymous adopted Lloyd’s Fawkes mask for their 2008 Scientology protest—which they then carried over to Occupy Wall Street and, most recently, a worldwide Million Mask March held on Guy Fawkes Day to protest government austerity programs. The group’s anti-corporate message, however, gets a bit hazy once you know Time Warner owns the copyright on the mask (via DC I assume) which are manufactured in South American sweatshops and earn the company a killing on Amazon.

Something to think about, Moore might say.

Another typically perceptive and entertaining post by Chris!

A little etymological aside: the Guy Fawkes figures burnt in effigy led to the English use of “guy” to designate a figure of fun, someone ridiculous: “I looked a proper guy standing there with my trousers down.”

When the word crossed the Atlantic, ‘guy’ came to be generalised to mean ‘fellow’, ‘chap’; at first men only, as in ‘Guys and Dolls’– but nowadays I hear ‘guy’, especially in the plural, refer to women as well.

In recent decades this American use has crossed back into Britain and is adopted there now.

Another influence on ‘guy’ may have been ‘guiser’, an old word for trickster or jester; it survives in the slang word ‘geezer’;

(In the USA ‘geezer’ only designates old people, but in Brtain it just means a male person, a chap or bloke, with no idea of age.)

I don’t think Moore would consider V a superhero. I say this because he doesn’t seem to consider the League of the Extraordinary Gentlemen characters to be superheroes.

Fantastic work as always, Sir.

I think Moore’s work, generally speaking, works because of the ambivalence at the heart of it.

“but then he dupes her [Evey] into believing she’s been imprisoned by the fascist government, shaves her head, starves and waterboards her, all in the name of . . . what exactly?”

I believe that’s an example of Wagner’s “But one weapon serves: only the Spear that smote you can heal your wound.”

I really liked the article. Would you mind if I translated it to a Brazilian blog?

It is very interesting that in Brazil, where people mostly haven’t read Moore’s ambiguous anti-hero, just watched Warner’s movie about the libertarian savior, the mask is used in protests against corruption. Some self-called Anonymous groups are violently against left-wing parties and have promoted violence against leftist activists during the 2013 protests. They are, sometimes, well-intended fascists, inspired by a Hollywoodian superhero, a theme this blog is constantly talking about.

V has a cape, and a mask, and a secret identity, an underground headquarters with a cool name and superpowers. V got his superpowers through pretty much the same method as Captain America did. As Chris Gavaler mentioned, he mentors a young sidekick, who ultimately dons a mask and cape.

Whether or not Moore considers V to be a super-hero (or super-villain), Moore certainly gave V all the trappings of one.

Thank you, Alex and Osvaldo, for the kind words, and, Vin, yes, by all means please translate all of my posts for any Brazilian blogs you like. And then send me a link so I can stare uncomprehendingly but happily at the results.

Moore definitely has a love-hate thing with superheroes that belies some of his statements in interviews. Has anyone else read Gary Groth’s massive Big Numbers-era interview with Moore, which was spread out over three issues of TCJ? When Gary brings up Harvey Pekar’s position that not only superheroes but all genre literature is second-rate, Moore pretty much agrees with that view. He also compares Image Comics to crack cocaine and says he’s glad to be separating himself from that kind of thing. But in the years since the interview, he’s done tons of genre and superhero work, some of it for Image! I’m not really complaining; I just think he’s torn between highbrow aspirations and lowbrow interests, which is part of the overall strangeness that makes him a good or great artist.

I read that interview and comment on it in the intro to my Moore book (Alan Moore: Conversations). He totally backtracks out of the anti-genre argument in other interviews (including the 2009 Mustard interview included in the book). He includes superheroes in his new League books too…not just proto-superheroes, but actual superhero superheroes. He’s not against them. He’s just against DC and Marvel’s business practices (and he’s not impressed by the latest superhero work either—but then again he also admits to not having read or seen any of it).

That Groth interview is one of the 2 or 3 best Moore interviews available. He wouldn’t let me use it.

Thanks, Eric. I hope to read your book eventually. When the Groth interview first came out, I was really excited by it. “This guy is a fucking genius who’s going to take his comics to a whole new level, to the point where Watchmen looks like embarrassing juvenilia!” He did go on to do From Hell, which might be his best work, but it’s a shame that Big Numbers fizzled and he seemed lost for a while.

Anyway, he does seem to take a blanket anti-superheroes position in “The Last Alan Moore Interview,” doesn’t he?

I’m not aware of any significant use of superheroes in League, just some cameo references maybe?

In 2010 he said they were American imperialist fantasies:

“I’ve had some distancing thoughts about them recently. I’ve come to the conclusion that what superheroes might be – in their current incarnation, at least – is a symbol of American reluctance to involve themselves in any kind of conflict without massive tactical superiority,” Moore said. “I think this is the same whether you have the advantage of carpet bombing from altitude or if you come from the planet Krypton as a baby and have increased powers in Earth’s lower gravity.”

The graphic novelist said that, when he was a child, superheroes represented “a wellspring of the imagination”. “Superman had a dog in a cape! He had a city in a bottle! It was wonderful stuff for a seven-year-old boy to think about,” Moore explained. “But I suspect that a lot of superheroes now are basically about the unfair fight. You know: people wouldn’t bully me if I could turn into the Hulk.”

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2010/jul/13/watchmen-alan-moore

Good article. I am from EU. Personally, I don’t hate superheroes. I simply find them boring. At the same time, I can’t understand the hyperproduction of these comics in America. America had so many wonderful comics. Why did the superheroes prevail? I do see a freudian background behind the phenomenon, while reviewing the covers with idealized or overly muscular human bodies in skin tight suits. The flying bodybuilders in a constant fight. I understand Alan Moore and his aims, though.

Eric — “He wouldn’t let me use it” Is the “he” Moore or Groth?

Groth, I’m pretty sure.

Well, for a while, Fantagraphics was putting out those “Comics Journal Library” collections of TCJ interviews, with volumes devoted to Miller, Crumb, and Kirby. I can see Gary wanting to hang onto his interview in case they ever go for a Moore volume that competes with Eric’s book.