In 1986, Frank Miller made headlines with The Dark Knight Returns, introducing a tougher, meaner, more Eastwood-like Batman, and kicking off the “grim and gritty” trend in adventure comics. The Dark Knight Returns is not only a good superhero story; it is also a comment on and critique of superhero stories, showing us the underlying mechanics and the foundational assumptions of the genre.

Another title, released that same year, did something similar. I don’t mean Watchmen (though it obviously did); I mean the largely overlooked Daredevil: Love and War. Also written by Frank Miller, and graciously illustrated by Bill Sienkiewicz, the novel offers an articulate critique of the kind of heroism implied by the ideals of chivalry. Years later, this critique became a recurring motif in Miller’s over-the-top noir series, Sin City. In both cases, Miller deploys sexist conventions in order to undermine them.

The Stories Men Tell Themselves

Love and War is explicitly about men, women, and power.

The book’s premise is that Vanessa Fisk, wife of Kingpin Wilson Fisk, has suffered some sort of psychological break and ceased to speak. Desperate, the Kingpin kidnaps Cheryl Mondat, the wife of a prominent psychologist. He then forces Dr. Mondat to treat Vanessa: “I could not simply hire you,” the Kingpin explains. “I want your passion, doctor. . . . You must know that you hold in your hands the life of the woman you cherish.”

Matt Murdock, the Daredevil, rescues the kidnapped woman — if “rescue” is the right word. “I make all the right promises,” he narrates; “She doesn’t cry. . . . Her voice is strong when she asks me who I am.”

“I’m a friend, Mrs. Mondat,” he says.

“And I’m your prisoner,” she replies.

Daredevil then sets off to attack Fisk Tower in a foolhardy effort to rescue the doctor. While he is away, Victor — the animalistic, pill-addled, psycho hired to kidnap Cheryl in the first place — manages by a combination of good luck and pure evil craziness to track her to Matt Murdock’s apartment, where he tries, not only to kidnap her again, but also to sexually assault her, and (given his previous performance) likely murder her in the bargain.

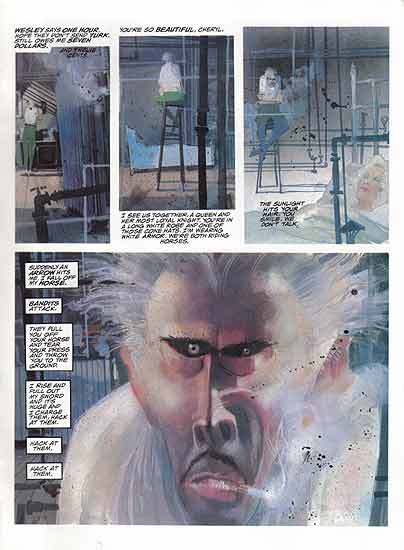

Surprisingly much of the story is given over to Victor’s point of view, and the narration — fragmentary though it is — recounts a delusional fantasy in which Victor is a knight and Cheryl a damsel in distress:

“I see us together, a queen and her most loyal knight. . . . Bandits attack. They pull you off your horse and tear your dress and throw you to the ground. . . . The bandits escape with my queen. . . . But I will find them. Save her honor.”

Elsewhere, he compares Cheryl to “Sleeping Beauty” and “Helen of Troy.”

The story Victor tells to himself is an inversion of reality: He is not her kidnapper, but her rescuer; not her attacker, but her protector. His intentions are not corrupt, but pure; his character noble rather than base; his actions chivalrous rather than criminal.

What stands out, as a result, is the way this hero story justifies Victor’s actions to himself, and how similar his justifications are to those of Daredevil. “She’s safe with me,” Matt thinks as he carries the drugged-unconscious woman to his apartment — though, like Victor, he has to remind himself repeatedly that “She’s a married woman.”

One could be forgiven for wondering if Murdock’s heroics, rather than providing the solution, might be part of the problem.

Failed Quests

It is not the Daredevil who saves Cheryl from Victor. She does that herself, cracking him across the face with a hot fireplace poker and then running him through. The image accompanying the coup de grace is, strikingly, that of a knight and queen riding into the sunset.

At the same moment Murdock, dressed as Daredevil, is assailing Fisk’s office tower. It’s a wasted effort. The task is impossible, and Matt is exhausted and injured before he even finds the hostages. By the time he reaches them, Vanessa, like Cheryl, has already found her own way to freedom.

With some gentle coaching from Dr. Mondat, Vanessa has managed to spell out a word using a child’s blocks. The word she spells is “XKAYP” — escape.

Her husband watches as the letters come together. “She stabs me,” Fisk thinks to himself. “She shatters me.”

It’s hard to know what we expect to happen next, but it’s pretty surely not going to be good. As Kingpin, Fisk has “built an empire on human sin,” and he maintains it through fear and cold, calculating violence. As Dr. Mondat was working with Vanessa, Wilson Fisk — “on a hunch” — ordered an arsonist “beaten with a lead pipe,” and then casually has one of his lieutenants, whom he suspects of treachery, assassinated. The scene is background, not even a subplot, just a moment of the day — but it reminds us who the Kingpin is, what he is capable of. How will such a man respond to his wife’s abandonment? What will he do to the doctor? to Vanessa?

The answer shows Fisk at his most human. He rages. He grieves. And then he relents. He flies Vanessa to Europe, gives her a fortune and a new identity. “The Kingpin will never see his wife again.”

As Fisk makes clear — not by saying so, but through his actions — his wife was never really his prisoner. Vanessa’s escape comes simply because she articulated her desire for it. Against all the conventions of the genre, in this telling it is the villain who behaves most decently.

By upending our expectations — about gender, about morality, and together, about heroism — Love and War also exposes them, and so exposes them to scrutiny. It turns out that a lot of what this story is about is, in fact, uncovering what these kinds of stories are about.

From Hell’s Kitchen to Sin City

On the surface, Sin City represents a vicious, vulgar blend of gendered stereotypes, sadistic ultraviolence, and paranoid conspiracy. For Frank Miller, however, “Every Sin City story is a romance of some sort.” As he told Publisher’s Weekly, “[E]ach story has a hero. There might be flaws. They might be disturbed, but if you look at it, ultimately their motives are pure. . . . they’re what I’d like to call ‘knights in dirty armor.'” The Sin City stories valorize these “knights,” but also complicate and undercut the chivalric ideal. Miller admits, of his knights’ quests, “They’re very dark, and the consequences are bad and they’re usually futile. . . .”

Men in the world of Sin City are all broad shoulders, hard fists, and gruff voices. The women are, with few exceptions, prostitutes or strippers; even those who aren’t rarely appear wearing more than lingerie. But, like Love and War, the Sin City stories push against the genre’s sexist assumptions.

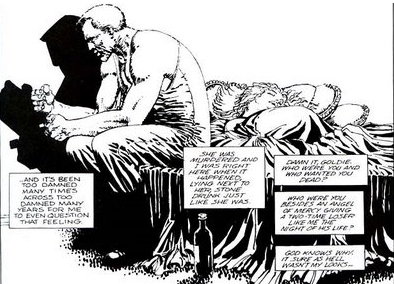

Nearly every novel in the series features a tough guy trying to protect, defend, or avenge a woman, and making a mess of it: Dwight McCarthy’s efforts to defend his girlfriend from her abusive ex set the stage for the mob to take control of prostitution in Old Town. John Hartigan, a rare honest cop, manages to save an eleven-year-old girl from a murderous pedophile, only to lead the killer straight to her again later. Marv — whom Miller has described as “Conan in a trench coat” — can’t protect his “angel,” the prostitute Goldie. He blacks out drunk, and when he wakes up she is dead. What’s more, these failures are described in mock-heroic terms. The dominatrix Gail teasingly calls Dwight “Lancelot.” Hartigan chastises himself for “charging in like Galahad.” Marv reflects, in his fashion:

“You were scared, weren’t you, Goldie? Somebody wanted you dead and you knew it. So you hit the saloons, the bad places, looking for the biggest, meanest lug around and finding me. Looking for protection and paying for it with your body and more — with love, with wild fire, making me feel like a king, like a damn white knight. Like a hero. What a laugh.”

I won’t try to find a “moral” to the Sin City stories, but if there’s a lesson to be learned, it may be that male heroics are not what keep women safe. What does? Apparently, their own collective activity. Dwight considers the relative security of Old Town, outside the control of the cops, the mob, or the pimps: “The ladies are the law here, beautiful and merciless. . . . If you cross them, you’re a corpse.”

Miller’s protagonists may be big men with trench coats and weather-beaten faces. But ultimately, it is the girls of Old Town who take care of the girls of Old Town.

Miller vs. Miller

Frank Miller — who likes drawing tits and ass almost as much as he likes drawing swastikas — does not enjoy a reputation as a feminist. And it is hard to know how well the politics of Love and War or Sin City honesty reflect his values or beliefs.

That uncertainty is largely a feature of Miller’s erratic and likely incoherent array of opinion over the course of time: He somehow went from writing about a Batman who “thinks he’s a damned Robin Hood” in Year One and organizes a revolution in the Dark Knight Strikes Again to railing against the Occupy movement as “nothing but a pack of louts, thieves, and rapists, an unruly mob, fed by Woodstock-era nostalgia and putrid false righteousness.” His immediate reaction to the September 11 attacks was explicitly anti-religious and anti-nationalist: “I’m sick of flags. I’m sick of God.” Yet a decade later, his Hitchens-like enthusiasm for war produced the execrable propaganda of Holy Terror. The Martha Washington series begins with a black girl literally imprisoned by poverty, but becomes an Ayn Rand-inspired fable celebrating the triumph of individual will.

Still, I think that the radical elements of his work, however muted, are more intriguing, more powerful, and more important than the reactionary aspects. Once one grasps that our entire culture is sexist, the fact that some comic book is also sexist may not seem all that interesting; but for the same reason, if that comic also resists sexist conventions, the fact that it does may be remarkable. Whether the author intended it to do so or endorses that reading likely says something about him, but doesn’t necessarily tell us very much about the work in question. It is, I think, worth considering — worth appreciating — those moments where some radical implication, deliberate or not, emerges from the text. In a way, it is almost better if the radical subtext is not intentional, if the subversive moment occurs simply because the story needs it — or further, because the stories that shape our culture cannot help but to suggest possibilities that they cannot themselves contain.

Bibliography

9-11: Artists Respond (Milwaukie, Oregon: Dark Horse Comics, 2002).

Karl Kelly, “CCI: Frank Miller Reigns ‘Holy Terror’ on San Diego,” Comic Book Resources, http://www.comicbookresources.com/?page=article&id=33550, July 21, 2011.

Heidi MacDonald, “Crime, Comics and the Movies: PW Talks with Frank Miller,” Publishers Weekly, http://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/authors/interviews/article/27434-crime-comics-and-the-movies.html, March 7, 2005.

Frank Miller, “Anarchy,” http://www.frankmillerink.com/2011/11/anarchy, November 11, 2011.

Frank Miller, The Dark Knight Returns (New York: DC Comics, 1986).

Frank Miller, The Dark Knight Strikes Again (New York: DC Comics, 2002).

Frank Miller and Dave Gibbons, The Life and Times of Martha Washington in the Twenty-First Century (Milwaukie, Oregon: Dark Horse, 2009).

Frank Miller, Holy Terror (Burbank, California: Legendary Comics, 2011).

Frank Miller and Dave Mazzucchelli, Batman: Year One (New York: DC Comics, 2005).

Frank Miller and Bill Sienkiewicz, Daredevil: Love and War (New York: Marvel, 1986).

Frank Miller, Sin City: The Big Fat Kill (Milwaukie, Oregon: Dark Horse Comics, 2005).

Frank Miller, Sin City: Booze, Broads, and Bullets (Milwaukie, Oregon: Dark Horse Comics, 2010).

Frank Miller, Sin City: The Hard Goodbye (Milwaukie, Oregon: Dark Horse Comics, 2010).

Frank Miller, Sin City: That Yellow Bastard (Milwaukie, Oregon: Dark Horse Comics, 2005).

Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons, Watchmen (New York: DC Comics, 1987).

Miller probably thinks he’s doing right by women one way or another.

He also seems particularly taken with heart-shaped love nests-beds. Elektra is seen lying in one in Elektra Assassin and so are Goldie and Marv in the first Sin City. I don’t know if Miller thinks every woman is a “whore” but he probably feels like a woman looks best when dressed like one. He might even see it as empowering – some kind of not so secret weapon which brings men to their knees.

Might not be that much of a conflict there as Noah demonstrates with Wonder Woman and her love of bondage.

http://harkavagrant.com/index.php?id=311

Thanks for reminding me of that Kate Beaton; I think I’ve seen it before, but it still cracks me up.

I think it’s a good summary of my own skepticism about reading Miller’s work as particularly feminist. I think he likes strong women, and there’s some masochistic investment as well, and those things can go along with feminism (I think they do in Marston/Peter’s WW). But they don’t have to. I think that feminism often requires an explicit ideological commitment, which, as you say, Miller doesn’t have.

Oops; missed Suat’s comment.

I have a sort of lengthy section in my book (coming in 2015!) where I talk about the way that masochism and fetishization of strong women doesn’t have to be feminist. Masoch had really vacillating feminist commitments, for example, but Venus in Furs ultimately takes a strong antifeminist stand.

The folly of man’s efforts to control woman is something of a going theme in Miller’s work. Daredevil can’t control Elektra despite his efforts… He can’t make her stop killing for money and he can’t bring her to justice. Same goes for the Kingpin as described in the article, same goes for a lot of the Sin City I’ve read. What women do consistently offer to men in these comics is comfort followed by pain (see Elektra, Karen Page, Wonder Woman). Given all this, the fact that Miller’s sex workers so often do double duty as hookers and dominatrices suggests he sees women as bad mommies, which is a pretty dull view indeed.

> “With some gentle coaching from Dr. Mondat, Cheryl has managed to spell out a word using a child’s blocks. The word she spells is “XKAYP” — escape.”

I think the reference to “Cheryl” in this passageis supposed to be “Vanessa.” Right?

Osvaldo — crap, yes! Noah — please correct.

I wouldn’t really call it masochism, since the women don’t dominate the male heroes. But yeah, he does seem to have a sexual fetish for sweaty, muscular women spouting pulpy tough-guy talk while murdering large numbers of people. Not quite as charming as Crumb’s love of conquering big-butted giantesses or Eric Stanton’s fetish for losing co-ed wrestling matches, in my opinion.

The question of “strong female characters” is worth exploring, and that comic is hilarious.

However, my argument isn’t “Frank Miller writes strong female characters.” Instead, it’s that these stories are mostly about tough guys running around doing stupid shit, but their macho adventuring seems, at best, incidental to the solution and more often just makes things worse.

Miller’s own attitudes, intentions, and interpretations aren’t really central to that argument, either (as I tried to make clear in the conclusion). So, sure — masochism, fetishism, “bad mommies,” etc. — but that doesn’t really get at the point I was trying to make. And anyway, I think those elements are much stronger in the Sin City stories than in Love and War.

Hi Kristian,

I realize my comment was somewhat beside the point of the article, and that the argument doesn’t hinge on Miller’s psychology. And I don’t disagree with your argument about Miller’s depiction of tough guys. But I do think there’s a male-female dynamic in those comics that makes a reading of Miller’s text as as feminist hard for me to swallow, even a highly qualified one like your own. For example, in “Love and War” the Kingpin’s failure to keep his wife strikes me as less than a statement about the articulation of desire than it is about the power of forgiveness (in keeping w/Daredevil’s catholic themes), or more likely the theme I mentioned earlier, which is that man’s weakness is woman (for in Fisk’s world, kindness is weakness). That having been said, I think your argument is an interesting one, and well thought and written, too!

Error’s fixed; sorry about that!

hmmm Love and War used to be one of these books I’d try to read every 4 or 5 years just to find it’s still as disappointing as ever. Maybe it’s time to try again. Thanks so much for this article … I just can’t give up the idea Miller’s comics are smarter than him.

Kristian, the Kingpin is “Wilson,” not “Winston.” But a great essay, regardless — and meticulously sourced, which I always find truly admirable.

Corrected! Thanks, John.

John- Thanks for the edit. (I’m usually better at that sort of detail.)

Tim- I love the “Miller’s comics are smarter than him” line. That’s really what I was trying to get at in my conclusion, and you put it much more neatly than I managed to. I wonder, though, why you find Love and War (in particular) so disappointing. It is my favorite of Miller’s books. That probably has more to do with Sienkiewicz’s art than anything else. But still, there are a couple really great moments there. One is the sunset image, with the knight and the lady, just when Victor is killed. The other is the scene of Wilson looking at Vanessa’s photo just after he’s realized what she needs. Those two scenes are enough, I think, to make the book really worthwhile.

Nate- I wonder if you could elaborate on the point about forgiveness. And I think I disagree about “man’s weakness [being] woman” and “kindness [being] weakness”; or at least I partly disagree. The doctor, for sure, sees Vanessa as making Wilson vulnerable, and explicitly decides to use her as a “weapon.” But Fisk’s actions seem to undercut that strategy, since it turns out he cares more about her being well than about her being his. I’m not sure if the Kingpin thinks that his love for his wife makes him weak, but I think the story suggests otherwise. His decent treatment of her, despite the pain it causes him, would seem to demonstrate strength.

Kristian, no worries. Haste, like love, makes fools of us all. But sometimes it has to get done, anyway. I’ll probably have at least one glaring typo in this comment.

I’ll jump in with an opinion before Nate answers with his. I think Fisk’s feelings about his devotion to Vanessa must be even more complex than that — maybe the weakness from which he derives strength, or maybe just the part of his life wherein he is a decent human being, without which he’d kill himself — that scrap of meaning to which he desperately clings. I actually never read Love and War, but Miller is consistent in how he treats that relationship, so I’m familiar.

My favorite Miller Daredevil is “Born Again.” For me, that book is a joy. I think I’ll read it again!

I really just mentioned forgiveness because it seemed like an alternate reading (not necessarily one I’d get behind), in which Kingpin has the capacity to let go despite his evil… A kernel of human kindness or something. This sets him apart from the more psychopathic characters that Daredevil encounters. As for man’s weakness being woman, I think that if we grant Kingpin’s capacity to control everything around him (which he does in this book and in every other Miller depiction of the character), then it’s hard not to see his letting go as an admission that in this one case, he just can’t get what he wants. And even if it is motivated by his love for her well being and lets her go because of that, well, I think that says more about his capacity for love than it does her strength as a character, or her agency.

Nate- That’s pretty interesting. I think we need to consider, though, how the story the Kingpin tells himself (about himself) differs from those the other male characters tell themselves. Wilson Fisk does not think of himself as a hero or as Vanessa’s savior. The book begins by contrasting his power in the world with his helplessness in the face of whatever troubles his wife. Of course Wilson is more powerful than Vanessa, but he doesn’t wish, intend, or recognize the way that power imbalance shapes their relationship. It is not just the fact that she wants to escape, but the realization that she feels there is something to *escape* from (as opposed to merely leave) — that she is afraid of him — that hurts Wilson so deeply. Vanessa’s strength of character is demonstrated by the fact that she does articulate what she wants, though it obviously terrifies her to do so. His is shown by the fact that he respects her agency, though no one could force him to. What I’m arguing is that the thing that allows him to behave decently is precisely the fact that he is not a hero, even in his own mind.

I think that fits pretty well with John’s point above, about that relationship providing a kind of sanctuary where the Kingpin can behave like a human being. Of course that view still takes for granted a patriarchal framework, with a division between the (male) world of business and politics and the (female) domestic/emotional sphere. I suppose that complicates — or perhaps, limits — the feminist interpretation, but I don’t think it defeats it. After all, the point is not that Wilson Fisk is a model feminist, but that the story offers a critique of hero stories, within which Fisk provides a foil for the other male characters. In other words, the values by which his action is measured within the story are largely (though not perfectly) feminist, whether or not Fisk’s outlook is feminist in itself.

If anyone is interested I made a handful of similar points about the Daredevil book in an essay I recently published, along with a defence of “Void Indigo”…

http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/21504857.2013.860378#.UyHWcV6QHyA

Kristian,

I get where you’re coming from, I think, though I’m not quite sure what you mean when you call Fisk a foil. Do you mean that he’s the only person capable of recognizing that Vanessa is a person, and not merely a possession? If so, then I suppose he’s more feminist than her kidnapper. But I’m not sure that makes him more feminist than Daredevil, who never has a chance to acknowledge her agency one way or another. It seem like the more defensible argument for Miller’s unintentional feminism is in her capacity to frustrate the expected role of “damsel in distress.” That said, her self-assertion is, in the ended, granted by a man, which to my eye sort of undercuts that. But as they say, “reasonable people can disagree.”

Nate,

A few points, which may or may not clarify what I’m saying:

Cheryl, in killing Victor, breaks out of the Damsel in Distress role that both Victor and then Daredevil (and then Victor again) have cast her in.

Vanessa’s position is very different. Not only is there a real power imbalance between her and her husband, but she has suffered a loss of agency at the psychological level. She’s completely withdrawn, practically catatonic. The Kingpin’s whole project with the kidnapping plot is to find a way that she can regain her agency; and when she does, he respects it. It’s pretty likely that he knows going into it that she will leave him, since he says early on that he is going to “commit an act you will never forgive.” I think that focus on her agency, as opposed to his own, makes Wilson’s plot fundamentally different than either Victor or Matt’s attempted “rescues.” (On reflection, though, the doctor’s decision to use Vanessa as a “weapon” does pretty neatly mirror the Kingpin’s decision to take Cheryl hostage.)

Of course we should also remember that it is the Kingpin who is responsible for Victor kidnapping Cheryl in the first place. But at least Wilson Fisk doesn’t think that his actions make him a hero; he doesn’t play moral make-believe about what he’s doing. And I think that sets us up for the book’s startling anti-climax. At the point where we expect him to be the most vicious, he actually behaves quite decently. That anti-climax calls into question the conventions of the genre, and forces us to contrast the story that Miller is telling us with the story that we were expecting to be told, the kind of story that Victor and (presumably) Daredevil tell themselves.

Again, my point is not that Fisk (or Miller, or anyone) is a feminist, or even just a good guy. (Fisk isn’t; I don’t know about Miller.) My point is that this story pushes against some of the conventions governing how these stories go, and that the conventions it most clearly challenges are sexist — which, I think, makes the story feminist, at least in part, and if only by default.

Ah I get it… I mean, I already got that you weren’t arguing that Miller or the characters were feminist or good guys, but I was having trouble seeing Fisk’s role in her recovery of agency (in fact, his role in the kidnapping slipped my mind). With that in mind, I can better see your argument about agency. Thanks for the clarification!

Click bait for corporate shill trying to fill google with bogus content now that the world is starting to recognize the cancer that is Frank Miller. Fake article, bought and paid for. Welcome to the age of Google wanks.

Pingback: Open Thread and Link Farm, Friendly Face Edition | Alas, a Blog