The Walking Dead, the most popular show on television, has made a name for itself being a dark, cinematic, and wildly successful story about a zombie apocalypse on the cable leviathan AMC. And with numerous accolades from mainstream industry awards like the American Film Institute (twice), the People’s Choice Awards, the Television Critics Association, and even a Golden Globe nomination, a rare feat for any science fiction or horror series, it’s become a juggernaut franchise any network would envy. It has become so popular, in fact, that AMC dedicates a full hour of its schedule to a live post-show analysis hosted by Nerdist mogul Chris Hardwick called The Talking Dead, and featuring a wide range of celebrity fan guests.

But, I hope, for all its achievements critics may one day remember the franchise not solely for its popular success, but rather in its ability to build empathy for real-world survivors of tragedy.

Science fiction at its best allows us to tell stories about the world in which we live in ways that transcend politics and prejudice. Fantastic elements like zombies, aliens, or supernatural monsters all carry elements of our deepest fears and anxieties about the world we live in. And through these devices we can deal with human issues like guilt, redemption, or morality in safe, palatable ways while providing seemingly mindless entertainment for the masses.

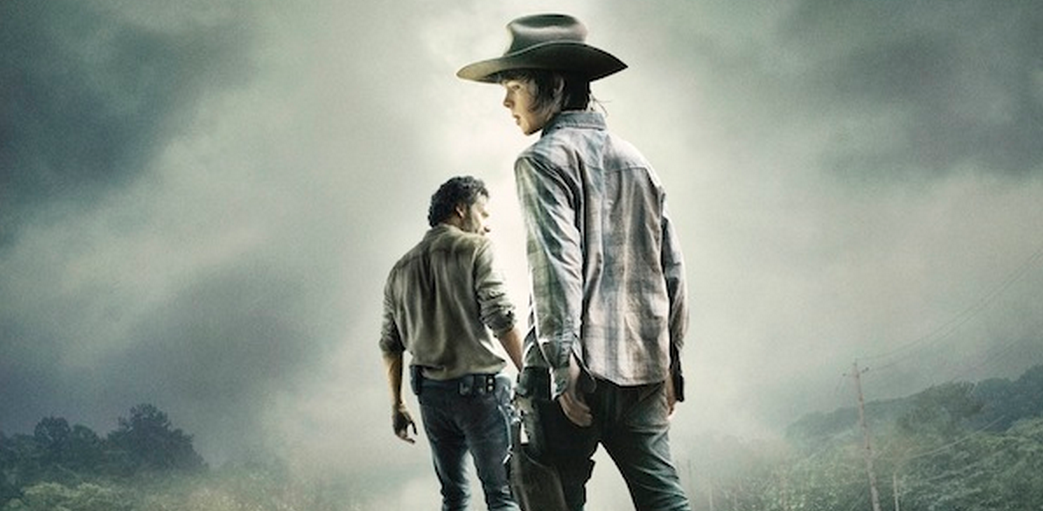

The Walking Dead is set in contemporary Georgia shortly after a deadly epidemic has lead to the complete downfall of civilization. A former sheriff, main character Rick Grimes, played by Andrew Lincoln, navigates through devastated suburban landscapes filled with “walkers” (the word zombie is never mentioned), the reanimated dead who seek only to consume the flesh of the living. Rick, his wife Lori and son Carl join with other survivors in risking ravenous encounters with walkers to find temporary shelters and clean food. Contact with other humans carries its own dangers as some groups make it clear they would rather steal, rape, or kill to just to give themselves an advantage for another day. The world of The Walking Dead is rife with desperation, not unlike current war zones in Central Africa and Syria and natural disaster regions in Southeast Asia.

In 2012 Sarah Wayne Callies, who played Lori, became a Voice for the International Rescue Committee. Last year she joined a campaign to raise awareness for Syrian refugees, visiting with survivors of sexual violence in Domiz. Although she hasn’t made any direct parallels from her humanitarian advocacy to the problems her character faced, the similarities are there for anyone who watches the show.

In the second season, when Lori discovers that she is pregnant, she wrangles with the decision of whether or not to abort the child. Is this the kind of world she wants to bring a new life into? She fears for more than just her children’s safety, dreading that her son’s quick adaptation to their new reality means he will lose his humanity. In the episode “Killer Within” she begs Carl not to lose his pre-apocalyptic sense of right and wrong, pleading “don’t let the world spoil you.”

The theme of psychological trauma in children also continued this season, coming to a dramatic head in perhaps the show’s most shocking episode yet, “The Grove.” I won’t spoil it for you, but let’s just say we can take solace in the fact that children in our world do not have to suffer alone and psycho-social services can be available.

Actress Danai Guirira, the katana-wielding Michonne, is also no stranger to the refugee narrative. Born to African immigrants in the US, she grew up in Zimbabwe and has been vocal about the unique experience of Africans. Danai is also co-founder of Almasi Collaborative Arts, an organization that fosters cooperation between American and Zimbabwean artists and empowers Africans to tell their own stories. Her professional encounters with Liberian women in war certainly influence her portrayal on screen. “The parallels of The Walking Dead world and a war zone– that idea was very resonant for me,” she told Rolling Stone last fall.

The show’s fourth season became even more poignant in depicting the plight of its characters in a way that rings true to real-world crises. After our heroes set up a permanent settlement, the story moves away from conflicts with other survivors. Instead they must focus on growing their own food, collecting clean water, continuing their children’s education, substance abuse as a coping mechanism, and combating a serious outbreak of disease in their new home.

The character of Hershel, played by veteran actor Scott Wilson, is the embodiment of a peacebuilder. He inherited the role of the group’s conscience following the exit of another white-haired elder, Dale, who functioned as a more explicit voice for justice and human rights. While Rick and Michonne struggle with opening themselves up to help others, afraid of the pain that will come when they ultimately fail, Hershel is an unending fountain of mercy. During the plague storyline he gives an impassioned plea for the afflicted to bear together. “You take a drink of water, you risk your life,” he he says. “The only thing you can choose is what you’re risking it for.”

In the episode “Internment,” Hershel endeavors to give the infected hope and comfort, referencing John Steinbeck’s quote about a sad soul killing faster than any germ. It is in contrast to others in the group who want only to separate the sick from the healthy, and even one character who took murderous measures to keep the disease from spreading. While waiting for treatment to arrive — and there is no guarantee it will — he exposes himself to the plague to bring food and water and even hand pump oxygen into a man’s lungs. Compassion fatigue? This man has never heard of it. As we see everyday in the stories of real-life refugees, Hershel stands out because of his resilience: stuck in a dire situation, his character shows that there are still those who rise to take care of others

It is a story not unlike a real life doctor in Somalia, Hawa Abdi, who turned her family’s farmland into a camp for over 90,000 internally displaced persons. She and her daughters work hard not only to feed and provide medical care for these people, but also to protect them from further violence and exploitation at the risk of her own family.

Logically, The Walking Dead’s themes come from the evolution of decades of television storytelling. Social and political issues have always had a place in science fiction. It was the original Star Trek series that set the precedent in America for the genre to do more than just entertain. At a time of social upheaval in the 1960’s, the series boldly represented humanist ideals of equality and social justice. While the show was slow to hit its peak, its journey from a short-lived television series to a massive media empire is what paved the way for socially responsible and commercially successful science fiction in America.

As audiences developed a taste for grittier dramas more grounded in the real world, science fiction film and television continued to keep pace. More recent ventures that tackle global issues with great commercial and critical success include Battlestar Galactica (2004), District 9 (2009), and Catching Fire (2013).

The Peabody Award-winning Battlestar Galactica had a similar post-apocalyptic survival set up, but with humans battling an advanced race of robots. Producers Ronald D. Moore, an alumnus of the Star Trek shows of the 1990’s, and David Eick mixed themes of the scarcity of basic human needs like clean food, water, and medical care with much more provocative nods to hot button American political issues like torture, terrorism, and the occupation of Iraq. Eick and Moore appeared alongside stars Edward James Olmos and Mary McDonnell at a special UN panel on the show’s themes of war, dialogue and reconciliation, and human rights in 2011.

Neill Blomkmap’s District 9, an insectoid alien version of apartheid South Africa, received four Academy Award nominations including Best Adapted Screenplay and Best Picture. Blomkamp followed his debut with another overtly political story with Elysium, about a future Earth where humans are violently divided by access to healthcare and economic disparity.

Catching Fire, the sequel to the powerhouse teen sensation The Hunger Games, took a deliberate darker and more political turn into the series. Katniss Everdeen, played by Oscar winner Jennifer Lawrence, is a reluctant symbol of a resistance against a brutal totalitarian regime. Her motivation, to keep her loved ones safe, is so simple that she could represent the voices of any number of people power movements.

The creator of the comic book series and showrunners of The Walking Dead have never mentioned any global inspiration for the stories they tell. But familiarity with refugees isn’t a requirement for telling a compelling, human story about real people who have lost everything and still persevere. American popular media is in dire need of stories that help us build empathy with the rest of the world, and science fiction dramas like The Walking Dead, that feature realistic storylines and a diverse cast and crew, can help fill that void.

_______

Christa Blackmon is a graduate of American University and the former Senior Editor of Palestine Note. She is currently a freelance writer on peace and conflict issues in Washington, DC. You can find her on Twitter at @theodalisque.

While I agree that it is some of the relatively quiet moments of this show that I really enjoy (not that I don’t also enjoy some zombie-killing action) like dealing with the swine flu and even the time on the farm in Season 2 that most fans seem to have hated, I am skeptical of the assertion that “Science fiction at its best allows us to tell stories about the world in which we live in ways that transcend politics and prejudice.” Even at “its best,” sci-fi can never be disentangled from the politics of time and place and there are lots of troubling aspects of this show, despite the fact that I watch and enjoy it. It’s treatment of race has gotten a little better in the most recent season (though they are turning Michonne from angry black woman into a sword-wielding mammmy), but the southern setting makes the stilted way it has dealt with race all the more stark.

Politics can never be divorced from the issues you say the show brings up or reflects on because they are deeply embedded in the causes and perpetuation of those conditions – even ostensibly “mindless entertainment.” Universalizing is dangerous.

While I’d like to think that Dale or Hershel’s lessons are the ones viewers are learning, I don’t think the narrative actually favors their way of doing things and actually encourages a belief of the post-apocalyptic as a state of exception in which all violence is justified and actually blurs the line between the living and the walking dead.

If anyone is interested I have written a bit about The Walking Dead (both the TV show and comic):

Where ‘The Walking Dead’ Fails Viewers When It Comes to Race

The Walking Dead & The Apocalyptic Open (about the comic)

“This Sorrowful Life” – Making Time to Redeem Racists

Great points!

The transcendance of sci-fi above politics is more of an optical illusion. TWD certainly can’t be disentagled from (racial) politics, but of the franchises I mentioned it is the most apolitical.