I’m looking at DC’s newest character, Equinox, a teen superheroine based on Cree activist Shannen Koostachin. She’s a member of Jeff Lemire and Mike McKone’s Justice League United. Like Marvel’s Alpha Flight, the team is Canadian, so the character continues the U.S. publishing tendency to place Native America outside of U.S. borders. But I see some promise here: Equinox is from an actual tribe, her costume isn’t red, her features aren’t cartoonishly “Indian,” and she’s not showing any thigh or cleavage. That helps offset the “her power stems from the Earth” cliche, and I actually like the idea of a character who will have different abilities as the seasons change–never heard that one before.

But will she be better than Wyatt Wingfoot? He was born in Fantastic Four No. 50, cover-date May 1966 , on newsstands a month before my June-issued birth certificate. Wyatt’s dad is “Big Will Wingfoot – the greatest Olympic decathlon star this country ever had!”Here on Earth-1218, that’s James “Big Jim” Thorpe, gold medalist for the 1912 Olympic pentathlon and decathlon. Stan Lee even gave his name to the college coach trying to draft Wyatt: “I’m sorry! I’m not interested in athletics, Coach Thorpe!”

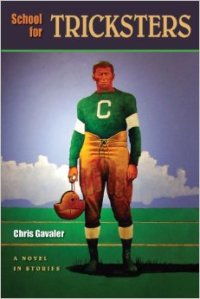

Jack Kirby penciled the issue, but I prefer Sante Fe painter Ben Wright’s Thorpe rendering. I picked “Jim Thorpe in His Carlisle Indian School Football Uniform” for the cover of my novel School for Tricksters. Wright’s website says he “draws from Native American ceremony, symbolism, and tradition” and identifies him as “part Cherokee,” rarely promising signs. But I like the painting because the old-timey helmet sets the period, plus his slightly stylized Thorpe looks really cool. The big “C” on his chest could be a superhero’s. Carlisle Man!

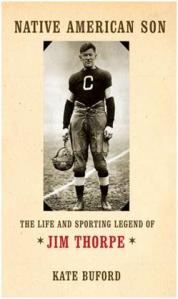

Biographer Kate Buford later told me Wright got it wrong. The cover of her Native American Son: The Life and Sporting Legend of Jim Thorpe features the original photo with an inside caption: “Jim Thorpe with the Canton Bulldogs, c. 1920, Canton, Ohio.” So the “C” is for Canton, a team Thorpe played for after his career peaked. Ben painted over the facts—the way lesser-known inker Joe Sinnott thickened Kirby’s lines for FF 50.

School for Tricksters is a historical novel, so I paint over a shelf of facts too. My daughter’s 11th grade history teacher capped a recent Carlisle Indian School lesson with “Oh, I’m sure those kids must have wanted to be there,” so my daughter grabbed a row of books from my office to write a rebuttal for her research paper. I recommended Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance: The Glorious Imposter. I used to exchange emails with the author, Donald Smith, up in Alberta. Thorpe is the School’s most famed student, but I prefer the adventures of Chief Buffalo Child, AKA Sylvester Long. He’s the real Carlisle Man.

The School railroaded children from their western reservations to the middle of Pennsylvania to be transformed into working class mainstream Americans. According to Long’s autobiography, he was born a full-blood Blackfoot in a great plains teepee, and so an ideal student for the program. Except that his birth certificate says Winston-Salem, NC, and both his parents were ex-slaves. Which still makes him the ideal Carlisle student, since Carlisle was all about painting over facts. The real-life dual-identity Long graduated to Hollywood, where he played another version of himself–until the movie exposure lead to his unmasking and suicide.

Sylvester, a mild-mannered library janitor, longed to be exceptional—a supeheroic dream for a mixed blood Clark Kent in the Jim Crow South. But did he just doodle over his real self or did he become his disguise? When Dean Cain proposed to Teri Hatcher on the season two finale of Louis & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman, the network shot three answers: “Yes,” “No,” and “Who’s asking, Clark Kent . . . or Superman?” They were trying to prevent the “real” answer from leaking before the show aired. Smith documents at least a dozen Lois Lanes in Long’s adventures, but no marriage proposals. His identity wasn’t stable enough to settle down.

I ask my students the same question when analyzing superhero texts: what is the character’s core identity? I suggest four options: A) the superhuman, B) the human, C) neither, or D) both. For decades, Superman’s answer was “A.”Clark Kent is just the pair of fake glasses he wears around humans (David Carradine gives this a great monologue in Tarantino’s Kill Bill). But that flips to “B” after the 80s reboot. Clark lived a perfectly normal childhood until his superpowered puberty made him hide behind a cape and tights.

Sometimes students go with “C,” arguing that both Clark and Superman are public faces worn by an inner Kal-El. It’s a common idea outside of comics, that we all have a secret private self who transforms according to context: home, work, frat party. It fits the standard master-of-disguise trope too. Long could have wandered downtown any of his free Saturdays and leafed through a copy of Nick Carter Detective Weekly at a Carlisle newsstand in 1912. The old banner illustration is a row of heads, “Nick Carter In Various Disguises,” with the largest and literally central self right there in the middle.

But “D” is the most daring choice. What if the center doesn’t hold and we’re all just a series of shifting performances? Zorro admits as much when he unmasks himself as the languid Don Diego. The costume wasn’t just a disguise; it made his whole body come alive—something Bruce Banner and the Hulk understand too. Are any of us really the same person when we’re angry? And is the goal to find a “golden mean” as Don Diego promises his fiancé? Like Teri Hatcher, Lolita is no polygamist. And yet who is the Scarlet Pimpernel’s wife married to? If Sir Percy is just a foppish disguise, why does he keep laughing that inane laugh even after he unmasks?

All that is too complicated an answer for early 20th century America. When they unmasked Sylvester they only saw a dual-identity fake. Except then why did a private detective have to write over the facts, claiming he fingered rouge and hair-straightening gel from the corpse? Long’s alma mater championed the dual-identity model too, doctoring “before” and “after” photos of graduating students. Sometimes you have to white-out a shirt collar to keep the world savage/civilized.

Big Jim’s white/not-white wife was a Carlisle student too. She and Jim lost their first child, James Junior, their only son. Kate Buford and I give dueling banjo readings ending with the death scene, proof that narrativized facts and fact-based fiction can get along just fine. Kate and I live in the same town too, and our books came out just weeks apart—coincidences even most comic book readers wouldn’t believe. Stan Lee invented the Keewazi Indian reservation for the Wingfoots and dropped Wyatt into the Human Torch’s college dorm. Johnny looks up at his hulk of a roommate: “Say, whatever they feed you at home, I’d like it on my diet!”

Wyatt is still wandering the borders of the Marvel multiverse. I think he’s tangled with the Kree a few times too–an alien race Lee and Kirby created a year after Wyatt and who have only a phonetic resemblance to Equinox’s tribe. Equinox’s alter ego, Shannen Koostachin, was only fifteen when she died in 2010, but Canada’s House of Commons unanimously celebrated her superheroic achievements:

“In her short life, Shannen Koostachin became the voice of a forgotten generation of first nations children. Shannen had never seen a real school, but her fight for equal rights for children in Attawapiskat First Nation launched the largest youth-driven child rights movement in Canadian history, and that fight has gone all the way to the United Nations.”

And now she’s made it to Justice League United.

Choice “D” is essentially one of several arguments I make in my dissertation. I contend that certain American authors’ obsession with using references to popular culture in a broadly considered “literature of becoming” (of which bildungsoman would be a subset, for example – so folks like Diaz and Lethem) helps trace out the possibility of several simultaneous mutually constitutive identities of which particular articulation are positionally asserted in different contexts. The incorporation of serialized comics’ structures and forms, along with their concern with the slipperiness of identity provide this fiction with a skein for exploring the arc of “becoming” without having to settle on a unified and essential identity at its conclusion.

I also write about how reference to pop music has its own way of doing this.

Also, I am pretty sure Wyatt Wingfoot was the first Native American character I ever came across in any popular media that was not a tomahawk-wielding, feathered-headdress type or a drunken down on his luck type. I have read quite a number of comics featuring Wingfoot, but always fear there are some issues I’ve missed where some writer has written him into some stereotypical role.

I think Wingfoot may be Stan Lee’s second Native character. One of Sgt. Fury’s Howling Commandoes my have been first.

And your dissertation sounds fascinating, Osvaldo. Is Ricky Moody’s Ice Storm on that list of obsessive pop culture referencing in coming-of-age stories?

I’d just like to point out that I had no idea Chris had written a novel.

Moody didn’t make it into the diss (except as a quick reference), because I am mostly concerned with texts that explicitly tackle race and ethnicity.

Though when I expand my work to look into constructions of whiteness I plan to return to The Ice Storm.

Oh, and I ordered your book!

Thank you!

Osvaldo — I don’t think depictions of Native Americans in traditional garb is automatically a “stereotype.” It can be, if it’s inaccurate in its context, or disrespectful, but feathers do not automatically equal stereotype.

R. Maheras – well, sure. . . But given the history of representation of Native Americans in comics I feel confident in asserting that that feathered headdress is most often used as a broad characterization of such characters.

Anyway, my own reference was to the fact that Wyatt Wingfoot was the first Native American character that I came across in comics that did not adhere to the stereotype. Shit, even Spirit from G.I.Joe, a contemporary paramilitary comic wore a headband, dual-pony tails and frilled pants and had a pet eagle because he was so “connected to nature” as a tracker and shaman.