“The true picture of the past flits by. The past can be seized only as an image which flashes up at the instant when it can be recognized and is never seen again. ‘The truth will not run away from us’: in the historical outlook of historicism these words of Gottfried Keller mark the exact point where historical materialism cuts through historicism. For every image of the past that is not recognized by the present as one of its own concerns threatens to disappear irretrievably.”

–Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History” (English translation Harry Zohn; Illuminations p. 255)

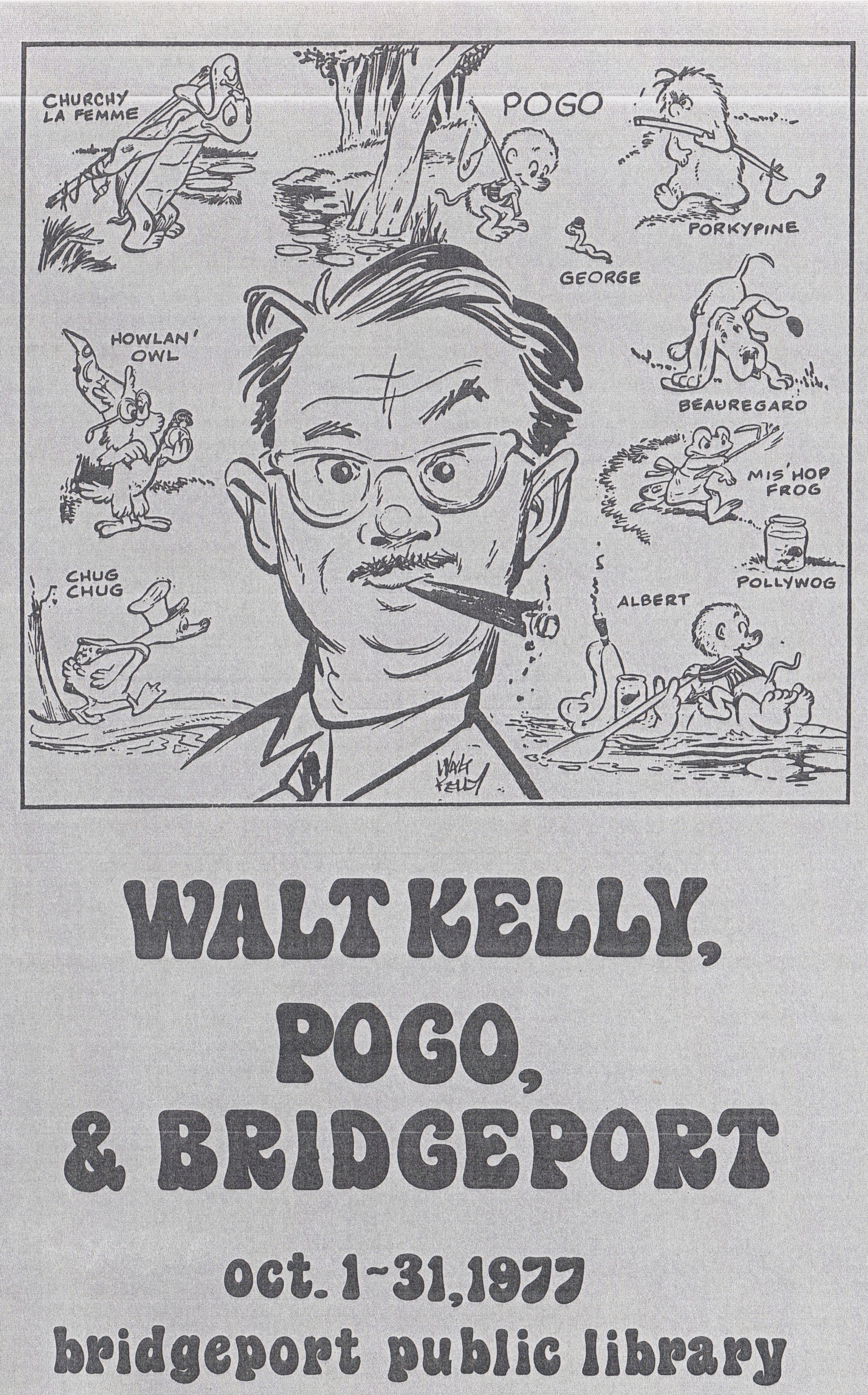

Fig. 1: Clipping courtesy of the Bridgeport History Center at the Bridgeport, Connecticut Public Library

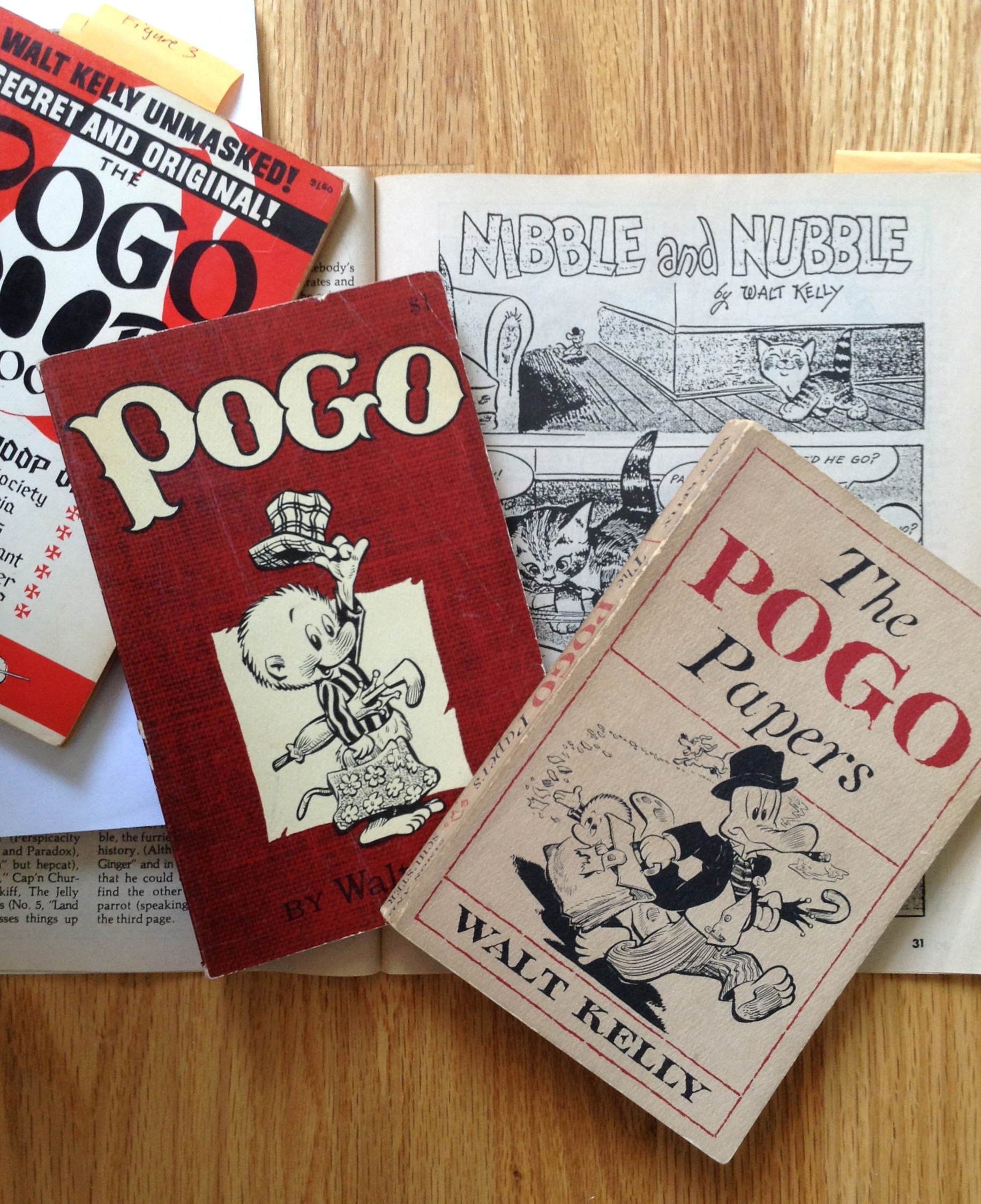

I wonder sometimes if I’m being followed. I can’t seem to escape from Walt Kelly. R. Fiore’s recent TCJ review of the new Hermes Press collection Walt Kelly’s Pogo: The Complete Dell Comics Volume 1, compels me once again to consider the cartoonist, who died in 1973 and lived his formative years in Bridgeport, Connecticut. The Park City is about thirty miles south of Oakville, my hometown, and Oakville is just outside of Waterbury, where the Eastern Color Printing Company began producing comic books in the 1930s. Of course, I’d heard of Kelly long before I’d read any of his work. He’s on a short list of Connecticut luminaries, along with Nathan Hale, Rosalind Russell, Paul Robeson, and Thurston Moore, but I didn’t read Kelly’s celebrated strip until I was in my mid-thirties. Several years ago, one of my students gave me copies of two of her late father’s beloved Pogo collections. I know you enjoy comics, she said, and you teach them, too, so I think you might like these: Pogo, the first Simon and Schuster collection from 1951, and The Pogo Papers, from 1953. Covers creased, paper tan and brittle, bindings cracked. Her dad, I know, loved these books, returned to them, left them behind for his daughter, for me. I thanked her for this kind gift, but even then, in the summer of 2007, I neglected them. A year later I was asked to contribute an essay to a collection on Southern comics and I remembered what my student had said: You might need these. I think that’s what she said. I’d like to think so, anyway.

I begin with what is probably more than you need to know about me and Walt Kelly because, like Fiore, I, too admire the artist, and, in the years since my student handed me her father’s Pogo books, I’ve written about his work twice: first, in an essay on Bumbazine for Brannon Costello and Qiana Whitted’s collection Comics and the U.S. South (UP of Mississippi, 2012) and again last year for a paper presented at the Festival of Cartoon Art at the Ohio State University’s Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum. In the first essay, which Tom Andrae cites in his introduction to the new Dell Comics collection, I discuss the two scenes Fiore addresses in his review— the watermelon panel from “Albert Takes the Cake” (Animal Comics #1, dated Dec. 1942-Jan. 1943) and the railroad sequence from “Albert the Alligator” (Animal Comics #5, dated Oct.-Nov. 1943). You can read that 2012 essay, “Bumbazine, Blackness, and the Myth of the Redemptive South in Walt Kelly’s Pogo” here or from your local library; the Google Books version does not include the illustrations.

Fiore takes issue with Andrae’s analysis of the black characters who appear in “Albert the Alligator.” While he begins with the suggestion that “Andrae is on firmer ground in denouncing the characterizations in the story from Animal Comics #5,” Fiore then asks that we consider other readings of the narrative:

Once again, however, [Andrae] is sloppy in characterizing [the characters] as “derisive minstrelsy stereotypes.” The conventions of the minstrel show were as formalized as the Harlequinade, and the characters in the story at hand don’t fit them. Further, I believe a more sophisticated and context-conscious reading would come to a different conclusion.

As I read these remarks, I began to wonder, what would a “context-conscious reading” of this sequence look like? And is Fiore correct? Would it reach a different conclusion than the one in Andrae’s introduction?

I attempted just that sort of contextual reading in my Bumbazine essay, in which I trace the impact not only of minstrelsy but also of the rhetoric of the South as redeemer, a concept Kelly inherited from the Southern Agrarians. But any reading that hopes to place Kelly in historical context must take into account the tensions and fractures that exist in his body of work. Kelly is a significant cartoonist not because he was more progressive than other artists working in the 1940s but because he records for us the contradictions in his own thinking and practice.

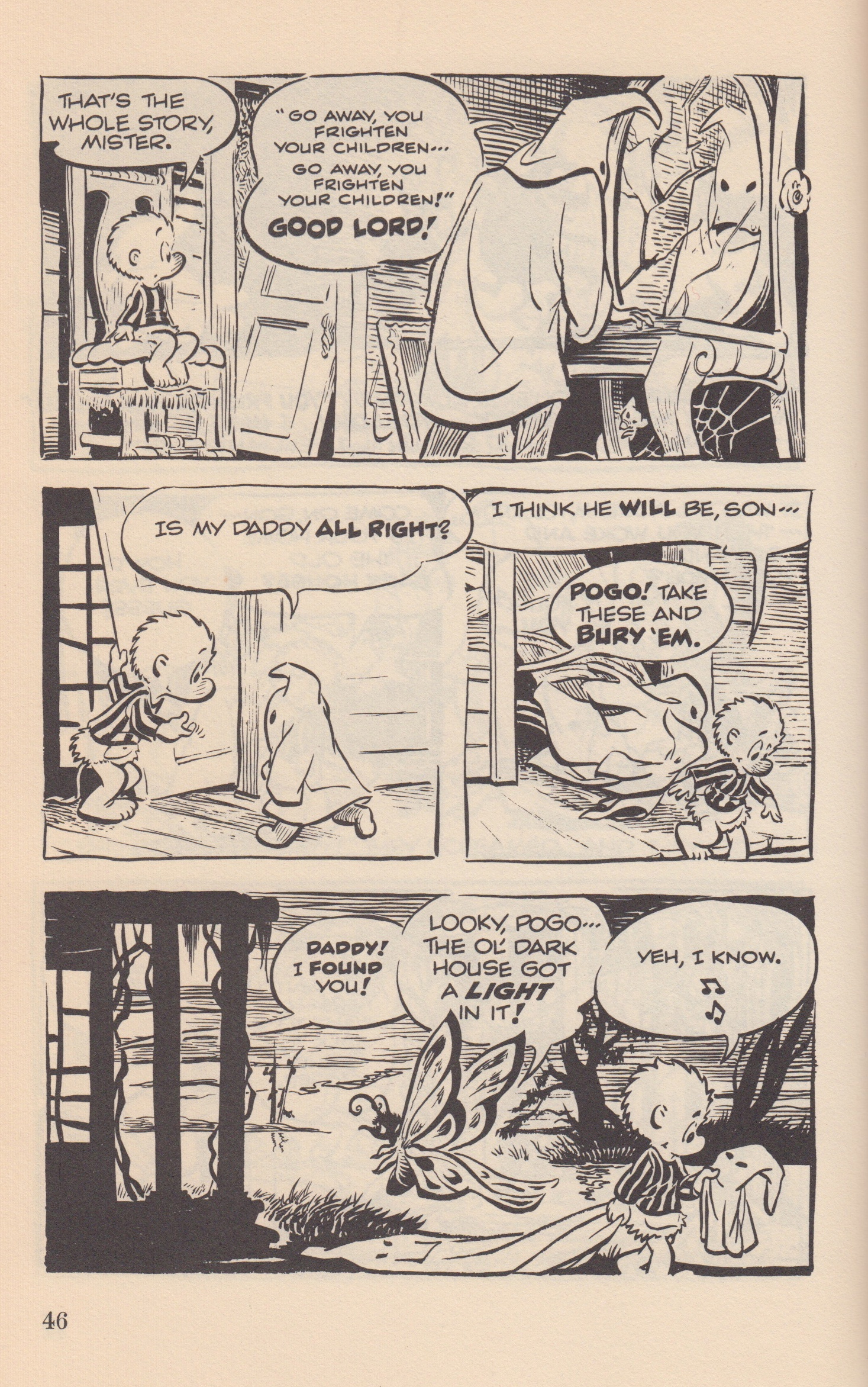

Fig. 2: Pogo takes on one of the Kluck Klams in a story from The Pogo Poop Book, 1966

Kelly, the child of working-class parents, a left-leaning, often progressive autodidact who, later in his career, would challenge Senator Joseph McCarthy, the Ku Klux Klan, and the John Birch Society, demands our attention because he forces us to ask another question: given his reputation as a cartoonist beloved by students and liberal intellectuals of the 1950s and early 1960s, how could he also have produced works such as “Albert the Alligator,” stories that clearly owe a debt to the conventions of the minstrel stage, and that traffic in derogatory stereotypes? To answer this question, I believe we need to understand Kelly’s nostalgia for his hometown of Bridgeport, Connecticut. One of the flaws in some of Kelly’s early work was his inability or unwillingness to interrogate the images and ideas he’d inherited from childhood artifacts such as, for example, Joel Chandler Harris’s Uncle Remus stories. As Andrae reminds us in the introduction to the Dell Comics collection, Kelly’s father enjoyed readings those stories to his son.

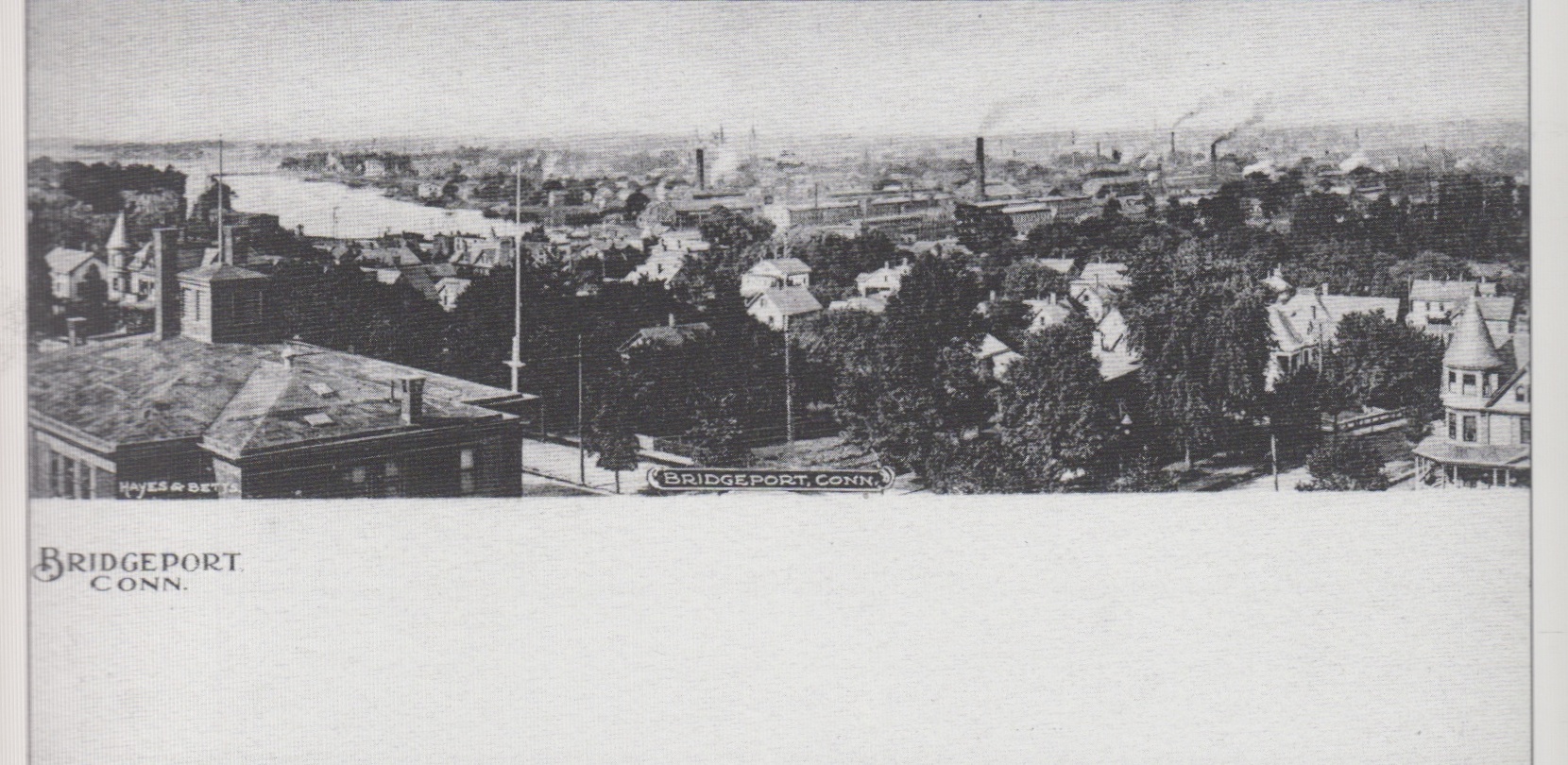

Fig. 3: Image of Bridgeport from Andrew Pehanick, Bridgeport 1900-1960, p. 124

What effect does nostalgia have on us, as writers, as artists, as critics—as fans? When I speak about Kelly, I find it difficult to separate my nostalgia for home from Kelly’s fondness for the Bridgeport of the late teens and 1920s. When I read Kelly now, I am reminded of my childhood in Connecticut, not because Kelly’s comics played any role in it, but because the setting he describes in his essays, for example—the industrial landscape of the Northeast—is also the world of my imagination. By the late 1970s and the early 1980s, however, the brass and munitions manufacturers that had attracted so many immigrants from Europe and migrants from the South were fading. The only traces that remained were signs with names like Anaconda American Brass on redbrick walls of abandoned factory buildings. And the stories, of course, of the men and women who, like Kelly’s father, like my grandparents and great grandparents, worked in those mills.

Fig. 4: My grandmother, Patricia Budris Stango, second from left, at work in 1941 at the United States Rubber Company, later called Uniroyal, in Naugatuck, Connecticut

As I argue in my essay on Bumbazine, Kelly did not write about the U.S. South. Rather, he told stories in a setting that, for all its southern trappings, looked and felt more like New England. The city of Bridgeport, Connecticut, was, in the early twentieth century, as Kelly describes it, “as new as a freshly minted dollar, but not quite as shiny. The East Bridgeport Development Company had rooted out trees and damned up streams, drained marshes, and otherwise destroyed the quiet life of buttercups and goldfinches in order to make a section where people like the Kellys could live.” In this essay from 1962, Kelly might be describing Pogo’s Okefenokee Swamp: “Surrounding us was a fairly rural and wooded piece of Connecticut filled with snakes, rabbits, frogs, rats, turtles, bugs, berries, ghosts, and legends” (Kelly, Five Boyhoods, 89).

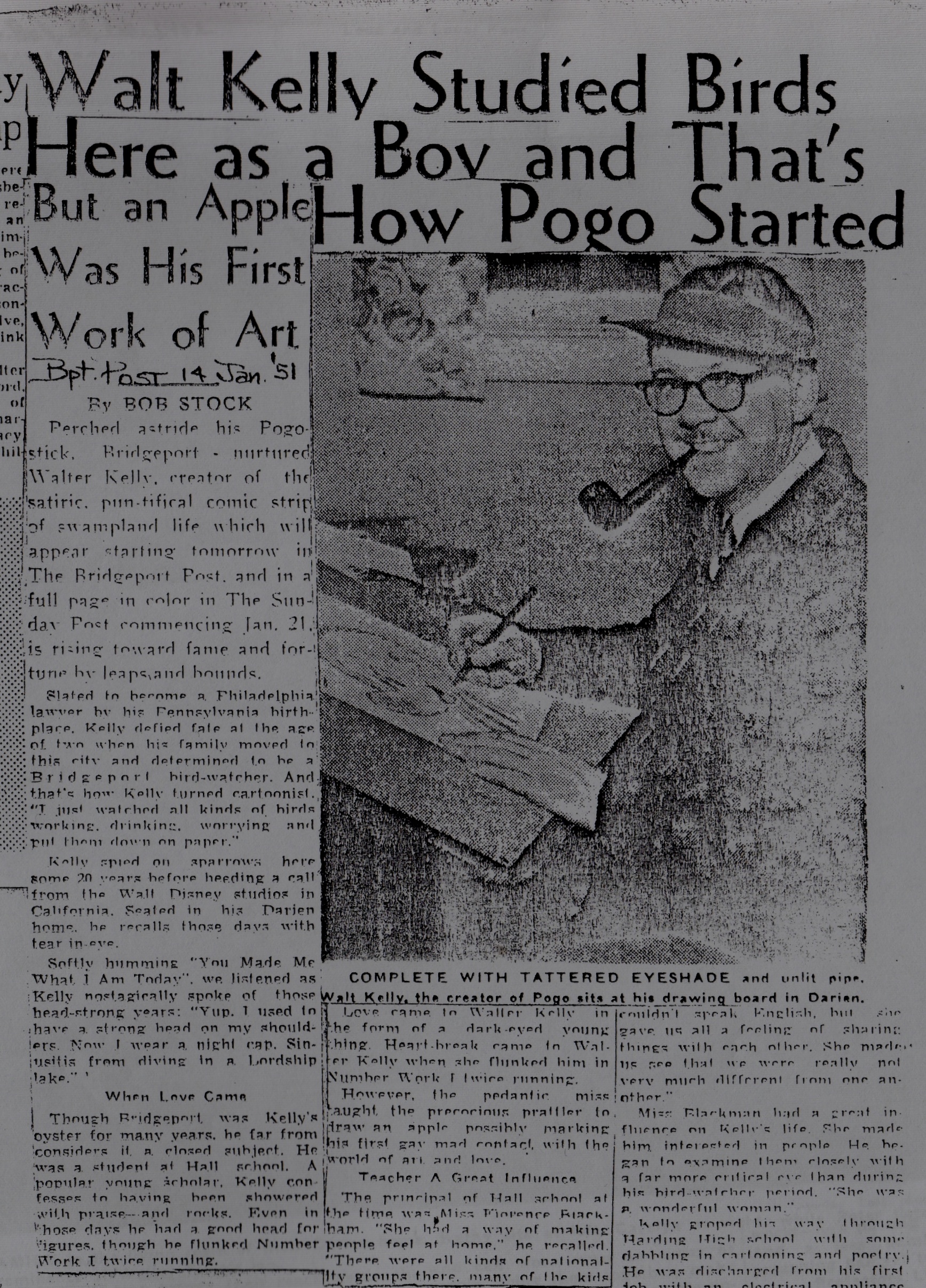

Fig. 5: Clipping from the Bridgeport Post, January 14, 1951. Courtesy of the Bridgeport History Center.

Kelly scholars from Walter Ong to Betsy Curtis to R.C. Harvey to Kerry Soper and Tom Andrae have since the 1950s been looking closely at some of these legends. In his essay “The Comic Strip Pogo and the Issue of Race”—along with Soper’s We Go Pogo (UP of Mississippi, 2012), one of the best academic analyses we have of Kelly’s strip—scholar Eric Jarvis points out that Kelly often referred to “his elementary school principal in Bridgeport as a rather nostalgic model of how society should approach these issues with ‘gentility’” (Jarvis 85). Jarvis then includes passages from Kelly’s introduction to the 1959 collection Ten Ever-Lovin’ Blue-Eyed Years with Pogo in which the artist again remembers the Bridgeport of his childhood and that principal, Miss Blackham: “Somehow, by another sainted piece of wizardry, she sent us off to high school feeling neither superior nor inferior. We saw our first Negro children in class there, and believe it or not, none of us was impressed one way or another, which is as it should be. Jimmy Thomas became a good friend and the young lady was pretty enough to remember even today” (Kelly, Ten Ever-Lovin’ Blue-Eyed Years, 6).

As Kelly biographer Steve Thompson reminded us at the OSU conference, however, in other interviews Kelly describes the racism and ethnic tensions in the Bridgeport of the 1920s. So, like Jarvis, I am fascinated by the role nostalgia plays in Kelly’s art and in his essays because, after all, as Svetlana Boym reminds us, nostalgia is a utopian impulse, a desire not so much to recover the past as it was lived but to recall the life we wish we’d lived, in a world that never was. But, if it had existed, what would that world have looked like? “Nostlagia (from nostos—return home, and algia—longing),” Boym writes, “is a longing for a home that no longer exists or has never existed. Nostalgia is a sense of loss and displacement, but it is also a romance with one’s own fantasy” (Boym XIII).

When Brannon Costello asked if I’d contribute an essay to Comics and the U.S. South, I hesitated. My first thought was to write an article on Howard Cruse and Stuck Rubber Baby. Already taken, Brannon told me. Then I asked, What about Pogo? You can’t publish a book on comics and the South without Pogo. A friend later remarked, Why would you write about the South? You lived there for less than a year, and the whole time all you talked about was New England. That’s not exactly what she said. What she said was something closer to this: You hated it there. But, more recently, when I told my friend that I’ve now written two essays about Kelly and the South, she smiled and said, Of course. The more we resist something, the more we are drawn to it. The more I resisted Kelly’s comics, the more I found myself drawn to them and to the South and to the myths of Kelly’s youth—my youth—that I had ignored

So, in reading R. Fiore’s review of the new Pogo collection, I again find myself face to face with Walt Kelly. And I keep returning to Walt Kelly’s early comics not because they transcend discourses of race; rather, I return to them because they include these stock figures and because I believe these early stories, like my student’s gift, offer an opportunity to think and to reflect on how these discourses—how these racist stereotypes—have shaped my life, my thinking, my conduct in the world. I am writing about Kelly because, to borrow a phrase from Walt Whitman, he and I were “form’d from this soil, this air,” and I turn to him because he invites me to dig through that soil, to breath the air again, to remember.

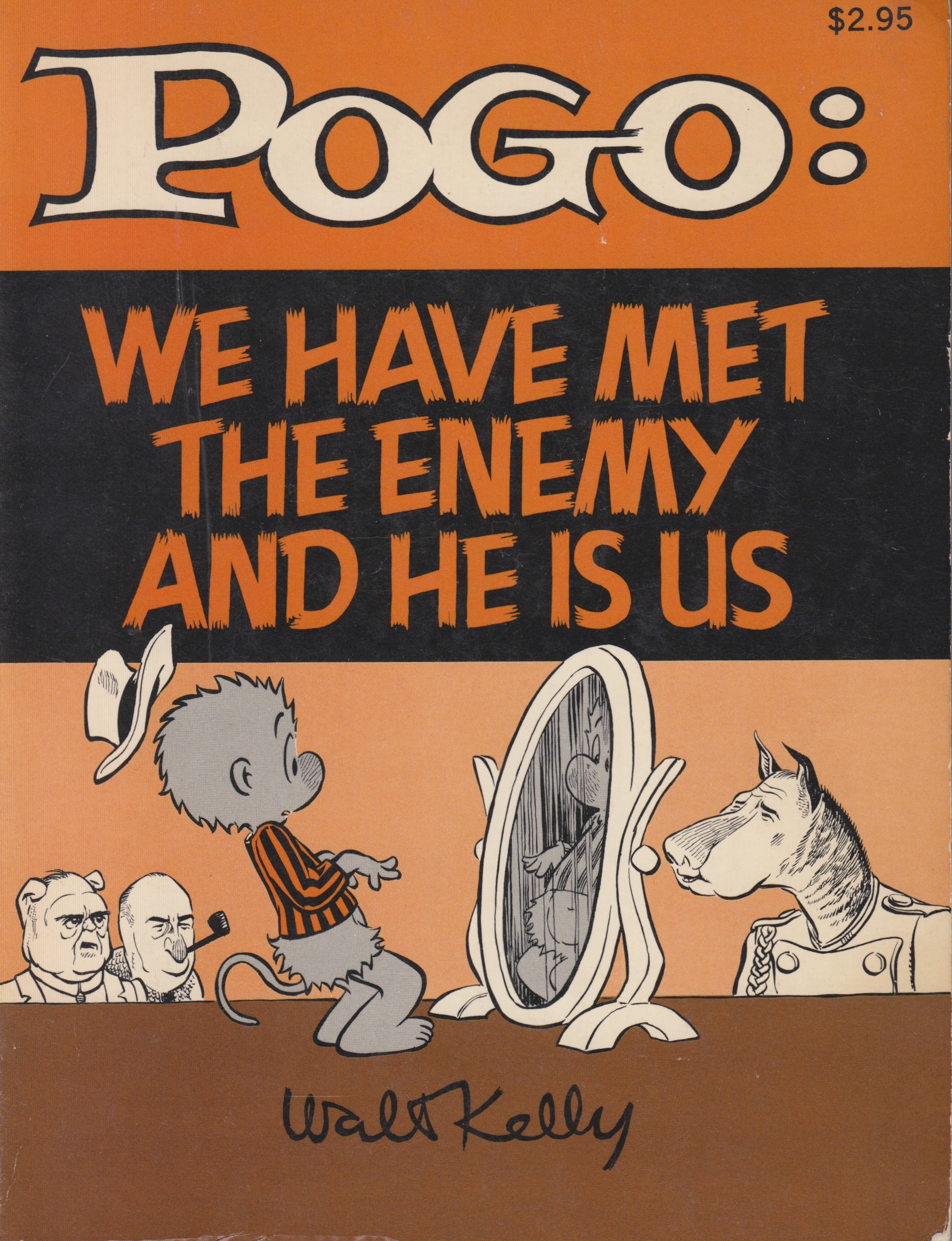

Fig. 6: The final Pogo collection Kelly published in his lifetime (1972)

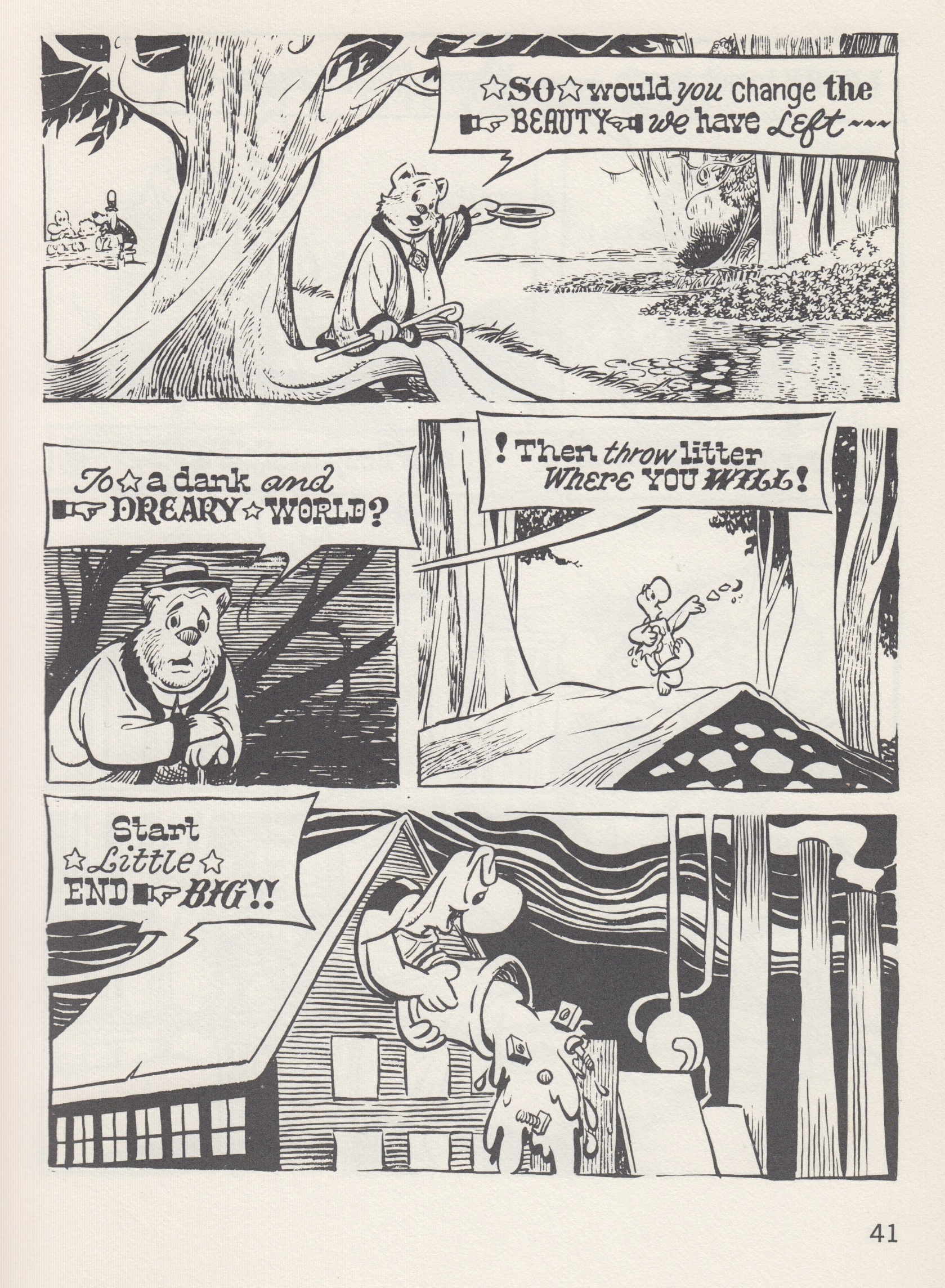

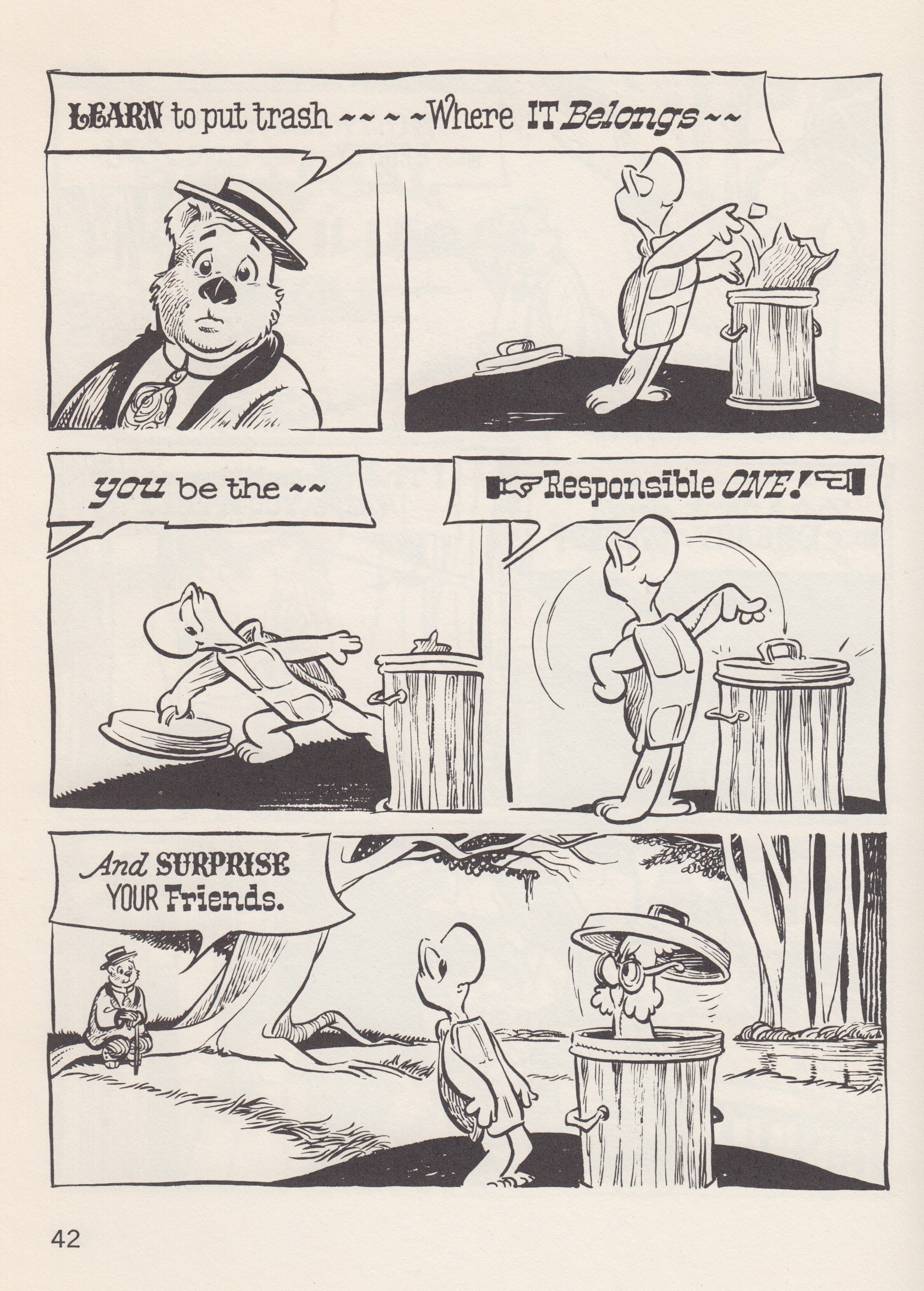

It is perhaps too easy to say that these early comics are a record of their time. They are, of course; they demand that we investigate and reconstruct the discourses of the era that produced them. But to deny the hurtful and derogatory nature of the images in Kelly’s early work, I believe, is also to deny his power as an artist. The images in these early issues of Animal Comics are ugly, but there is something in them that will not be ignored. In his mature work—read, for example, Ten Ever-Lovin’ Blue-Eyed Years with Pogo, or The Pogo Poop Book, or Kelly’s final collection, We Have Met the Enemy and He Is Us—Kelly breaks with these conventions. And the image he leaves behind is this one: P.T. Bridgeport, the circus bear, the character who was, in many ways, the real soul of Pogo, now old, tired, but more real and true as he stares at his beloved swamp and sees not a pristine wilderness but a wasteland of junk. But even here we find a possibility of hope and renewal:

Fig. 7 and Fig. 8: From the last two pages of the title story of Kelly’s We Have Met the Enemy and He Is Us (1972) (pages 41-42)

I started this post with a quotation from Walter Benjamin (translated into English by Harry Zohn) not for you but for me, as a way to remind myself of the value of interrogating images like the one of Pogo and Bumbazine sharing the slice of watermelon. If we fail to recognize images from the past as part of our “own concerns,” Benjamin argues, we run the risk of losing them, and their meaning, entirely. But here again I have left something out. Benjamin adds this final parenthetical statement to his fifth thesis: “(The good tidings which the historian of the past brings with throbbing heart may be lost in a void the very moment he opens his mouth.)”

So, a paradox: we must look carefully, search for these “flashes,” but we also risk negating them and their meaning when we speak or write about them. But to remain in watchful silence offers no real alternative. We must speak of these things, although, as we do so, we are not speaking about the past, not really. We are instead addressing the pain of what it is to live here, now, with each other and with these discourses that continue to blind and disorient us.

Fig. 9: Two gifts.

References

Andrae, Thomas. “Pogo and the American South” in Walt Kelly, Walt Kelly’s Pogo: The Complete Dell Comics Volume 1. Neshannock: Hermes Press, 2014. Print.

Andrae, Thomas and Carsten Laqua. Walt Kelly: The Life and Art of the Creator of Pogo. Neshannock: Hermes Press, 2012. Print.

Benjamin, Walter. Illuminations. Trans. Harry Zohn. New York: Shocken Books, 1968. Print.

Boym, Svetlana. The Future of Nostalgia. New York: Basic Books, 2001. Print.

Curtis, Betsy. “Nibble, a Walt Kelly Mouse” in The Golden Age of Comics. No. 1 (December 1982). 30-70. Print.

Fiore, R. “Sometimes a Watermelon Is Just a Watermelon.” The Comics Journal. April 3, 2014. Web Link.

Jarvis, Eric. “The Comic Strip Pogo and the Issue of Race.” Studies in American Culture. XXI:2 (1998): 85-94. Print.

Kelly, Walt. The Pogo Poop Book. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1966. Print.

Kelly, Walt. Ten Ever-Lovin’ Blue-Eyed Years with Pogo. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1959. Print.

—. “1920’s.” Five Boyhoods. Ed. Martin Levin. New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1962. 79-116. Print.

Pehanick, Andrew. Bridgeport 1900-1960. Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2009. Print.

Soper, Kerry D. We Go Pogo: Walt Kelly, Politics, and American Satire. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2012. Print.

Thanks to Mary Witkowski and Robert Jefferies at the Bridgeport History Center for their assistance in locating materials included here from the Center’s Walt Kelly clipping file. Also, I talk a little more about the Walt Kelly panel a November’s OSU conference here.

Brian: since I still can’t convince you to join Facebook (!) here’s a comment that I made on a link to your post: For a long time well-intentioned comics historians chose not to publicly address racist, sexist, and other troubling images in older comics by beloved cartoonists, or cautioned that critics were simply not equipped (and shouldn’t even try) to evaluate the social/cultural implications of artwork created decades ago. I *love* reading Brian’s rationale for why this approach won’t work anymore (and never did). I think this post and Noah?’s post from Monday have long-term implications for a lot of us who read/study this work, and so I’m glad to see the conversation continue. (Especially as someone who teaches this material in a state where the form and content of comics books are being regularly derided in the state legislature. Again.)

I think the remarks that you – as well as Jeet in his columns, and many others in the comments – frequently make in response to the complaint that these cartoonists were “of their time” and “that’s the way everybody did it” are very helpful in offering a solid counter-narrative to advance a conversation we can’t seem to stop having.

The “of their time” argument is made everywhere, not just comics; I talked about that over at the Atlantic a little bit back.

I think it’s especially entrenched in comics though. The defensiveness about comics as art and the fact that so many canonical works are from a time when pop culture was particularly noxious on these issues, combined with the resentment/demonization of Werthem’s social critique are I’d guess all reasons for that.

Excellent piece. I’d add 1) Kelly’s use of anthropomorphism is part and parcel of the linkage between nostalgia and the racial thematics in Pogo. There is an important thread linking funny animals to racial allegories that runs from Br’er Rabbit to Krazy Kat to Disney to Pogo. In some ways, funny animals are the default way of talking about race without talking about race. 2) The south as an imaginary home is worth thinking about as a specific outgrowth of the eruption of interest in regional cultures in the 1920s/1930s — everything from Faulkner to L’il Abner. 3) Jules Feiffer once made a passing remark to me that was interesting — that while Dogpatch in L’il Abner could be seen as a disguised Jewish village, a shtetl, an even stronger argument could be mad for the swamp in Pogo (despite Kelly, of course, not being Jewish). So there’s a sense in which the imaginary home as an archetype has greater resonance than just region. 4) Part of the ambiguity of all this is that as Kelly and other cartoonists became more sensitive to racial stereotypes, they stopped using black characters all together (or had black characters in funny animal form). There was a kind of ethnic cleansing of the comics in the 1940s (and comics have never returned to the strong sense of America as an ethnically diverse country that they had, in however problematic a form, in the early 20th century). 5). The impact of Krazy Kat on Kelly is worth thinking about — in some ways Herriman was the pioneer and master of creating anthropomorphic imaginary homes (Coconino county — a real place of course, but reimagined by Herriman) to allegorize race.

Pingback: Kibbles ‘n’ Bits 4/10/14: Check out the SCHMUCK Kickstarter! — The Beat

Pingback: Kibbles ‘n’ Bits 4/10/14: Check out the SCHMUCK Kickstarter! | ComicBookRAW

Thanks for the comments Qiana, Noah, and Jeet!

This week over email Qiana and I have been talking about our shared affection for novelist Charles Johnson, and as I was reading over these comments I thought again about his introduction to Fredrik Stromberg’s book Black Images in the Comics. It’s an essay worth considering as we talk about how we now read and understand these caricatures and stock characters. At one point on page 8 Johnson argues that

“These were products (as unreal as the ubiquitous imagery for today’s Roswell aliens, the ‘Grays’) that included supposedly black characters but were composed by and for whites, and if these images can serve us at all in the twenty-first century, they are only useful as the transcript of a pre-World War II, WASP imagination completely unmoored from reality.”

Johnson’s comparison of these racial caricatures to dream figures like the Grays brings us back to issues of the South itself and what Leigh Anne Duck, drawing on Edward Said’s phrase from Orientalism, refers to as the “imagined geography” of the U.S. South, especially as it was figured in the 1930s and 1940s (see Duck’s The Nation’s Region: Southern Modernism, Segregation, and U.S. Nationalism p. 2 and Orientalism p. 55).

Actually, Qiana, I wonder if this link between race and imagined geography is partly what Johnson himself is exploring in Middle Passage, especially when he introduces us to the Allmuseri and their god?

I’m also fascinated by Jeet’s idea of “funny animals” as the “default way of talking about race without talking about race,” that use of fables to explore deeper social issues. I’ve stumbled across those issues in my research on Captain Marvel for my book. Once Fawcett does away with Steamboat, Binder and Beck replace him with Mr. Tawny and, not long after, they begin exploring issues of race and class not only in a more progressive way, but also in a more allegorical fashion for slightly older, post-WW2 readers (I find it interesting that recently when I interviewed a science fiction writer who grew up reading Captain Marvel when he was a child in the 1940s, he dismissed the Tawny stories as the “worst” of the series, and insisted that I take a look instead more closely at the Monster Society of Evil serial). John G. Pierce has a short essay in the Fawcett Companion that touches on some of these issues of race and allegory in the Tawny stories.

Jeet also elaborated in more detail on his points in this Twitter essay yesterday: https://twitter.com/HeerJeet/status/453930265048408064

I should add that as I was thinking about Robert’s review, and as I was writing this essay, I had in mind something Jeet mentioned last year in his interview with Tom at the Comics Reporter (from the section on the Francoise Mouly book): “Strange to say, when I work on a biographical essay, I’m also often writing a type of disguised autobiography.”

Read the whole interview here: http://www.comicsreporter.com/index.php/cr_sunday_interview_jeet_heer1/

I’ve had this point in mind since I read the interview, but it struck me again when I was trying to answer the question as to why I’d written about Kelly in the first place—not to feel superior to him in any way, I hope, or in order to suggest that my racial attitudes are more advanced than his 1940s attitudes were, but as a way of interrogating my beliefs and the way they were shaped by the myths, the tensions, the fears, and the prejudices of Southern New England in the 20th century. So I think this point about criticism or biography as “disguised autobiography” is another way we might understand our practice as writers as we address these issues.

I really enjoy the tone of this piece, and though Brian has steered the conversations away from the more outrageous elements of the Fiore piece, I think the argument that Pogo’s rural swamp stories are actually based on his own New England experiences is a better defense of the minstrel elements inherent in this kind of dialect comedy than Fiore’s outright denials of minstrelsy. As one of the cornerstones of American comedy, the minstrel show was practiced by so many influential white and black comics and actors that it’s usually a mistake to dismiss something outright because of minstrel roots and references, which makes Fiore’s defensiveness misplaced. He is right that Bumbazine is a sympathetic character who is not a simple stereotype, but the character is Christopher Robin-esque in addition to being a part of a tradition that is racist at its foundation (it involves dehumanizing a race), but which often went beyond that foundation by introducing subversive, humanistic, and contradictory elements. Yes, there were vicious, hateful watermelon stealing and eating orgies (including some surviving early films), and Bumbazine’s pleasant enjoyment of a watermelon is unlike these. But that doesn’t divorce it from its incredibly obvious reference to a very common stereotype. One reason I did not comment last week was because so intelligent commenters already shared similar thoughts, most more eloquently that I could. So I am just sharing these comments (many culled from my research for Darkest America, a study of black minstrel performers I wrote with Yuval Taylor) as an excuse to praise Cremins’ engaging Kelly essay.

Hey Jake! Great to have you stop by.

As I think Jeet said, minstrel elements also seem to be central to Krazy Kat, and really to a great deal of early comic strips. It seems much more productive to do what you and Yuval do in your book, and try to see what those traditions mean or have meant, rather than as you say trying to deny that that tradition is being utilized.

I’ve been writing about racial caricature for many years. My main thesis has always been that they have much to teach us about racial attitudes in the United States. The first, “The Misapprehension of the Coon Image,” propose a categorization of the basic types of racial caricature: the Sentimental, the Sentimental/Condescending, the Condescending, and the Vicious. A subsequent article, “Affectionate, Sympathetic, and Completely Racist,” examined the black servant characters in Gasoline Alley, and how an artist with all the will in the world and the best intentions in the world would nevertheless propound a fundamentally racist view. A short article entitled “Blackface and Gayface” considered the similarities and differences between stereotypes of African Americans and gay people, and the equivocal position of the people who informed them. Based on these many years of thinking I hope fairly deeply on the subject, I compared the imagery employed by Kelly and how it differed from the standard stereotypes of the time, and while allowing that they could be interpreted as derogatory, and concluded that Kelly had made his best efforts to go against the tide of his time and had done creditable work. But then, I don’t see why I should be given any more credit for good faith than you’d give Kelly.

One thing I do wonder is, why is it that Christopher Robin can interact with animals without being degraded and Bumbazine cannot? The only differences I can see are race and nationality.

There is one and only one way to make amends for racism, and that’s the one put forward by Dr. Martin Luther King: To achieve a material equality sooner rather than later. Let me tell you something about that. About 25 years ago I started to do secretarial work, and one thing immediately was that there was a point in the hierarchy where you just stopped seeing black or brown faces. I mean, one or two maybe, and usually none. In 25 years this hasn’t changed the least little bit. As far as the upper levels of the professions what you have is not a glass ceiling but a glass floor. What I interpret this to mean is that addressing what you might call top line racism, the racism of public attitudes, does relatively little to effect the infrastructure of inequality. The main purpose these operatic denunciations of the racism of former days serves is self-exculpation. It is the false theory that condemnation is expiation.

R. – I think it is interesting and worthwhile to point out how Kelly’s references to stereotypes differed from uglier ones at the time, I just feel the tone of your piece went too far, divorcing it from a problematic tradition. Thats aid, I actually ended up writing short, general readership reviews of some of the other books that you surveyed in the same column, and appreciated what you had to say about the Wunder and Carlson books (the Trib had already reviewed a Kelly book in 2013 so chose not to run that one), so I overall enjoyed that column, I was just genuinely surprised with how adamantly you defended the watermelon scene and how you removed the townsfolk from traditions of racist stereotypes (which was not a necessary act to defend the book, I let me child read it, but explained the context of the stereotypes). In fact, when I read Andrae’s introduction I felt he was going too easy on Kelly, which is where I thought you were going to go with your critique.

“There is one and only one way to make amends for racism, and that’s the one put forward by Dr. Martin Luther King: To achieve a material equality sooner rather than later. Let me tell you something about that.”

I think this is a basic confusion. No one in this discussion believes that we’re making “amends” for racism by pointing out racist stereotypes in Walt Kelly’s work. Nor has there been a single “operatic denunciation” that I’ve seen — or really any particular denunciation at all. Refusing to acknowledge problematic elements in his work is a problem, though, because it’s deceptive about the work, and leaves us with a worse understanding of it, and because acknowledging the ways racism works in the past is part of dealing with racism in the present. So it’s not about making amends, but about trying to be honest about racism past and racism present.

I’d also point out that in your language of “amends”, you’re again ignoring the possibility that some of the people in the conversation might be black. Those folks aren’t looking to make amends; they’re asking you not to pretend racism didn’t happen or isn’t present just because you want to put Kelly beyond censure. And, again, you can criticize Kelly and suggest there were problems with his work without saying that he’s an evil person, or that his work needs to be condemned. You can even do so while thinking his work is great, as I believe Brian does. But I do think it’s worth thinking about the extent to which your analysis of what’s wrong with criticizing Kelly seems to erase black people’s voices in a manner similar to the way in which you want to erase Kelly’s use of blackface iconography. I think the two are connected.

I don’t agree with the idea that eradicating material inequality is, in and of itself, a project privileged over all other projects having to do with the remediation of our racist history. It’s necessary, but not sufficient.

Unless you’re advocating “culturally separate but materially equal”, you have to address the cultural piece, and that means not just facilitating space and opportunity for the voices and perspectives and experiences of people of color to be expressed where white people can hear them, but also ensuring that your ears are entirely open to hearing them.

Recognition of the complexity of our racist past is an important part of that openness, but nostalgia for or uncritical appreciation of that past is not. Once you’re really heard those voices, you can’t unhear them – even your recognition of historical context will be informed by having heard.

That transformation of hearing is I think critical to addressing racism period – whether “making amends” or any other aspect.

That’s a great point, Caro. Racism isn’t just material; it’s an act of aggressive imagination. The imaginative and material aspects are really intertwined, too, in such a way that they’re hard to separate in any number of ways.

Nice phrase: “an act of aggressive imagination.” Or maybe “an aggressive act of failed imagination.”

I think black people are perfectly capable of speaking for themselves and would not presume to speak for them. Unlike some other people I could name. I give a chapter and verse description of what the prevailing stereotypes were and why I thought Kelly’s stories didn’t reflect them, and you say I’m pretending racism didn’t happen. I do not expect justice from this court.

Re Jake Austen, I suppose it’s what I get for being antagonistic. The Devil drives till the hearse arrives. If I gave you the impression I was divorcing it from the tradition when I thought I was placing it in the context of that tradition and explaining how it differs, I guess that’s on me.

I suspect the problem may be with the idea of something being demonstrably “not racist.” The way that many “post-racist” white people display their genuinely naive ignorance of ongoing forms of casual racism is with the simple declarative disclaimer, “But I’m not racist.” If Walt Kelly borrowed elements of the racist culture around him, while evincing a progressive worldview overall, that doesn’t make him a monster, it just doesn’t make his art utterly and thoroughly “not racist.”

“I think black people are perfectly capable of speaking for themselves and would not presume to speak for them. Unlike some other people I could name.”

Yep, right on cue.

I’m not speaking for black people. I’m telling you that, as a reader, when you say that the problem with your interlocutors is that they are looking for absolution, that strongly suggests that you believe all of your interlocutors are white (unless you’re claiming black people need absolution, which would be odd.) But all of your interlocutors and readers are really not white. Dealing with this is probably something you should think about.

Edited to remove excessive snark. Sorry about that.

“But all of your interlocutors and readers are really not white”

I’m assuming you chose your words wisely (or snarkily), as Mr. Interlocutor, the straight man in a traditional minstrel show, is usually a non-blackface character, in both white-cast and black-cast minstrel shows.

Hah! No, I’d forgotten about Mr. Interlocutor; the choice of words was serendipitous (or not, depending on how you look at it.)

A slight correction: Mr. Interlocutor was traditionally in blackface as well, although he affected a high-toned way of speaking and acting. According to Eric Lott and others, the idea of the interlocutor being white was mostly mistaken.

And regarding Bert’s idea about Kelly “borrow[ing] elements of the racist culture around him, while evincing a progressive worldview overall,” one could propose another option — that Kelly was trying to use those elements as part of his progressive project.

This is often the case made for Mark Twain, Huck, and Jim. Here too, we have a character, skinned in stereotypes, but we also have the human being whom the young white boy — and his older white readers — sometimes can and more often cannot see. And the stereotype is part of that depiction and that project, not just an misstep. Morrison called this “the ill-made clown suit that cannot hide the man within.”

I am not willing to argue that Kelly is doing any such thing here: that final watermelon panel may be nothing more than artistic laziness. But I think that Fiore might be saying that unless one thinks that the rest of the story — and Kelly’s surrounding work — is equally lazy, why not consider the possibility that he is trying to “do” something progressive or counter-intuitive with this last-second stereotype here?

Whether this gambit is successful is another matter. But here, as always, intention counts.

Thanks for the kind comments, Jake. And thanks to everyone else for chiming in. I was travelling this weekend and didn’t have the chance to follow this conversation closely.

Robert, was your essay “Blackface and Gayface” in TCJ? Do you remember the issue number? I’d be interested to read it. I have my digital subscription so I should be able to access it if it’s been scanned.

Also, if you haven’t seen it, I thought you’d be interested in the minstrel sequence in Oscar Micheaux’s Ten Minutes to Live, one of his early sound films from 1932. It appears early in the film:

https://archive.org/details/TenMinutestoLive

It’s a very curious performance, as it appears that it both records a minstrel performance one might have seen in a Harlem nightclub while at the same time critiquing or deconstructing it. Mel Watkins goes into some detail on the scene in his book African American Humor. I thought of the Micheaux sequence after reading your post at TCJ on the minstrel section from Babes in Arms.