My copy of Joel Christian Gill’s new graphic novel arrived in the mail last week shortly after I read Frank Bramlett’s post on the way editorial comics depict Michael Sam, the openly gay, black football player who was recently drafted by the NFL’s St. Louis Rams. Of particular interest to Frank was how few of the comics he found rely on metaphor to convey meaning and instead invoke more literal representations of Sam to comment upon the significance (or insignificance) of his social identity. As the post makes clear, scrutinizing the visual and verbal shorthand that comics use to illustrate abstract ideas like race or sexual orientation can reveal a great deal about how society negotiates changing attitudes, institutions, and avenues of power.

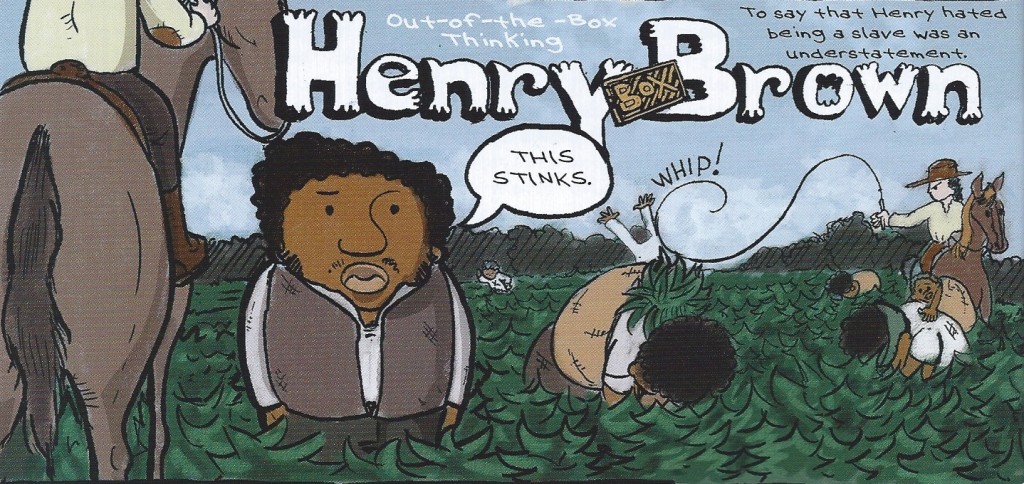

Gill’s collection, Strange Fruit: Uncelebrated Narrative from Black History, provides us with another opportunity to raise questions about the figurative modes of expression that today’s comics creators use to represent race and racism. Readers of the short stories in Strange Fruit quickly learn to appreciate the playful succinctness of Gill’s iconographic language. He knows when to use humor and sight gags to advance the story. (On the experience of enslavement, Henry “Box” Brown remarks: “This stinks.”) But Gill knows when more serious cultural cues are needed too, as in the two-page spread where Brown’s body, shown curled inside a wooden box, silently tumbles from slavery to freedom.

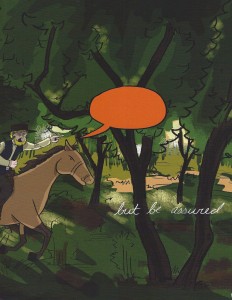

Yet in the graphic novel’s accounts of lesser known African American figures and infamous historical events, Gill’s depiction of race hatred also caught my attention. When angry whites confront African Americans in these stories, their speech is represented as orange or red word balloons that contain no printed text. It isn’t difficult to imagine what is being said in these exchanges. But perhaps that is the point.

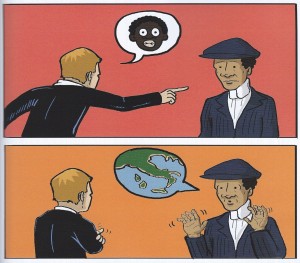

In other instances, the verbal threats and insults of whites are condensed into a single image of a black caricatured face with wide saucer eyes and swollen lips. The panel below is from a stunning story called “The Shame” about the denigration and forcible eviction of the black residents from Malaga Island off the coast of Maine in 1912. In the exchange, a former Malaga resident is attempting to “pass” and conceal his black identity.

Exactly what is being said here? Can the sentiments expressed in the top panel alone ever fully be translated into printed text? Gill’s arrangement of the well-known visual racial caricature seems to go beyond words to convey a culturally and historically situated discursive practice. The pictographic balloon draws our attention to the constructedness of an image meant to articulate a host of ideas about black inferiority. (The accused responds with a fiction of his own by attributing his physical features to an Italian lineage.) I also think it’s fitting that this exchange appears in a story that takes place during the early 20th century when caricatures dominated visual representations of blacks and other ethnic groups. In his efforts to retrieve the neglected history of African Americans, Gill arguably makes those early cartoonists complicit in his critique of racism as well.

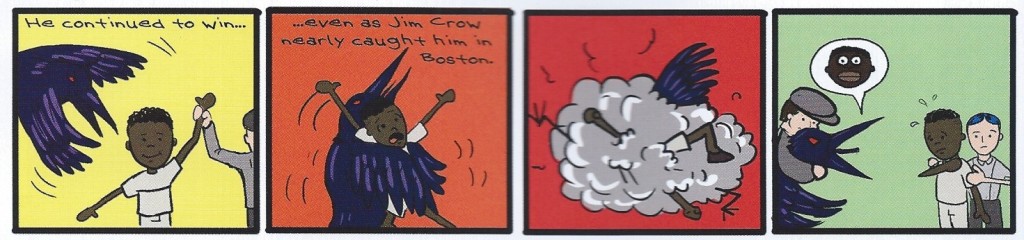

Strange Fruit goes a step further in completely depersonalizing white supremacist ideology by representing angry white people literally as (jim) crows. In stories like “The Noyes Academy” about the destruction of the nation’s first integrated school or “The Black Cyclone” about one of the fastest black cyclists in the world, outraged whites are transformed into belligerent red-eyed birds that chase and poke their wings into black faces. They speak only in blank word balloons, pictograms, and the occasional “caw!”

Relying on these kinds of visual metaphors is not without risk, but I believe that Gill’s comic succeeds in redirecting the reader’s attention to the voices that matter most to him, that of Henry “Box” Brown, Harry “Bucky” Lew, Richard Potter, Theophilus Thompson, Alexander Crummell, Marshall “Major” Taylor, Spottswood Rice, and Bass Reeves — men who despite their different circumstances, encountered racism’s vitriolic squawk in comparable ways. Black resistance and agency remain key elements in every incident chronicled in Strange Fruit, even for the stories that end in tragedy (these are the uncelebrated, after all). Let’s hope we’ll see more narratives of uncelebrated black women in volume two.

Last month, World War Z writer Max Brooks and artist Caanan White published, The Harlem Hellfighters, a graphic novel about an all-black infantry unit during World War I. It shares with Strange Fruit an interest in recovering details about African American life and culture that have been overlooked (and both are helpfully endorsed by Henry Louis Gates, Jr.). But in contrast to the more conventional heroic narrative and mimetic style of The Harlem Hellfighters, I think that Gill’s experimental choices result in stories that are not just aesthetically richer, but that also illustrate a wider range of interpretive possibilities for remembering the past.

The way in which Gill represents racist speech in Strange Fruit is just one example of these artistic choices. What do you think about his strategy? I’d be interested to hear if you’ve seen similar approaches in other comics too.

I just saw Gill’s work at the bookstore this week so now I’ll need to pick up a copy. Thanks for this overview of the book, Qiana!

Marnie Galloway uses a similar technique in the speech balloons of her series In the Sound and Seas. You can read portions of Volume 1 on her website, and Vol. 2 should be out later this year:

http://monkeyropepress.com/in-the-sounds-and-seas-volume-i/

In Galloway’s narrative, images in the word balloons–or the absence of images–suggest expression that is beyond language, either the mystical utterances of the three woman who speak creation into being in the first few pages, or the interactions between the two characters later in Vol. 1.

Just as Gill confronts issues of race while also recovering neglected or forgotten stories from African American history, I think Galloway is addressing the role of women in narratives like The Odyssey. She even includes a passage from Pope’s translation to introduce this first volume. I read her work as existing in the same tradition as Sappho and H.D.’s re-readings and revisions of the Homeric myths, for instance.

So I wonder if Galloway and Gill are working in the same fashion, trying to deconstruct racist and patriarchal speech by reducing those utterances to images, or suggesting a kind of absence at the heart of that speech, a void waiting to be filled with sense.

I’m looking forward to reading more of Gill’s work!

It’s interesting to think about in comparison to Tarantino’s Django a little, and the controversy around racist speech there. Seems like a way to get around the problem of recording or acknowledging racial slurs without necessarily reproducing them (though there’s some reproduction of blackface iconography in the word bubbles, I guess….?)

You are all correct in some ways. I read something Chris Ware said about how he wants his comics to read like hieroglyph. What I think he wanted the reader to see was the entire understanding of that image’s meaning imbedded in it’s visual impression. The colors are supposed to be abstract representation of mounting rage. The black faced symbol (in my drawings that image is called “racsim”) is supposed to have the embedded cultural meaning. I used the crows for 2 reasons. 1 they are fun to draw, and two I wanted a metaphor like that of old Tim Johnson from to kill a mockingbird. Qiana is right. I wanted to take the humanity out of the racist. BTW Volume 2 will have more women.

Pingback: Strange Fruit Review | joelchristiangill

Brian, thank you for including the link to Marnie Galloway’s work. Wow, there is so much rich material to enjoy and decode there. It’s interesting how the absence of words and use of pictographic language feels very contemplative – at least in the sample pages – whereas the blank word balloons in Gill’s comic are loud, screeching intrusions. This is a nice juxtaposition.

Noah, yeah, just on a practical level (though it’s an ideological choice too), Gill is sidestepping that problem of having to reproduce racial slurs. It also made me think about Baker’s decision not to use words in Nat Turner.

Joel, hey! Thanks for stopping by and checking out the post. I appreciate you sharing this information about your process. If you’re willing and able to share a bit more – to Noah’s suggestion, I’d be curious to hear whether or not the idea of reproducing racial slurs was an issue for you or your editors at all in the design? But I’m mostly intrigued by this idea of “taking the humanity out of the racist” because that seems like it can be really tricky. Were you concerned at all that generalizing racist speech would take away from the depiction of the specific nature of the bigotry these black men faced?

Of course, not even all visual abstractions are abstract in the same way. It would be pretty awesome to compare the racist “Jim Crows” in Strange Fruit to the ones Jeremy Love illustrates in Bayou…. more material for that article on race and anthropomorphic animals that I’m determined to write one day!

Using the language was not an issue. I wanted a more interesting way to use the language, without beating people over the head with racial slurs. If you have seen Django (at this point who hasn’t?) then you know how “nigger” is used so much that it becomes wallpaper. I want the words deeds and actions to always bring to mind the completeUsing to Kill A Mockingbird reference again, I think that people become inhuman when they are overcome by racism. There are plenty of people in the world that have become “human” after an encounter with someone or something that humanized them. Like the Town that Scout grew up in the book became inhuman when confronted with race, I wanted to convey the same kind of inhumanity.

Appreciate you taking the time to share some insight into your thinking behind the book, Joel! I’m already looking forward to book two.