In the heart of the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence is the Salone dei Cinquecento (Hall of the 500), which, as the name implies, was designed to seat the 500 members of the Grand Council. In the 1560s, Giorgio Vasari was commissioned to create a series of frescoes on the walls and oil paintings on the ceiling of this hall.

West Frescoes in Salone dei Cinquecento by Vasari

(Photo by Ron Roznick)

The frescoes depict battles and military victories by Florence over Pisa and Siena (in chronological order, no less). These are massive pieces of art that are designed to impress visitors to the Hall, which functioned as the court of the Medicis. It is interesting that they are presented side by side with what look like extremely ornate panel borders. They are too large for the arrangement to be accidental, which means that Vasari (or his patrons) wanted these pieces to be close enough to create an effect larger than the sum of the parts.

It would be possible for a viewer to spend hours examining every detail in each fresco, but it is clear that the intended effect of the presentation is to impress visitors to the hall with both the military prowess and wealth of the city with the visual immediacy of how it has been successful in the past (and, by implication, could be in the future). It may only be because I read comics that this presentation reads as a three panel strip where the middle panel is less important than the two on the ends.

A portion of the ceiling of the Salone dei Cinquecento by Vasari

(Photo by Ron Roznick)

The 39 oil paintings on the ceiling of the same hall represent great episodes from the life of Cosimo I and scenes from the history of Florence. The presentation of these paintings in a massive, ornate grid reminds this modern viewer (and reader of comics) of the carefully arranged panel grids of a comics page – especially since each of the paintings has its own descriptive caption. And there is even an implied order that these are meant to be viewed in; the circular painting in the center, for example, is The Apotheosis of Cosimo I de’ Medici which depicts his coronation by the personification of Florence.

Again, the intended effect is to produce awe at a government that had enough disposable income to commission such a piece. Keeping in mind that thirty feet of open space separates the ceiling and the viewer, the narrative aspect of the arrangement is less obvious on an initial viewing and only becomes evident with time to study the detail. But it is there.

(Better views of these pieces can be found at this site.)

These artworks take advantage of the basic artistic process that enables comics – the implied narrative- sequential connection that comes from placing two pieces of artwork near each other, regardless of whether those pieces are related or not.

The Salone dei Cinquecento is a good example of a narrative-sequential artwork outside of the comics tradition because it contains two distinct examples with very different approaches from the same creative team. It is easy to avoid referring to either work as “comics” because “comics” was not part of the artistic idiom at the time of creation. There are other examples, of course – narrative-sequential artwork is everywhere if you have a broad enough perspective.

And, to be honest, finding examples of narrative-sequential art from before the advent of comics-as-comics is almost too easy. What I find especially interesting are the 20th Century examples of non-comics narrative-sequential art, mostly because they arise outside of an explicitly comic-making tradition but are still contemporaneous with what we think of as modern comics.

Wassily Kandinsky, “Thirty” (1937)

Kandinsky was living in Paris when he made Thirty, which means that he would have been aware of bandes desinees (BD) as a general cultural phenomenon. It is possible that he might have encountered it earlier in his travels around Europe, but it would have been impossible to miss it in Paris in the 30s. If he had wanted to make comics, there was ample opportunity for him to do so. He didn’t, but this was as close as he got.

Despite the fact that it is an explicitly abstract piece, Thirty still takes advantage of the implied relational connection that comes with arranging discrete pieces so close together. It is an extremely successful grid and provides an overt narrative framework for the viewer to build an interpretation around. If anything, this grid is closer to the effect generated by the ceiling of the Salone in Florence. It emphasizes the overall effect first and rewards subsequent scrutiny.

Lynd Ward Wild Pilgrimage (1932)

There is little evidence that Ward was thinking in terms of comics when he produced his woodcut novels like Wild Pilgrimage. Comics were certainly around at the time, but they were largely regulated to the newspapers and comic books were still in their infancy.

Each page of Ward’s novel only has a single image and there are no captions, so these are comics-like at best. But these absolutely take advantage of the fact that images presented in sequence can be used to tell a story. As allegorical tales, Ward’s novels were tied to the worker’s movements of the times – a very different audience and purpose than American comics of the period.

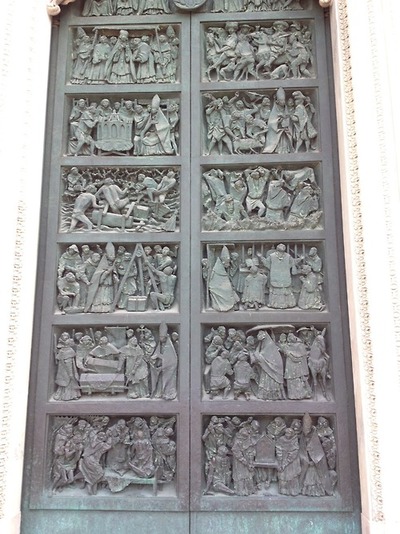

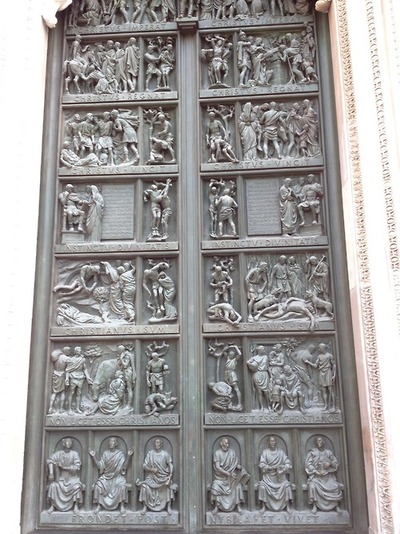

Doors of the Milan Duomo (mid 20th Century)

Because I have taken Frank Santoro’s composition course, these doors remind me of the fixed grids that he teaches in his class. It absolutely makes sense that an artist attempting to produce a narrative in bronze would divide the available space into rectangles of equal size. It is a natural impulse and an obvious design solution. I have no idea who designed these doors or whether that person had a comics background. I’m happy to get more information if someone has it.

Max Ernst, “Une Semaine de Bonte” (1934)

Like Kandinsky, Ernst was living in Paris when he worked on Une Semaine de Bonte, although he actually completed it in Milan. Like Kandinsky, Ernst would have been aware of the BD culture of the time – even if it was only a cursory cognizance.

Like Ward, Ernst’s novel takes advantage of the narrative aspects of art presented in sequential order to tell a story. Like Ward’s work, each page contains a single image and, unlike Ward’s work, these pages have captions more often than not. Despite the fact that they are contemporaries, there are very few other similarities between Ward and Ernst beyond the fact that they both arrived at the same solution (images in sequence) for the same purpose (to tell a story) from very different (non-comics) directions.

It’s tempting to categorize these kinds of explicitly narrative-sequential art as comics that don’t know that they’re comics. I think it’s safer to say that the idea of presenting artwork in sequence for narrative purpose is such an easy conceptual leap that it should not surprise anyone that it shows up so often in so many disparate places; diptychs, triptychs and other polyptychs have been acknowledged art formats in multiple cultures for centuries, if not longer.

Comics, specifically, are a refinement of the concept for a very specific purpose and medium. Rather than trying to shoehorn everything into the comics tradition because that’s the most obvious context for modern viewers, it would make more sense to think of it the other way around – comics are no more and no less than a distinct subset of the larger grouping of narrative art in sequence.

Having said that, it would not be a bad idea for contemporary comics creators to pay attention to these other examples of how past artists have used this technique to good effect. This is no different from telling creators to study how other artists have used color theory, figure drawing or one point perspective.

Interesting article, personally I agree; classifying all art in sequence as comics gets out of hand, you have to consider comics in terms of their cultural context rather than just content.

I find all the stuff that just boarders between cartooning traditions and more traditionally “fine art” practices really interesting, it’s an odd distinction. Just to throw it into the mix, there’s a really good set of Picasso cartoons here

here http://www.cartoonbrew.com/illustration/picasso-the-cartoonist-24389.html

These two especially feel like comics to me,

http://www.cartoonbrew.com/illustration/picasso-the-cartoonist-24389.html

they put me in mind of a lot of the Zap comics, or perhaps a more violent Herriman.

I think genre distinctions are often fairly arbitrary and fuzzy, but I do like the idea of thinking of comics as one aspect of a tradition of narrative art. Would that tradition encompass film a well, I wonder? Or animation? Seems like it could…

What’s really interesting to me is that the Picasso cartoons are from about the same time period as three of the four examples from the 20th Century that I presented. We know that Picasso read comics, though – one of his favorite strips was Krazy Kat.

The Picasso-loves-Krazy story, I’m sorry to say, has no evidence behind it, according to Herriman biographer Michael Tisserand.

But there is evidence for a Marston-loves-Krazy story, however, so at least Noah is heppy.

Gertrude Stein reported that she had to save her copies of the Paris Herald-Tribune so Picasso could read the funnies. I believe it was the Katzenjammer Kids she mentioned. The Herald wasn’t a Hearst paper, so it’s doubtful it would run Krazy Kat.

Always good to be reminded of Vasari’s painting; he’s remembered mostly as the first great historian of art.

Great article, lovely art … why not make things even more simple and just call all comix: telling-stories-with-pictures.

Suddenly, Raphael, the sculptors of the Ara Pacis and the painters of Akbar’s ateliers are part of the mix. And frankly, you’ll learn a heck of a lot more about telling stories with great art from them than you ever will from Jack Kirby.

That should make the kiddies spit up their Soylent Green …

Great point, mahendra. For decades, comic fans have attempted to trace a fine-art lineage to their medium, assuming (if only implicitly) that the esteem of such associations will rub off on comics’ own practitioners. It may work in the opposite way.

If we truly start to see comics as simply one small branch of narrative visual arts — or as part of what Domingos called the “expanded field” — the “greats” in the field may start to diminish in comparison, making us wonder why cartoonists have done so little with so much.

The problem with having too broad a definition for comics, for me at least, is that it basically ignores the fact that comics have had a tradition outside of the fine art world. People should absolutely think about how comics relate to narrative art in general and bring it into their work, and people have done, but to call all narrative art comics kind of makes the word meaningless.

The more meaningless we make these idiotic labels, the sooner we can get back to doing good work.

And Peter’s right: why do most cartoonists do so little when so much is available for study? When you look at crap, you’ll wind up drawing crap.

I better take my medication now …

Mahendra you’re being reductive; it does not become easier to create good work if you just ignore the context of where the art you look at came from, how it was viewed in its time, and how the creator thought about it, you just end up with uninformed people who don’t know how to interpret work. You can have an open art form without ignoring that their is specific history to it.

Also, yes, if you expand the a field from around 150 years to the full scope of human history, then the handful people working in a specific form of storytelling and drawing in that last 150 years do seem a lot less important.

/rant

For practical purposes, the history of an artwork is usually immaterial … what is really important is training artists (and critics) to use their eyes. Just look, what more do you need? as Kandinsky once exhorted artists.

It take practice to look well. So why not look at the best and thus speed up the process?

It’s not about the history of specific artworks, it’s about having perspective on the history of art in general, looking is important don’t get me wrong our visual literacy needs a lot of work. But I’m saying it can’t just be that, you also need to context which genre, period, etc allows.

Your argument also means we have to figure out what is altogether “good art” and worth looking at, and presupposes that looking at said “good art” will improve our ability to look.

Pingback: Inspiruj?ce artyku?y #1 | Sztuka Komiksu