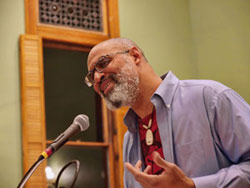

Tim Seibles cuts straight to the heart. When I met him at his hotel to walk him over to my wife’s poetry class, conversation leapt from “nice weather” to “parents with Alzheimer’s” in a single bound. He was giving a reading that night and—because his most recent book, Fast Animal, includes five poems about Blade the Vampire-Hunter—visiting my Superheroes class the next morning.

Seibles was in high school when Marvel launched the character in 1973. He’s not the first black superhero—Black Panther debuted in Fantastic Four in 1966 , the Falcon in Captain America in 1969, and Luke Cage in his own title in 1972—but he beat Brother Voodoo to newsstands by two months. The comic book market was slumping, so Marvel was desperately mixing its superhero formula with blaxploitation and horror. Shaft hit theaters in 1971, Super Fly and Blacula in 1972. Hammer Films had been pounding out low budget Dracula and Frankenstein flicks for over a decade, but the Comics Code prohibited “walking dead, torture, vampires and vampirism, ghouls, cannibalism, and werewolfism” until 1971, unless the horror was “handled in the classic tradition such as Frankenstein, Dracula, and other high caliber literary works.”

Marvel pounced with Werewolf by Night, Tomb of Dracula, The Monster of Frankenstein, and a half dozen other horror-tinged titles. He sounds like a pseudonym, but flesh-and-blood writer Marv Wolfman moved to Marvel at the same moment, and soon he and artist Gene Colan were adding a black “vampire killer” to their Dracula cast. I’ll let Seibles introduce him:

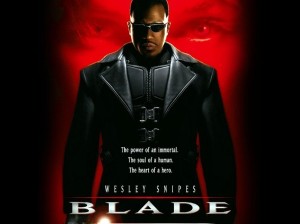

“Years ago, a pregnant woman was bitten by a vampire and turned. Her son was born with the thirst but, being half-human, he could walk in sunlight unharmed. Though vampires quietly dominate the world, he fights them—in part to prove his allegiance to humanity, in part to avenge his long isolation, being neither human, nor vampire. Because of his deadly expertise and weapon of choice, they call him: BLADE, THE DAYWALKER”

It’s hard not to read the character as a racial metaphor. Barack Obama turned thirteen when the Supreme Court ruled on Roe v. Wade that year, and though President Nixon made no public comment, White House tapes reveal his opposition to abortion, except when “necessary,” as “when you have a black and a white. Or a rape.” I read all vampires as rapists, so it follows the horror of our cultural logic that the first black half-vampire would have to take a vow of blood celibacy. Note all those unconscious blonde women draped in Dracula’s arms too. Blade’s skin makes explicit more than one coded fear.

Seibles told my class that he saw the character as an “emblem of alienation,” a metaphor for what it feels like to be black in the U.S., to feel “both American and not.” The night before they heard him read his poem “Allison Wolff,” set in 1972 when “Race was the elephant / sitting on everybody.” Seibles was born in 1955, the year Emmett Till was lynched, and that horror haunts the teenaged Tim the first time he kisses a white girl.

Fast Animal includes a high school photo of Seibles, “circa 1971,” long before he met Blade. The half-vampire lurked around Marvel’s black and white magazines for a few years, vanished for a decade or so, then reawakened in the 90s. I showed my class the 1998 film, which opens with Blade’s vampire-assaulted mother bleeding out on delivery room table. David S. Goyer penned the screenplay, which also explains Goyer’s rise to dominance in the DC film universe since both his Batman Begins and Man of Steel screenplays open with the bloody deaths of their heroes’ mothers. Seibles said the two sequels weren’t as good, and both the Spike TV and anime series were news to him.

Apparently Wesley Snipes spent 2010-2013 in prison for tax evasion. He last played Blade in 2004, about when Seibles started using the character in his poetry. Seibles said it was George Bush who turned him, that feeling of “a deep trouble taking over the country,” or, as his Blade explains: “it’s almost like I can’t / wake up, like I’m living // in a movie, a kind of dream: / action-packed thriller.” Political essayist Jonathan Schell drew the same conclusion in 2004. Since 9/11 and the War on Terror, it seemed to Schell “history was being authored by a third-rate writer” compelled “to follow the plot of a bad comic book,” with the President turning “himself into a sort of real life action figure.”

The vampires in Fast Animal do have a Wolfowitz-neocon vibe: “the ones / who look in the mirror / and find nothing // but innocence though they stand / in blood up to their knees.” But Seibles-Blade address a much larger audience, everyone watching “the war on TV” while not wanting “to see / what’s // really happening,” all of us living “in / the blood,” fighting for “The right to live / without memory,” to ignore “So many / centuries, so much / death.” Slavery, Seibles reminded my class, is a kind of vampirism too, one of many ways America has exploited the world. Of course Blade longs for “this country / before it was bitten,” even as he mourns: “I don’t know how // to save anybody from this.”

Seibles called Blade his “mask,” a perfect term for my Superhero class. He used Blade to channel his rage, he said, likening the character’s name to a pencil: “Some days // I think, with the singing / of my blade, I can fix / everything.” That’s a poet’s superpower, to reveal through language, since “evil thrives best in the dark.” He even gave us his mission statement: to fight “inattentive dumbassery.”

Seibles also has a pair of poems in the new anthology Drawn to Marvel: Poems from the Comic Books (where my wife, Lesley Wheeler, and I do too). Swapping his vampire superhero mask for Natasha and Boris of the Rocky and Bullwinkle cartoons, Seibles playfully critiques American capitalism, a theme one of my students asked him to expand on. Another asked how, if our leaders are as stupid as Seibles suggests, were they smart enough to come to power? But my favorite question came at the end of class: What would Blade do if there weren’t any more vampires to fight?

Superhero missions, like Batman’s quixotic “war on criminals,” guarantee never-ending battles. You never run out of bad guys. You never get to walk away. But instead of talking vampires, Seibles talked about his father. The idea of sitting in a room of white people and discussing race, his father couldn’t imagine such a thing. His father can’t believe there are white people who aren’t racists. Sure, at an intellectual level, of course he can, but the idea is meaningless at any emotional level.

I don’t know what year he was born, but let’s say circa 1930—a moment my class understands well in terms of American eugenics. We read excerpts of a standard high school biology textbook that explained the hierarchy of white supremacy and advocated the extermination of unfit gene pools. That’s not something you walk away from. That’s not a world that ever runs out of bad guys. Seibles described Blade’s life as a psychological and spiritual war—one his parents’ generation can never stop fighting.

The only hope, he said, is for Blade’s children.

Pingback: Blog fodder for June 7th through June 10th | Wis[s]e Words