A few months ago, Ross Campbell posted an update to his blog about his ongoing comic series, Wet Moon. After reassuring readers that he was making progress on the seventh installment, he shared the news that volume eight will likely be the last. “I’ll be calling it quits after that, at least for a while,” he writes. And though he hints at the possibility of some kind of spin-off, Campbell seems pretty clear about his need for creative breathing room away from Wet Moon, and perhaps even some closure. His remarks are what prompted my question this week: when and under what circumstances should a comic series end?

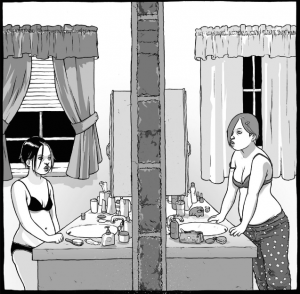

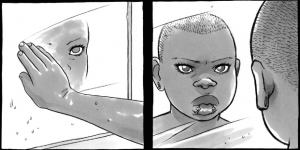

Oni Press first began publishing Campbell’s series in 2005, so as he mentions in his post, it’s been nearly a decade since Cleo, Trilby, Audrey, and Mara started their first year at the art school in their hometown of Wet Moon, somewhere in the Deep South. The comic’s young aspiring poets, playwrights, and illustrators are chain-smoking goths and metal heads, young vegan swamp things who hang out in coffee shops and indie video stores between classes. Not surprisingly, a sense of panic, self-questioning, and irrepressible curiosity underscores their transition from high school to college. Even more interesting, though, is how Campbell’s narrative and aesthetic style values intersectionality in ways that the characters themselves are still struggling to appreciate. In the generous curves and angles of their bodies, gender, race, sexuality, ability, and regional identities are alternatively extolled and effaced according to the shifting cultural attitudes and language of youth. Elements of horror and mystery add even more energy to comic’s coming-of-age drama.

Having just read the six volumes of Wet Moon on a weekend binge last year, Cleo and the other characters are new friends of mine. I’m still in the early swoon of fandom and quite satisfied to linger here a while before venturing into more scholarly analysis. But Campbell has lived with the story for ten years or more, and his discomfort with this fact can be instructive for those of us who study comics. His post concludes:

i don’t know if it’ll be career suicide to end Wet Moon, but it seems like the right thing to do. i love the characters but i’ve felt more and more crushed underneath all the storylines i’ve woven together, i feel like i’m paying for the decisions my 24-year-old self made, and i need to wipe the slate clean and move on. other reasons are i feel like i’m always trying to repurpose Wet Moon to fit with myself as i get older and change as a person, people change a lot in 10 years, and also that with each new book, WM gets more and more inaccessible, i don’t want it to become like long-running superhero comics or those Japanese comics that you’re interested in until you find out they’re 25 volumes long and counting. bleh.

Campbell’s concerns could easily apply to any form of storytelling with recurring characters, from Sherlock Holmes mysteries to daytime soaps or the prequels and sequels of Star Wars. Yet comics struggle with the pleasures and burdens of serialization in distinctive ways. The form’s most popular genres, such as the long-running superhero comics that Campbell references, are often bound to the creative decisions of the past and to the fans who want to keep it that way. As Danny Fingeroth explains, “We learn and grow – we change – from experience. For the most part, serialized fictional characters do not. This is at once a great strength and a terrific weakness for them.” Clearly the same can be said of their creators too.

Campbell cites the complex continuity in Wet Moon and the related issue of inaccessibility, along with his own personal growth as reasons to risk what could be “career suicide.” (Given his recent work on TMNT, the weekly updates to Shadoweyes, and everything else he’s done, I don’t see that happening.) But Wet Moon offers its own evidence of the rewards that can come with taking such a risk. Consider the way Cleo’s friend Mara slowly sheds her brooding intensity over the course of the series along with her nose rings, leather mini-skirts and black lipstick. “Just felt like it,” she says to Audrey in book 3, but Mara’s journal reflects her frustration with a life in which everyone seems to be changing except her: “i took out a lot of my piercings too, it seemed like the right thing to do, i was getting sick of them… sometimes lately i feel like i don’t know who i am anymore. i know that sounds totally lame and emo or whatever, but it’s true and i can’t lie about it.” If being able to see people like Mara learn and grow and change from their experience means that the series won’t last for 25 volumes and counting, then I guess – to borrow a phrase from both Campbell and his serialized fictional character, it does seem like “the right thing to do.”

Writer Brian K. Vaughan puts it another way:

Most people who love comics, we’re used to things like Spider-Man and Batman, things that have an illusion of a third act. There will never really be a last Spider-Man story or a last Batman story, even though people have tried it. It’ll never really end. And we get spoiled that way. But I think finales are what give stories their meaning. The stories need endings because all of our lives have endings.

When I think of a series that ended on a high note, Neil Gaiman’s work on Sandman comes to mind (although he has produced spin-offs and a new mini-series since the mid-1990s), not to mention Vaughan’s own Ex-Machina and Y The Last Man. On the other hand, I think Aaron McGruder’s social and political interests developed as a cartoonist during his time on The Boondocks in ways that did not reflect well on the quality of the strip. And I wonder about a series like The Walking Dead now that the television adaptation has become more well known than the comic. While superhero comics are obviously relevant here too, I’m more interested in creator-owned titles or story arcs created by a single writer and/or artist who is inextricably linked to the series’ identity.

So let’s talk about endings. Which creators or titles get them right? Where are the missed opportunities? We could even consider the larger implications of Campbell’s concerns about the inaccessibility of long-running serials or Vaughan’s suggestion that comics storytelling can sometimes suffer without the sense of finality that endings provide.

It’s interesting that Vaughn sees not having an ending in superhero comics as people being spoiled. I think people actually resent the lack of an ending; or at least can get upset when things change or keep changing.

People generally see Jaime Hernandez not having an ending as a good thing, right? Most critics/readers seem to feel it adds layers of nuance over time.

I read “spoiled” in the sense of, why bother to get emotionally invested in an ending (or a character’s death) when you know it’s never really over? We enjoy these characters and we want the dimension and complexity that comes with their growth, but we also don’t want them to go away or change too much… I sort of felt like Vaughan was saying that we can’t have it both ways. Or can’t always have it both ways.

Then again, potentially good things can come out of a reboot: like a female Thor!

I thought about the Hernandez brothers too. I wish I had read more of the series to comment on it here, but I’m a newbie to their work. I get the impression that faithful readers are okay if they never stop developing more and more stories.

Yes; I think the sense of having lived with the characters over time is definitely a big part of the appeal.

Great post, Q! I’ve only read the first volume of Wet Moon but I’m curious to try more. The Jaime H comparison is an interesting one — I do think that his readers respond to the open-endedness, but I also think that part of the euphoria that greeted Love Bunglers was because it seemed to function as a de facto conclusion to a lot of the book’s long-running plotlines. (Though as Ng Suat Tong pointed out here at HU, it’s really only the most recent in a series of apparently definitive conclusions.)

That’s a great point about the enthusiasm for the resolution; I hadn’t thought about that.

I know I’ve definitely felt let down at points by the way an ending isn’t an ending. I remember that about Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing, and Grant Morrison’s Animal Man run; stories which really seemed to come to an emotionally satisfying end, and then someone else took over and on it went.

Probably I wouldn’t care now, but way back when it felt like a bit of a betrayal.

Great post!

Noah–I dunno, I think with something like Moore’s Swamp Thing it can be pretty easy to just stop reading with his issues and see that as an ending. DC gave him enough control to give what can be read as a “real ending,” (unlike some other times when writers have changed.) Although I did like a lot of Veitch’s stuff.

“Yet comics struggle with the pleasures and burdens of serialization in distinctive ways.”

As a big daytime soap opera fan–or at least a former one–I would say many of these “pleasures and burdens” do exist in that medium as well. There are so many similarities between daytime soaps and the big comic book franchises. But aside from the obvious things like characters coming back from the dead (or over-ominence of other badly told rape stories)–you have a genre that both revels in and likes to ignore decades of history and a title that doesn’t belong to one headwriter. Lots of non-soap fans don’t realize that many hardcore soap fans do follow certain writers from the show to show, or stop watching when one writer leaves and suddenly all her stories are ret-conned by the new writer.

However, watching soaps (which unlike most current primetime serials, are never meant to come to a strong conclusion,) I kinda appreciated the open ended format. I would find it frustrating with a show with a strong plot set up in the early issues/episodes, but with these open-ended titles it doesn’t bug me. After 25 years of watching All My Children through some great eras I would seriously call some of my fave tv ever, and even more terrible eras where I just stuck around out of nostalgia and loyalty, I was happy that it came to an end without tieing things up–the sense that things will just continue.

Eric, I had a feeling that my “distinctive” claim might not hold water for long! I appreciate this comparison and you’re right – it can be incredibly satisfying to watch soaps in seasons and cycles, where one resolution quickly turns into another plot point. There’s no real expectation of an ending, although some characters do leave or a town blows up or something…. I guess this suggests a distinction between stories that focus on world-building with lots of dynamic characters vs. those that are driven by one or two strong plot lines. In the latter case, repeatedly putting off the resolution in order to extend the series can be frustrating. (I felt that way about Swamp Thing, which is why I started to fall off after Alan Moore left too….though I liked the Veitch issues for a while.)

Yeah Moore’s Swamp Thing and Morrison Animal Man can basically be read by fans of those writers as complete stand alone works.

Since I read them in trades, I was never tempted to see them as part of an ongoing serial. Possibly if you were reading them each month there’s be more a sense that a new writer had taken over.

I have never read (or even heard of) Wet Moon, but I am all for endings – but also not. . . maybe that’s cop out. . . But Xaime Hernandez for example, can always follow other characters and places, and then come back to Maggie and Hopey much later, or not. . . L&R has endings and lack of endings in a way that emulates real life. He use serialization in this way suggests both the real possibility of endings, with the veneer of immortality that we use to cope on the day-to-day.

Actually (and I am sorry that this is a tangent), that is what I have argued in my dissertation (and other places) that LnR is best read as an anthology of work by both Bros (and sometimes Mario). Together they succeed in exploring various forms of (gendered) Latino identity through the separation of their worlds that run parallel and thus for the most part succeed in avoiding stereotypes.

I made a point to collect the old style LnR collections that don’t split Locas from Palomar until Volume 7, when you’ve had a chance to read plenty of both.

Not a tangent by any means, Osvaldo (this is exactly the kind of discussion I was hoping for). And I’m glad the conversation has turned to Love and Rockets because I have always had a hard time – with all the reprints and collected editions – trying to figure out the best place to begin the series and which path to take. So I haven’t made the effort that I should (suggestions are welcome). It’s interesting to hear, too, the social implications of reading the title as an anthology.

I hope you’ll considering picking up Wet Moon!

Qiana–well said about the comparison of the two styles (ie world building vs ones introduced with a key plot line.) I admit with comics, sometimes I have trouble telling the difference between the two, at first. I never LOVED Fables, but I enjoyed it, but I also expected it to come to a definite end (perhaps because I picked it up after finishing Sandman.) I’ve just lost interest now–and I think *part* of that is due to the writing, but another part is due to my expectations of the story arcs reaching some sort of joined conclusion at some point before 100 issues.

I have a friend who has recently really been into Alan Moore, so I lent him the Swamp Thing collections. It took him a bit to get into, but he ultimately loved it–but once they were done he had no interest in continuing with the collected Veitch issues (which ultimately I found unsatisfying anyway since they never reprinted his final issues, and of course his true final story was never published anyway,) nor reading Hellblazer, as much as he liked Constantine. (I would make a strong argument that Hellblazer can be enjoyed if you read just one writer’s run on it–and I’m glad all of Delano’s underrated stuff has now been collected.)

I can understand that. I’m largely not a Frank Miller fan–but I did really enjoy his run, and brief followups on Daredevil and yet have had no desire, despite the urging of friends, to revisit other acclaimed Daredevil runs by other writers. Some of it may be due to the fact that I fell in love with comics mostly through manga in the 90s (much of it French translations and shoujo works,) so I’m used to a story like Banana Fish or Please Save My Earth running around 20 volumes–but actually heading to a conclusion, and I would never want to read any of those characters under a different manga-ka. (On the other hand, many manga titles currently seem to go on endlessly–one reason, of many, that I keep far less up to date on manga titles.)

You see the dilemma on primetime TV serials, particularly those on network tv that have more recently tried to be more like cable serials. Lost being an obvious example where, while both headwriters have now admitted they had no idea where the show was going, it was set up with the promise of a central mystery to be solved but was stretched too far (at least for my patience) by the success of the show and the network demanding more episodes. Stephen King has admitted that the Under the Dome tv series was only meant to be one 13 episode series (which is how I remember it being advertised.) I never particularly liked it, but I gave up on it when I heard that, due to ratings, they were turning it into an open ended series despite its premise–from all that friends have said, I’m not missing much.

I re-read the ending of Moore’s Miracleman recently and that might be my favorite resolution to a serialized comics narrative (from issue #16 of the Eclipse run from the 1980s). The prose piece that introduces his final issue not only ends the story but dismantles so many tropes of 50s-era comics–while celebrating them at the same time! It’s filled with Miracleman’s reveries, ornate lines like, “I dream of cities that old futurists would weep with joy to see, of wharfside neighborhoods where tough kids track down spies, where crumbling tenements contort to teetering and eccentric shapes that seem to spell out words against the night.” He even has a paragraph alluding to those terrible but endearing Marvel monsters like Fin Fang Foom.

I haven’t been able to bring myself to read the Gaiman issues because Moore’s story seems so personal and definitive. So I guess that’s one way to end a series…bidding farewell to the characters and to certain elements of the genre itself!

The most relevant point of comparison here would be comic strips — how many of the great strips were ended by design (rather than loss of syndication or death of creator)? Calvin and Hobbes, I suppose (“great”), but then what…? Continuity strips are generally engineered to run indefinitely.

IIRC, Adam Warren had a bit in the most recent Empowered about endings — being bugged by fans wanting to know if he had an ending in mind. He made a joke about nobody asking Stan Sakai if Usagi is ever going to end (although, personally, I would like to see a final climactic showdown between Jei and Usagi, not to mention the return of Hikiji)

The thing about comic strips, though, is they are rarely serialized (unless we’re talking about Little Orphan Annie, Mary Worth, etc, which I think all died out due to–well few people reading comic strips for story anymore, however good or bad, and the fact that most of them ended with two panels a day. I remember trying to follow Mary Worth and Rex Morgan as a kid in the late 80s before our paper dropped them and you got such little information each day about anything, I had no idea how anyone found them interesting even as a piece of ridicule. Though I think they are still running–somewhere…)

People generally see Jaime Hernandez not having an ending as a good thing, right?

He does end his stories. He just tells new ones with the same characters a little while later. Gilbert too.

The best part is that their characters age “real time” when they’re not being depicted. I think how they do it is a lot better than the endless-youth soap opera of the fights ‘n’ tights genre and they should adopt it more;

Captain America throws his mighty shield once again and beats the bad guy. He goes off stage to enjoy a beer for a few years while Thor spends some time hitting things with his hammer. Much better than having them stand around frowning.

great essay, Qiana! and thank you so much for giving some attention to Wet Moon for it, i appreciate it. :) i feel like serial comics ending is something i rarely see people talking about, or when they DO end everyone just kinda shrugs or is sad or says “the ending sucks!” but they don’t get more into it than that.

not to focus too much on my own work here, but i feel like at this point there isn’t any ending to Wet Moon that will ever be satisfying, regardless of whether it ends at volume 8 or volume 30. there will always be something unsatisfying for readers, and i wonder if other cartoonists who do serial stuff feel that way about their work, too, and maybe because of that they’re scared to end it. i’ve actually never really ended anything i’ve ever written, even seemingly standalone books i’ve done were meant to have sequels that got canceled and never happened, so i have no idea what it’s like to END anything. part of me is excited to finally come up with an ending to something, but at the same time it feels scary and sad.

i think i half agree with Vaughan’s quote and half disagree. i feel like some stories definitely need endings, i can think of a lot of serialized stuff where i wished the ending would happen or that it happened sooner than it did, it always sucks seeing a story you love peter out. but on the other hand i also like stuff, particularly TV shows as i don’t read a lot of serialized comics anymore, that go on and on without an ending in sight because it can create a nice “lived in” feeling and i like following characters when there isn’t a big plot looming over them and when the story doesn’t seem to be in any rush to get somewhere. it’s not comics of course but i’m really into Grey’s Anatomy and it’s about to start its 11th season and i’m loving it more than ever, and after watching 10 seasons it’s like you live with the characters and being a drama show it never ramps up to some epic plot or confrontation or something, so it feels satisfying to just leisurely live in that world with the characters. since there’s no big plot and it’s more about exploring the characters and having fun with them, if it ended abruptly i don’t think i would mind that much because there isn’t really anything that NEEDS to be resolved. so in that sense i don’t agree with Vaughan because i think there can be stories that narratively don’t need endings and are better for it.

Your description of the “lived in” feeling immediately brought to mind for me the show Homicide. Its sense of pacing and character development was so good and the world it created was so dynamic that I never wanted it to end. (Not that The Wire isn’t good too.) Certainly writers come and go on these series, but there seemed to be a strong guiding vision to the whole thing. (Shonda Rhimes of course, in the case of Grey’s. David Simon on Homicide and The Wire.) On the other hand, it was a crime procedural, so there were always new cases and story arcs. Finding that balance is what’s important I guess.

Now that I think about it…. the world of Game of Thrones is immense and overwhelming and wonderful too, but I’m actually kind of relieved that series has an end date. (So Wet Moon is in good company!)

I appreciate you stopping by, Ross! It’s great to get even more insight into your creative process and the thinking behind your decisions.