Saint Jerome, the patron saint of translators; engraving by Albrecht Durer (1514)

In a recent article posted on the Hooded Utilitarian, Marc-Oliver Frisch had cause to quote the philosopher Theodore Adorno:

“Not only does democracy demand freedom of criticism and require critical impulses, it is effectively defined by criticism. […] The system of checks and balances, the two-way control of executive, legislature and judiciary, says as much as: that any one of these powers may exercise criticism upon another and thereby limit the despotism to which each of them, without any critical element, gravitates.” (Translation by me) [i.e. by Frisch]

In the comments, one “oh please oh please” (sic) posted a rather personal and acerbic reaction to Frisch’s article, containing the following statement:

In this way “Hater” is a useful term of art pointing to criticism as an act of status anxiety rather than engagement of the work (for example inserting a bland Adorno quote as a means of boasting one has translated it oneself).

Noah Berlatsky (editor of the site and comments moderator) rebuked the commenter for this charge of “boasting” thus:

Saying that Marc put in the Adorno quote just to say he translated it is really incredibly uncharitable. It’s also kind of ridiculous. There are just lots of people who read multiple languages; it’s not a big deal. If you think it’s a big deal, that’s kind of your problem. But in this context, it makes you look like you’re sloshing around in the status anxiety you’re claiming to combat, and also like you’re engaging in some knee-jerk anti-intellectualism.

I wholly agree with Noah here — multilinguism is common all over the world, in every class and at every level of education. It’s quite normal, for example, in the Philippines to meet people fluent in four languages: Tagalog, Spanish, English, and whatever the local tongue or dialect is. There are probably more polyglots than monoglots in the world’s population.

In fact, truly snobbish behavior would have dictated that Frisch leave the quote untranslated in the original German. That was in fact the default practice for academic papers well into the 1960s and is not unknown today. (Until the ’50s Harvard University required that all entering students master Greek, Latin, French and German as a matter of course.)

But I’m not writing this article to revive an old dispute. That comment has bothered me for the past couple of months because it shows an ignorance of one of a translator’s most important duties: to be answerable.

I’ve been translating professionally for over thirty-five years — from English into French and vice-versa, with the occasional venture into Italian — to eke out my main living as a language teacher. I’ve translated novels, plays, screenplays, comics; teachers’reports, lessons, curricula vitae, memos, letters of intention, business articles; technical manuals, packaging graphics, powerpoint presentations; the oddest and most delightful commission being a painter’s prayer. In short, a bit of everything.

Translation is seldom thought of as a dangerous trade — but it is.

Imagine that I make a mistake in a manual for operating heavy machinery. For instance, I lazily translate ”metres” as ”yards” because the two measures of distance are approximately equal. As a result, a worker gets maimed or killed.

Or a medical treatment plan calls for semi-monthly (twice a month) checkups, and I render that as bi-monthly (every two months). You can imagine the grim outcome.

Legal documents offer particular landmines. Suppose a French company sends a letter of intention to an American one offering to take a 20% stake in it, and states that ‘eventuellement’ they will increase that stake to 100%. I foolishly translate ‘eventuellement’ as ‘eventually’. The American company now believes there’s a firm takeover bid on the table. No: ‘eventuellement’ translates as ‘maybe’. One can see the possible catastrophe of litigation this misunderstanding could bring about, and the translator would quite rightly be held responsible — legally and financially.

It’s why legal translators and interpreters are almost universally certified and bonded specialists, and why general translators such as I will not touch such matter with a ten-foot-pole. (Well, I have overcome my caution a few times out of greed, but always with a disclaimer attached to the document.)

It’s true for criminal law, as well. Many are the convictions that’ve been overturned on appeal because of incompetent courtroom interpretation.

Translation errors can even change history. It appears that Saddam Hussein erroneously thought he had American approval for his invasion of Kuwait because of an interpreter’s mistake. (For more famous translation errors, please go to this site.)

And a famous translation error led to the doctrine of Jesus’ Virgin Birth.

In the Hebrew Bible, Isaiah 7:14, the coming of the Messiah is foretold thus:

Therefore the LORD Himself shall give you a sign: Behold, a virgin shall conceive and bear a Son, and shall call his name Immanuel.

(King James translation)

But in the original Hebrew text, the word “virgin” (betulah) is not used, rather “young woman” (almah).

Now, in the 3rd century BCE King Ptolemy II of Egypt commissioned the translation of the Hebrew sacred texts into Greek (the result being known as the Septuagint). And here the fateful error crept in: alemah was rendered into the Greek parthenos (virgin). A similar mistake would have been possible in English, where “maiden” originally meant a virgin woman, but through sense creep has come to mean simply young woman.

Four hundred or so years later appeared the Gospel of Matthew. It was written in Greek (the liga franca of the Middle East) and drew heavily on the Septuagint’s version of Isaiah:

Behold, a virgin shall be with child, and shall bring forth a Son, and they shall call his name Emmanuel, which being interpreted is, God with us.

(King James translation)

Yes, the old parthenos error had wormed into this Gospel. Hence the doctrine of the Virgin Birth, rejected by some, accepted by others, the source of so many wars, massacres of “heretics” and Inquisitions… people were burnt at the stake because of a trivial translation mistake.

I trust you see what I’m getting at with regards to Frisch and Adorno. Translation is a serious business that can have serious consequences. It is therefore incumbent on every translator to sign his work — to accept accountability. Far from meriting scorn, Frisch is to be commended for intellectual rigor and responsibility.

Translators everywhere: own your work!

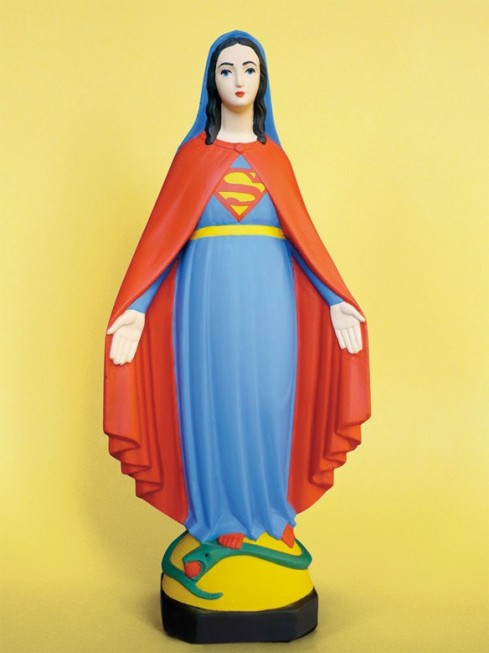

Not a virgin, but still super: Mary as seen by artist Soasig Chamaillard.

Interesting stuff!

The ability to read French and/or German remains a requirement for completing a lot of PhD programs in the humanities. Sometimes one can use math to replace one of those, so long as you’re area of study demands working knowledge of advanced calculus or statistics (philosophy of science comes to mind here). The idea isn’t that the student will be able to throw out their translated editions, but that they’ll know how to understand the limits of translation, and what’s at stake.

Thanks for this. . . I have recently undertaken a translation for my own pleasure of an article in Spanish by Jodorowsky that I could not find an English version of, “La Vida Sexual Del Hombre Elastico” (aka “The Sexual Life of the Elastic Man”).

As the only translating I have ever done before was a page long passage as part of the exam requirements for my Master’s degree, I am finding this a lot more difficult than I imagined, despite my fluency in Spanish. Part of the problem is that while I read and understand Spanish I have have never studied it very much, thus capturing the nuance of his metaphors and humor in his purple prose is really hard. I keep having to balance between adhering to the literal and trying to capture the tone. The article is only four pages long, but after the first page I was exhausted and put it down, and haven’t had a chance to get back to it.

Gave me a whole new appreciated for folks like Edith Grossman

I’ve been very interested in the work of translators since I went on a big Jorge Luis Borges kick about 5 years ago. Having translated a number of texts into Spanish himself, Borges often explored the theme of how translators effect the text they adapt. His short story “Averroës’s Search” is about the Islamic philosopher Averroës and his attempt to translate Aristotle’s “Poetics” despite being unfamiliar with the concept of theatre.

Borges also has two essays about translation worth checking out titled “Versions of Homer” and “The Translators of the 1001 Nights.”

Is naming Theodor Adorno Theodore a translation error?

Possibly! Not a dangerous one though luckily….

“Is naming Theodor Adorno Theodore a translation error?”

I was inclined to blame that one on Noah when I first noticed it. Then I discovered that it was my own mistake. Life sucks.

But — but the 72 divinely inspired translators of the Bible all made the same “mistake”, Alex! Clearly a case of God revising His own Word.

Jones, those 72 largely drew upon Wycliffe’s translation; and he as a Catholic. I believe the Virgin Birth a also part of Anglican doctine, so no rocking the Biblical boat! (Except, of course, Noah’s ark.)