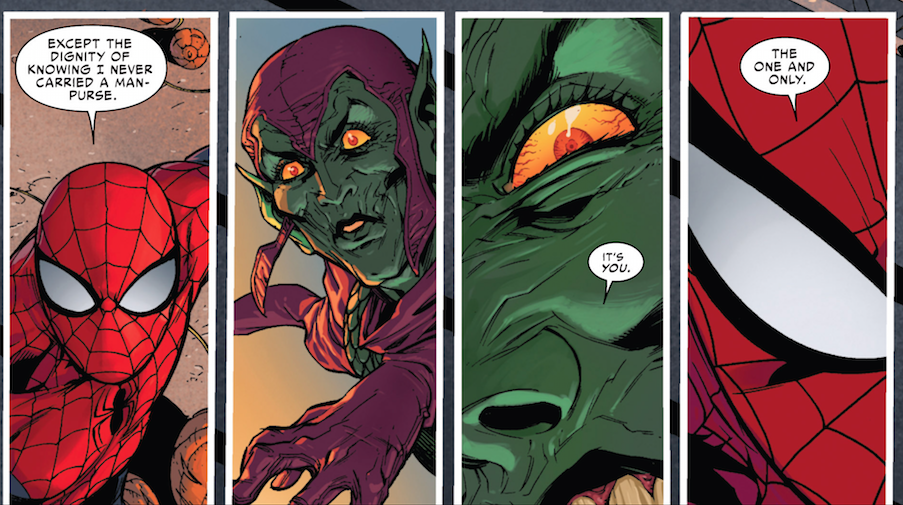

In the above scene by Dan Slott and Giuseppe Camuncoli, the Green Goblin at first thinks he’s fighting Doc Ock in Spidey’s brain (as Osvaldo Oyola explains in his

Which makes sense, to some degree; Peter’s wise-cracking has been one of the characters consistent tropes through the years, more reliable than even his (occasionally black) costume — a point of stability in what Osvaldo correctly points out is decades of ret-conned, indifferently written incoherence

And yet, looking at that sequence, I realized that Spidey’s humore has never exactly made sense to me. Peter Parker is not, as he’s generally written, witty or even particularly cheerful. His backstory is all about trauma; he’s a bullied, bitter, guilt-ridden, whiny nerd, worrying about his Aunt May and filled with insecurity and neurosis. And then all of a sudden, he puts on the costume and he’s nattering on about man purses like he’s got not a care in his webhead.

You could explain this psychologically if you wanted to I suppose, and I’m sure someone has — the happy-go-lucky Spidey front hides Parker’s deep pain; the double-identity gives him the opportunity to explore aspects of his personality that nerdy Peter has to repress. You could also, and somewhat more convincingly I think, explain it as a by-product of Marvel’s creative process; Steve Ditko laid out this bitter, depressing story, and then Stan Lee came in afterwords and filled in the text bubbles with obliviously cheerful blather.

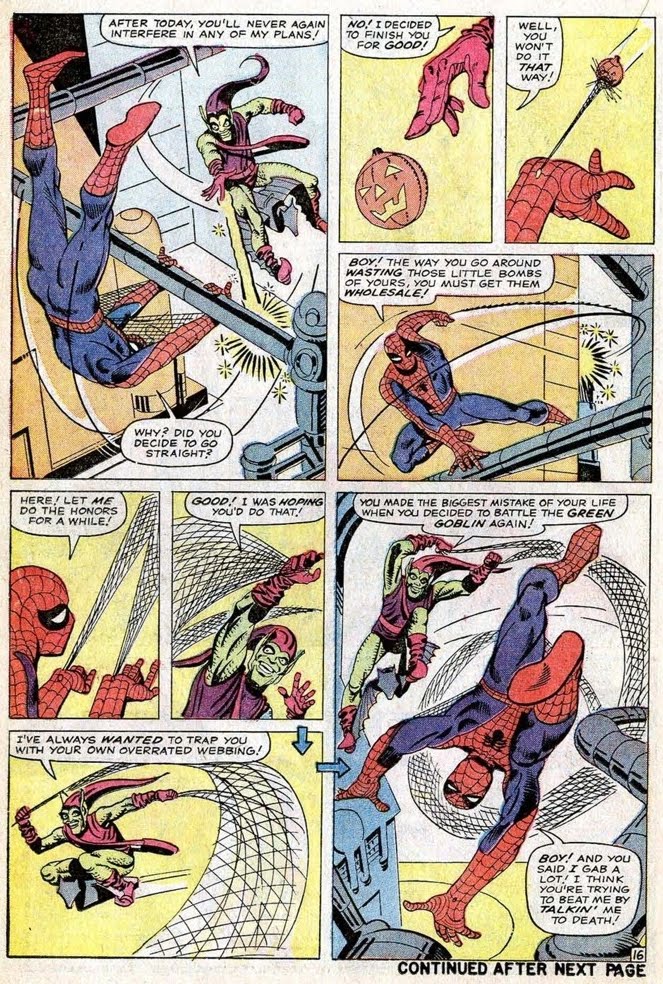

Either way, though, the point is that the multiple-personality disorder that Osvaldo diagnoses in the character is not, or not just, a function of decades of continuity burps and generations of hacks writing on deadline, only occasionally paying attention to what the hack before, or the hack after, happened to do. It’s also something in the character from the beginning. Spider-Man was never coherent; he always had a double identity.

Double identities are a standard superhero trope, obviously. Nor is it unheard of for the superself and the nonsuperself to have different personalities. The Hulk is the most famous example, but the truth is that Superman and Clark Kent, early on, seemed less like one guy in two outfits, and more like two different people — one helpless, nerdy masochistic nebbish; one sadistic wise-cracking swashbuckling asshole. Superheroes from early on, and even iconically, are not one person; they don’t have a single identity. They’re more than one; their selves are multiple.

As folks pointed out in the comments to Osvaldo’s post, this has some interesting moral implications. Kantian morality, in particular, is based in a particular notion of identity and the divided self. For Kant, the true self is the moral self, or the moral law that speaks within you. Immorality is the accretion of transient desire, or really transient personality, that ties you to the phenomenal world, and distracts your brain, or more your conscience, from noumenal contemplation. From this perspective,you could see the split personality superhero as a kind of Kantian parable. Peter Parker is the phenomenal self, riven by neurotic doubts and distractions; Spider-Man is the noumenal self, devoted to the single-minded pursuit of duty.

That doesn’t actually sound much like the Peter/Spidey we know, though. Spidey is hardly a serene slave to duty; on the contrary, as Osvaldo explains, Spidey is all over the place, sometimes a self-sacrificing martyr, sometimes a cheerful babbler, sometimes a brutish thug. He’s hardly a consistent example of WWKD.

Maybe that’s the point, though. Chris Gavaler has argued that the figure of the Clansman was an important pulp precursor and inspiration for the superhero trope of double identity. The KKK, of course, used the double identity as a way to wreak evil — being somebody other than who they were allowed them to sidestep duty and the moral law, and embrace the exhilarating phenomenal pleasures of violence and evil. Kant presents good as arising from an eternal, unwavering identity. It makes sense, then, from his perspective, that to abandon morality you would first abandon a stable self.

And that, again, is what superheroes do. Peter Parker puts on a mask to go hit people really hard without legal authority or due process of law. That’s not duty; it’s vigilantism. And that vigilatism is enabled by forswearing one identity; Peter Parker wears a mask so that he doesn’t have to be Peter Parker, with all the attendant moral and social obligations, just as the KKK put on the hoods to escape their dull selves bound by law and duty not to shoot and lynch their fellow citizens. As Doc Ock’s possession of Spider-Man suggests, superheroes escape their identities in order to become supervillains. The more continuity renders their selves incoherent, the more true to themselves they are — that self being, at its coreless core, bifurcated, morally adrift, and un-Kantian.

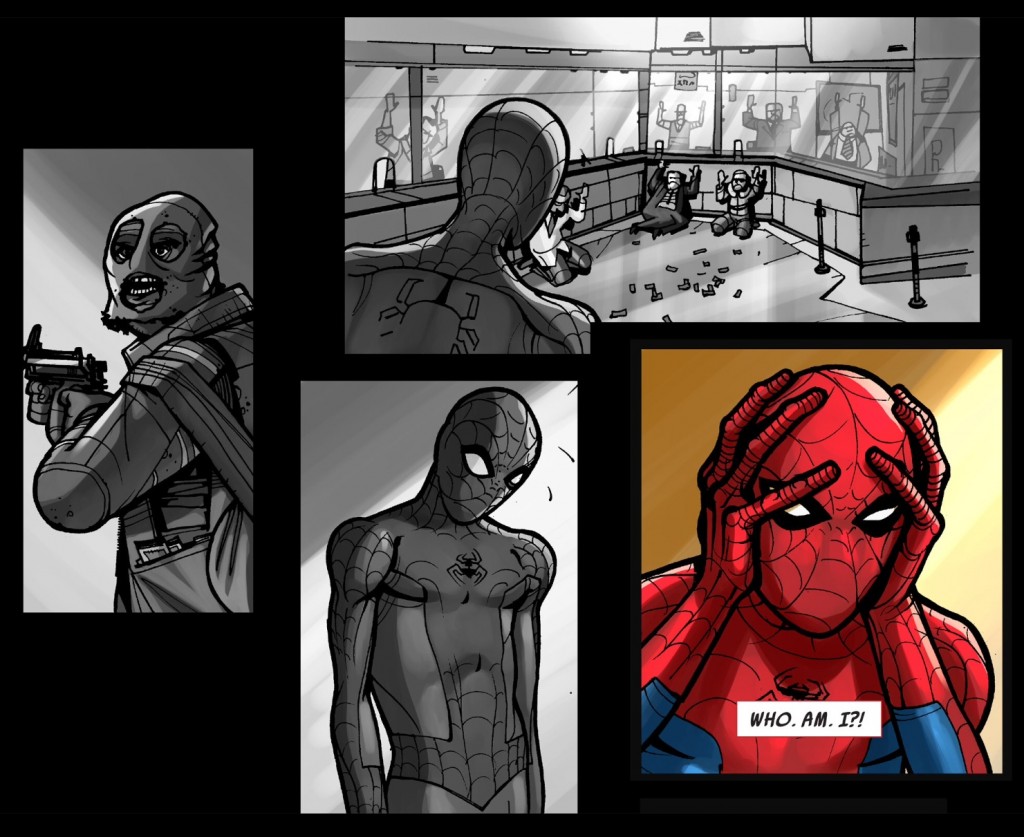

From Spider-Man, “Who Am I?” by Joshua Hale Fialkov and Juan Bobillo and JL Mast

And so Spider-Man’s trash talking humor is a mask too. He pulls on a new and playfully entertaining personality to disguise the immorality of his vigilantism. Or rather, Stan Lee pulled that mask over him and other writers followed.

And humor remains a Marvel trademark. Joss Whedon’s expanding Avengers empire is all about comedy, including (according to the buzz) the last installment, Guardians of the Galaxy. While Warner Bros. are doubling down on Christopher Nolan’s humorless vigilantism.

Yes…it’s also interesting how moral questions around superheroes are pretty much always seen as being about authenticity or continuity errors, right? Lots of discussion about whether a female Thor is a betrayal of fans/a cynical cash grab or a progressive advance, relatively little about whether bashing people in the head with a hammer is a reasonable way to deal with conflict.

First, Noah – my notes tell me Giuseppe Camuncoli drew those panels at top. . .

It is hard to take this Kantian angle seriously. The idea of a “true self” is something I associate with freshman comp personal essays – the uncritical and static view of being in a social and historical context that somehow has a connection to agency despite ostensibly dictating actions, but also serving as the measure against which actions are determined moral.

In my view, the incoherence of serialized identities in superhero comics makes the incoherence of lived experience explicit in its over the top conflicts and the ability for the reader to hold up different episodes in comparison across a representation of time that is simultaneously changing and unchanging.

The Kantian idea that you can determine if acts are moral if it would be good if everyone did them starts with an a priori notion that there is such thing as absolute morality. There are things that become immoral if everyone does them. There are things are moral/immoral based on dynamics of power.

In light of this, the jerky wise-cracking Spidey and the jerky preoccupied Peter Parker identities make perfect sense to me (plus, they are both kind of jerky). As such, Chris’ comments above seem right to me, the shifting nature of identity is required to function in a complex moral world. We all wear masks.

Huh; I tried to identify the artist but it wasn’t so easy; I’ll change it.

I would say that Kant’s notion is a good bit more complicated than a “true self.” He’s saying that the true self is God; that is, everybody’s true self is the same, because morality is universal and comes from God. The self that is God, or knows God, is the real, true self; the atomized individual passions and so forth which we tend to see as identity under late capitalism (i.e. fandoms) are not authentic; they’re transient manifestations of the phenomenal world.

That certainly goes against the grain of how we think about self and morality at the moment. We prefer to talk about complex moral worlds and fluidity and sneer at the idea of authenticity or truth. I’m prone to do that myself. What I’m saying here, though, is that in the context of superhero identity, the complex morality you’re discussing is at bottom a mask over an essential vigilantism and violence. There certainly are various identities and various moralities, but don’t they all add up to something that isn’t very moral? I think Kant would say that yes, the end result is neither a true self nor a true morality, and that those things go together. You can say, well, there is no true self in our post-modern bricolage…but it’s possible that that means there’s no morality either, it seems like. Certainly, that looks like the case if you’re going to vigilantes as moral icons.

Or I guess to summarize, Kant says that morality and identity are linked. That seems buttressed by superheroes, where the identity is incoherent and so is the morality.

Spider-Man’s humour always made sense to me. It’s all in the mask.

If you look at the way many cultures perceive masks, humanity often uses them to channel some part of us we can’t usually access. I think you get the same thing with the internet. Many people behave dramatically differently on the internet to the way they behave in person, because of that layer of anonymity. I know lots of people who are shy in person, but hilarious online. When people can’t see the real you, you have the freedom to present yourself however you want.

Anyhow, Spidey seems more jovial than Peter Parker, because when Petey is dressed as Spider-Man, he doesn’t NEED to be Peter Parker. He’s playing the role. He’s being the mask. And that mask is probably who he really WANTS to be, because what shy, bullied kid doesn’t sometimes dream of being the centre of attention?

Why is Beyonce the first listed tag?

That aside, I love this piece. Elegant and insightful.

“I know lots of people who are shy in person, but hilarious online ”

It’s been a very long time since I read the original Ditko issues, but I don’t think Parker is actually that shy. One of his first lines is him saying to a gang of students “”look, there’s a great new exhibit at the science hall tonight! Would any of you like to go with me?”

He’s depicted as being an outcast because all he can talk about is “brainy” science things. There’s no indication that he has an interest in comedy as far as I know- or really much of an internal life other than liking science and having weird parenting issues.

If he was listening to comedy albums alone in his room or whatnot you’d have a stronger case.

Thanks Kailyn! I thought for a second there I was going to talk about Beyoncé’s video album and multiple identities…but then I didn’t. Whoops.

I always read that line as something Peter was saying in a nervous tone, because he wasn’t good at relating to people. I mean, I think he had to pluck up his courage to reach out to people. *Especially* in the Ditko era (with later artists and creative teams, he came out of his shell). I wouldn’t call that smiling Peter Parker with his gang of friends in the Romita run particularly shy, but he certainly was back at the start.

Either way, masks and secret identities do allow us to explore aspects of our personalities that we don’t generally openly project. Shy or not, Peter Parker may always have had a good sense of humour, but that wise-guy lip is at odds with his goody-two-shoes respectable future-scientist persona. Wearing that mask, with no one knowing who he is? He doesn’t need to worry about that. He’s anonymous.

A lot of the times where Peter acts more dour or broody as Spider-Man, it’s because, in spite of the anonymity, his Spider-Man actions are creating consequences in his Peter Parker life, OR because people like J. Jonah Jameson are negatively personifying ‘SPIDER-MAN’. So in other words, the mask slips, or it becomes just another face with problems.

I genuinely think the humour of Spider-Man is an expression of Peter’s id.

“I genuinely think the humour of Spider-Man is an expression of Peter’s id.”

I think this is a common way to read it (and I’d be interested if anyone has an example of it’s actually being articulated in the comic.) As I said, though, it seems reasonable to also see it as Ditko and Lee not coordinating their work very well — or as an example of the general incoherence of Spider-Man’s personality over time thanks to the vicissitudes of continuity.

Well, I think he was engaging with jokey Stan Lee banter with Aunt May, Mary Jane, Flash Thompson, etc. by the time of the Romita issues, at least.

“engaging in”

I haven’t read enough Ditko-era Spider-Man, but I by the time I was reading ASM regularly in the early 80s there was a lot more slippage btween the Peter Parker and Spider-Man personae – with PP making snarky remarks about/to JJJ under his breath, or singing stupid songs with the lyrics changed when he was in a good mood because he finally got paid and could pay his rent and what not, while the Spider-Man identity was very serious about the darker tone superheroing was taking, like the Sin-Eater arc (which I plan to write about at the end of September).

It has been forever since I read it, but at some point Peter specifically states that the reason he cracks so many jokes is because he is terrified and so it is either crack jokes or be scared witless. I want to say he makes that statement in “The Boy who Collects Spider-man” but I am probably wrong.

Truthfully, I prefer the “split personality/demonic other” reading that comes with the placement of the mask. That follows more with the archetypal view of superheroes as the modern day heroes of myth. Peter’s actual explanation humanizes his alter ego (the terminology there giving proof that we are dealing with some kind of “other” personality) a bit too much for me.

showing how long it has been since I read a Spider-man comic, the story I am referencing is actually called, “The Kid who Collects Spider-man.”

Actually, there’s no way Kant would think it morally permissible to hold a secret identity, for pretty much the same reason he think’s it is never ever morally permissible to tell a lie — because it’s impossible to will the maxim as a universal law.

Hi Noah, I think if you’d look again at pretty much any of the Ditko run past that 15 page first appearance in Amazing Fantasy, you’ll notice that Peter Parker is regularly portrayed as saucy, assertive, aggressive… taunting and exchanging barbs with his classmates, flirting with his boss’s secretary, playfully ribbing Aunt May, and even eventually getting the better of J. Jonah Jameson in their business dealings. He’s isolated because of his secrets, and that extends to non-super heroic problems like his aunt’s failing health, but not for any other kind of introversion. And far from there being an artist-writer dichotomy, Ditko is very much a part of this portrayal with the expressions, body language, and most likely situations he creates for Peter. If Peter did change from an introvert to an extrovert when he put on the mask, that’d be a pretty standard psychological trope, but I think the idea of Spider-Man as teenage Everynerd is a combination of that oft-reprinted first appearance and some imaginative press, encouraged by Stan Lee’s promotional burblings. The thing is, Peter Parker got out of high school after about the first thirty issues of Spider-Man.

Huh; that’s interesting. That was not always the portrayal later on, for sure.

Laughing in the face of danger is a common and effective coping technique. Spidey’s wisecracks always seemed natural to me.

I disagree with the use of Spider-Man as an example of the immorality of superheroes. He defends people from violent crime — generally considered morally and legally permissible, and often obligatory. He sometimes pursues criminals, but the private pursuit of criminals has always been an accepted part of American civil society. When de Tocqueville wrote in 1830 that he’d rather be a fugitive in France than America despite the fact that France was better policed, that’s what he was talking about.

Punisher makes hit lists and then carries out the hits. Batman ignores search and siezure laws. Both have been known to torture or at least terrify to gain information. Spider-Man struggles with his temper occasionally, but he is consstantly weighing how far he can morally go in his pursuit of justice and the safety of his fellow man. He cooperates with the police, though they are loath to admit it publicly. He is generally portrayed as having some lines he absolutely will not cross, no matter the threat. I admit to some variation from one creator to the next and occasional overuse of artistic license, but as an example of a person with power trying to do the right thing with it, Spidey’s usually as good as we can expect in a flawed human race.

…unless you see hitting someone with superstrength as at all problematic. In real life, when someone with just regular strength hits someone in the head it can cause serious medical problems, starting with concussion and going on up to permanent brain damage and death. Why it is okay for someone who is not a representative of the law to use deadly force against people without due process of law?

Superhero morality is just a mess, basically. Of course, it’s all in good fun in general, not to be taken seriously, etc. — but I think it’s worth thinking occasionally about what it means to so repetitively and obsessively fetishize extra-judicial force as a solution to society’s problems.

That said, I agree that morality and identity are linked. Who you are often determines your moral obligations. That seems to fight against universality, but really it just makes it more specific. Lots of things an oncologist would (and should) do to a cancer patient would be morally reprehensible if the person taking action were not a medical professional, or if the person acted upon were healthy.

I also agree with Noah (and MVB’s) larger point that the mask not only limits consequences (moral and otherwise), it grants permission, at least psychologically. It would be presumptious for my everyday identity to take these actions, but for my other self, it is a duty. This is also why the costumer contributes to effective acting.

Noah, in the case of self-defense and the defense of others, I think the private citizen *is* acting as a representative of the law — one deputized by circumstance. Perhaps an attorney can correct me.

Regarding super-strength…well, violence is always problematic, but it’s not always wrong. If I swing a bottle at some guy’s head to stop him from beating his wife, I’m effectively using super-strength. But I’m not going to try and make the fight fair; I’m going to use the fact that it isn’t to help me stop the beating.

Regarding your extremely valid point about blows to the head, physiology in superhero comics and other action narratives is far more simplistic and far more grossly misrepresented than morality is. In the comics, everyone’s skulls and brains are made of rubber. It’s a wonder that Mr. Fantastic is deemed remarkable for anything other than intellect. However, I’m less inclined to worry about the cerebral health of someone in the process of committing a violent crime.

I want to note two unrelated items:

1) Dr. Octopus’s slow death (which leads first to his attempt to speed up global warming as a final mad scientist hurrah and his stealing of Peter Parker’s identity) is explicitly caused by his years of being beat up by superheroes (mostly Spider-Man). There is a scene where a doctor explains that all those years of blows to the head and body caused irreversible degenerative problems.

2) I think there is a difference between a citizen acting to save his or her self or someone else in a particular instance of crime, and taking upon yourself to put on a mask and patrol the streets with impunity. As I have written about before, it is really problematic for someone to go out with the pre-determined idea of “stopping crime” – much like modern police with thier tendency to use excessive force – when you do that everything starts to look like “crime,” as if crime were independent of social and historical forces. The very idea that what superheroes need to do with their extraordinary problems is deal with crime is by its very nature reactionary.

See, the problem is that superheroes *always* come upon people who happen to be committing violent crimes. Violence in the name of justice by vigilante citizens wearing masks is just about always justified. And yet, in real life, actual police not infrequently kill people for selling cigarettes or shoot unarmed kids walking back from the store.

Vigilantism as heroism in the U.S. is most iconically in real life associated with the KKK. Putting on a mask to take on the duty of violence is pretty much evil in any version of morality that makes any sense. The fracturing of identity in superhero comics is I’d say an effort to make an end run around that. I don’t think it really works (as a fair number of superhero comics have acknowledged and thought about, I should add.)

1. That’s awesome! I think there was something similar with a Flash villain, the Top, who experienced brain injuries from all his battles…

2. Yep.

Osvaldo and Noah — yes, the superhero “first responder” drive to fight crime and rescue people is reactionary in more than one sense. And there are always plenty of opportunities to exercise that impulse, just like how there are always interesting, complex murders on police procedurals. There are lots of reasons why superheroes are bent that direction. Some people think violent, reactionary crimefighting makes for a more exciting narrative. It certainly makes for an easier one to write. The typical superpower is more useful for violence than social science.

I have one other point that I’ve meant to bring up on this site for a while, as a comment to Noah’s excellent Black Panther piece and some other recent great posts: When we have people with extraordinary power act independently to fix the underlying social forces, we usually identify that as fascism. It’s what Franco did in Spain, Ataturk did in Turkey, Black Adam did in Kandaq, etc. In many cases, people like that make some genuine positive changes in a society, but at what cost, and what gave them the right? Of course, superhero comics have addressed this many times. The modern Superman’s policy of non-interference is always re-affirmed. “Really, it’s better if we just stop bank robbers and pull people out of burning buildings. We should let the little people deal with the politics.”

Personally, I think that stories about a character trying to save a city by fighting the political, social, and economic forces arrayed against its people — and more importantly, strengthening the agency of those people — would be fascinating. It would be like Game of Thrones or House of Cards in complexity, but with real heroes and more meaningful victories. If the protagonist’s power had clear limits, the fascism charge would be blunted, but the creators could still explore the just limits of intervention.

Such a proactive hero could even exist in superhero space, and take proactive advantage of the gains made by the reactive heroes. While the superhero fights a mobster who is extorting small businesses and selling drugs in a neighborhood, the social activist could work to change conditions so that the criminal is not simply replaced the next day. The proactive hero could also operate independently, exposing a corrupt slumlord, then arranging loans so the residents can buy their homes from the now-motivated seller.

That’s why I want to see a comic about Bruce Wayne, action philanthropist. Batman really ought to be the subplot in those comics, since Bruce is the one positioned to really change that city.

Noah, I think vigilantism as heroism in the U.S. is most iconically in real life associated with cowboys and western action heroes, not the Klan. Now if you change it to “brutal renegades as masked vigilantes in the U.S.,” we’d agree. I’m not saying that Chris Gavaler’s points about the origin of the dual identity narrative are wrong, just that most people do not see the Klan as heroes in the modern U.S.

You are, of course, correct that a lot of superhero comics have addressed fractured identity and the appropriateness of masked violent actors in society. Marvel’s Civil War was the most notable recent example. However, their events to prevent that from being a simple good and evil narrative failed. The forces that argued against uncontrolled vigilantism ended up being portrayed as fascists, or at least authoritarian enemies of freedom. Their valid points were mostly lost in the din of battle.

For a lot of these heroes, though, it seems like there’s a natural tendency over time toward exposed identities and a formal arrangement with legitimate authority. Captain America and Iron Man, the leading combatants in the Civil War, are ironically both great examples. Secret identities are particularly difficult to maintain in the Marvel Universe, as I think they would be in real life. And there are now no secret identities or unsanctioned heroes in the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

In regard to fascism and the superhero, you all should check out the Squadron Supreme miniseries from the 80s. The Squadron take over the US from the President, not exactly by force, but not really giving him much choice in the matter. They show that fascism works as a social system, kind of in the same vein of the Enlightened Despot. However, they come to a grim realization that their system only works if everyone in power has the same motives and good intent and that that intent lasts in perpetua.

As a vote of good faith to show that they are on the “right” side of the law, the Squadron reveal all their identities to the public.

Given that the Squadron are all Justice League analogues, it really becomes a very cool DC Elseworlds story done by Marvel and treading into the philosophic ground of why Superman doesn’t just take over the world and solve all our problems.

Interesting conversation. I’m surprised nobody’s brought up Clowes’ Death Ray yet, a Spider-Man-inspired comic which tackles the problem Noah describes, that “superheroes *always* come upon people who happen to be committing violent crimes.” Clowes’ teen superhero is given the powers component of the fantasy but never encounters any supervillains, and so is reduced to entrapping bums by leaving wallets full of cash on the street and beating up some kids who steal a TV. Sensing something missing, he fantasizes about the death of his grandfather/adoptive father in order to have a proper origin story to give him some resolve. Eventually he matures into a full-fledged serial killer. It gets at an essential ugliness to the genre in a way that the “dark” superhero treatments that have become commonplace don’t really do.