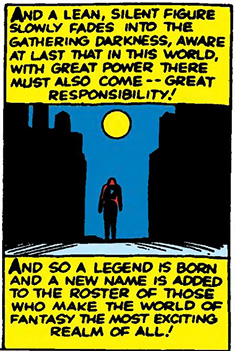

In case you didn’t know, in February of 2013, at the end of 700 issues of Marvel’s Amazing Spider-Man, Peter Parker died. Well, Otto Octavius aka Doctor Octopus, as he lay dying in a prison hospital, managed to switch bodies with his greatest nemesis, and then his body died with Parker’s consciousness or spirit or whatever still in it. Essentially, Dr. Octopus became Peter Parker, aka the Amazing Spider-Man, now referring to himself as—with no sense of irony—the Superior Spider-Man. The Amazing Spider-Man title that started in 1963 ended with that 700th issue and Marvel began a new series, The Superior Spider-Man, also written by Dan Slott (with pencils and inks by varying artists).

This was a controversial move among die-hard Spider-Man fans, especially those active in various internet forums and on Twitter. They were not happy with Dan Slott (though not as unhappy as many were at the prospect of a black Spider-Man, but that’s not really surprising). There have been plenty of things over the years that have made Spider-Man comics fans unhappy with the Marvel writers and/or editorial. The most prominent among these was the “soft reboot” of Spider-Man’s continuity in 2008 that magically dissolved Peter Parker’s 1987 marriage to Mary Jane Watson and put his secret identity back in the bag after the events of 2006’s Civil War (to name two events that many fans also complained about when they happened), but to actually kill Spider-Man and have someone else take his place unbeknownst to everyone else in the Marvel Universe? That is akin to saying that the Peter Parker we’ve known for years was really a clone of the real Peter Parker who’d actually been wandering America with a faulty memory since the 1970s! Oh wait…they did that once already. It didn’t stick.

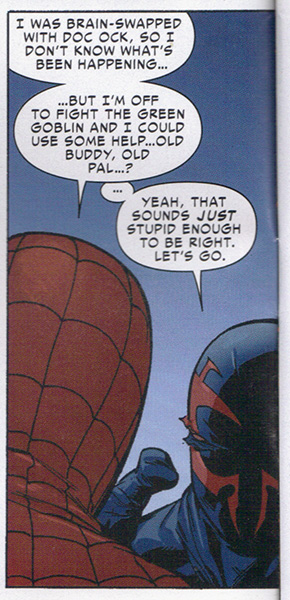

Of course, this didn’t stick either, and comics fans should have known better. In the penultimate issue of Superior Spider-Man, Peter Parker’s consciousness regains control of his body, and he saves the day. Soon after volume 3 of Amazing Spider-Man began with what I assume will be a long story about putting to right everything Octavius did wrong. I don’t know, I have basically dropped the Spider-Man titles for now…perhaps in the future there will be another iteration I’ll be interested in. But here’s the thing, a returned “real” Peter Parker/Spider-Man will still be responsible for whatever ills caused by Doc Ock assuming his identity, just as he is still responsible for everything done by previous versions of Peter Parker/Spider-Man who made poor choices because of the thread of shared identity, regardless of what changes to the character have been made, undone or forgotten.

If there is one thing we can count on in mainstream superhero comics it is the strange tension between the accretion of change and the status quo. That is, while the status quo tends to draw characters back towards it, undoing the events of intervening issues, the changes back and forth and the inconsistencies they engender become part of that on-going story. Even when writers and editors don’t explicitly bring them up within the narrative as they are happening, chances are some creative team down the line is going to pick out that rupture as a way to develop a rehabilitative narrative and turn the story back in on itself. Honestly, I never know if I should love or hate this kind of thing in serialized superhero comics. It seems awfully insular, but at the same time some really fun stories and creative thinking through attention to detail have come out that way. I guess, the most accurate answer is that sometimes I love it and sometimes I hate it, depending on how well it is written. I love the mid-80s revelation that Mary Jane knew Peter Parker was Spider-Man all along, and the related account of her abusive and poverty-stricken family that belied her party girl attitude. But I hated the early 2000s recasting of Gwen Stacy’s time in Europe before her death as a time when she secretly gave birth to Norman Osborne’s rapidly maturing Green Goblin offspring.

Superior Spider-Man is the latest iteration of this cycle. It is just that by appearing to remove Peter Parker altogether, ending a 50 year-long series and starting a new title, the change seems all the more extreme and hostile to fans that abhor change and uncritically embrace their facile notions of tradition. However, Dan Slott seems to have been attempting to accomplish something interesting with the character of Peter Parker/Spider-Man with this series. By temporarily removing him, Slott provides a narrative space for a rehabilitation of a Spider-Man character that despite his self-righteous pretensions regarding power and responsibility has a long history of both abusing power and being something of an impulsive jerk. Furthermore, the inconsistency of how characters are written over the decades means that there are extreme cases where Peter Parker/Spider-Man has been particularly self-centered, immoral or brutal. For example, there’s the 90s story where Peter struck his then pregnant wife Mary Jane (Spectacular Spider-Man #226). Or the 60s comic where he refused the Human Torch’s help with the Sinister Six (Amazing Spider-Man Annual #1), despite his aunt and girlfriend being in danger. Or, in the 80s, when he brutally beat up Doc Ock and tore his mechanical limbs from his body in Peter Parker the Spectacular Spider-Man #75.

Even Slott has contributed to this when he had Spider-Man condone and participate in Guantanamo-style torture of Sandman for information during the “Ends of the Earth” story-arc. Peter didn’t even bother with the usual moral-wrestling afterwards.

Slott attempts a potential rehabilitation of Spider-Man not by trying to put the genie back in the bottle and writing a Spider-Man that annoyingly clings to a classic and pollyanna notion of his morality, but by going in the other direction. He gives us a Spider-Man who adopts the dubious code of the contemporary superhero, who does the things that so many fans want their “heroes” to do and gives us the piling consequences to such an approach. In other words, the Superior Spider-Man blurs the line between the behaviors of heroes and villains in the superhero genre by muddying the very identity of the hero within the narrative itself, rather than by creating a new character (like Spawn) or a parody of an existing character that exists in a separate narrative space (like Lobo was supposed to be to Wolverine). In the course of 30 issues, the Superior Spider-Man kills two different super-villains (shooting one in the head!), viciously beats three others (two of whom are harmless, jokey type foes), blackmails J. Jonah Jameson (currently acting mayor of the city of New York) in order to get a property for his own secret headquarters (Spider-Island), hires groups of armed minions, sets up his own network of surveillance cameras and spider-bots all over the city, and never considers the rapey implications of being with women under an assumed identity.

He charges head first into the criminal status quo, using the language of “finally doing” what other superheroes, like Spider-Man, never have the guts to do. He destroys “Shadowland,” Kingpin’s ninja-filled headquarters and reveals the current incarnation of the Hobgoblin’s secret identity the first chance he gets. Basically, he acts decisively, aggressively and without a thought to the consequences. He is always sure that what he is doing is right, and if not unambiguously and morally right, then at the very least justified. When Mary Jane Watson’s nightclub catches fire, rather than swing over there to save her no matter what, like Peter Parker would do, Octo-Parker merely alerts the fire and rescue authorities and chooses to take out Tombstone and his toughs instead. Mary Jane is surprised when her confidence in her hero’s arrival ends up being misplaced. Octo-Parker doesn’t care about her feelings, he only cares that he did the rational thing. Most versions of Parker would have agonized over the choice.

I am of the school of thought that what makes the Amazing Spider-Man work as a comic book is not Spider-Man himself, (or at least not just Spider-Man), but Peter Parker—both in terms of his relationship to his alter-ego and his various social relations with his large supporting cast. The Superior Spider-Man for the most part eschews his social obligations for his own ambition. Sure he is able to maintain a better relationship with his Aunt May (a point made creepy by Otto’s romance with May once upon a time) and a romance with fellow scientist Anna Marie Marconi (my favorite new character from the series), but only because he is also willing to ignore what he deems as “petty crime,” unconcerned with the potential personal costs of those crimes as the real Peter Parker learned to be upon the death of his uncle.

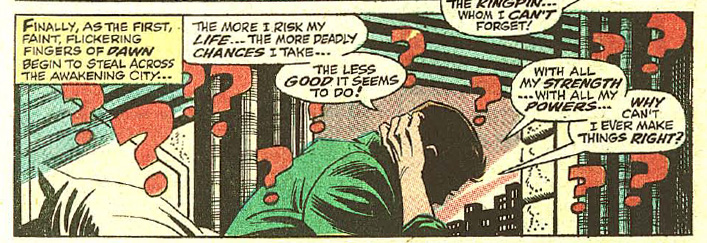

It seems to me that Superior Spider-Man is a kind of answer to a particular kind of fanboy complaint about Peter Parker’s frequent whining and self-doubt. At its heart, Spider-Man comics have been best when they successfully mix a kind of high-flying urban adventure story with characters deeply enmeshed in a setting rife with contingencies. In other words, “With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility” is not about doing “the right thing,” it is really about there being no right thing. There are no good choices. There is only taking responsibility for the outcome of your choices. If anything, Peter Parker as sad sack who occasionally snaps at the people around him and takes on the guise of a happy-go-lucky nut in a bright blue and red costume making with the snappy patter as a form of catharsis (and cathexis), shows us an attitude to the world that is more real (and subsequently paralyzing) than our own often is. The various tales of Spider-Man highlight the complex (forgive me) web of human interaction. It is like a four-color version of Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men. The more you can do the worse the possible outcomes for doing it.

To put it as succinctly as I can, the story of Spider-Man’s origin begins with his sense of responsibility for his inaction—not doing something, not stopping that thief led to the death of his Uncle Ben. Thus he decides to make his life one of action. As the 60s cartoon theme-song says, “wealth and fame he’s ignored / action is his reward.” However, moving beyond that origin point, taken broadly, the Spider-Man narrative seems to be actually about the equal dangers of taking action. Everything Spider-Man chooses to do has consequences, some foreseeable and others not so much, and all of them, even when he succeeds, are to some degree bad. This is especially true when he acts impulsively, like in Amazing Spider-Man #70, when he decides to stand up for himself and put a scare in J. Jonah Jameson, but then realizes he may have given the man a heart attack!

It becomes clear, looking over the arc of Amazing Spider-Man with the 31-issue run of Superior Spider-Man as a kind of coda, that “With great power, comes great responsibility” is not referring to the responsibility to do good that comes with great power—it is everyone’s responsibility to try to do good—but that the consequences of acting have a greater reach the greater your power. Even one of Spider-Man’s most classic scenes reinforces this idea—when saving his girlfriend from a plummet off the George Washington Bridge, the snap of her head when caught by his web breaks her neck and kills her. The tragedy is compounded for the reader by Spidey’s self-congratulatory monologue upon catching her and as he pulls her back up. It may not be Spider-Man’s fault that Gwen dies, but it falls in the realm of his responsibility. In the epilogue story aptly named “Actions Have Consequences,” in the final issue of Superior Spider-Man (this one written by Christos Gage), Mary Jane and Carlie Cooper (another of Parker’s exes) even discuss Gwen’s death in the context of Peter’s responsibility and their own safety. As Mary Jane succinctly puts it when Carlie confirms that Peter was taken over by Doc Ock: “Explains a lot. Doesn’t change anything.”

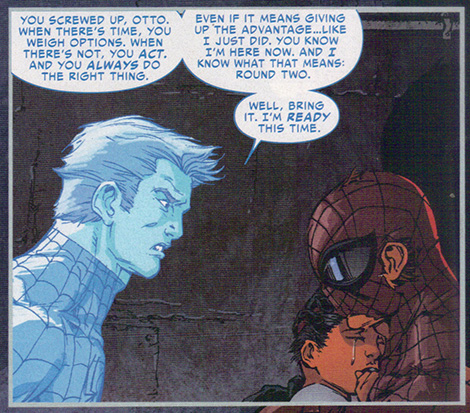

Unfortunately, like most things superhero comics, because of that tension between constant change and adherence to an always returning status quo, whatever promise Slott’s Superior Spider-Man run may have had to explore this idea of responsibility as a core aspect of the Spider-Man character collapses by series end. Unable to deal with the multiple moral quandaries set up by the Green Goblin, Octavius makes the noble sacrifice. He erases his own memory and consciousness from Peter Parker’s body, allowing Parker’s psyche to take over again. In that moment the story becomes not about responsibility, but about some essential Peter Parker-ness that makes him best suited for the job. Boring. In fact, it is worse than boring: the manifestation of Parker’s spirit or psyche or whatever (don’t ask me how it is supposed to work) makes a defining statement that actually makes his perspective indistinguishable from Octo-Parker’s. He says, “When there’s time, you weigh the options. When there’s not, you act. And you always do the right thing.” But isn’t that basically what the Superior Spider-Man has been doing for the 30 issues before this confrontation, because he was sure that his every choice was right?

It certainly doesn’t help that the moment of the “real” Parker’s triumphant return is marred by Giuseppe Camuncoli’s lackluster art and his seeming inability to draw a recognizable Peter Parker. He has a tendency to draw faces like characters are in the middle of an aneurism after straining too hard on the toilet.

Ultimately, what interests me about Superior Spider-Man is its existence as a self-contained example of the flexibility of identity made possible by serialized narratives. There is an incredible torsion of serialized comic book characters, a slow (and sometimes fast) twisting of a character’s identity until editorial has no choice but to declare that the character was a Skrull or a space phantom all along. Much like he did with his run on She-Hulk (though more subtly), Dan Slott plays with this meta-knowledge, by having Spider-Man’s Avenger cohort check him for those possibilities. But the possibility they can never check for without mimicking She-Hulk’s addressing of the fourth wall, or being written into the self-reflexive comic world that Alan Moore created when he took on Supreme, is that this strange-acting version of Spider-Man is the result of 50 years of changeless change.

Or perhaps, it might be more accurate to adopt Paul Gilroy’s notion of “the changing same” to the discussion of serialized comic book identity. Rather than look for an authentic identity as emerging from a relation to some originary moment or particular period of time (like the Silver Age or the Ditko era), we should see it as a developing diverse set of possibilities bound together at any given point by a shared set of collected signifiers that have come together to represent the character. As such, at any period of time the same set of signifiers may not all be present, or have made room for newer ones or to rehabilitate ones previously abandoned.

While the crisis in Superior Spider-Man revolves around the changes evident to those close to Peter Parker/Spider-Man, to the public at large, Spider-Man has not really changed. He is an unpredictable enigma upon which preconceived notions can be projected. Sure, some of Parker/Spidey’s relatives, peers and other companions can tell something is off about him, but the Spider-Man identity remains mostly unchanged in that whatever bizarre behavior he may be exhibiting must be seen in context of a figure that once leapt around the city in an iron spider suit, or a black costume, or a black costume with a slavering maw, or with two extra sets of arms, or drove around in a Spider-Mobile, or…or…or… In other words, he remains a colorful figure that is always changing—compelling but potentially dangerous.

I have not read every Spider-Man comic ever published, but I’ve read enough to appreciate that Slott’s Superior Spider-Man distilled a particular essence of the character that at least feels like a thread that existed throughout the character’s history. There are other elements of the character that have been emphasized over the years—his “spiderness” in Stracyzki’s strained and mostly ignored “The Other” storyline, his employment at the Daily Bugle, his relationships with women, his totemic rogue’s gallery, his run-ins and misunderstandings with the law. But his struggle over the range and depth of his responsibility to others has basically always been there. In removing it as an obstacle to being Spider-Man, Slott manages to put it back in focus as essential to making 50 years of continuity cohere.

[This piece has been cross-posted on The Middle Spaces]

This may be my favorite of your pieces on continuity, Osvaldo. I really like the idea of seeing Spider-Man as a borderline psychotic whacko with multiple-personality disorder.

Has there been a parody that embraces this kind of continuity insanity — the fact that the characters are all completely internally inconsistent, and would basically be extremely dangerous and frightening as a result in the “real world”? I guess you might see Crazy Jane in Doom Patrol as a nod to that…but most of the superhero parodies seem to follow Watchmen in approaching superheroes through individual psychology/Freudianism rather than through the nuttiness of continuity (maybe Ambush Bug gets at it a little too….)

You make this sound pretty appealing as something to read…though probably I’d be happier just rereading the essay again….

Glad you liked the essay, and I think you are right to trust your instinct and avoid this run. . . Having just re-read it in order to write this, I can’t say I liked it all that much, I just liked it more than I remembered and found some interesting promise in it – but still, it is not as good as Slott’s She-Hulk run or his current Silver Surfer run (though it may be too early to tell on the latter). . . I think he does better when not fettered by writing a Marvel “flagship” title. . . that is, I think he may have been freer to write a more interesting exploration of Octo-Parker if had not been writing THE ONLY Spider-Man title of that time, upon which Marvel relies to maintain their brand. I find his writing a lot more playful when he the expectations are lower.

That’s true of Grant Morrison too. The flagship titles are death.

Morrison does play with the idea of endlessly iterated continuity in a lot of his titles…but it’s always more about myth than about seeing the multiplicity as broken or morally bankrupt….

Yup, I agree with Noah. This is a superior piece on Spider-Man. You almost make Peter Parker out to be a kind of Kantian (and Octo-Spidey the reverse I suppose). I know better than to read the actual comic of course. I’m also grateful for the update on Peter Parker’s possession and “divorce.”

Why is Peter Parker a Kantian here? Explain for the slow to catch up?

It could simply have been a case of my reading too fast but it was this section and where this line of thought leads to:

“In other words, “With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility” is not about doing “the right thing,” it is really about there being no right thing. There are no good choices. There is only taking responsibility for the outcome of your choices.”

If there are really no good/pure choices, then there’s only a good will (the only thing “good without qualification” etc. etc….?). So it’s not exactly Kant’s Groundwork but, you know, it’s a Spider-Man comic. Octo-Spidey seems more like a Utilitarian but I haven’t read the comics!

Huh; okay. I hadn’t thought of Kant that way before I guess….

Ha — well, as Suat said, Spidey’s a pseudo-Kantian at best. Kant thinks there are good choices — they’re the ones made in accord with a maxim such that you could will it to be a universal law…but Spider-Man couldn’t actually believe the only (valuable?) thing is to take responsibility for the outcome of your choices. Dr Doom and Fin Fang Foom can do that, too.

Anyway, we all know the real basis for Spider-Man’s morality — A=A…

Re: Peter Parker as sad sack in the guise of a happy-go-lucky nut

I only have a pretty superficial knowledge of philosophy, but this definition of Spider-Man reminded me a lot of Camus’ “Happy Sisyphus”. Since Sisyphus defied the gods by tricking death and escaping the underworld, he had to be punished for all eternity with a pointless task, just like Peter Parker would be punished with the duties of being Spider-Man for letting his innocent uncle die (quite the reverse of Sisyphus’ crime).

According to Camus’ interpretation of the myth, Sisyphus is an example of man “revolting” against the “absurdity” of existence and I think that’s how I would read Spider-Man as well. Peter Parker knows he can never bring his uncle back, still he’s laughing at all the evil-doers he has to face, mocking them. “There is no fate that can not be surmounted by scorn” writes Camus. “One must imagine Sisyphus as happy.”

So I would guess Spider-Man is actually the opposite of (or at least a response to) the traditional “Kantian” superhero (Superman, Captain America) that still believes in a greater good, right choices, universal law, unaware of the absurdity of human existence. I also think these superheroes are much more “A=A” than Spider-Man, I actually wonder if Ditko’s objectivism ever really influenced the character? It’s been a while since I read the Ditko run, but the way I remember it, Spidey always pretty much was the opposite of a preaching Objectivist?

The two sides of Kant that have appeared above — the absolute moral quality of a the good will, on the one hand, and a belief in categorically good actions, on the other — meet in the concept of *duty*. A good action is one that emerges from a sense of duty to the Moral Law — neither the good qualities of one’s character and inclinations (say, Superman) nor the instrumental goodness of the acts and the way they create a better place (maybe, Batman?).

Ironically, then, the Kantian hero would be someone who feels no personal inclination to follow the Moral Law or do the right thing (e.g., empathy, paternalism, the drive to protect others). It does not come naturally to him. Instead, he does so anyway out of an allegiance to a rational, universal moral maxim. In its most extreme form (one that Kant probably wouldn’t much like), it might be close to that existential vision posited above: I hate the Law — My Law — but I am bound by my Will and Reason to follow it anyway.

That sounds a bit Spidey-like. After all, what hero threw away and willfully picked up his mantle more frequently (and more literally) than he?

“Has there been a parody that embraces this kind of continuity insanity — the fact that the characters are all completely internally inconsistent, and would basically be extremely dangerous and frightening as a result in the “real world”?

Not exactly a parody, but in Avengers Disassembled: Brian Michael Bendis reveals that Scarlet Witch is basically completely insane, and has been mentally ill for a long time. As evidence of this, he has a montage of the Scarlet Witch being inconsistent in old comics. It’s maybe sort of the thing you are talking about, here’s the montage:

http://goodcomics.comicbookresources.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/transia2.jpg

Regarding Objectivism and Spider-Man–Blake Bell’s Ditko biography points out that in one of Ditko’s last Spider-Man issues, Peter Parker bitches about all the annoying protestors on his campus, which was probably Ditko’s contribution. Apart than that, though, Peter Parker doesn’t seem very Randian. In one of Ditko’s recent comics/Rand tracts, he chastises Lee both for advocating the superhero-with-problems schtick and for hogging the credit for Spider-Man, which seems slightly contradictory to me.

Peter Bagge based The Megalomaniacal Spider-Man on his view that Spider-Man’s character is a cross between Lee and Ditko. Over the course of the story, Peter goes from being a neurotic superhero to a power-hungry CEO to a Rand-obsessed crank.

I think I once heard Rand call Kant the most evil thinker of the modern era, far worse even Karl Marx.

Osvaldo, I assume you’ve read Ben Saunders’ _Do The Gods Wear Capes?_(?) He talks about the whole Gwen Stacy storyline (including death, reader-response, clone/revival, reboot as pregnant with Osborne, etc.) in similar ways. The chapter also discusses the ethical implications of Spider-Man and his many mistakes. It also talks about “repercussions” of Spidey’s actions and the impossibility of correct choices for Spidey. In other words, many of the beats you touch on here (only without the attention to Octo-Spidey).

I have not read it, or even heard of it. I am looking it up now.

Yeah, I was kidding about Objectivism in Spider-Man…although, come to think of it, arch-enemy JJJ seems like a Randian villain, fuelled by ressentiment. (Then again, everything I know about Rand, I learned from Nietzsche, so…)

Ultimately, what concerns me about Spider-Man are not his ethics, so much how a narrative of identity is constructed through a selective (re)collecting of his various experiences, memories, actions in order to act as if he is actually abiding by an ethical framework.

“I think I once heard Rand call Kant the most evil thinker of the modern era, far worse even Karl Marx.”

I didn’t know that but the web says:

“You may also find it hard to believe that anyone could advocate the things Kant is advocating. If you doubt it, I suggest that you look up the references given and read the original works. Do not seek to escape the subject by thinking: “Oh, Kant didn’t mean it!” He did. . . .Kant is the most evil man in mankind’s history.” Ayn Rand

“As to Kant’s version of morality, it was appropriate to the kind of zombies that would inhabit that kind of [Kantian] universe: it consisted of total, abject selflessness. An action is moral, said Kant, only if one has no desire to perform it, but performs it out of a sense of duty and derives no benefit from it of any sort, neither material nor spiritual; a benefit destroys the moral value of an action. (Thus, if one has no desire to be evil, one cannot be good; if one has, one can.)…Those who accept any part of Kant’s philosophy—metaphysical, epistemological or moral—deserve it.” Leonard Peikoff

See, I still really like Kant. Pleasure is bad — like, not sexual pleasure any more than anything else, but just actually enjoyment. It’s so anti-capitalist. No wonder Rand didn’t like it.

Jack – Funny, there actually is a whole page of student protesters pestering Peter Parker in the very last Ditko issue of Spider-Man, and it’s all typical Ditko polemics. My reprint also includes the corresponding letters page, and when a student complained about the unfair portrayal of the protesters, Stan Lee (or whoever answered these) wrote: “We never in a million years thought anyone was gonna take our silly protest-marchers sequence seriously! We just tossed it in for a little comedy relief – or so we thought!”

Osvaldo, sorry, I know these aren’t the points your essay was raising at all. Anyway thanks for another interesting piece. Makes me feel kind of bad I can hardly ever bring myself to read any new superhero comics anymore. All I’m waiting for is the third and final installment of Seaguy :)

I’m no great Kantian scholar, but this sounds like a misreading of Kant to me. (Shocking that a Randian — I mean Peikoff — would misunderstand philosophers, right?)

AFAIK, Kant doesn’t think pleasure or happiness bad. He merely thinks that acting because of them is not acting rightly — to act rightly, you must act because of your assent to the laws of pure reason or whatever the hell. You do the right thing because you know that it is your duty to do so. But you’re allowed to enjoy doing your duty too, if you want — you don’t get any extra brownie points for not enjoying it. Kant’s is not purely an ethics of masochism, at least based on what I’ve read…

Again, it’s been a long time…but I feel like there’s pleasure and there’s pleasure in Kant? Sensual, transient enjoyment is the thing you aren’t supposed to pay attention to (no impulse buys!) Instead, following the moral law is the richer joy of being your true noumenal self, which is the self that knows (and in some sense in Kant actually is) God.

Kant’s quite Christian, so an ethics of masochism isn’t exactly that far off the mark…

Spider-Man is a hero who seems largely motivated by duty, so he makes sense as a Kantian in that sense, maybe. Osvaldo’s point about his shifting identity though is very un-Kantian; Kant’s very much about a stable identity providing the basis of a stable morality; the true self is the moral law, which doesn’t change.

Spidey’s wise-cracking is also inconsistent, right? Peter Parker is not a happy go lucky guy, but he puts on the Spidey suit and suddenly he’s the class clown. That’s right from the start…and seems to be more about Ditko writing the plot and Stan Lee writing the text bubbles than about any sort of actual psychological character development. There were multiple creators from the get go; Spidey was always cracked.

Anyone have an issue # for student protest scene? I have heard people talk about it before and always thought they were talking about issues #68 and #69 (which features a story clearly modeled after the Columbia University student takeover of buildings – but that can’t be it since Ditko left after #38.

Osvaldo, I just wanted to chime in and say– what a good piece! And you’ve broken away at my resolve to stop reading superhero comics… over a few articles, you’ve definitely made a case for Slott.

Pop-culture story-universes might be the most fascinating and convoluted narrative systems people ever created. I love the work you’re doing about them, and it makes me want to jump in and talk about them too.

Thanks for the kind words Kailyn, but now I feel responsible for your return to superhero comics! Kailyn would have continued to be taken seriously if I had just never written about superheroes in a compelling manner! What hath I wrought? ;)

Oh, and for those who are curious, there are captions/comments/sources for the images included here on the version of this found on my blog (link above) – it is just that the format of captions here at HU make them difficult to scan well in the text, so I just don’t include them.

Hey Osvaldo, it’s page 10 of # 38, Ditko’s very last issue. You can see a few panels here: http://www.supermegamonkey.net/chronocomic/entries/amazing_spiderman_38.shtml

I talk more about Spidey and Kant over here.

Boy, it’s been a long time since I visited this site.

” But here’s the thing, a returned “real” Peter Parker/Spider-Man will still be responsible for whatever ills caused by Doc Ock assuming his identity, just as he is still responsible for everything done by previous versions of Peter Parker/Spider-Man who made poor choices because of the thread of shared identity, regardless of what changes to the character have been made, undone or forgotten.”

In what sense? How can he be responsible for something he didn’t do and never wanted to do?

“It is just that by appearing to remove Peter Parker altogether, ending a 50 year-long series and starting a new title, the change seems all the more extreme and hostile to fans that abhor change and uncritically embrace their facile notions of tradition.”

Weren’t people critisizing it the same people who disliked the 2007 soft-reboot precisely for removing lots of popular changes to the status quo? Peter/MJ marriage, Harry Osborn’s death, Norman Osborn and Aunt May knowing his identity, Peter/Black Cat relationship ect.

Comon reasons I’ve seen people were against the change was that the idea was seen as cliche, unworkable and because of Doc Ock trying to sleep with MJ-ergo, raping her, was deemed distasteful.

“Furthermore, the inconsistency of how characters are written over the decades means that there are extreme cases where Peter Parker/Spider-Man has been particularly self-centered, immoral or brutal. For example, there’s the 90s story where Peter struck his then pregnant wife Mary Jane (Spectacular Spider-Man #226). Or the 60s comic where he refused the Human Torch’s help with the Sinister Six (Amazing Spider-Man Annual #1), despite his aunt and girlfriend being in danger. Or, in the 80s, when he brutally beat up Doc Ock and tore his mechanical limbs from his body in Peter Parker the Spectacular Spider-Man #75.”

The fact that Peter has been written like a complete asshole at times in undeniable, but I don’t think any of your examples are particularly good.

The first one was an accident that happened when he had serious mental breakdon and was an accident.

Second one, really, that was just a genre convention-Marvel superheroes treated each other like shit during Silver Age (Peter unlike them even has an excuse of being 16) and Lee wanted to advertise FF. I think it would be more fair to use something from 70’s.

I haven’t actually read that story, but didn’t happen right after Ock almost killed Black Cat? Spider-Man getting needlessly angry at supervillains is actually rather consistent character flaw, not an inconsistency. Besides, why is he NOT supposed to tear of his arms? I mean, they aren’t part of his body, he doesn’t feel pain from it. It’s actually less stupid than how in other comics, they just put it in someone’s basement and wait till Ock takes it back.

“never considers the rapey implications of being with women under an assumed identity”

See, that would be a good point, if the story and Slott himself considered those implications. As it is, his attempted rape of MJ is treated as wacky comedic hijinks and are entirely about PETER and how it hurts HIM. And Ock’s romance with Anna Maria is treated as a redeeming, humanising trait.

“In other words, “With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility” is not about doing “the right thing,” it is really about there being no right thing. There are no good choices. There is only taking responsibility for the outcome of your choices.”

It’s both. I see no real contradiction in stories saying “you need do the right thing (using your abilities to help others)” and “you should take responsibility for screwing up”.

And the phrase is first used at the end of the origin, meaning that the moral has already been told by the end.

“Everything Spider-Man chooses to do has consequences, some foreseeable and others not so much, and all of them, even when he succeeds, are to some degree bad.”

Not really. Even if argue that stopping a supervillain from robbing a bank is bad to a degree, since it means he’ll be angry and go after him (which, since he can easily defeat him anyway, seem like reaching to me), some of Spider-Man’s actions have completely positive outcome. Those who don’t are usually about HIM being unhappy, which is just part of the “doing the right thing”. You are supposed to do it, even when it’s hard.

Also, a lot of those comics are written from Peter’s perspective and sometimes what he thinks isn’t what the reader is supposed to think-just because he believes he is responsible for something, doesn’t mean he is, as the stories pointed out numerous times he suffers from guilt complex.

In that moment the story becomes not about responsibility, but about some essential Peter Parker-ness that makes him best suited for the job. Boring.”

The thing is-that’s what it was always about. Ever since the beginning, it was meant to be a traditional “why heroes are better than anti-heroes” story. I’m afraid any depth you’ve read into this beyond that is simply seeing things that were never there to begin with.

Besides, I’m not sure what is your proposed alternative? You mention adherance to the status quo, so… You think Octopus should remain Spider-Man?

“While the crisis in Superior Spider-Man revolves around the changes evident to those close to Peter Parker/Spider-Man, to the public at large, Spider-Man has not really changed. He is an unpredictable enigma upon which preconceived notions can be projected.”

I’m not a Spider-Man expert, but I really don’t think so. As far as long-running charaters go, Peter really isn’t all that inconsistent. He may be put in different situations and react differently, but that’s not really him suddenly acting like a different person. It’s why so many people complain about his potrayal post 2007.

As far as I’m concerned, whatever deep themes was Superior trying to have, it was killed by ridiculous laps in logic and bad characterizations and just poor writing period. That scene in a back-up for Superior #31 is honestly one of the most nonsesical break-ups I have ever read.

I don’t know how consistent Peter is over time. Honestly, his character doesn’t exactly ever make sense to begin with. At the outset, he’s a bitter, shy, bullied teen who takes up superheroing out of trauma and guilt—and then he puts on the mask and he becomes this wisecracking jokester. Not only is that incongruous, but it’s never really explained or discussed.

The probable reason of course is that Ditko is the one who gave Peter the guilt and trauma, and Stan Lee writes the wisecracks, and never the twain shall have a story conference. But if you try to make sense of it in-story, it doesn’t really work.

I don’t know, Noah… Given what we know now from comment threads everywhere, it seems like the combination of anonymity and publicness that comes with the Spider-Man identity could transform a sullen, put-upon outcast into an antagonistic wisecracker.

Hah; touché.

You’d think someone somewhere would comment on that right? Or that Peter himself would? It’s not just the contrast, but the sense that no one seems to have figured out that there’s a contrast. Peter always talks about his dual identity as a burden; he doesn’t talk about how anonymity is liberating…

>In what sense? How can he be responsible for something he didn’t do and never wanted to do?

I think I explained it at length in this piece. There is a thread of shared identity – “Spider-Man” – that Parker participates in and is responsible by the very fact of having that power. Part of the responsibility of that power and identity is being accountable for it. This applies in two ways 1) as I said above in terms of being “Spider-Man” – an identity people see around the city and in stories that has no room nuance in terms of being a public figure, and 2) in terms of being the one who decided to use these powers and resultant identity in the way he does.

From a meta-perspective, Peter Parker can’s say well, Roger Stern wrote me to act like X, but now Dan Slott writes me to act like Y so I am not responsible for X, or Y doesn’t count. Rather we are meant to try to make the incongruity cohere.