20 years ago, by the end of July, the genocide in Rwanda had ground slowly to a halt as the Rwandan Patriotic Front took control of all but a small margin of the country. I was only 12 years old, but had followed the news coming out of the tiny east African country with an interest bordering on obsession. The images were appalling: row after row of hastily constructed huts and tents, children not much older than me carrying water down dusty roads for miles, a rail-thin mother nursing her baby among piles of cloth. The piles of cloth resolved into human-shaped forms, but they didn’t move. These stood in stark contrast to the bright floral dresses and poufy hair of Christine Shelley, the Clinton administration’s State Department Spokesman, as she awkwardly avoided the “g-word.” Video crews passed through filthy camps, and on occasion, the news anchor warned viewers of upcoming “graphic footage,” usually a wide keloid scar, sometimes spread across a handsome young man’s cheek. It wasn’t until years later that I realized how ambivalent these images were: reporters had largely been dispatched to refugee camps in bordering Uganda and Zaire, where survivors were forced to live alongside those who had tried to kill them.

My experience of horror and pained sympathy was retrospectively unmoored from my ethical stance. I had no idea for whom I had felt, which felt very ominous. This prompted a more critical eye: “Who is being shown here? Where is their suffering coming from? To what end?” It also provoked suspicion of my emotions: “Who am I feeling for? And what is the point of feeling anyways?”

During my graduate program, I was reminded of the source of these questions during two key events. I was invited by my advisor and mentor Gary Weissman to TA a Literature of the Holocaust class, and rather than giving me the job most TAs are tasked with (grading mounds of papers), he insisted I co-teach the course. It was an honor I didn’t take lightly, and I spent weeks researching, trying to better understand how to frame debates about the representation of the Holocaust in an advanced classroom. The course went through works like Elie Weisel’s Night and Primo Levi’s Survival in Auschwitz, as well as Art Spieglman’s Maus. By the time we hit Maus, both Gary and I were frustrated (and occasionally unnerved) by some of the responses from students. As we plowed through midterm papers, we kept coming across a phrase again and again: “walking a mile in their shoes.” I’ll return to that in a moment.

The other key event, not long after TAing for Gary, was when the man who would become my husband handed me J.P. Stassen’s Deogratias: A Tale of Rwanda, a fictional graphic novel following the title character through his lives in the pre- and post-genocide landscapes. In the era before the genocide, he is depicted as a normal young man: going to school, working, getting drunk, and attempting to woo two sisters. In the era afterward, he resembles the images of the refugees I had seen so many years before: torn, dirty shirt, dull, haunted eyes, slouching towards the hope of a bender. His search for urwagwa, a banana beer, is relentless, and only 26 pages into this 79 page work, Deogratias is rendered bestial, becoming a dog as he creeps on all fours through the landscape back to an open tin-roofed shack not quite the width of a bed. Moving back and forth between the present and the past with the title character’s memories as a sort of frame, readers are introduced to a small cast of characters. Deogratias is in love with two Tutsi sisters, Apollinaria and Benina, who are the daughters of Venetia, a local woman and sometime-prostitute. Apollinaria is the product of Venetia’s affair with Father Prior, a Catholic missionary, who is a mentor to Brother Philip. Brother Philip is new to Rwanda, and earnest in his desire to help. The French Sergeant is a more cynical character, as is Julius, an Interahamwe leader (the Interahamwe were the Hutu youth militias responsible for the bulk of killing during the genocide). More minor characters include Augustine, a man of the Twa ethnic group, and Bosco, a Rwandan Patriotic Front officer who has become a drunk after his work to help stop the genocide. Much of the graphic novel is devoted to “slices of life,” brief moments and short conversations that would be casual in any other context.

The Rwandan Genocide took place over 100 days in 1994, starting in April the day after a plane carrying President Habyarimana was shot down. While there was a plan in place in the government to slaughter all Tutsis, this was not a “top-down” genocide. As Mahmoud Mamdani discusses in When Victims Become Killers, the Rwandan Genocide was distinct from the Holocaust in part because a large proportion of the population took part in the killing. Between 600,000 and a million Tutsis were killed by a minimum of 200,000 genocidaires in a country of 11 million. While the differences are significant, it is also worth remarking on the similarities. The Rwandan Genocide was as “efficient” as the Holocaust. Unlike Western media representations of the violence, this was not “Africa as usual”. It was a tragedy that was the combined result of decades of colonial rule, Western reluctance to intervene in an area with few natural resources, racial enmities manipulated through the use of propaganda, French support of the genocidal government, a toothless U.N. Peacekeeping force, and many, many other factors.

Deogratias is not the first graphic novel to explore genocide, and certainly is not the most famous. That honor goes to Spiegelman’s landmark Maus, which explored his father’s experiences during the Holocaust and Spiegelman’s own difficulty with both his father and recounting his story. His visual conceit in this work employed a variety of animals (Jews as mice, Germans as cats, etc.) to highlight the factors of race, ethnicity, and nationality in the genocide. Maus is hyper-self-reflexive, Spiegelman frequently weaving scenes of his arguments with his father in the present day among illustrations of his father’s recollections. It is a powerful work interrogating racism, memory, intergenerational relationships, the effects of historical trauma on a family, and what it means to tell a story. As such, it is very “talky”—Spiegelman litters the page with questions and anecdotes, deftly balancing the textual and visual elements of the graphic form.

Deogratias, in contrast, is an intensely quiet graphic novel. The title character rarely speaks, and while we see the pre-genocide world partially through his memories, he never contextualizes them, or connects them to the silent, dirty man we see in the post-genocide era. The characters who speak in the pre-genocide era have relatively normal lives and normal concerns. The characters who speak in the post-genocide era carefully avoid any reference to the events of April-July 1994. What I find perhaps most important about Deogratias is the extent to which Stassen emphasizes the unreliability of images and the emotional responses they provoke in readers.

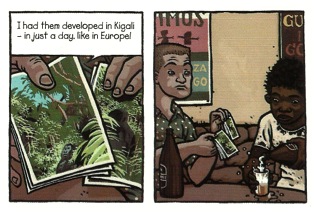

The comic opens with Deogratias staring blankly into an open-air café set in a hotel. A smiling white man hails him, inviting him to sit and drink. The man, later identified as a French sergeant, attempts to show Deogratias pictures from his recent tour of the gorilla preserves in Rwanda (among Rwanda’s only “natural resources”). One panel is entirely filled with these vacation photographs, so readers may assume that we are sharing Deogratias’s point-of-view, but the following panel reveals that in fact he is not looking at the photographs (see Figure 1). He is staring intently at the beer he is pouring into the glass, while the French sergeant looks briefly confused.

Figure 1

At first glance, this would appear to be a relatively minor event in a graphic narrative about genocide, but in fact, it lays out the primary thesis: attempts to “see through the eyes” of those who went through the genocide are always partial, and are limited by the relative privilege of the reader.

This recalls what I found in the Literature of the Holocaust course while struggling to explain to students why “walking a mile in their shoes” was perhaps an inappropriate phrase. While we read novels and memoirs, the imaginative closure students experienced while attempting to envision what was being explained in the text prompted them to fantasize “seeing” the Holocaust. While not the worst use of the imagination—after all, we rely on texts to help us better understand the world—it also underscores an often-overlooked issue: to what extent is it ethical to create metaphors between one’s own experiences and situations of extremity?

Maus, because of its form, offered a corrective against the impulse to closely identify with experiences distant from our own positions of relatively safe U.S. citizens. When one looks at a panel, one is simultaneously invited to see through a window into the world and reminded that what they are seeing is mediated. Students were intensely interested in Maus, but were also able to see the characters’ experiences as distinct from their own lives and emotions.

Deogratias takes the ethical self-reflexivity inherent in the graphic narrative form and uses it to emphasize what the reader generally cannot see from their vantage point in the Global North. The tourism photographs of gorillas are the most common image out of Rwanda aside from those of the genocide, which, as I mentioned above, are often not properly images of Rwanda at all.

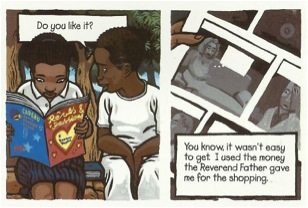

Stassen narrows this distance when depicting the pre-genocide era by showing scenes that could occur anywhere in the world. For example, Deogratias waits for Apollinaria outside of school, eager to present her with a comic book as a present. The large heart on the cover suggests its topic is romance, but when we look at the panels through Apollinaria’s perspective, we see a lonely woman on a couch, as well as the corner of a panel depicting an upset or disappointed man (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

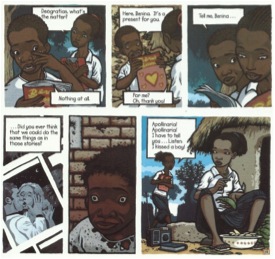

Deogratias asks her “if we could do the same things as in those stories?” at which point, Apollinaria rejects both the gift and the sentiment. The comic, meant to communicate his love for her, reveals the opposite; the page Apollinaria views shows abandonment and frustration. Immediately afterward, Deogratias is approached by Apollinaria’s sister Benina. Deogratias hides his tears, and promptly presents Benina with the same comic book. Unlike Apollinaria, Benina sees a scene of passionate kissing, overlain by the same question Deogratias had posed to her sister, which is more successful in this case (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

As readers, we are prompted to connect with, if not identify with Deogratias. He is the main character, and while his intentions are not always pure, his actions are understandable; he is a teen trying to figure out his way in the world. In addition to the scene’s familiarity—many young men have struggled to woo young women with gifts—it is important to note the ambivalence of the images received by each sister. Neither sees “the whole picture,” wherein the comic depicts both suffering and passion, and only Benina sees the image that Deogratias intends.

In the post-genocide era, however, the reader watches Deogratias as the memories become too strong, and he physically transforms into a dog. The transformation recalls one of the most ominous aspects of post-genocide Rwanda. In Philip Gourevitch’s We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed with Our Families, he recounts that “The nights were eerily quiet in Rwanda. After the birds fell silent, there were hardly even any animal sounds. I couldn’t understand it. Then I noticed the absence of dogs. What kind of country had no dogs?” (147). The RPF had killed them all because the dogs were eating the corpses.

Deogratias’s transformation is symbolically representative of the trauma undergone by the country. In his continued presence, he is a manifestation also of what is absent in the present day. Over the course of the comic, it becomes clear that not all of the characters we saw in the past have survived to today, but it remains unclear how precisely Deogratias escaped their fates. As a sympathetic Hutu who was intimately connected with a Tutsi family, he would have surely been one of the targets for the Interahamwe. Occasional stray references during the course of the comic suggest he may have been complicit, but at those moments, he retreats into happy memories. It is not until Brother Philip returns and sees Deogratias that the reader understands that Deogratias has been systematically poisoning all of those complicit in the genocide, from the French sergeant to Bosco to Julius.

In addition, Deogratias’s role in the genocide is revealed. In a scene from the genocide itself, the Interhamwe are depicted retreating to the Turquoise Zone. Augustine comes looking for Venetia, Apollinaria, and Benina, and Julius crudely describes the sisters’ rape and murder at the hands of Deogratias and others. The reader is left to wonder why he would be the protagonist.

Herein lies two major aspects of why Deogratias is an essential work. In the first place, it emphasizes how point-of-view in graphic narratives can provide important insights for what it is to “empathize” with images. As readers, we exist in a privileged space in relation to these characters: a space of safety wherein we can choose not to look. Furthermore, what we are shown when we choose to look is suspect as well, because what we see may be only partial. We may misinterpret it. Both the provisional nature of images and the chance of misinterpretation suggest that images can lead us to dangerous conclusions. In the case of the Rwandan Genocide, we conflated perpetrators with victims. We misrecognized the violence as something “naturally African,” something that happens in those places.

The second aspect Deogratias expertly negotiates is the extent to which the reader is allotted access to victim experience, and what victim experiences can be emotionally legible. By invoking empathetic identification with a perpetrator, to some extent Stassen is suggesting a broader complicity in the genocide than simply those hundreds of thousands that did the killing. At the end of the graphic novel, we see through Deogratias’s eyes as the bodies of Benina and Apollinaria are eaten by dogs (see Figure 4). In this moment, we are both visually identified with the culprit and are shown an image from the genocide itself—one considerably more extreme than we saw during those months in 1994.

Figure 4

When readers in the Global North seek to “walk a mile in someone’s shoes,” it is perhaps an honest desire to understand experiences of extremity, but we rarely want to recognize where our paths lay in relation to the ones down which we vicariously traipse. Deogratias is a powerful precisely because it exposes us not to the subjective experiences of the victims, but to that of the perpetrator. I am not asserting that victims’ stories are unimportant. I am asserting that Deogratias reminds us that the object of our empathy may not be deserving of it, and that, perhaps more importantly, from our vantage point in relation to the Rwandan Genocide, we were considerably closer to the bystanders who did nothing than to the victims who suffered.

This is only tangentially related to the analysis of the comic above, but taking the broad perspective two decades on from the Rwandan genocide, the siren song of empathy becomes even more troublesome. Especially in the light of the Kagame regime’s intimate involvement in the Second Congo War (the annexation of lands, theft of mineral wealth, his support of M23 etc.) and the resultant death of millions. Certainly empathy for the victims of the genocide prevented earlier censure in this instance. The “heroes” of yesteryear quite often become the villains of the present.

Oh, I’m with you. I didn’t want to go overboard during the post, but the gist of the larger argument I’m making is that empathy is generally confused with this “shoe walking”–real empathy takes mounds of context and intimate knowledge, and even then, is difficult. Even then, it’s not coequal with action, nor is it necessarily positive. Feeling doesn’t equate to alleviating suffering. Torturers are great at empathy–they know exactly how to make you hurt most.

I’m with you on Kagame, and the “heroes.”

My father lived through the German occupation of Paris during the Second World War. He always emphasised to me that it was impossible to predict how individuals would act in such a situation.

People you would have classed as good or even saintly acted horribly. Other people who were seen as worthless assholes became heroic, hiding Jews,joining the Resistance…

Empathy with evil-doers is dangerous but necessary. We can’t just write off people as monsters without recognising the potential for evil within each of us. Empathy, however,must not evolve into sympathy in such cases.

Anyway, excellent piece, Kate.

Thanks! I think the terms are slippery–I’d love to discuss it more. I see sympathy as feeling *for* someone, while empathy as feeling *as that person feels from their unique vantage point.* Just as a clarification of how I’m thinking of the terms, since they’re used in different ways in different circumstances.

Alex, I’d love to hear more about your father’s experiences. Have you ever written on them at any length? I imagine it would be a great meditation.

Great piece on Déogratias, Kate. I think context is important as well. This was perhaps one of the first graphic novels about the genocide and was published in 2000 at the same time as many of the novels from the Rwanda: Ecrire par devoir de mémoire project in which many of the authors also struggled with how to represent the genocide. In this regard, Stassen’s sophisticated narrative and visual approaches are “intensely quiet,” as you put it, and also extremely powerful. Interestingly, while Stassen encourages readers to identify with Déogratias while also problematizing such a process–indeed, the lack of contextualizing information about the genocide in the paratext directs readers’ attention to the narrative–it seems that he was dissatisfied with reactions to the text that mischaracterize it as absolving perpetrators of their participation. Evidence for this manifested in the publication of Pawa: Chroniques des monts de la lune only two years after Déogratias. In contrast to Déogratias, Pawa abounds with contextualizing information. In fact, I would argue that Stassen’s work since 2000, including Déogratias, engages readers in making the genocide and its continuing effects thinkable (to use Mahmood Mamdani’s term).

Similarly, continued discussions about the genocide, calls for action against those responsible continue, and also critiques of the grossly skewed media coverage of the genocide attest to the importance of dialogue and the potentially transformative role representation can play (including, of course, graphic novels). Indeed, the publication of La fantaisie des dieux: Rwanda 1994 by Patrick de Saint-Exupéry and Hippolyte early this year in conjunction with the 20th anniversary of the genocide is but one example.

Thanks, Michelle! A particular thanks for the recommendation of Pawa and La fantaisie des dieux, which I haven’t yet read because I only recently developed reading competency in French. Mamdani’s work has been so vital to my conceptualization of this project, and an interesting corollary is Henry Greenspan, whose work on Holocaust survivor testimony works with some of the same ideas in a different context. Have you read Michael Rothberg’s Multidirectional Memory? It adds an interesting dimension to discussions of decolonization and genocide, which is useful (I think) particularly in the case of Rwanda, which is so frequently compared to the Holocaust (more, I would argue, than any other genocide in the 20h century).

I think that’s one of the interesting things we see in terms of context (and skewed context) in the States–the Holocaust stands as a measuring standard for what suffering “should” look like, which allows us to efface our own genocidal history, as well as our status as bystanders (at minimum) in the case of Rwanda (and others).

When I was initially researching Stassen some years back, I read dozens of reviews that read Deogratias as “absolving perpetrators,” as you mention, and I was shocked. I still can’t quite see how that’s the reading one could come away with, in spite of all of the blanks Stassen leaves. Those blanks always seem more to me like a pregnant pause in an uncomfortable conversation.

Though I’ve yet to look at Greenspan’s work, I agree with you about Rothberg’s notion of multidirectional memory. In fact, I wrote a chapter to be published next spring in Postcolonial Comics: Texts, Events, Identities about Stassen’s short piece “Les visiteurs de Gibraltar” in the French magazine XXI that engages with multidirectional memory. Even though the short BD reportage is about immigration from Africa to Europe, Stassen includes a section on Walter Benjamin’s fateful attempt to cross the border from France to Spain during WWII. The link between the Holocaust and postcolonialism is no accident and I think Stassen’s visual treatment throughout “Les visiteurs de Gibraltar” offers an insightful take on multidirectional memory and the power plays at work in representing the past and its relationship to the present.

Oh, I’ll look forward to reading it! That sounds fantastic! Shoot me an e-mail (my alternate is katepolakmacdonald@gmail.com) when it comes out.

This was an enormously interesting read. Not sure I get your larger argument about empathy, though. Like Alex, I don’t see how empathy is bad, even when you’re identifying with bad guys who “may not be deserving of it.” Seeing some streak of humanity in a monster is not so different than acknowledging the imperfections of a victim. Also, it’s nuts to say torturers are great at empathy. There’s a huge difference between grasping the mechanics of pain and emotionally identifying with a victim, surely.

I’m also confused by your political indictment of readers as bystanders. Seems like you’re conflating government and citizens.

I’m with Kate here, I think, in the sense that I see how empathy can be a really dangerous and bad thing in the right circumstances. Think about the way the Iraq intervention was justified for example; a fair amount of the push to war was leveraging of empathy for Saddam’s victims. That’s kind of true in all wars; I was just reading about how the Nazis used propaganda about Germans being persecuted in the Sudentenland as a way to gin up enthusiasm for invading there. And as Suat said, in Rwanda, empathy for the persecuted Tutsis has ended up erasing the way that, after the genocide, the Tutsis engaged in violence and targeting of the Hutus.

You could go on and on, really. Empathy for the victims of the Holocaust is one of the ways that America has positioned itself as good (we were on the right side there) and so erases our own unpleasant actions (as Kate says) including, for example, our refusal to deal with the way our support for Israel contributes to the persecution of Palestinians. Empathy without knowledge coupled to power can result in a lot of bloodshed.

Yeah, true. I was really talking about the context of art.

That said I don’t think the rhetoric behind the Iraq War leveraged empathy; it leveraged fear. That’s really at the heart of most propaganda, right? Israel’s a better example., though the American public’s perception of that conflict is shaped as much by anti-Arab sentiment as it is by empathy for victims of the Holocaust.

I think it worked on both? That is, there was certainly discussion of how Saddam was dangerous to us…but left support for the war (Christopher Hitchens, Jean Elshtain) largely focused on the need to save those at Saddam’s mercy (the Kurds, dissidents, and especially women.)

Pingback: Comics A.M. | Square Enix halts 'Hi Score Girl' amid copyright claims | Robot 6 @ Comic Book ResourcesRobot 6 @ Comic Book Resources

Kim, thanks for the comments! Noah covered much of our shared position, but a couple other thoughts on the relative dangers of empathy. In terms of the torturer example Elaine Scarry has written about this with depth and verve, and Peter Goldie’s account of human emotions is also worth a look. They explain empathy and its potentially negative ends in detail. For a less heavy, theoretical account, J.D. Trout’s Why Empathy Matters is an interesting (although divergent) discussion of the limits of empathy. He gives a very nice account of cognitive biases, too.

I definitely agree that “seeing a streak of humanity in a monster” is important, something that allows us also to monitor our own consciousness in order to prevent becoming monstrous. But I see that as fundamentally different than empathy, which I think of as doing the very difficult work of truly embodying another’s perspective. I don’t think empathy is common, and certainly not as common as we use the term. I think, more often, what we feel is some form of emotional contagion–where we feel sympathy/pity/etc., but from our own position, and without subjectively adopting another person’s perspective.

With that in mind, the bystander argument is meant to underscore the extent to which readers *have* felt something for the characters, but nonetheless have not taken action commensurate with that emotional connection. This is part of a much longer discussion of the extent to which images of suffering promote emotional–but *not* material–engagement; it’s also part of a much larger discussion over the use of those images, and the extent to which they can be exploitative and manipulative.

I know that sounds a little general, so for example, say there’s a photograph taken of a starving child in a war-torn country (there have been many, of course). That photograph is picked up by an NGO for an awareness-raising campaign, and results in donations. Great! However, on one hand, it may do little to nothing to materially improve the life of its subject, who is objectified as the “face” of that country, while also simultaneously reinscribing sets of expectations the more privileged viewer has about “those” places, even if it simultaneously prompts them to donate money to alleviate that objectified suffering…which they are consuming. Furthermore, the donation itself may also allow the viewer to gloss over other, more important action that *should* be taken (i.e. not supporting x company that ruthlessly exploits the economy of the country, for example).

I see Deogratias as partly critiquing that cycle. It’s not that I’m rejecting images of suffering, or emotional connection, either. But I think these are more problematic than we usually give them credit for, and I’m trying to expose some of those problems. At least as I see them!

I hope that clarified my position a bit, but thanks for critiquing it–I need these questions/suspicions!

Thanks, Kate, I see much better what you mean now. While I haven’t read Deogratias, what you describe sounds similar to the ways in which Spiegelman and Sacco destabilize their own narratives. Meta comics are really just advanced meditations on information and media literacy, right? And that literacy can be used to interrogate the past as well as to inoculate consumers of media against the “emotional contagion” you mention.

Anyway I see where you’re coming from in saying that “truly embodying another’s perspective” is hard work that most consumers aren’t really up for, but your views on legit empathy seem to me dangerously close to the notion of Truth with a capital T. To me the entire point of meta comics is to undermine that myth. Just as there is no real objectivity, there can be no ideal form of empathy. Empathy is itself imperfect and deeply subjective by definition, skulking about as it does at the intersection of intellect, imagination, and emotion.

IDK, there so many different degrees of intentional manipulation (propaganda vs. NGO advertising, and then also the more remote category of art) under discussion here that I’m having a hard time tracking the argument. But I think the part I object to is this notion of readers who “have not taken action commensurate with that emotional connection,” as though those things are objective and quantifiable. It’s double trouble, because the implication is that there’s a “true” narrative that you can master if you’re informed enough–as well as a “true” response to it. In your discussion of how we might best emotionally and materially engage with that photo of the starving child, for instance, you present a hierarchy of engagement (valuing a boycott over a donation). To me this is precisely the sort of closed reading and dictated response that meta work tries to resist and discourage.

Anyway, sorry to pick, this was a great read.

I appreciate the picking! I think part of the problem you’re seeing is the problem I had composing a very short piece based on about 6 years of research and 150 pages of writing–I see the issues you’re having with some of the connections and explanations, and in part, I just didn’t want to ramble on for several thousand more words trying to clarify. I felt like I was testing readers’ patience at the current length as it was!

That said, I’m in agreement that there’s no capital “E” Empathy/capital “T” Truth. And part of that is the polemic end of the argument I’m trying to make: the overuse of the term “empathy” hides the fact that there isn’t empathetic engagement happening. Metacomics–like Maus, Deogratias, etc.–do wonderful things for pointing out the extent to which emotional engagement may be “misplaced” (i.e. we usually want to align ourselves with victims and heroes, rather than perpetrators and bystanders), incomplete (Maus in particular draws a vast deal of attention to how incomplete emotional engagement can be, same for Sacco in terms of point-of-view), and complicates all emotional engagement in the process.

As to the “action commensurate” element, this is what I was trying to indicate with the discussion of teaching the Literature of the Holocaust class that perhaps didn’t come across clearly enough. Many students–good, kind, smart students–had been trained to see emotional connection/empathy as *an end in itself,* rather than a starting place. And that, to me, was disturbing. It’s not just that empathy isn’t happening: it’s that a shadow-play of empathy is the *only* thing that is required.

This goes to the hierarchy of engagement, for which I actually do think there are better and worse forms of engagement. A donation is less involved, and ultimately usually less effective, than a boycott or other forms of action. I donate to various causes of course, because a donation is helpful. But it’s absolutely not as good as consistently boycotting (denying material sustenance to) a company, etc. Donation without other action backing it up has a much greater chance of simply *negating* unethical actions than other forms of protest. For example, if I donate money to Save the Manatees, and then go and buy a boat with giant propellers and wind up ripping up a manatee’s hide, then what good was my donation?

I’m very much enjoying this discussion, so please don’t feel disinclined from responding. I really appreciate how much you’ve thought through these issues, and it’s a pleasure to talk with you.

Kate, have you read Cynthia Ozick on Anne Frank? Quite withering on how contemporaries hijack her story.

Alex, thanks for the recommendation! I’d read it awhile back, but it hadn’t occurred to me in relation to this project–good connection!

Fwiw, I just published a discussion of the Wire at LARB that I think speaks to some of these issues.

Finally got to read it! Nice, Noah.

Pingback: KIbbles ‘n’ Bits 8/20/14: big old catch up — The Beat

Merci, Kate.