I was looking forward to reading Truth: Red, White, and Black following the smattering of positive notices the comic has received on HU of late. Noah’s recent article certainly gave me the impression that this was a comic which would transcend its roots in the superhero genre. The words “difficult”, “bitter”, and “depressing” are certainly words to embrace when encountering a Captain America comic.

I’ll not stint in my praise of the parts which do work. I like the naturalness of Robert Morales’ period dialogue and the shorthand used to delineate 3-4 characters in the space of a sparse 22 pages in the first issue. I like that Faith Bradley takes to wearing a burqa just to make a point. The idea that the first Black Captain America should be sent to prison the moment he steps foot on American soil is not only sound (linking it with the events of the Red Summer of 1919 mentioned earlier in the book) but resonates with reality.

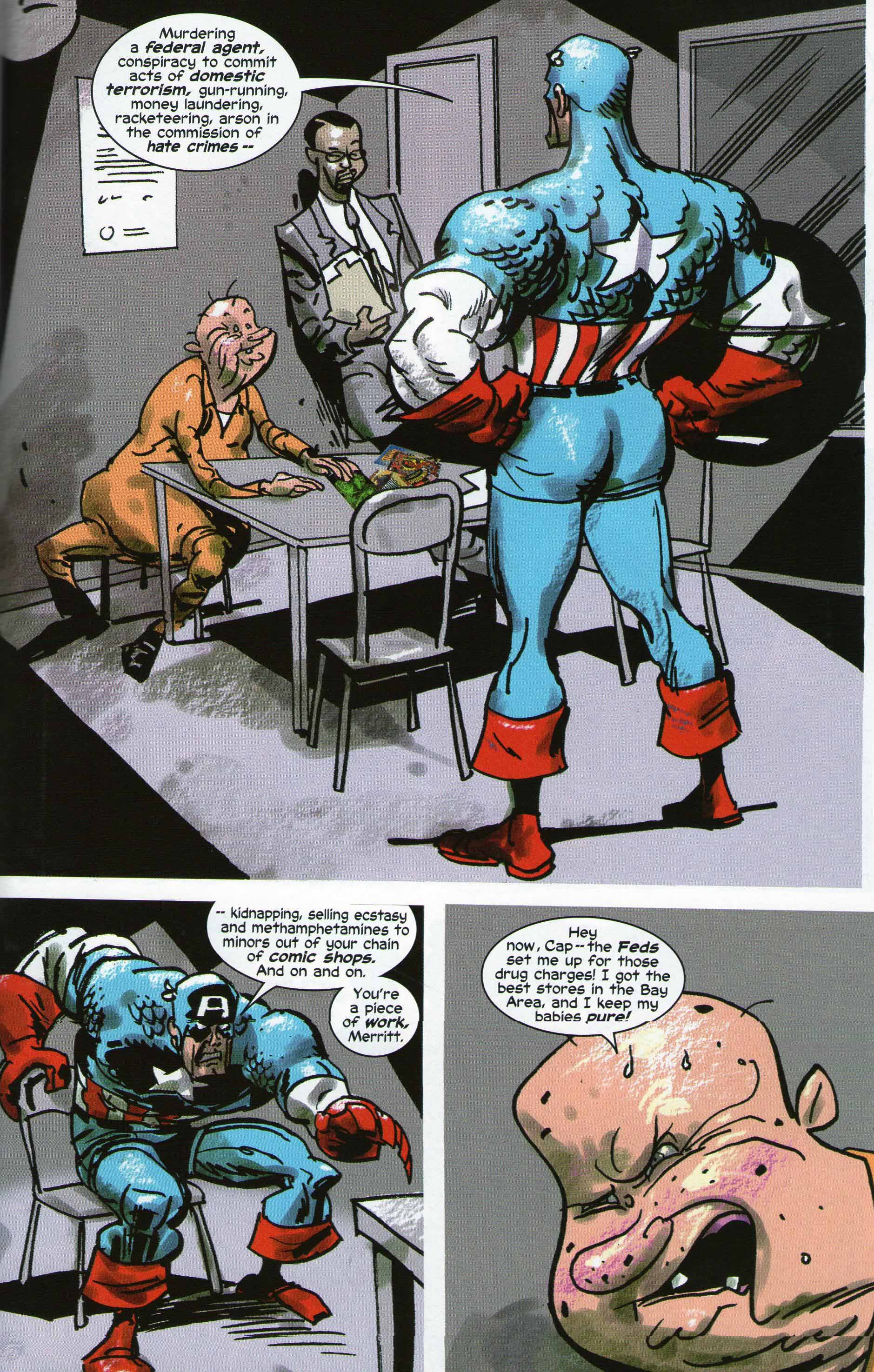

I like that Baker has a way with faces and makes the characters distinct even if they are almost all dispensed with in the course of 4 issues. His devotion to caricature (he is a humorist at heart), on the other hand, lends little weight to proceedings which are deadly serious—the violence is anaemic, the action flat, the misery imperceptible, and the double page splash homage to Simon and Kirby’s original Cap utterly out of place (or at the very least executed with little irony). I like the idea that when Isaiah tries to save some white women about to be sent to the gas chambers, they react to him with a fury as if asked to couple with a dog. It’s a troublesome passage of course since it implicates Holocaust victims in their own brand of racism.

One big problem for me, however, was that the comic wasn’t depressing enough. If the super soldier experiments are meant as a distant reflection of the Tuskegee syphilis study, then the comic doesn’t quite grapple with the true nature of tertiary syphilis and, in particular, the effects of neurosyphilis. The latter condition is described quite bluntly in Alphonse Daudet’s autobiographical In the Land of Pain and the effects are nothing short of a total breakdown of the human body, oftentimes a frightening dementia. Not the blood spattered walls which we see in one instance when a soldier is given an overdose of the super soldier serum but years of irredeemable and unsuspecting torture.

A nod to this lies in one of the test subject’s post-treatment skull deformation as well as Isaiah Bradley’s ultimate fate, but it barely registers in the context of a form wedded to the Hulk and the Leader. Yet even these moments are quickly discarded in favor of action and adventure—there is simply no time for the horror to deepen. The great lie underlying this tenuous reference to human experimentation is that no one has ever become stronger due to a syphilis infection—which is exactly what happens to a handful of test subjects. Not only is the condition potentially lethal in the long term but it has destructive medical and psychological consequences for the families of the afflicted as well as the community at large. To lessen the moral depravity of this historical touchstone in favor of saccharine hope seems almost an abnegation of responsibility.

The reasons for the strange disconnect between purpose and final product are perhaps easy to understand. No doubt editorial dictates and the limits of the Captain America brand came swiftly into play. But there remains the secondary motive of this enterprise. Reviewers have naturally focused on the “worthy” parts of Truth but in so doing they fail to highlight that it is in no small part an attempt to insert the African American experience into the lily white world of Simon and Kirby; an updating of entrenched myths and propaganda resulting in a nostalgic reinterpretation of familiar tropes (confrontation with Hitler anyone?). As such it partakes deeply of the black and white morality of the original comics— its easy virtue and comfortable dispensation of guilt.

It’s telling that Merrit (drug dealer, arsonist, murderer, and kidnapper), one of the most egregious villains and racists in the entire piece, is also a Nazi sympathizer. The other unrepentant racist of the comic (Colonel Walker Price) is a murderous eugenicists with his hands on the very strings of racial and genetic purity. Is racism only for villains? Why not rather the very foundations of American society; an edifice so large as to be almost irresistible. There are small hints of this throughout the text of course, but the desire for closure and the sweet apportioning of justice overwhelms a more meaningful and truthful thesis. While there is every reason to believe that racism against African Americans has improved haltingly over the decades, I would be more guarded in my optimism if our attentions are turned to people living in the Middle East and Latin America. In the real world, Captain America wouldn’t be one of the enlightened heroes of the tale, but one of the torturers and perpetrators. Even Steve Darnall and Alex Ross had the temerity to recast Uncle Sam (the superhero) as a paranoid schizophrenic in their own comic recounting America’s woes.

And what of the final fate of these villains? Well, we all know what happend to Hitler and Goebbels. That leaves Merrit who sits scowling in jail presumably imprisoned for life and Price who is threatened with exposure at a stockholder’s meeting by Captain America. And what of real life eugenicists such as Harry H. Laughlin, Charles Davenport, and Harry J. Haiselden—death by natural causes one and all, certainly not the judicially satisfying conclusion of public disgrace. The organizations which funded their work still abound in good health; their followers retiring to the safe havens of rebranding and renaming.

In the final analysis, Truth is still meant to be an uplifting story of tainted patriotism. As social history and activism by the backdoor Truth is commendable but it’s almost as if the authors were afraid to make too much of a fuss. Steve McQueen’s Twelve Years A Slave has no such qualms and is an orgy of violence, despair, and depression—a film which I have no intention of ever watching again. I have no intention of ever reading Robert Morales and Kyle Baker’s Truth again but, in this instance, for all the wrong reasons.

It is a problem trying to critique a structural problem with a genre whose narrative tends to rely exclusively on subjective solutions. I haven’t read Truth, but I’m not sure 12 Years doesn’t suffer from a similar issue: it sets audience identification easily with the slave, so no worry about all the non-evil slavery sympathizers that would’ve constituted much of the audience had they been born at a different time. When it comes down to it, there are clearly a few good guys and either the clearly bad guys or cowardly not so bad guys that no one in the audience is going to identify with.

Since superhero comics are based on subjectivized versions of whatever structural problems that they occasionally take on, perhaps its best just to accept that limitation and see protagonists and antagonists as metaphorical standins for the much more complicated realworld issues. Maybe treat them like moral goalposts. For adults, the comics like Truth are never going to be more than a satire of the genre, like putting nasty sexual issues in an Archie comic. (I mean, that’s pretty much what Alan Moore has always done.)

That’s an even lower opinion of the superhero genre than I have! I still think it’s possible for superhero comics to stimulate interesting thoughts on violence as well as other things, and not merely on a satirical basis. Examples are probably few though.

“Truth” doesn’t work as a satire. It’s dead serious about its place in the Marvel Universe, which is probably part of the problem.

I do think the Super Soldier serum narrative is a terrible metaphor for the Tuskegee experiments. Still it’s always used as a point of comparison in reviews and is clearly claimed by the authors in their choice of imagery. I suppose if the authors had decided to do it any other way, it wouldn’t be a Marvel comic any more. Or not one I would recognize.

Hmm, maybe I do have a lower opinion. To me, the best that they can do is reflect on the representation of violence, not really violence itself. I’m okay with that, even enjoying it, but I find it hard to take something like Truth as more than that. Anyway, that’s what I meant by calling it satire. At best, it can only expose the inherent silliness of the Captain American funnybook world. I guess to the degree that such comics represent realworld views, superhero books can critique/satirize the views typically offered, but they just shouldn’t be used as the lingua franca about the real world.

I’m more with Suat on this; I don’t think there’s anything inherently sillier about superheroes than about any other narrative form, really. There’s no reason superheroes can’t speak meaningfully about any number of issues (as I think Watchmen and the original Wonder Woman do, in very different ways.)

In any case, I would say that Truth qualifies as satire. I think Watchmen does too. I don’t think satire has to be funny (though Truth has a fairly bitter humor to it.) But it’s definitely mocking, or poking holes in, genre tropes.

I don’t necessarily disagree with Suat’s review. I would say that to me, though, the first part of the story especially was quite bleak, and seemed pretty impressively grim in its assessment of the U.S. Contrary to Suat’s take here, it seemed to me that the book made pretty conscious efforts to show that U.S. racial attitudes were congruent with Nazi ones, and to suggest that the U.S. record on race was in some ways as terrible as the Nazis. I was particularly struck with the scene where black soldiers were simply rounded up and shot by the U.S. army for basically no reason, and by the arrest of black Cap for taking the costume, and then he was imprisoned for 20 years without access to medical care. That’s pretty awful, and has the kind of bureaucratic, racist cruelty that I think rings pretty true.

Part of the issue is that in the early part of the book, it’s less clear that we’re dealing with just a couple of bad guys; the problem seems institutional rather than individual. When Steve Rogers shows up, that gets erased, and it is more about this guy and that guy being evil. As I said in my review, I think there’s a way to read the end as not a complete capitulation, but there’s no doubt that the book really would have benefited from a willingness to see Steve Rogers as something other than a saint.

But don’t you think satire requires some degree of exaggeration to emphasize the moral deficit in a particular position? I think Watchmen works as satire in some parts (not least the squid monster) but Truth seems devoted to the Simon/Kirby mythos and some form of “realism.” The tone from issue one seems to shout serious commentary on race relations. I suppose it depends on what kind of effect you think Baker was going for and whether he was thinking Kurtzman and Mad magazine.

The whole U.S. connection with the Nazis thing seemed a bit tacked on to me. A number of eugenicists in the U.S. were jealous of what the Nazis were accomplishing in the 30s and in the early 40s before the entry into WW2 (and vice versa). Lots of sickening correspondence still exists iirc.

I’ve basically forgotten about the part where the U.S. army rounds up the black soldiers for execution. Which sort of tells you how much of an impression it had on me. I know the comic wants me to care about the violence but the drawings just punctured that. It’s one of Baker’s least interesting works art-wise.

I don’t think satire has to work by exaggeration. I think trying to exaggerate when dealing with issues like racism, for example, doesn’t really work very well, since racist depictions don’t have any real world referent; they’re already hyperbolic and insane, so hyperbolic exaggerations of them (like Crumb’s) tend to just read as the thing itself, rather than as some sort of commentary on the thing.

I think that contrasting U.S. ideologies of heroism with U.S. ideologies of racism (as Morales and Baker do) is a lot more effective and thoughtful.

That’s interesting about the drawings…I rather liked Baker’s artwork. I felt like the violence was mostly presented as awful and confused and pointless (the sick, mentally damaged black supersoldiers fighting each other over nothing; Isaiah Bradley running into the Holocaust victims who don’t trust him; everything just pretty much turning to crap.)

I mean the kind of exaggeration directed at the oppressors as in A Modest Proposal. I just have difficulty seeing Truth as satire (or maybe just good satire) since everything is played so straight. All it seems to have done is to put the real world in a Captain America comic; so all it’s satirizing are the ridiculous comics, not life (which is Charles’ point I suppose). Almost everything “real” in it is more forgiving than the real world (except for the exploding soldier I think). It’s just more “real” than the average Captain America comic.

I guess it depends on your opinion of the average American reader – do most really think life is a Captain America comic?

The best, most interesting, part of the book is when Black Cap goes into the Nazi camps where experiments are being performed on the Jews. Clearly a parallel gets drawn between super-soldier experiment victims and those of the Nazis (and thus the Americans who administer the “experiments” get linked to the Nazis. The more Steve Rogers encroaches on the story, the more like a typical (crappy) superhero comic it becomes. Now I’ve got to read In the Land of Pain.

And it’s translated by one of your fave authors as well!

Superheroes can speak of any issue they want, but it’s always going to be a superhero doing the talking. They have certain ways of speaking that direct the conversation in certain ways. All genres aren’t equal in what and how they say things. Take away all the genre-reflexive commentary from Watchmen and you don’t have much. I don’t mean that lessens what it does, only that it doesn’t do everything. One aspect of the everything it doesn’t do is provide a staunch critique of political positions independent of how those positions function outside of superhero comics. I have the same problem with Jesus — you just can’t take anything he does as a straightforward reflection of or guide towards reality because of the superpowered good vs. evil genre he belongs to. The message is tied up with its genre. You can analogize past the genre, though …

oops: change that “outside of” to “inside”

Well…I think the ways people deal with power and politics is pretty wrapped up in genre too, is the thing. Captain America is not a bad metaphor for how America thinks about itself and behaves in the world. Watchmen’s critique of superpowers is also a criticism of how we think about superpowers, you know?

I’m not sure how far that gets you. A lot of people subjectivize objective problems, so superheroes make a good example of that — maybe the better term is synecdoche, not metaphor. Anyway, as I said above, to the degree people agree with the worldview depicted in superhero comics, the genre can critique that worldview. I’m just not sure you can tell a superhero story that ever gets past its generic tropes. They’re always going to be the primary thing that the critical superhero story is going to be about. The criticism of violence will be the criticism of the representation of violence in the superhero narrative, the criticism of egoism the criticism of the representation of egoism, liberalism, the representation of liberalism, etc. to whatever else is covered in Watchmen.

I guess I feel like with humans you’re always talking about symbols; reality is always represented. We don’t have access to some sort of absolute truth outside of language or representation.

As far as superheroes go, I think that narratives about violence (for example) in our culture are often very strongly tied into discussions about good and evil in superhero comics. So…critiquing those tropes seems like it’s critiquing tropes in the culture too.

We live in a state that has embarked on a four decade and rising carceral binge and that positions itself in world affairs as a savior by virtue of superior firepower. I don’t think it’s really an accident that superhero narratives are really popular here.

I’d certainly agree that there are other narratives that can better address other problems (romance is way better at thinking about the pros and cons of patriarchy, as just one example.) But genres by their nature tend to hybridize and morph. It’s certainly true that symbolic representations can only be symbolic representations, but again that’s going to be the case for any artistic or even communicative endeavor; it doesn’t have anything directly to do with superheroes.

Yeah, I’m skeptical of how much we can read prevailing cultural views on the criminal system into the Arkham Asylum’s treatment of the Joker. Or how much does the Red Skull really say about anti-semitism? Maybe he says that such things don’t belong too much in a Captain America comic up until entertainment got nastier. Past “there’s prevalent bigotry against the Japanese,” did the Yellow Peril type villains say that much?

I meant Chinese, of course.

Noah is probably thinking more along the lines of how some recent Wonder Woman comics reflect society’s anxiety about powerful women and their bodies. Speaking of the Joker (and women), the Killing Joke page where Barbara Gordon gets shot and paralyzed recently sold for $107,000 at auction.

As for good Captain America/Red Skull comics…I don’t think they exist. Some of the art is nice though.

I can’t say I was thinking about recent Wonder Woman comics or the Red Skull, I have to admit.

There are lots of bad superhero comics, like there’s lots of bad art. I think Watchmen and the early Wonder Woman comics and Morrison’s Doom Patrol and a few other things are really good art, which means I think they think about the world in ways I find insightful and moving. Like anything else, I think superhero comics need to be looked at case by case. I wouldn’t make any blanket claims for their quality, but I’m not willing to blanket condemn them either. I would say that genre has some limits and some obsessions, but I don’t think that fantastic art is more removed from “reality” (wherever that is) than realistic art. Just because it’s seen by a toad doesn’t make it trenchant social analysis, you know?

I can’t believe Charles has maneuvered me into a place where I’m defending superhero comics. I really resent that.

“I’m skeptical of how much we can read prevailing cultural views on the criminal system into the Arkham Asylum’s treatment of the Joker”

Charles, I think you’d enjoy this essay by David Bordwell beating up on what he calls “reflectionism”, if you haven’t already seen it.

Charles,

When say we like to “subjectivize objective problems,” I’m assuming you’re talking about telling a specific character’s story to get purchase on larger systemic problems that affect society, no? If that’s the case, then as Noah pointed out this isn’t genre specific, but yeah, the generic conventions of superhero comics work against the sort of nuance that gives this narrative strategy intellectual traction. Punching a person won’t solve systemic problems, and the perpetual “middle act” that characterizes shared universe storytelling militates against resolution. That’s probably why the few superhero comics that do address big problems address them at a remove, where superhero comics are an allegory for the story a society tells about itself (see Watchmen). In this way, a meditation on comics culture can function as an meditation on the culture that produced them. But that usually ends up as pretty thin gruel.

“and the perpetual “middle act” that characterizes shared universe storytelling militates against resolution.”

Osvaldo’s actually written quite a bit about why this is/can be meaningful, though. After all, real reality, as we understand it, doesn’t resolve. Why are narratives that resolve supposed to be more meaningful/realistic? That seems like a genre prejudice or preference rather than something that necessarily follows logically.

That Bordwell piece is pretty annoying. It seems like the whole thing is a plea for people to honor his expertise (normal everyday people shouldn’t be allowed to do film criticism without a license) and then a plea for people to write the kind of film reviews he likes based on the kind of expertise he’s got. Formal readings based on film history seem fine, but readings that think about whether films say something about society can be interesting as well. He seems to largely avoid the possibility that film makers are trying to talk to the present moment — but of course they are.

“One first step, for example, would be to consider Dawn of Planet of the Apes as following the plot pattern of the revisionist Western.”

Okay…but why the revisionist Western? Why was that chosen? Why is that a genre? What about that appeals to people (including the filmmakers?) The argument seems to be, you can’t look to movies for a discussion of contemporary America; as an example, here is this film that updates a quintessential American genre with a sci-fi futurist setting. He says he wants it to be about active filmmaking, and then says it’s all tweaking Hollywood archetypes, but of course that leaves you asking, where do these archetypes come from? What do they mean? Why are they appealing, or what sort of world is it that’s reflected in these archetypes? I don’t really see his preferred mode as any more coherent than the reflectionism his criticizing.

He wants film criticism for film scholars, who care more about film than about the rest of the world. I’m happy for such criticism to exist, but I wouldn’t want it to be the only kind out there.

As annoying as the Bordwell piece might be, it can’t be as annoying as reading anything Russ Douhat writes, I won’t read his film criticism, but, based on the times I’ve read it, I think the phrase “banalities about politics” should be the name of his NYT column.

I don’t think Bordwell’s attitude is all that uncommon amongst the academic and semi-academic writers in the humanities and the social sciences. There isn’t any room for engaging with a point of view that comes from a different school of thought, much less engaging with a layperson.

I think you and Osvaldo are right. It’s not like a definite resolution is impossible within the confines of an ongoing series, or that a lack of resolution is necessarily at odds with trenchant social or political commentary. That having been said, I think what I was getting at is that a lack of resolution makes allegory difficult, which is the preferred western genre of political storytelling. Not my preference necessarily, just a deeply conventional one. Of course, punching is also a go-to solution in allegory, which suggests that maybe I’m just off-base here.

Dean, I actually find Douthat at least sporadically interesting; though he can annoy me too.

I do have some sympathy for Bordwell…it can be irritating to see people who don’t actually have much expertise or necessarily insight into pop culture get taken seriously/get granted a huge platform just because they write about other things and the bar for blathering about pop culture is low. But, you know, that’s what you get for writing about things everybody cares about. Giant mega-popular films are really meant to appeal to a massive number of people; that means lots of people are going to have something to say about them. If that makes you sad, make your expertise about iconography in 16th century religious painting. Then no one will usurp you…and not incidentally, no one will click on your avowedly half-assed reading of an ape movie. These are the trade-offs.

Thanks, Jones, that Bordwell essay hits the target. (I really need to visit his site more often.)

Noah, he’s not saying an artist can’t use some popular work to say something the artist wants to say. He’s critical of the view (such as you often assume) that what’s being read in the art is the causative result of some socially determinative force, like light coming off a mirror. To use Suat’s example, Barbara Gordon being shot doesn’t have to mean shit about the general cultural approach to femininity. This will not be a popular view among a great many internet commentators on popular culture. It means that we’re ultimately just discussing art, not curing social ills.

Nate,

I think I agree with all of that. I’d suggest that Watchmen still offers a pretty subjectivized account of any social problems it represents. It’s still a struggle between good guys and bad guys, because it’s primarily a reflexive take on superheroic ideologies. It was different from the other superhero tales because of how much nasty real world shit Moore threw into the mix (and it’s narrative complexity, of course, but that’s not the point right now).

Anyway, I’m not opposed to using such things as analogies to real world issues, just dubious about the sort of “just so” cultural readings that ignore most of the contextual differences between the real world and the fictional superheroic one when a real world issue pops up in the latter (cf. Comics Alliance, etc.). The result is a simplistic causative explanation with a titillating headline. Was the women in refrigerators trope because of a ground swell of misogyny or the latent desire of our culture to kill women? Or was it possibly a combination of the fact that women were more often the side characters in the stories and, in the post-Watchmen era, brutally killing characters for cheap emotional effect was the thing to do, so when the lazy writer put these things together, guess who most often got the axe.

I’ll admit, it can be interesting (or at least entertaining) to watch Douhat do somersaults and backflips to defend some traditional idea without falling back on “tradition is good”.

My own take on pop culture criticism is that a lot of what passes for expertise or insight is really scaffolding erected to support some visceral “I like that” or “I don’t like that” reaction to a a particular bit of pop culture. Which is fine, a lot of interesting writing comes out of that, and the best of that will make me reconsider my own visceral reaction.

It’s irritating when the bar to discuss a work, or an idea is to have to accept some unquestioned assumptions of a theory (or Theory with a capital T) and/or to reject a plain language meaning of a word in favor of a jargon rooted in a particular school of thought. I’ll give you credit Noah, you’ve created a space where dilettantes like me can come an participate, even if it’s just to make the people I disagree with look good.

I’m guilty of the same thing in a different field, I find it really annoying when people enter a discussion on economics without having done the most basic homework on the issue in question. And I do that with a degree from a Post-Keynesian school, and Post-Keynesians know all about not having a seat at the table because they reject the dominant paradigms.

I wish I had something substantial to add.

I bought the first two issues of Truth when they came out, but I was just getting back into comics and was less rigorous about sticking with stuff I didn’t like to write about it (I wasn’t in grad school yet, didn’t have a blog).

I will see if the NYU library has it (or use ILL if it doesn’t) and give it another try.

But thanks for bring up my views on seriality and resolution.

You can get Truth on Pirate Bay, if you’re so inclined.

While I am not necessarily morally opposed, I tend to avoid that shit to keep my life simple. Plus, I can’t read comics on a computer screen.

But thanks for the tip.

“Barbara Gordon being shot doesn’t have to mean shit about the general cultural approach to femininity. ”

I mean, that’s an assertion on your part, sure. Does that mean that artists are in complete control of all meanings of their work? That artists are somehow shielded from cultural values, and therefore there is no way that cultural values could influence their thinking? That “archetypes” in comics have no relation to cultural values, and therefore it’s impossible that some of those cultural values might be expressed through said archetypes? Surely that’s as confused as a simple reflexivity model. It doesn’t seem like logic, or common sense. It seems like a way to avoid talking about something that you don’t want to talk about. It’s a political and ideological stance on your part, not some sort of rational obvious truth that makes you more common-sensical than your interlocutors.

Getting rid of intention entirely is silly, but getting rid of culture is just as dumb. Individuals are embedded in culture. Images of sexualized violence against women are really ubiquitous (as opposed to images of just plain violence, which are more common when depicting men.) Are you seriously suggesting that those cultural images of sexualized violence had no effect on the Killing Joke? Even though the editor in quesiton, when asked about the scene, is reported to have said, “sure, let’s kill the bitch”? Please.

“Was the women in refrigerators trope because of a ground swell of misogyny or the latent desire of our culture to kill women? Or was it possibly a combination of the fact that women were more often the side characters in the stories and, in the post-Watchmen era, brutally killing characters for cheap emotional effect was the thing to do, so when the lazy writer put these things together, guess who most often got the axe.”

First, I don’t think anyone said it was because of a groundswell of misogyny. Second, you seem to think that the second explanation — i.e., an increase in realism and general laziness — is somehow a contradiction to the idea that misogyny was at play. But misogyny is often just laziness; that’s how prejudice works. It’s falling back on stereotypes; it can be casual. There are sexist historical and genre reasons that women are side characters; there are sexist historical and genre reasons that “realism” for many means “more violence against women.” But those sexist things together and you get more sexism. I don’t think that’s a particular leap in terms of cultural criticism. Nor do I really understand why an imputation of “laziness” is somehow more neutral or less of a reading in to a story than an imputation of “sexism”.

This review of Olympus Has Fallen is one way I try to handle these things, I guess? I think the film has a pretty direct take on what America is, that take being tied closely and nauseatingly to racism, force, and torture. It doesn’t mean that this is what America is now; people don’t have to embrace that vision. But the film is definitely selling a particular vision of America; it’s in conversation with “reality”, not just with sci fi and action movie tropes. As it would have to be, since sci fi and action movie tropes are themselves in conversation with “reality” — or, in this case, with political memes, which are also symbolic, but which can get people killed.

Noah, I think you clearly confirm my characterization of your approach. We seem to agree on what you think, so I’ll leave it at that, since you know my rejection of it. I don’t think it has to be morally problematic to call a fictional character a bitch or to want to kill her. The guy who said that doesn’t necessarily believe that it’s okay to call real women bitches, or to kill them. That’s the kind of silliness Bordwell is rightly rejecting.

“You can get Truth on Pirate Bay…”

The original issues are also available on mycomicshop.com for a dollar apiece. That route is actually much, much easier for a lot of comics than hunting down the collected editions…

That…seems really weird, Charles. The idea that people compartmentalize their brains so completely that what they say in one place has impact on what they say elsewhere…I really don’t buy that. Art isn’t on its own world. It’s right here. I don’t think that the editor has to be an evil person, but he’s pretty clearly saying that his attitude towards the art is misogynist, and steeped in misogynist images. Misogyny is just an image and an attitude in any case; it’s a mindset, not a rock. If you don’t think it exists in language, then it’s hard to see where it — or indeed any emotional or ideological state — would exist at all. At that point, when you’ve separated language from reality that completely, it’s hard to see why you feel it’s worthwhile to say anything.

What do you call hated of fictional women? I’d say fictional misogyny. Differing attitudes about different things doesn’t really require much mental energy. Lots of things compartmentalize themselves. You seem to have trouble keeping fiction & reality separate, so try this: Moore wants to make Batgirl fly. His editor says, “let her fly!” I say it’d be silly to worry about men’s desire for female defenestration.

Charles,

I think your point about fictional misogyny works fine if all we’re asking about is the attitudes of the author or the editor. Things get more complicated if we ask into the degree to which depictions of misogyny shape attitudes toward women over time, in aggregate. Keep in mind that I don’t think there’s a simple answer to this question, and I understand that if we too quickly denounce a text on ideological grounds we can lose sight of nuances that might give us a more interesting and insightful interpretation (this would be the charitable reading of Bordwell, I guess). But if we take texts seriously enough to talk about them, then we need to leave open the possibility that texts reflect and shape culture, no?

Sure. But if he said, “throw the bitch out the window, I hope she dies,” it seems like that language has meaning. You think it does too. That’s why you wrote an example in which the language was different in order to make it seem like your point was valid (not that you did that consciously or anything, but often the way you say something, regardless of intentionality, can tell you something).

Differing attitudes about different things are different. However, the same attitudes about the same thing are the same.

You’re saying that attitudes towards women in the comics and attitudes toward real women are different. But where are these real women? They’re not in your discussion. “Women” is a word; it’s a symbol. The actual women aren’t sitting there on your keyboard. The women in the comics point to real women in an analagous way to how your word “women” points to real women. Reality is hard to pin down at the best of times, but when you’re talking about stereotypes, to say, well, this stereotype refers to real people, and that one doesn’t — how does that work exactly, Charles? Next you’ll be trying to argue that blackface caricature is meaningless because, well, it’s comics; it has no connection to real people.

The way we make political decisions, the way we think about groups of people, the way we communicate ideas — it’s all in language and images, it’s all using tropes and ideas and symbols. There’s no hard line separation between this symbol and that one. Again, simple reflection is simplistic, but bracketing art away from life, as if art can’t speak to reality, or isn’t meant to speak about reality — that’s silliness. It’s the naive anti-intellectualism of the sophisticate.

Ha ha, Noah, it figures you’d find it annoying, since the kind of thing he’s talking about helps pay your rent. I think your interpretation is uncharitable — it’s not a question of formal qualification so much as whether that kind of criticism is at all constrained by the works that putatively inspire it, or is just a lazy projection of the critic’s (quasi) a priori reading of the cultural context. Bordwell’s actually very open to film criticism from outside the ivory tower.

Hmmm…well, maybe, but if he’s not concerned about formal qualifications, why does he dwell on them? It’s possible it’s just tactical; i.e., he disagrees with them, so he brought up their qualifications because it’s a way to piss on them, even though he doesn’t really care. I don’t know that that’s more charitable to him, though it may well be more accurate.

Oh…and I don’t think the issue is ivory tower vs. not ivory tower. The issue is whether you’re in the film criticism club or not. That’s a somewhat different issue.

Hi Noah,

Have a lot of positive feelings about Bordwell’s general take, which seem just as aptly aimed at your average too-easy/never-wrong cultural-studies “it reflects the culture” gesturing. But I’ll skip all that, since I’m late to the conversation).

But I do think you can’t be right in your vision of the “in-club/outsider” distinction and its centrality to Bordwell’s argument. After all, excepting Douthat, his biggest example comes from J. Hoberman — and I’m pretty sure he’s a card-carrying clubbie, in most people’s books.

Peter

He’s written here about some of the differences between in-club and out-club criticism — he’s, actually, commendably open to criticism from outside the club. For the tl;dr version, read the section from this:

“What are the constraints on interpretation within the community of publishing critics, either journalistic or academic?”

to this:

“I’ve argued that the cue-inference method and the use of association to create patterns aiming at referential and implicit meanings are involved in all interpretations, staid or unorthodox. But the constraints I’ve just sketched aren’t so fundamental to interpretation as such. They typify the established critical institution, which includes journalism high and low, belles-lettres (e.g., The New York Review of Books), specialized cinephilia (eg., Cinema Scope), and academic writing.

Not everybody belongs to that institution. There are other arenas of film criticism, and there’s no mandate that discussion in those realms adhere to the constraints urged by professional criticism”

…it’s also worth noting that, when Bordwell started out, (I think) his own work was well outside the Theory club that prevailed in film theory of the time, so much so that he made his own club instead.

Yeah…I still don’t quite think your getting what I’m saying here, Jones. The club of people we’re talking about are the group of people who care a lot about cinema. It works the same in comics. There are various ways to be in the fandom (academia, long time collector, blogger, enthusiast) and people do take shots at other folks in the fandom…but there’s often a general circling of the wagons against people who aren’t in the fandom really, in part because they don’t care that much.

It’s the caring that’s the issue. Bordwell’s beef with Douthat, et. al., is that their diletanttes; being a film goer or a film critic isn’t central to their identity. He’s dinging them for that (whether opportunistically or because he really cares is hard to say.)

It comes up with a lot of film critics. Rosenbaum and Armond White probably don’t agree on much, but they both can seem to be coming from a place where failing to see a movie is an ethical lapse. That’s a convenient position to have if you’re being paid to see films.

Having said that, I haven’t read the whole 237 essay, but skimming it, it seems really thoughtful and generous and fun, and seems to contradict in some ways the other piece you linked. I like this Bordwell much better than that one (and appreciate that he’s willing to not be all that systematic in general.)

Nate,

To pick a current popular example, if you want to say all the violence in videogames reflect or cause an underlying increase in attitudes and dispositions, then you can’t just look at the videogames for evidence. You have to look at the decrease in violent crimes over the rise of videogames to see that the view is horse shit. I’d say the same of these charges of misogyny. You’re making claims about real populations based on what you see in a fictional environment. It’s basically another variation of lefty moral panic, but if I were such a leftist, I’d concern myself with UFC and football before I’d go to videogames or rock music or children’s television or movies or comics. At least there, you’ve got Noah’s real women being beaten by real men. Anyway, such hysteria makes for lame ideological criticism and as a leftist I don’t want to be associated with it. It’s been crap since juvenile delinquency, but my comrades never seem to learn a goddamn thing.

Noah,

All you’ve done with my hypothetical is to restate the original “kill the bitch!” which I was trying to get away due to your biases to see how much of a presumptive jump you’re making when taking the comment as cultural virus. I’m all for you or anyone else considering an empirical analysis of real people before making another sociological claim based on some piece of fiction. That’s what Bordwell is asking for. The absurdity of you taking some rumored statement by an unnamed editor regarding a fictional character as some indication of a prevalent belief of real people about a group of real people and then asking me to provide some real world evidence because of my skepticism is just too much. I’m the negative, man, you’re the affirmative! But, if you prefer, consider the same problem (fictional and/or comically stated views don’t necessarily add up to real world views) using yesterday’s hot topic in alarmist fandom: One of the more notable pro-women writers in superhero comics was revealed to be a fake feminist. How is that possible? The views are there, expressed in the comics, but he doesn’t treat women properly, even occasionally sexually harassing them? How confusing this compartmentalization.

As for stereotypes, they’ve accumulated meaning over time because of the shared language and culture in which they arose. When are stereotypes problematic and how are they perpetuated? That’s right, when people claim them based on false or fictitious assumptions about a real group of people without real evidence. It seems like a good idea — at least, it doesn’t hurt — to consider empirical evidence regarding that stereotype. That sounds familiar. Can you use a malignant stereotype without supporting it? Yes, easily, the same way you can fib or a fake feminist can write well-received superheroines. But if you reduce people to images, and can’t tell the groups apart (the mapped from the map) in this society of the spectacle, a hermeneutic circle, a world of misplaced concreteness, or whatever you want to call it, where compartmentalization is impossible (is it in or out? who can tell!?!), you’ve got no way of ultimately arguing against stereotypes. If anti-bigotry, you’d be your own worst enemy.

I’m pretty sure that I read in one of his intros that Bordwell came from a semiotics background.

“All you’ve done with my hypothetical is to restate the original “kill the bitch!” which I was trying to get away due to your biases”

So…now I’m the only one in the world who thinks that that language is offensive? Really?

As you say, I’ve reinstated the original discussion. You’re trying to change the discussion and claim you’re not changing anything because I’m biased (?) I’m telling you that I don’t buy it.

The rest of your discussion seems almost impossibly confused. No real people refer to women with violent language? Violence against women doesn’t happen? An editor saying a real thing is somehow not something an editor said because…what? And people can express different views in different places, therefore they’re not really fake, but yet they are? What?

My point throughout is that art is a medium of communication. Stereotypes exist in mediums of communication. Racism is broadcast and solidified through mediums of communication. So when you say, well, this can’t actually refer to sexism or to comics’ history of representing sexual violence against women, my response to you is that that’s ridiculous.

I don’t even think Bordwell would agree with you at this point. He’s not saying “films can’t speak to anyone about anything that matters!” He’s saying that looking at a film and saying it reflects the zeitgeist is silly. But with the Killing Joke, I’m not saying that it reflects *the* zeitgeist. I’m saying that the creators and the editor decided (out of laziness and a desire to be cool and edgy and real, probably) to present images of sexual violence. Those images connect to other images in culture, and those images have meaning in terms of how women are portrayed more broadly, in other art and in popular consciousness. Portrayals of women matter not because they reflect some zeitgeist, but because how we portray people is a big part of how we think about them and treat them. Violent sexualized images of Tutsi women were a big part of the propaganda which fueled/excused/prepared for the Rwandan genocide. If portrayals of women there could matter to the fate of real women (and for that matter real men) why exactly is this different?

I mean, Bordwell’s saying, reading Planet of the Apes as a metaphor for Obama’s presidency is dumb. Which it may or may not be, but seems like it has little to do with whether a representation of sexual violence is a representation of sexual violence.

The “can you use a malignant stereotype without supporting it” argument seems pretty idiotic. If you’re disseminating a malignant stereotype — if you’re drawing a blackface caricature (presuming you’re doing so straight, without making some sort of commentary) — then you’re drawing that caricature. You’re supporting it. Now, that doesn’t mean you’re an evil person in all respects, or that you’re always everywhere racist, or even that your true self is racist. It just means you supported a racist caricature. Is your understanding of the self so utterly impoverished that the possibility that someone might do contradictory things is impossible for you to get your head around? Is it all about saying, “I’m not a racist” and therefore excusing yourself from ever having to deal with these issues thoughtfully again? or what?

Your last point about the need for authenticity in order to have a basis for anti-racism is the one part of the discussion that is not simply hand-waving. Where reality is, and how to think about it or approach it, is a real problem, especially when you’re talking about issues of justice and equality. I guess I feel like it’s important to acknowledge the reality of suffering, but also to think about the way that reality can itself often be used as a way to rationalize or excuse suffering (racial differences or gender differences are “real”, therefore…) Recognizing that reality exists seems like it also has to include an acknowledgement of the extent to which our apprehension of that reality is always mediated by symbols, and an understanding that while reality can influence those symbols, the symbols can also influence reality, inasmuch as what we do in reality is often very much a function of what symbols we believe in.

“You’re making claims about real populations based on what you see in a fictional environment. ”

This really doesn’t have to be the case. I’m interested in Alan Moore and the Killing Joke because that’s what I’m interested in, not because I think it has to cause evil in the world necessarily. It’s a way to think about, for instance, how sexual violence is seen as legitimizing in narratives, or as making a work serious. You could also talk about it in terms of how audiences react, and whether it appeals to certain communities, and what that means (i.e., how does this fit into the very low number of women who want to read superhero comics.)

Lovecraft’s time was so thoroughly racist it’s hard to see how his really shockingly racist stories could have led to more or worse racism, exactly. But it seems like it’s still worth thinking about the racism in terms of how he deals with it. And if he’s a great artist (which I think he is) then maybe he also has insights into how racism works which might be valuable.

I feel like there’s a bit of a straw man argument, of both Bordwell and me. There are lots of different ways to think about the relationship between art and reality. I very rarely say anything like, “this violent thing causes violence,” because as you say that’s really hard to prove, and often probably isn’t particularly true (though sometimes it is.) You seem to be conflating that with an argument that it’s always wrong to talk about sexism and racism in works of art because, garble. That’s not even something that you believe, I don’t think; if you did you wouldn’t be having this conversation, I presume.

I don’t know…did you see my article about Mike Brown and the Uncle Tom stereotype at Pacific Standard? Is it wrong to think about literature and film in that context? or what?

I’ve gotta go, but I don’t believe for a second that you’d ever state something like X causes Y. Rather, you much prefer the vagueness of X contributes to/reflects the climate of Y. That way, you don’t have to really consider the connection of X and Y outside of the X. This is the debate I’m having with my my “not necessarily”s and “not always”s. Most of what you claim I’ve said has no relation to my position(s). This is surely my own hermeneutic circle (of hell).

Right; so if you say, “x reflects y” then you’re a simplistic fool; if you say, “the relationship between x and y is complicated” then you’re shilly-shallying and duplicitous.

I said that the use of sexual violence in the Killing Joke is the creators picking up on tropes that linke sexual violence to coolness, realism, and edginess. Do you disagree with that? It seems like it was in fact what you were saying earlier — except for some reason you think that if it’s a trope, it doesn’t matter. If lots of people say it, then obviously it has no meaning!

“Right; so if you say, “x reflects y” then you’re a simplistic fool; if you say, “the relationship between x and y is complicated” then you’re shilly-shallying and duplicitous.”

It’s more complicated than that.

Yep, Dean.

A critic is a simplistic fool if he takes his reading of a Batman comic’s ideology or whatever as necessarily true of the comic’s readership or production team WITHOUT actually investigating the real world causes he’s claiming to exist. He’d be duplicitous if, in recognizing what’s necessary for making such a causal claim, he regularly acted as if such a cause were true while only using the “it’s in the environment” defense. He’s not simplistic by simply making causal claims and looking to see if there’s evidence.

Noah, I’m seeing at least 3 separate arguments that you mush together in tarbaby form (here and typically) as if they were all the same. (1) Whether some symbol or expression is bigoted (e.g., blackface caricature); (2) whether the use of such a symbol or expression is necessarily bigoted; and (3) whether the appearance of these symbols or expressions have to be caused by or reflect a general cultural view or even a personal view (on the part of the reader or author). I’m running out of steam, so this is my summation and attempt to unstick myself:

(1) I haven’t denied that blackface is a bigoted symbol, or that there are symbols that convey bigotry like any word conveys a definition. Yeah, blackface is a bigoted symbol, even if an individual doesn’t want it to be. This has nothing to do with my expressed views above.

(2) You can use such a symbol without being bigoted, however. To pick easy examples Spike Lee did it with blackface in Bamboozled and Dave Chappelle did it with the KKK outfit in his variety show. I don’t think ‘bitch’ is a bigoted symbol like those, but even granting that it is, you can see teen girls using it in a nonbigoted fashion in The Bling Ring. The point: such art isn’t bigoted because it contains symbols of bigotry.

(3) This was actually the argument. I expressed skepticism towards reading real world views from fiction. Bordwell gives good examples for why my skepticism is warranted. But as I originally stated, I see value in critical analogies, just don’t forget you’re making an analogy. It’s certainly not impossible that the appearance of some attitude or belief in a superhero comic reflects a prevalent cultural view, but you need more than critical speculation to demonstrate it. Not that there’s anything all that bad about speculating, just don’t go off half-cocked with a cultural agenda based solely on that speculation. Thus, if you’re going to argue that changes should be made in some art medium, then you better have some real world evidence that the art reflects or causes or adds to the problem you’re speculating about. When real world violence is going down while the consumption of the supposedly problematic violent media is increasing, you should come away with the notion that you’re wrong, not just turn to more speculative analysis of the art.

As far as I can tell from skimming the essay on Mike Brown, I don’t much see the analogy to Uncle Tom’s Cabin as necessary to explain the use of “he’s no angel,” but it’s an enjoyable, creative reading that doesn’t seem inherently problematic to make, since it rests on textual comparisons. (Another more boring possibility is that the expression is simply a way of commonly deflecting irrelevant issues, a preemptive defense: e.g., now that more facts are known, Brown probably seems like a real piece of shit, but that doesn’t justify killing him.)

“now that more facts are known, Brown probably seems like a real piece of shit”

I realize you’re probably exaggerating, but…he really doesn’t. He just seems like a kid mostly.

I don’t disagree with the blackface point that the imagery can be used in ways that critique it, as in Bamboozled (I said as much, I’m pretty sure.)

I don’t really follow this:

” It’s certainly not impossible that the appearance of some attitude or belief in a superhero comic reflects a prevalent cultural view, but you need more than critical speculation to demonstrate it.”

In the context of the discussion about the Killing Joke. Images of sexualized violence against women are everywhere in our culture. Actual abuse and violence against women is quite common as well. So…what’s your objection to talking about the relationship between those two things exactly? I’d agree, saying the comic causes the violence would be a bit much, but saying, hey, here’s this image of sexualized violence in the comic, these images are used all over the place — why is that going out on a limb? And again, what I’d say about violence in the killing joke is that it seems to be used as a way of showing that the comic is gritty and edgy, which I would argue is a stupid thing to do. What part of that do you disagree with? And what does any of it have to do with Bordwell’s argument about reading films as representing the zeitgeist?

Or maybe this is clearer. Bordwell’s objecting to folks who say that a film reflects political events. But with the Killing Joke, I’m saying that the creators picked up on certain tropes and are using them in a way that enters into an ongoing conversation, or discourse, about sexual violence.

That’s not saying that the Killing Joke reflects a rise in sexual violence (which I guess would be the reflection theory.) I’m saying that the Killing Joke has something to say about sexual violence — in this case, something stupid, unfortunately.

Just as Truth has something to say about America — and again,that something is stupid according to Suat (though maybe not quite so stupid, according to me.)

“if you’re going to argue that changes should be made in some art medium, then you better have some real world evidence that the art reflects or causes or adds to the problem you’re speculating about. ”

Bingo.

But who’s arguing that changes should be made to an art medium? Where is this person?

I occasionally argue that comics needs to get rid of the sexism. But that’s not because I think comics are causing sexism in the world. It’s because, (a) sexism is often tedious to read and (b) comics ends up alienating female readers, and comics is a small enough puddle that it needs all the readers it can get.

There’s plenty of evidence that art in some cases causes can contribute to prejudice and even to genocide (Nazi propaganda, Rwanda propaganda.) Then there’s pretty good evidence that in some cases art doesn’t necessarily do a whole lot in terms of contributing to violence. Presumably most instances are somewhere in the middle. But I think there’s a pretty big difference between, say, Anita Sarkeesian saying, sexualized dead bodies in video games are similar to sexualized dead bodies in fashion art, and all treat dead women a lot different than they treat dead men, and someone saying that Wall-E reflects something or other about Obama’s America.

In critical and cultural studies the claim is rarely that the products of the culture industry simply reflect their social and political environments. The claim is that the products of the culture industry can provide insights into the contradictions inherent to the dominant ideology. It has nothing to do with effect, at least not in an instrumental sense. It has to do with how certain lines of thinking come to seem natural and others aberrant.

Noah –

Apologies for painting you with the broad brush, not like I’ve done an exhaustive search or anything, but I can’t recall you ever suggesting that a work should not exist/should not be read because it’s sexist.

However, that being said:

1. It’s not like there aren’t people who suggest that works be made unavailable because of sexist content. For example, Batman: The Killing Joke

http://bannedbooks.world.edu/2013/05/15/banned-books-awareness-batman-the-killing-joke/

2. Certainly there are critics who suggest direct links between sexist works and real word sexism. You’ve published at least one:

https://www.hoodedutilitarian.com/2013/02/retreat-from-the-citadel-confessions-of-an-ex-comic-book-reader/

3. I had no idea you had such concern for the health of the comic book industry! You’re to be commended for your desire to increase the size of the market.

4. Since that particular concern is about the market for comics specifically, is it safe to assume that your problem with sexism in other media is that you’re bored by it? If that’s the case I really don’t have any argument with you, that’s a very personal reaction and you’re entitled to it. I do think that give you about the same moral standing to objecting to sexism in the arts as the cretin who sees that cover and thinks “Gimme more Manara! Yay butts!”

5. While you’re apparently not part of this group Noah, it is clear that there are critics who find a causality/reinforcement of sexism in the real world. I do wonder though, if sexism is an evil, and sexist art contributes to that evil, isn’t the moral position to call changes to/a priori elimination of/censorship of those works? Perhaps not, if freedom of expression trumps reduction of sexism.

6. “But I think there’s a pretty big difference between, say, Anita Sarkeesian saying, sexualized dead bodies in video games are similar to sexualized dead bodies in fashion art, and all treat dead women a lot different than they treat dead men, and someone saying that Wall-E reflects something or other about Obama’s America.”

Sure there’s a difference, one is a 500 word paper in a high school English class, the other sounds like tedious navel gazing.

I’ll end with another example of a critic suggesting a causal link between sexist comics and real world sexism.

” Orion’s sexual harassment is cute and funny and even a little shocking (which is why it’s included) — but at the same time it’s normalized and invisible as sexual harassment. If it’s okay and funny to do that to WW, who has superpowers, who isn’t it okay to do it to? If WW can expect sexual harassment at work, then who can’t? It’s using a feminist and female icon to say that women and feminists have no recourse and should have no recourse when they’re harassed.”

See, that last bit is saying, “this comic says sexism is fine. It’s message sucks.” There’s no claim about who is going to follow up on that. Mein Kampf says you should kill all Jews. Do people who read it now believe that? Some do, most don’t. It’s still an evil book, because what it says is evil. Right?

My interest in the audience for comics is in part a moral interest. Comics is a community I’m part of. I don’t want it to be exclusionary and insular, because I think those things are bad. I think caring about your community and how it treats people, as readers or in general, is a moral commitment.

I certainly think that sexism in comics is related to sexism in the comics community. People sending rape threats because someone criticized a comics cover for fetishizing underage girls; that seems like there’s a link there, right? The link isn’t necessarily, representing sexism causes sexism. Probably the people who were going to send rape threats were sexist assholes before they saw the stupid cover. But their interest in alienating women and the covers disinterest in speaking to women seems like they’re congruent.

Presumably you agree that art can and does affect attitudes in some ways; otherwise your left denying that Rwanda anti-tutsi propaganda or Nazi anti-semitic propaganda mattered, which is pretty clearly false. I don’t think that comics sexism has as direct an effect as that (it hardly has any readership, for one thing.) But representations of sexism still exist in an ethical context, because saying, “women are inferior” is itself a statement that can be evaluated ethically, and because there is a relationship between what comics say and the community of readers, which is complicated, but “complicated” here is not usefully reduced to “there is no connection, who cares.”

“It’s still an evil book, because what it says is evil. Right? ”

I dunno, Noah. If there is no real world harm from the book, be it Mein Kampf or Wonder Woman, I think “who cares?” is a reasonable response.

Clearly, community aside, your major issue is that that the sucky message of sexism in Wonder Woman is tedious. Another case were “Who cares?” is a reasonable response.

I think propaganda more reflects existing attitudes in the society than creates those attitudes. Mein Kampf is an interesting case, the Wikipedia article looks like it’s decently sourced, and if it’s correct, Mein Kampf only sold about a quarter million copies from it’s publication to the time Hitler became chancellor and sold 10 million copies thereafter. Mein Kampf became popular because Hitler became chancellor, Hitler didn’t become popular (and chancellor) because of Mein Kampf.

Admittedly, some societies have decided that Mein Kampf is, if not evil, dangerous and the work is censored. Others have decided that the work should be available.

Generally Noah, while the correlation type of criticism can be interesting to read, causal linkage if and where it exists is far more interesting to me because it turns the discussion to real harms. I also think correlation based criticism tries to have it both ways, and that often, the critic really is trying to imply causality, but when pressed on the causal links, backs away from causality, sometimes with the explanation “it’s complicated.” That can come across as “shilly-shallying and duplicitous.”

I recognize though, that might be my own bias toward real world impacts in action. If I enter a conversation, perceiving it’s about real world impact, and find that I’m not, I might tend to think the goal posts have moved.

“I think propaganda more reflects existing attitudes in the society than creates those attitudes.”

Well that explains your position. You basically think that what we read has very little effect on what we think. So from your point of view, our political/cultural views are down to what? Family and friends?

Mein Kampf is a good example then. It didn’t sell much…but the ideas in it are enormously influential for a lot of reasons. (The history of the Nazis I’m reading suggests that it was actually required for every household to have one, pretty much.) So, the book tells us a lot about anti-semitism in the third reich, yes? That’s hardly “who cares.” it’s not necessarily, this caused that, but thinking about anti-semitism in Mein Kamps if pretty relevant to one of the worst genocides in the history of the world. “Who cares?” there seems like a lot of people.

As Suat suggest, if no one pays attention to anything they see or hear, how exactly does learning happen? Why does anyone bother to speak in art if they don’t think it’s going to affect anyone? It just seems like a really impoverished understanding of communication and art to me. Direct effects are difficult to parse, but folks who tortured at Guantanamo said they were inspired by 24; people issued rape threats because they saw a piece of criticism (which is a work of art); you’re typing away on the keyboard in response to an essay, which is criticism, which is art. What you read influenced you. Why shouldn’t it influence other people, perhaps in complicated ways, but nonetheless?

Seriously, if you only care about real harm, nailed down and certain, what are you doing here? Do you think I’m causing horrible, real harm because I’m writing about sexism in comics? If not, what’s it to you? Isn’t it shilly shallying and hypocritical of you to keep saying that you only care about this thing while spending all these words and time talking about something which you’ve strongly asserted can’t possibly matter?

Seriously, why are you here? What motivates you to talk here? If you can interact with words and they prompt responses and an investment on your part, what framework are you working in where that can’t affect anyone else?

I think family (both environmental and genetic) and friends have a lot more to do with our political/cultural views than a lot of people think. I think people tend to seek out things to read things that reinforce those biases, and tend to reject readings that contradict those biases.

That being said there is room at the margins for people to accept new ideas/experiences; to be be persuaded. Up thread I said

“My own take on pop culture criticism is that a lot of what passes for expertise or insight is really scaffolding erected to support some visceral “I like that” or “I don’t like that” reaction to a a particular bit of pop culture. Which is fine, a lot of interesting writing comes out of that, and the best of that will make me reconsider my own visceral reaction.”

Replace pop culture with politics, or, sadly, biology or climatology. I think there is probably more room to change thinking on things that are less identified with, for lack of a better word, tribalism. Climate science was fairly uncontroversial until the predominant view of climate science was popularized by a leading member of one of America’s political tribes.

Admittedly, there must be some holes in my theory (or whomever I absorbed it from because if fit my preconceptions), because I don’t think it does a good job of explaining how fast the culture became accepting of same sex marriage.

That propaganda seems effective isn’t surprising, it plays on existing tribal biases and is designed to persuade. I just don’t think something like diegetic sexism has nearly the same, if any, impact at all.

The ideas in Mein Kampf had a large impact not because they are written in Mein Kampf, but because they were held and dby a charismatic politician. Hitler was evil. Hitler’s ideas are evil. Mein Kampf is a book.

I’m here because I find it entertaining and jobwise I’m either really busy, or not particularly busy at all, during the latter times, HU beats Candy Crush. It’s fun to hang here because I do have visceral “that’s crazy” reactions to most of what’s written here, and I like to kick the ideas around. But I don’t think for a minute that most of the articles and all of the discussion threads are anything more than mental masturbation by the participants. I rarely post in the evenings or the weekends, because that’s real life time. I began reading here because it’s the main place Charles Reece writes these days, I’ve been reading and interacting with him online for years. It isn’t anything particularly important to me. If you took your website offline tomorrow, I wouldn’t really miss it. If you were ask me to stop posting here, I will without looking back.

I think that some ideas are more important than others. For example, I think the liquidity trap is a far more important idea than any “insights into the contradictions inherent to the dominant ideology.” The econ blogs are pretty much echo chambers, divided into ideological camps. There is actually clash of ideas here, and while I don’t think anyone will be convinced by anything anyone else writes, the give and take is fun and sometimes educational.

No…that explanation of Mein Kampf is really simplistic. The Nazis weren’t successful because Hitler was really charismatic. I mean, that was one factor, but he was charismatic in no small part because he articulated ideas that were popular — anti-semitism, anger over the loss of World War I, etc. Mein Kampf (supposedly; haven’t read it) distills those ideas. It’s a reflection of things that were important in society, and it solidified and provided an argument for and a blueprint for what was to come.

Mein Kampf is a book filled with ideas that are evil. I don’t really get the semantic shilly-shallying, especially since you’ve come out against shilly-shallying.

I don’t really buy your claim that you’re spending all this time, yet somehow it doesn’t matter, therefore art doesn’t effect you. How people spend their time matters a lot; what you engage with is part of who you are. Your effort to disavow that is just more time spent by you engaging with the brain that you say doesn’t care. If you’re in the room, you’re in the room, you know? Re: Charles; art is also a community. That’s another way it matters, not another way it doesn’t.

Noah – There were something like 74 million Germans and Austrians in 1933, 240,000 copies of Mein Kampf were sold before then, so even if every copy was read by 3 people, that’s still only 1% of the population. Hitler’s ideas were very popular in Germany for all the reasons you stated, but Mein Kampf could not have been a very important channel for distributing those ideas prior to his chancellorship. His speeches on the other hand, those are performances.

Hitler wrote Mein Kampf while sitting in prison, while he didn’t really have anything better to do (that sounds familiar), his rise to power and dissemination of his ideas would have happened anyway because he was the right guy at the right time.

“I don’t really buy your claim that you’re spending all this time, yet somehow it doesn’t matter, therefore art doesn’t effect you.”

I wouldn’t buy that claim either, good thing I didn’t make it. Have I spent a lot of time here the past few working days, sure. And generally how people spend their time matters, but not all time is created equal. My participation here at this time has a very low opportunity cost, I can do this in between reading other things online, text family and friends etc. I wasn’t too far off the mark when I implied my next best alternative was Candy Crush.

I get why this stuff is important to you and most of the folks here, you’ve clearly spent years of your lives thinking through these ideas, that’s an investment of time you don’t make unless you think something is important. I’m nothing more than a dilettante in your world. I have no illusions that anything I say on the topic of art hasn’t been said better by someone else, or that those ideas haven’t been argued and re-argued for decades if not centuries.

There are rooms and then there are rooms. HU is probably more than the road trip convenience store, but it’s not like hanging out with the family at Thanksgiving either. Maybe that bar you step into for a beer for a few times a year.

Sales figures aren’t going to work, I’m pretty sure. Massive numbers of copies were given away (or that’s my impression from the Richard Evans books I’m reading now.)

Now you’ve moved from saying that writing doesn’t affect the readers to saying it doesn’t even affect the writers. Hard to see why any communication would matter to anyone at that point.

Again, disavowals aren’t really taking you where you want to be, I don’t think. You’re admitting that art (criticism, communication) affects you in a small way — enough for you to spend quite a bit of time here. If arts small effect here is that you spend quite a bit of time, why can’t art have a bigger effect in other cases? And why does there have to be this binary affects/doesn’t affect? Surely there can be more complicated relationships between what you read and what you do.Thinking about that seems worthwhile to me, for any number of reasons, some of them ethical.

You’d have to separate the total distribution (sales+free copies) in the period before Hitler came to power (when the distribution of those ideas would really have mattered) vs. the time after he came to power, when yes, a lot of copies were given away. You want to show me that your writing (art?) can impact me, show me numbers, on this I can be convinced.

I don’t think I ever said that art could not have an impact on people in real life. I maintain that it’s a lot less likely some people might think, and that it probably doesn’t affect things like people’s basic political orientation to any great extent (so yes, propaganda tends to reflect society more than society tends to reflect propaganda). What I’ve said is that I would prefer to read criticism that argues those impacts, because I think a real world harm is more important than a diegetic harm, or a hypothetical harm that is the result of some bad/evil idea. I don’t think Robert Jones made a very good case for causality in his Wonder Woman article, but at least he made the argument. That’s interesting to me. Pointing out that society is sexist and art is sexist, and there is some ill-defined but most assuredly complicated relationship between those two facts is not so interesting to me. Pointing out that art A is sexist and Art B is also sexist, and there is some ill-defined but you’d better believe it complicated relationship between those two facts is not so interesting to me. Pointing out that art C is sexist and thus tedious seems really trivial to me, a pleasant diversion maybe, like posting here, but trivial.

I think there is a tendency to assert complication without actually demonstrating complication.

Of course I just asserted that tendency instead of demonstrating it…

I’m pretty interested in art. Part of that is being interested in what art has to say. It’s the same reason I’m interested in talking to you, you know? How is your view of the world put together; what does that mean? I think those things are interesting and valuable because other people are interesting and valuable,and how they see the world matters.

You seem like you’d rather be reading sociology or social science about art than criticism. That’s fine. A lot of that stuff seems (ahem) fairly simplistic to me; I think criticism, which is itself closer to art, gives you a better sense of how art works than looking to some sort of quantitative social science paradigm (and who exactly convinced you of the value of quantification, I wonder? Was it handed down to you by the gods of reason? Did your parents sit you on their knee and babble about methodology? Or maybe you read something somewhere?)

Value of quantification? That’s easy, my whole life I’ve been rewarded and valued for my ability to quantify things. Innate ability recognized very young and nurtured by family, friends, society (public schools), reinforced by my choices to further educate myself on things quantitative. I absolutely think there are questions that can be answered by quantification. If you were to show me that a significant number of Germans were exposed to Mein Kampf prior to 1933, I would concede your point. I would guess a lot more people heard speeches and read newspapers supporting Hitler’s views than ever read Mein Kampf. Not that I think a lot of those people had took much convincing.

My inclination and education are toward the social sciences (and I picked economics over history or poly sci because it’s more quantitative, even then I went to a heterodox school so there was a lot of focus on History there via Marx) so I guess it’s not surprising that would be my approach to these things. But I think sociology and simplistic are synonyms so maybe not.

I like criticism because, when it’s good, it’s a form of argument – assertions, reasoning and evidence. It’s in the reasoning and evidence pieces where there are some lessons to be learned from rigor and evidence. Complicated realities can be modelled more simply, and those models have a lot of explanatory value. I think the dichotomies that these discussions slip into are a version of that. Let’s test the extremes and see what shakes out.

It could be though that the general type of cultural criticism practiced around here is, at base, too personal to force that sort of rigor on. I think people here tend to make pretty good cases based on their assumptions. It’s often the assumptions I find questionable.

I do agree people are valuable, but I’ll admit to a bias in looking at their value as large aggregates. That makes me shortsighted sometimes.

” If you were to show me that a significant number of Germans were exposed to Mein Kampf prior to 1933, I would concede your point.”

Again, I’m just reading Richard J. Evans’ history, and it sounds like virtually everyone in Germany would have had a copy. Hard to say how many read it; it’s rambling and uninteresting. So depends on what you mean by exposed, but there doesn’t seem to be much historical question as to the fact that it was everywhere in Germany under the Nazis. (That’s a historical truth, not a quantitative one. Different, but still important, I think.)

I don’t have anything per se against quantification. It often doesn’t work super well when talking about art; you can’t really perform experiments to see how people react to art (or you can, but they’re always dicey and not especially convincing, for the most part.)