My wife has been trying to get our daughter to read Jane Austen since our daughter started middle school. She’s now a senior, and when faced with a summer reading list for A.P. English, she picked Pride and Prejudice because her teacher said he didn’t like it. She can be perverse that way, but her impish impulse backfired because then she couldn’t stop reading the entire six-novel Austen oeuvre (plus the incomplete Sanditon even though she can’t bear not knowing how a romance plot ends).

I theoretically read Emma in college, and I have an increasingly thin memory of Northanger Abby from grad school, but my wife gasped—Yes! Gasped, I say!—when I admitted at our dinner table that I had in fact never read Pride and Prejudice. The characters in Karen Joy Fowler’s The Jane Austen Book Club give the same reaction when the lone male in the club makes the same admission.

I’m teaching Fowler’s novel this semester as part of my New North American Fiction course, AKA “Thrilling Tales.,” so I’m braced for more gasps.

I stole the subtitle from the issue of McSweeney’s that Michael Chabon edited back in 2002. His pulp-reclamation project includes a range of highbrow authors writing in lowbrow genres: horror, scifi, mystery, but not—I only recently noted—romance. Same is true of the issue of Conjunctions Peter Straub guest-edited the same year. So the proud gatekeepers of 21st century literature were allowing in zombie ghosts and steampunk Martians, but no tales with “Reader, I married him” closure.

I theorized the prejudice was against formula: any narrative with a predetermined ending is by definition formulaic, and so not literary. And though I think that’s largely true, the prejudice runs deeper.

My daughter told me I had to read Pride and Prejudice to avoid humiliation in my own classroom. My students will have read it, she said, and since Fowler’s novel references it so deeply, and since it’s considered the best of Austen’s novels, and one of the best novels of English literature, I agreed I had no choice. This implies I was resistant. I wasn’t. Fowler’s novel is brilliant (easily the most engaging metafiction I’ve ever read), and I had every intention of enjoying Austen too.

And yet why did I hesitate? And why hadn’t I included a work of romance in my Thrilling Tales syllabus the first time I taught the course? I’d covered so many other genre bases—time travel, superheroes, genetic engineering, vampires. It turns out the diagnosis isn’t all that complicated.

When I had a doctor’s appointment over the summer, I took the library copy of Pride and Prejudice that my daughter had read. The nurse (female) said, “Oh, what a good book.” The doctor (male) said, “Oh god, that thing.” He’d read it in his A.P. English class back in high school. I don’t know when the nurse read it, but I assume it was for pleasure. Non-literary female pleasure, the kind even the omnivorous Chabon and Straub couldn’t get there lowbrow brains around. 1930s space aliens is one thing, but Harlequin Romances? Please.

But what genre doesn’t suffer from bad examples? I’ve read some cringingly embarrassing sonnets, but they don’t reveal anything about the merits of 14-line rhyme structures. The best Shakespearean sonnet doesn’t reveal anything innately excellent about the form either. It’s just a form. And Shakespeare knew how to write in it.

Few authors are regarded as their genre’s best practitioners. Even fewer are regarded as inventors of their genres. Ursula Le Guin (for example) falls into the first category, but not the second. Jerry Siegel, the co-creator of Superman, falls into the second category, but not the first. If you consider a Shakespearean sonnet its own genre, then Shakespeare falls into both. So does Jane Austen.

I’m looking forward to discussing The Jane Austen Book Club with my class soon, but first a superheroic revelation of my own: Without Pride and Prejudice, my favorite 1930s space alien, Superman, would not exist. Jane Austen is Jerry Siegel’s secret collaborator, and without her, the comic book genre that followed Action Comics No. 1 wouldn’t exist either.

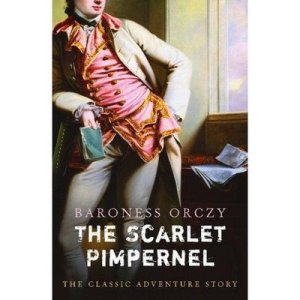

To the best of my knowledge, no one has ever drawn an Austen-Superman connection. But the line of influence is direct. It’s called The Scarlet Pimpernel. The novel was published by Baroness Orczy in 1904 and is one of the most influential texts for early superheroes. Its title character is often cited as the first dual-identity hero and the inspiration for Zorro and dozens of other pulp do-gooders culminating in Batman and Superman. Siegel was a Pimpernel fan and reviewed one of Orczy’s sequels in his high school newspaper. Take away Orczy’s mild-mannered Sir Percy and the mild-mannered Clark Kent vanishes too.

The Scarlet Pimpernel is also a romance, one that formulaically matches Pride and Prejudice. It’s told from the perspective of its female protagonist, Marguerite, who, like Austen’s Elizabeth, is blind to the true character of the novel’s hero. Elizabeth thinks Mr. Darcy is an arrogant jerk. Marguerite thinks Sir Percy is a cowardly fool. Or they do for the first halves of their novels, because after a pivotal middle scene (Mr. Darcy proposes, Marguerite confesses), the second halves are spent revealing Darcy’s and Percy’s secret heroism. Austen uses the word “disguise,” Orczy prefers “mask,” but both metaphors must be removed.

That also requires some suffering, since Elizabeth and Marguerite must recognize their mistakes in order to be united with their heroes. Austen says “humbled.” Orczy says, “the elegant and fashionable [Marguerite], who had dazzled London society with her beauty, her wit and her extravagances, presented a very pathetic picture of tired-out, suffering womanhood.” Unmasked hero and humbled heroine may now live happily everafter.

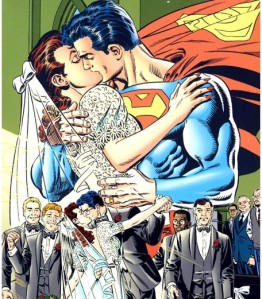

Jerry Siegel adopted the Austen-Orczy formula too. As long as Lois Lane can’t see through Clark’s disguise, she can’t be united with her Superman. But Austen mostly and Orczy entirely limit their perspectives to their heroines’ points of view. Siegel sticks with his hero. When Joe Shuster draws Clark changing into Superman, readers witness the unmasking, but Lois doesn’t. She’s stuck in the first half of Elizabeth’s and Marguerite’s plotline. Austen’s and Orczy’s readers learn with their heroines, but Superman readers can already see Lois’ mistake. Shuster even draws Clark laughing behind her back. She is “humbled,” but she can’t learn from it and so can’t be united with her would-be lover. The romance plot is frozen.

Siegel did try to reach the second half of Pride and Prejudice though—perhaps as a result of having reached marital closure himself. In 1940, two years into writing Superman, and two months into his own marriage, he submitted a script in which Superman unmasks to Lois.

LOIS: “Why didn’t you ever tell me who you really are?”

SUPERMAN: “Because if people were to learn my true identity, it would hamper me in my mission to save humanity.”

LOIS: “Your attitude of cowardliness as Clark Kent—it was just a screen to keep the world from learning who you really are! But there’s one thing I must know: was your—er—affection for me, in your role as Clark Kent, also a pretense?”

SUPERMAN: “THAT was the genuine article, Lois!”

The revelation completes the Austen formula. When Darcy tells Elizabeth, “You taught me a lesson, hard indeed at first, but most advantageous. By you I was properly humbled,” the two can unite because now they are on the same plane. Superman comes to his “momentous decision” after Siegel introduces the superpower-stripping “K-Metal from Krypton,” the only substance that can humble the Man of Steel.

But the story was rejected. An editor wrote in the margin: “It is not a good idea to let others in on the secret.” It would have run in Action Comics No. 20. Instead, Clark reveals himself to Lois in No. 662, fifty years later. They married in 1996, the year Jerry Siegel died.

Nice work, Chris! Of course, my nit to pick — at least as far as Superman goes — is that, unlike Darcy and company, Superman is never “humbled,” is never “mortified” (another key Austen term), never truly brought down to Earth. Elizabeth, Emma, and Anne all need their rigid and stoical Supermen to crack, to show their inner Kent — not the other way around.

Instead, the Superman storyline much prefers to celebrate the humbling and ridiculing of Lois, who in spite of her spunkiness, always remains on the butt-side of the joke, while the hero flies away free from her dreams and traps. And we are in on that celebration, every time Superman/Clark turn to the reader — or even to himself — and, with a grin, winks.

Mr Darcy, you’ll recall, had yet to learn to be laughed at. I’m not sure Superman ever learned.

Good point, Peter. Siegel follows Orczy on this point too. Sir Percy is merely unmasked, which is his wife’s humbling, not his own.

Really enjoyed this piece, though I confess you lost me as soon as you turned to Superman. The sad truth is that it’s not just Romance as a category that remains in what Chabon has called the genre ghetto, it’s most of “women’s fiction.” As you allude to in your anecdote about the doctor/nurse, books about women’s lives are widely considered to be for women readers. Books about men’s lives are of course high literature. It’s not just the subject matter, though; the author also figures in. As others have said before me, if Franzen were a woman, there’s no doubt his work would be on the pink book table at the bookstore.

I used to be on the pink book table too. I’m male, but since “Chris” is ambiguous, my publisher kept my photo off the back cover when my first novel appeared as a romantic suspense–another subcategory of women’s fic. Fowler is a brilliant and award-winning writer (her latest won the PENN/Faulkner I think), but even the Austen Book Club still has an aura of chicklit to it that I’ve seen turn away “serious” readers.

It’s funny; I had that gasp moment about Austen with my wife — she told me she didn’t like Austen and I think my jaw dropped. (I convinced her to try her again, and she was hooked. In return she convinced me to like D. H. Lawrence.)

I don’t know that I totally buy the Jane Austen inspiring Superman, even second-hand…but I do like the idea of contrasting Darcy and Superman. Obviously, Darcy’s super power is that he’s really rich (who needs super strength when you have Pemberley). The main difference between him and Superman (at least the Siegel/Shuster version) is that Darcy is fundamentally a good person.

Bruce Wayne has the same super power. I wonder if Pemberley has any secret caverns under it.

Oh, and I’ll add that Superman was “humbled” before he married Lois. He looses his super powers (I can’t remember how) before the wedding, so he’s just a mere human at the altar.

Great work as always, Chris!

And I want to note that when I saw the title of this post on the RSS feed, I KNEW it was you who had written it.

Many thanks, Osvaldo.

Noah sez:

“The main difference between him and Superman (at least the Siegel/Shuster version) is that Darcy is fundamentally a good person.”

Yes indeedy, Siegel and Shuster certainly did not mean to imply that a man who dedicated his life to saving lives and fighting crime could ever be “good.” That Doc Wertham was right about EVERYTHING!

Well, they may have meant him to be good…but he really comes across as a dick.

Wertham was right about lots of things, and wrong about some. But the compulsive panic with which he’s invoked by the fandom is just embarrassing.

I can’t speak for anyone else, but I invoke Wertham as a major proponent of the theory that one shouldn’t read superheroes as representing any real desire to do good: that their good acts were in fact a camouflage for the quasi-fascist bullying that the audience really wants to see.

Early Superman is without question an alpha male. If he sees a con-artist cheat a little old lady out of her fortune, he makes said con-artist wish he’d sought out safer employment defusing bombs. That’s the dominant S&S characterization I see, and I see no reason to object to it unless one wishes to re-interpret the narrative in the Mighty Wertham Manner. It’s arguable whether the character’s later history of messing with Lois and Jimmy takes all that much from the early years.

He treats Lois like crap, pretty much. He’s a bully; he occasionally engages in extra-judicial killing.

I mean, I see you saying that you’re cool with strong guys taking the law into their own hand, which is not exactly a refutation of Wertham’s point. Wertham says, bullies hitting people outside of the law is ugly vigilantism, and your response is, hey, the narrative tells me to trust the strong guy, and I trust the strong guy. Darcy still seems to me like a much more likable and admirable character (not without flaws or anything, but still.)

Not to say I hate the Siegel/Shuster comics. I enjoy the capitalists getting theirs. I wouldn’t want to ever meet that version of Superman, though (as opposed to say Eliot Maggin’s.)

Noah, Maggin’s Superman was also my favorite — and Mark Waid’s, I think (based on what he’s said). Maggin’s Superman wasn’t a bully; he really did care about right and wrong. But he wasn’t naive, and he wasn’t a wimp, either.

My expressed sentiments on the subject are a refutation of Wertham in that I recognize that S&S Superman is a melodramatic fantasy. Wertham’s project was to re-interpret all such stories as indicative of a real desire for bullying and/or lynch-law on the part of the readers. I recognize that such stories are fantasies in which good and evil are defined in simplistic– though not irrelevant– terms, for the sake of enjoyable escapism.

Giving the popularity of Superman comics in their early days, I don’t think there’s much evidence that they incited widespread vigilantism– which usually comes about because of perceived losses to one’s real-world interests, not because of some funny-book character.

“I don’t think there’s much evidence that they incited widespread vigilantism”

They were very popular at a time when we engaged in a world war, in which in the name of good we did a lot of pretty awful things, including killing a ton of civilians. I don’t think there’s a one to one correspondence (causation doesn’t equal correlation) but if you’re arguing that the correlation isn’t there, I would say you’re not being especially thoughtful.

Part of what Wertham is saying is that enjoying Superman is enjoying bullying in the name of righteousness. That’s what the fantasy is. I don’t see you really refuting that anywhere.

One can hypothesize, but not prove, a correlation between fictional power-fantasies and actual acts of aggression. But since you can’t prove it– and indeed, Wertham did not– then it becomes nothing more than a rhetorical tool; a club with which to bludgeon whatever one doesn’t like. What’s thoughtful about that?

I see the fantasy of melodramatic adventure– ranging from Walter Scott through Baroness Orczy through Superman (but not through Pride and Prejudice, methinks)– as one rooted in the awareness that real evil exists, however one chooses to characterize it. The fantasy is that of being able to beat evil decisively, without the many complications of real life.

Here’s a tangential question for you: if the raison d’etre of the superhero is bullying– why should superheroes ever face villains who can give them a tough fight? I’ll freely admit that most of Superman’s opponents are ordinary mortals– but why should the hero ever encounter even one Luthor, if the point of the narrative is to show lesser opponents being bullied?

There’s very little you can prove about the link between real world action and fantasy, as we’ve mentioned before. Does that mean that any reference to possible links is a rhetorical bludgeon and inadmissable because it can’t be scientifically proven? Or, you know, maybe part of the point of these discussions is to think about how fiction and reality connect, ambiguously, mysteriously, but nevertheless?

Re: bullying. I’d encourage you to read Ender’s Game, where bullying of Ender repeatedly becomes the trigger for murderous and apocalyptic force. Or you could see any discussion around “fake geek girls”, where the fact that some people have been bullied becomes an excuse for exclusion and quite often bullying in return. Or you could listen to any discussions about why it’s okay for the U.S. to bomb ISIS, or before that Hussein. The narrative pleasures of righteous violence always tend to depend on an apocalyptic, or at least serious, threat. The excitement of the bullying isn’t just the strong beating the weak; it’s the imagined violence of the weak against the strong which justifies massive retaliation. (One of the reasons that separating fiction and reality isn’t very convincing is that narratives are used incessantly in our political life to justify all sorts of policies. How do you separate a fictional narrative about Afghanistan from a fictional narrative about Superman?)

If you want another example, I’d direct you to Richard Evans’ three volume history of Nazism. Towards the end of the war, the Nazis became more and more murderous and killed more and more Jews. This was justified on the grounds, and out of the fear, that Jews controlled the Allies, and would wreak terrible vengeance on Germany if they were allowed to survive. So, in that scenario, the Jews are fantasized as Luther; they are dangerous and may give the hero a real struggle. Does that mean the Nazis weren’t bullies, because they constructed an opponent to beat up who they pretended was dangerous?

“I see the fantasy of melodramatic adventure– ranging from Walter Scott through Baroness Orczy through Superman (but not through Pride and Prejudice, methinks)– as one rooted in the awareness that real evil exists, however one chooses to characterize it. The fantasy is that of being able to beat evil decisively, without the many complications of real life. ”

I’d say that that’s correct. I’d also say that the fantasy (or recognition, whichever you prefer) that evil exists, and the narrative fascination of confronting that without complication, tends to be the rationale behind huge outpourings of violence in history. Think of the Terror in France; the fantasy of Robespierre is that evil exists, and that therefore it should be exterminated in an uncomplicated fashion. Same with the Nazis; same with us at Pearl Harbor; same with the Rwandan genocide. It’s quite unlikely that Superman was in the minds of any of these folks, but the logic of Superman which you describe is also pretty clearly the logic behind genocidal fantasies which have been carried out.

Does that mean Superman is a genocidal evil? No, of course not. It does mean that Wertham was correct in his analysis of Superman’s message, as he was correct about homosexual overtones in Batman and Wonder Woman. His recommndations for what should be done about that are largely wrong, I’d say, but he wasn’t misreading the material in front of him.

Incidentally, Jane Austen recognizes the existence of evil. But she doesn’t write stories where the pleasure is the fantasy of defeating evil without complications such as law, or morality, or worrying about the evil-doers humanity. (Not all superhero narratives do either. Watchmen doesn’t; the original Wonder Woman doesn’t; plenty of others don’t. The Siegel/Shuster Superman is pretty simple-minded, though.)

Oh, just looking back…I wouldn’t say that superheroes are just pretending to do good in order to bully. I’d say that fantasies about goodness and fantasies about power are intertwined with the superhero…and in modernity more generally as well, at least (and especially) since Nietzsche. Ben Saunders “Do the Gods Wear Capes?” is really good on this; you should read it if you haven’t. It’s great (and not at all anti-superhero.)

“Does that mean that any reference to possible links is a rhetorical bludgeon and inadmissable because it can’t be scientifically proven?”

By my lights such references are admissible if the critic in question frames them as a working hypothesis, and remains open to countervailing evidence. This Frederic Wertham certainly did not do, and his attempt to use the fantasy/reality correlation as indubitable fact was indeed nothing but a rhetorical club.

“Re: bullying. I’d encourage you to read Ender’s Game, where bullying of Ender repeatedly becomes the trigger for murderous and apocalyptic force.”

By chance I just reread it the other week. I could probably see Superman as being closer to the bare image of the bully– not the moral context, of course– than anything that happens in the Card novel. The things that the space military do to Ender are repellent, and yet, within the novel’s universe, they work: they serve as a sort of apocalyptic (to use your word) training that ramps Ender up to maximum survival levels. Card does at least open his novel up to discussion as to whether the military did the right thing or not in its genocidal course. I’ve some reservations as to how well he did it, but that’s a separate question.

“The excitement of the bullying isn’t just the strong beating the weak; it’s the imagined violence of the weak against the strong which justifies massive retaliation.”

There’s some truth to this: Nietzsche wrote persuasively about how Judeo-Christian religion is pervaded by a doctrine of *ressentiment* based on the envy of weak nations toward strong nations, as we see in the Old Testament’s frequent fulminations against Egypt and Babylon. Still, I wouldn’t see it as having much relation to “bullying.” Retaliatory force, sure; the avenging of perceived wrongs. But the very idea of a bully implies a disparity of force. Cue Merriam Webster:

bully (verb): to frighten, hurt, or threaten (a smaller or weaker person)

You could say that some strong nations choose to cast themselves as being victimized by weaker nations– in recent years, Russia vs. Ukraine– and use the supposed infringements as an excuse for retaliatory force. But I’m not sure the stronger nations have the emotional motives of the classic bully. Maybe you could class them as related to the “tribute-bully:” as long as you give him your lunch money, he’ll leave you alone. The classic bully, though, wants to beat someone weaker because he gets a sadistic thrill out of it. That seems to be what Wertham has in mind– he doesn’t devote a lot of space to geopolitical repercussions, as you do. So I don’t think the comparison applies across the board, though there may be some special cases where the stronger nation really enjoys the hell out of beating the weaker nation’s ass.

“I’d also say that the fantasy (or recognition, whichever you prefer) that evil exists, and the narrative fascination of confronting that without complication, tends to be the rationale behind huge outpourings of violence in history.”

But the motive of the violence in history is inextricably tied to that of gain, while the narrative fascination of avenging violence in fiction is a form of non-productive pleasure. In most cases the foot-soldiers in real wars don’t really have that much to gain, and everything to lose. But they often THINK their lives will be better if they win. Much ink has been spilled over whether the American South fought the Civil War over slavery or states’ rights. I propose a third alternative: the South did want an unpaid underclass, all right, but they also wanted to have that underclass count for them in the determination of legislative representation, as simple unpaid work-animals never could. Wanting to have your cake and eat it too would seem to me the very definition of a gain-oriented mentality.

“Incidentally, Jane Austen recognizes the existence of evil. But she doesn’t write stories where the pleasure is the fantasy of defeating evil without complications such as law, or morality, or worrying about the evil-doers humanity.”

Sure, but Austen is writing a different type of fiction; one where the problem of evil manifests in a civilized setting. Moore and Marsten are both invoking the spectre of retributive justice, just like Siegel and Shuster, but Moore does it for satire and Marston has a sociocultural agenda to promote. Apples and oranges.

Nope. Apples and different apples.

Why do you assume Siegel and Shuster don’t have a sociocultural agenda? They’re pretty clearly pushing socialism, and they were pro-America, pro-New Deal, and pro-intervention. That’s a sociocultural agenda. As is retributive justice as some sort of ideal.

Oh, and saying violence in history is tied to gain is confused. The Nazis had some motives for gain (they plundered Jewish wealth), but ultimately the resources devoted to the killings were probably counter-productive, and certainly by the end of the war they were murdering people just to murder them, out of confused hatred and panic.

Rather than just going over a lot of separate points, leave us return to the original disagreement.

You said that Superman was less good than Austen’s Darcy. I found that view insupportable, unless one chose to interpret the superhero’s deeds the way Doc Wertham did: as indicative of “something else.”

Now you’ve said here and elsewhere that you agree with Wertham that homosexual content appeared in WONDER WOMAN, but not, presumably, with his condemnation of that content in a juvenile context. Here’s a partial quote of his best-known remarks on the Amazon:

“For boys, Wonder Woman is a frightening image. For girls she is a morbid ideal. Where Batman is anti-feminine, the attractive Wonder Woman and her counterparts are definitely anti-masculine. Wonder Woman has her own female following. They are all continuously being threatened, captured, almost put to death. There is a great deal of mutual rescuing, the same type of rescue fantasies as in Batman.”

Do you agree with Wertham that WONDER WOMAN is either “a morbid ideal” and/or “anti-masculine?”

If you do not– and obviously I suspect that you don’t, or I wouldn’t bring it up– how do you convince others that Wertham was mistaken, except via the practice of “close reading,” of examining in detail *exactly what is on the page.*

Bet you can see where I’m going with this.

Close reading? On the page? I mean, that’s one way to go, but you could also look at the rest of Marston’s writings.

Marston is actually quite anti-masculine in a lot of ways; I wouldn’t necessarily argue with Wertham about that. And I’d probably want to know exactly what he meant by “morbid ideal” — probably we’d disagree about what is morbid and what isn’t (I.e., he thinks lesbianism is sick and unhealthy, I don’t.) Doesn’t have anything to do with close reading. As I said, Wertham is basically right that Wonder Woman is lesbian propaganda, and intended as such.

As far being frightening to boys…lots of boys read her; my son loves the Marston/Peter WW. So I’d just say that if Wertham finds it frightening, that is his misfortune, but that doesn’t seem to be the case for most.

Re: Superman. Again, you don’t need to interpret it as “something else.” You can just say, the ideals that Superman seems to express (the triumph of violence in the name of an uncomplicated good) is actually not an ideal, but an evil. You could also point out to the textual manner in which Superman treats Lois (not well) or point out that extra-judicial violence is bullying and not good, by most definitions.

You seem to think that if you don’t accept the ideals of the comic at absolute face value, or if you question the basic tenets of the ideology presented, then you’re somehow arguing for some sort of subconscious or buried reading. I don’t think that’s the case.

In other words, you’re saying that your only rejoinder to Marston is to say, “I don’t agree with your interpretation,” rather than trying to prove false logic on his part. Anything to avoid close reading, eh?

You’re missing part of the quote, too. Wertham doesn’t just say that WW is lesbian propaganda, he specifically says it’s “anti-masculine,” as if Marston were kissing cousins with Valerie Solanas. Not, I emphasize, just a “critique of masculinism,” in other words, but taking a philosophical position that despises all things masculine.

It’s my contention that *you* are the one interpreting Superman as “something else” when you resort to superimposing the morals of the stories with your own. Few if any of your comments about his dickishness can be justified from the context of the stories. If you just don’t like the character of the S&S Superman, that’s fine, that’s a matter of taste. But you didn’t state “Superman is not a good person” as an expression of your personal taste.

I might understand your queasiness about “extra-judicial violence” if we were frequently seeing Superman descending on African villages to make the natives obey the colonial powers. But Superman’s first heroic deed in ACTION #1 is to prevent an act of bullying, beating down a man who is beating his wife (can’t remember if the text calls her that or not). Yet in your view Superman becomes a bully even when he stops bullying. How many real-life bullies do that– unless, of course, it’s for some ulterior motive?

I don’t buy your objection to vigilantism because you’re applying it only to narratives you don’t like for whatever reason. Wonder Woman is just as much a vigilante as Superman; she acts with no authority save that of the goddess Aphrodite, whom I suspect would be considered extra-legal in American courts. Any number of WW stories have scenes in which WW slaps down bully-boys with the same ease that Superman does, so is she a bully? Is she therefore “not good” for the same reasons? Or does she get a pass because you agree with Marston’s politics?

I don’t say accept the ideals of the comic at face value. But critics should at least ground their extrapolations in the words and pictures on the page, rather than imposing upon them ideologies that bear no relationship to the original work.

“But you didn’t state “Superman is not a good person” as an expression of your personal taste.”

Oh good grief. Now I have to hold your hand and explain to you that opinions about art are opinions? Get a grip.

If you want to know what I think about WW’s vigilantism, you could read my book, out next year. I talk about her relationship to violence at great length. It’s not all good, but I think Marston does pretty interesting things with it. In this particular context, I think it’s not exactly right to call WW vigilantism; Marston is actually really careful to ground her authority in a legal hierarchy (starting with Aphrodite and going to Hippolyte.) It’s quite different from most superhero narratives in that sense; it’s really not about individuals taking the law into their own hand, but about the imposition of a separate, more loving law. You could argue about whether that’s better or worse (Charles Reece would say worse, I think) but it’s not the same as Superman. Saying it is suggests that you’re being (ahem) inattentive to the text.

Marston is pretty anti-masculine. He doesn’t just critique masculinity; he thinks it’s dangerous and that it needs to be subordinate to femininity. He’s pretty explicit about it. Your interpolation of Valerie Solanis is again not attentive to the text; there are various ways to be anti-masculine, and Marston’s is quite different from Solanis’ — and indeed from most second wave feminism. Again, I talk at some length in my book about how Marston is similar to and different from second wave feminism. So, again, I’d urge you to read it when it comes out, if you’re interested.

I don’t really know what you mean by superimposing my own morals? I look at the text, and I relate it to what I see as moral actions, and then I talk about that. You think that’s illegitimate because…your morals are better? Superman is old and therefore it can’t possibly speak to us, so thinking about it in light of my own standards and thoughts is illegitimate? I come to different conclusions than you do? Some combination? I don’t know…your insistence on close reading seems goofily naive, and the claim that close reading will lead you to the one truth seems like some sort of bizarre offshoot of evangelical logic. Words and pictures are both polysemic. Frustrating, I know, but there it is.

As I mentioned before, bullying is often excused or rationalized by presenting the other guy as the bully. Hitler does this with the Jews; it’s always the other person who is evil/has the power. It’s a pretty constant trope in both political narratives and pulp.

So you’re saying that you did sit down and examine the various ways Wonder Woman utilizes violence. Okay, then that would be close reading. But when you conflate Superman’s extra-legal action with bullying because “it’s a pretty constant trope in both political narratives and pulp,” that’s merely superimposing a pattern without close reading. It’s not naive to expect any critic to “show his proof,” and I haven’t said Word One about any One Truth.

I repeat: Aphrodite has no standing in American courts, so Wonder Woman’s actions are no less vigilantism than any other superhero’s, unless he is at some point given legal standing– which is eventually extended to Superman, though that may have occurred after Siegel and Shuster were dismissed. If you want to talk about tropes in political narratives– how about vigilantes claiming to act on the will of a deity?

I have no problem with polysemy; I do it all the time. But if you don’t ground your statements in the specifics of the text, then it’s just rhetoric. And rhetoric isn’t polysemous. It has just one essential meaning: “us against them.”

But Wonder Woman is a subject of Aphrodite, not the U.S. — and a good percentage of her adventures take place on places like Pluto…so…

Like I said, I’m not saying you can’t find problems with WW ideologically. If you find religion especially terrible or what have you, then yes, you can claim to have problems there. I’m just saying that WW and Superman are quite different in their treatment of violence and their approach to vigilantism. You said otherwise because you weren’t reading closely enough. You have now apparently come around to my view, so I’m pleased I’ve won that argument.

And rhetoric is polysemous, sorry.

Since this is pretty much how all the arguments end, this one may as well end the same way.

Fair enough! It was fun chatting with you; thanks for stopping by.

By the way, here’s my take on who gave who crap in the Superman-Lois interaction:

http://arche-arc.blogspot.com/2014/10/boola-boola-bouleversement-pt-1.html