In the beginning, R. Crumb created comics. I didn’t know this was the Word until I went to the Comics: Philosophy & Practice conference in 2012. I just sort of assumed that Art Spiegelman had created comics. Now I know that’s just in academia.

That conference was enormously interesting, but two things particularly stood out to me. The first was that Spiegelman, who was billed as the keynote speaker, transformed his speech into a dialogue with a prominent professor of media. “This was going to be a talk by me but I was too daunted by the audience of fifteen or sixteen peers who were billed as being here with me,” he said. “I couldn’t make myself deliver something that’s called a keynote address.” This was clearly a last-minute change; it wasn’t noted in the program.

Perhaps Spiegelman was just being modest, but on another level, he was absolutely correct: he was not the leader in that room. Over the course of that weekend, it wasn’t Spiegelman’s name that I heard praised again and again and again; it was Crumb’s. It was almost as though people took turns speaking to his influence. As thoughtful artists like Joe Sacco and Alison Bechdel paid him eloquent tribute, Crumb shouted stray observations from the audience like someone’s drunken uncle. I idly wondered if he was dying.

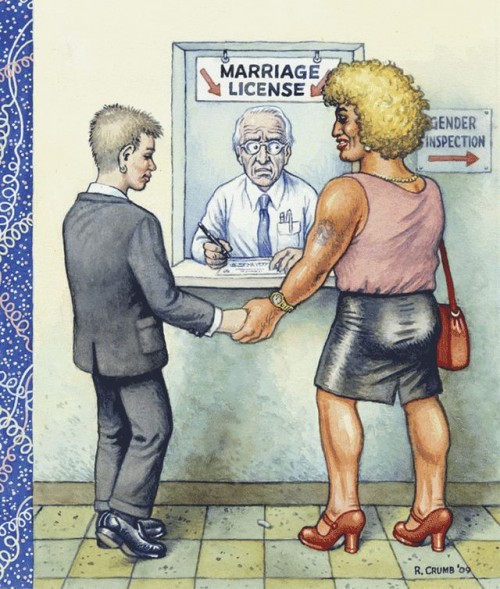

The second interesting thing was a disagreement that Crumb had with Françoise Mouly about his blown cover for The New Yorker. Mouly explained why the magazine rejected the art: it felt out of touch. But this is not the critique that Crumb heard; he preferred to cast himself as a provocateur. “I just realized that you have this loyal readership there that is pretty fucking square,” he said. “When you work for The New Yorker…you have to kind of bend whatever lurid qualities your work might have to fit that sort of lite, L-I-T-E [mentality].”

Characteristically, he was a real jerk about it. But what was most fascinating to me in looking at the cover (which Mouly had projected onto a huge screen) was that it was totally dumb. It had the unique distinction of being heavy-handed without actually making much sense—exactly the kind of “political” work you might expect from an artist who built an empire on drawing his dick.

It’s one thing to feel agnostic towards other people’s god; it’s quite another to find him ridiculous. Crumb’s affectations, his attitude towards women, his dim take on race—I don’t intend to spend a single second of this wild and precious life trying to figure out what other people see in that. Does that mean I’ll never understand comics? The answer is, simply, I don’t care, but I worry that’s arrogant. And on another level still, I feel resentful of that worry.

I find that writing, like life, is a delicate balance of feeling worried and giving zero fucks.

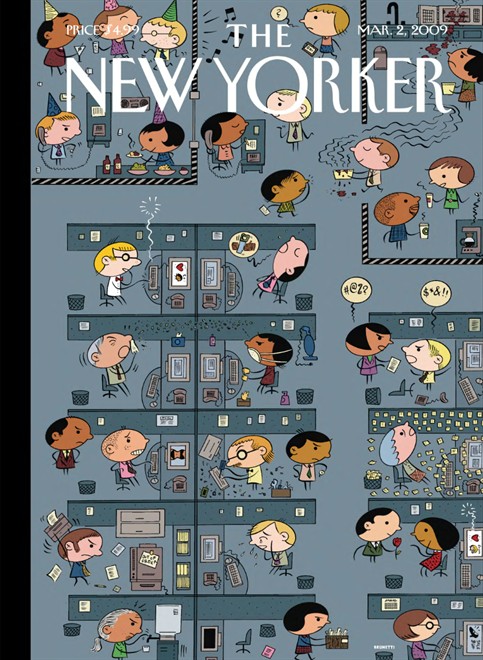

I like paradox. It’s the engine that powers everything interesting. When I started reading comics in a critical capacity, I was startled by the early work of Ivan Brunetti, whose illustrations I had seen in The New Yorker and Real Simple for many years. I hated Misery Loves Comedy. It was nothing like his work I knew and loved. But knowing the same man drew all of those things made me feel very hopeful about the world, where all too often people are afraid to embrace multiplicity. Now I scan every issue of Real Simple hopefully for allusions to murder-suicide. This brings me great joy.

There is a certain type of discourse—or is it a pedigree?—that is highly valued in comics crit. Names of the founding fathers (and let’s face it: it’s always the fathers) are whispered with reverence as a sort of password into that clubhouse. There is also a tendency to value historical perspective over any discussion of the present. Creating a false opposition between then and now (or high and low or this and that) is often done in the name of historical preservation, but it’s always a matter of propagating an opinion. There is no such thing as objective criticism; it is always an extension of the self and what you care about. There is an important distinction between saying these are the things that matter and saying these are the things that matter to me.

Still, some take a cold approach. They equate getting good with growing calloused. They forget that sensitivity is a tool, not a flaw. Men who learn to use that tool are generally praised. Sensitive women are crazy or inexperienced. We’re confused. We OVERREACT. Or so we’re told.

When I wrote the Piece that Shall Remain Nameless, I knew I’d be told all of those things. I felt a lot of doubt. I knew it would take fire that was far more intentional than the smoke the piece itself described. I thought that speaking up was the right thing to do. Now I’m not sure. I never am.

(I give zero fucks. I give zero fucks.)

I closely read a very small amount of material, not because it was in itself momentous, or to catch anyone in a word trap, but to explain how I felt about it, and also how I felt about something larger. The feelings were instantaneous when I read the material; the close reading came later. In response, people closely read my writing back to me. They called it fair, but I would argue it was not in the same spirit as the one in which I approached the project. So it goes.

There’s no one path to understanding. We go about it in different ways, if we go about it at all. In examining an issue from different points of view, it’s necessary to be critical of another vantage. But it’s equally necessary to interrogate your own.

R. Crumb created comics, and it seems to me that comics crit was then made in his image. I see his bad attitude and rude behavior all over this town. I see his petulance and his defensive posturing. I see his unwillingness to absorb a critique. And I also see his growing irrelevance—perhaps most keenly every time another fanboy tries to foist his opinion on the world under the noble guise of History.

Real criticism thrives in doubt, not in certainty. In conversations about comics, there is no right and wrong. There is only coming correct. Under the rock of my lousy long essay, it seems to me that a few people tried. Many others came to conquer. The anxiety of it, as ever, is women’s work.

I’d never seen that R. Crumb cover. I can see why it got rejected; I think Crumb is trying to make fun of the discomfort with gay marriage (?) but it seems to present a lot of discomfort itself, as well as sort of dumping the trans woman or drag queen) into Crumb’s default fetishes. The joke is that people aren’t gender conforming — which as Mouly says, seems fairly clueless at this stage.

I think the line from Crumb to comics criticism is classic TCJ. He was definitely a critical touchstone for Gary Groth, both in the sense that his art was seen as the ideal, or the greatest achievement of comics, and in the sense that Groth’s rudeness, his distrust of academia, and his disinterest in engaging with gender issues come from, or are at least in line with, Crumb.

Well, Crumb dropped out of that fairly early in favour of I – I – I.

Incidentally that New Yorker cover looks as if he took the commission to do a cover on the theme of gay marriage and then found he had no real opinion on the subject.

Kim, I’m surprised that you don’t register more similarities between Crumb and yourself — or between Crumb’s work (and his vision of his own work) and your own.

In both, there’s a premium on deep authentic reaction — to making one’s art (comics/criticism) both inevitably “personal” and personally ineluctable — traced back to scenes of rejection or resentment. You both seem to view your creations as things that have to come out, even if it invites hate from the fan-boys on one hand and middlebrow squares on the other. Your art — O’Connor’s and Crumb’s — is performance art, where to react to the text is to react to the person. And criticism is taken as such: an all-out affront. What would Crumb’s aesthetic mantra be if not, “I give zero fucks”?

I present this catalog not as criticism, but in the spirit of paradox. Or as one of my teachers once said to me, “When you come across a work of art that you can’t stand, perhaps begin by asking yourself what this might say about your needs and weaknesses as a reader.” Of course, that is only a first step, but I would like to talk more about your struggles, if any with Crumb. After all, your Brunetti-paradox is, for many, our Crumb-conundrum.

Joe and Noah,

I think you are right about Crumb and his cover. It is formally moribund and conceptually empty. There’s just nothing there.

Unfortunately for Crumb — but fortunately for us, perhaps — it’s a emptiness that falls on the wrong side of this particular cultural transformation. New Yorker readers want their emptiness a bit more treacly, with a dollop of self-congratulation.

Funny, I am not a big fan of Crumb – though I do find his art weirdly fascinating and think his Illustrated Genesis is fairly brilliant – mostly it is his “dim take on race” and attitude towards women as Kim puts it, but I do like that New Yorker cover.

I see the butt of the joke as the clerk, not the couple. Crumb is trying to illustrate the fluidity of gender, and the clerk’s expression shows that his doubt is his issue not gender identities (whatever they might be) of the couple who want to get married. Visually, it is like Crumb subverting Rockwell. It may not be as challenging as it could be, but for the square audience of the New Yorker (another thing I guess I agree with Crumb about) it seems to hit the right tonal mark to make THEM feel uncomfortable.

All that being said, if I were at a conference where either Crumb OR Spiegelman were the be and end all of comics, I would be pretty fucking miserable.

Hi Osvaldo,

I was there (I WAS THERE!), and I didn’t come away with that sense at all, except to the extent that Crumb was often the grouchy voice from the audience — sometimes matched by Lynda Barry’s “Oh Shut the fuck up” outbursts. Overall, Crumb came across as funny and (like almost all cartoonists) self-effacing, if in a humblebrag sort of way. Heck, he even sang!

Regarding Crumb, race, and gender, I think you are right to hint that GENESIS offers a lot to say about those topics, even if one only attends to Crumb’s own comments about the stories’ women characters, the loss of matriarchy, and Jewishness.

Can people tell that the cover is of a man and woman getting married?

It’s not clear from a lot of these “that’s dumb,” “that’s homophobic” reactions.

New Yorker covers often go for that double-take, hidden gag…

Hey Ryusu. Sure, I can tell. It’s setting up a dichotomy between trans people, or cross-dressers, and gay marriage.

The joke still kind of comes off to me as, “aren’t queer people funny/awesomely deviant?” Which, yeah, I still think is dumb.

I don’t see how it sets up any such dichotomy.

It’s sort of a gay/not gay marriage. Or “queer,” if you embrace the universalizing of the term.

The point is to render the distinctions meaningless.

Is it? Or is the point to render human beings as a sight gag?

I’m a little surprised by everyone’s reaction to the Crumb cover, I don’t see it as homophobic at all, the joke is clearly the straight laced clerk’s reaction and the idea of a “gender inspection” room. He’s highlighting the absurdity of the idea that gender has anything to do with love or marriage.

Crumb said about the cover

“There are guys who’ve had their dicks cut off, and girls who’ve had them added on, so the idea of a gender cirterion for marriage is ridiculous.”

(source: http://assets.vice.com/content-images/contentimage/no-slug/7e6242f4d5b427fd327b7cbb000e1f49.jpg)

Now Crumb’s being far from pc by referring to trans people that way, and I don’t doubt a lot of people will find that offensive, but Crumb’s whole thing has always been to write without filtering himself and he’s a crass and rude person. If it had been framed as just “gender isn’t binary and permenant so having is as a criteria for marriage is ridiculous” which I don’t think anyone would be offended. The issue with much of Crumb’s work seems to be in his language (both in drawing and writing) having a lot of stuff that people consider offensive by general consensus, rather than actually being offensive in ideology. That said he undeniably has a lot of issues with women and different races, which do not appear as subversive as they once did because there’s not the same repression put upon those issues which he was bringing to the surface as their once was.

The idea that you can easily separate ideology and language, in Crumb and in general, is pretty problematic.

Crumb’s response to criticism is often, well, I’m not filtering myself. But is that really an excuse, or a way around, racism or sexism? I don’t see how it is, exactly. Reproducing racism or sexism or homophobia as a kind of sign of the authenticity of the self and one’s own fearlessness seems pretty repulsive to me. If you care about these issues, why not think about them in an effort to deal with them in an intelligent way? And if you don’t bother enough to think about how not to be racist, well, then you end up being racist. Sorry.

I think the classic TCJ view of Crumb’s work as the greatest achievement in comics is echoed by most “art comics” cartoonists, though. The majority of artists mentioned in Kim O’Connor’s autobiographical cartoonists piece would probably cite him as their main influence. But there is something a bit weird about canonizing Crumb, who hates everything about the modern world (including pop culture, the art world, and academia) and enjoys pissing people off.

I’m talking about language in terms of the way that words like “retard”,”queer”, or “coloured” have had their acceptability changed, I think that Chrumb often uses the kind of language we associate with old fashioned or offensive opinions even when he’s saying things which are not offensive.

Whilst I don’t think the New Yorker piece is offensive, I’m not going to defend everything Crumb has ever done, because I am not that much of a fan of his work, but his own reasoning for a lot of the stuff he does which is considered offensive is to “bring to the surface the underlying cancer which is in all of us”.

I’m curious because I didn’t even consider that when I looked at it, do people find this image offensive because they think the drag queen character is parodic or a point of ridicule? If they think that, why do you read it that way?

I am pretty sure I’m with Noah here, but not so much in reaction to Crumb’s ideas – or at least not only in reaction to his ideas. I think part of the problem with the cover has to do with Crumb bumping up against the limits of his own ability as an artist. It might be difficult for any cartoonist to represent a trans-woman (or man) without representing, in some legible way, the “gap” between the character’s assigned sex/gender and her assumed/chosen gender. That is, the gap between the man she was and the woman she is. After all, without that gap, the character would just read as “woman.” And the joke — the problem of misidentification — would fall silent, since there would be no problem. The cartoon would only show “one” thing, not “two.”

Of course, there are ways this could be achieved — this “uncomfortable” ambiguity — but it would require, in a sense, going against some of the habits of cartooning and iconographic representation. It would require some… subtlety. And Crumb’s style does not easily access this level of subtlety, in part because of of the old cartoony, grotesque forms of showing us stuff. He only has one way of showing a trans-woman, and that is as a beefy guy with an overdone wig. (Think of this as the visual, cartoony version of the distinction between “dick” and “no dick.”)

I agree that Crumb wanted to go for discomfort and the undermining of “gender ID” here. But he is unable to pull it off. His style only allows him to show us one thing.

(Typed on a phone. Sorry for any incoherence.)

Peter

How do we know that the couple isn’t conducting a kind of protest? Is that a reasonable reading?

Walpole: Give me a fucking break.

“It might be difficult for any cartoonist to represent a trans-woman (or man) without representing, in some legible way, the “gap” between the character’s assigned sex/gender and her assumed/chosen gender.”

There is such a thing as trans cartoonists.

Michael, you misunderstand my point. If it applies, it applies to trans cartoonists as well (although such cartoonists would likely be more sensitive to and fluent in the realms of representation). Nonetheless, the question persists: how does one visually represent the “trans” in transwoman? Stipulating the gender identity of the artist doesn’t solve or dissolve it.

trans cartoonists don’t have to conform their work to suit your gaze which apparently MUST distinguish them

Bumping against limits of the medium: an illustration can’t clearly register a cross-dressing man without using gender signifiers or a very masculine physique. The point of successful cross-dressing is ambiguity. But that doesn’t work against the goal of this illustration, which is to mix up gender signifiers, not create androgynous characters. Notice that the woman gets an earring, which doesn’t go with the gag… but if she didn’t, that character would register as a youthful boy. That’s not a matter of illustrative competence, that’s nature.

Ryusu you have no. idea. what. you. are. talking. about. Both in terms of cartooning and discussing gender non-conforming people.

Michael, of course they don’t. Who said they did? But if any cartoonist wants to represent a transwoman who is identifiable AS as transwoman, then he or she must devise a way of making that identity visible/legible. If the artist doesn’t care about making that character “trans” identity visible, that’s her business.

I think it’s nice that Michael’s here yelling at people, being angry and offended without contributing anything. It is great and is raising the level of discourse on this website. I can only imagine the heights of illumination and transcendent genius he would reveal to us all if he wrote a comment where he explained any of his opinions, didn’t just bash someone else, or wrote a comment which is more than four lines long.

Michael, I’m saying there are kinds of cartooning that rely on clearly communicating information. If you’re trying to clearly indicate that a character is a man dressed as a woman, you’re going to rely on gender signifiers or an unambiguously masculine physique. What else would you do? But if you’re going for ambiguity, that’s not necessary.

As for my comment about “successful” cross-dressing, I guess I should have said “passing?”

I try to use the right terms when I know what they are, and I try not to offend people unnecessarily, but a lot of the back and forth I see on the internet about race, gender or sexuality adds up to assertions that you don’t have the right to express an opinion about this, this is not your turf. And yeah, OK, my qualifications are a couple of friends, watching Rupaul’s Drag Race, and drawing stupid pictures (not on this subject, though).

I don’t think the goal of this image is to comment on the transgender community. I think it’s mixing masculine and feminine traits in a scenario that asks why gender is so important to marriage. That the effort to nail down these categories is absurd.

Do you feel that a character that is clearly a man dressed as a woman—even flaunting that—is inherently offensive?

Ryusu: Depicting trans and gender non-conforming people is more complicated. It’s best to refer to how trans people draw themselves FIRST before referring to visual traditions that are rooted directly in tropes that are designed specifically to dehumanize, ridicule and undermine trans people, which this crumb drawing cleeeeeaaaarly is utilizing. If his gag doesn’t make sense without using these offensive stereotypes, it is an offensive gag that assumes an offensive mindset in order to work.

I am gender non-conforming in my dress, and my goal is NEITHER ambiguity or passing. I dress to feel comfortable and please myself, period. I’m not “cross-dressing,” i’m just dressing.

Drag Race covers a very narrow aspect of Drag culture and Drag as performance is not a reliable reference for the actual day to day lives of trans or non-conforming people in general.

There is a way to communicate that gender oughtn’t matter in a civilized society, and this crumb drawing ain’t it. It’s clumsy and disingenuous, and revels in ugliness, as if to say in resignation “these freaks are all over the place, whacha gonna do?” I see the clerk, rather than being the butt of the joke, as being a stand-in for Crumb himself, who hates modernity as much as any other ol “square.”

Your last point, is a character depicted as “clearly a man dressed as a woman” offensive: yes yes yes yes yes yes yes yes yes. Even your choice of words… “flaunting” is not a word queer people generally adopt to refer to ourselves and folks like us. It’s usually a negative assessment of our character imposed on us by straight folks. Language has meaning, images have meaning. Language and images with a history of bigotry don’t exist in a vaccuum.

I understand your feelings of being shut out of a conversation, and I apologize if I sound a little short with you. But we need to get up to speed with the language we use in our criticism.

Whoops; I was offline for a bit, or I would have weighed in earlier.

I agree with Michael pretty much; I read the marriage license guy as a Crumb stand in. The drag queen (which seems to be what Crumb feels he’s depicting) is represented in a pretty offensive and stereotypical manner; she’s also sexualized in a way I generally associate with Crumb’s women (lots of focus on the rear), which is a fairly typical way in which trans women are stigmatized; that is, they’re denigrated for not being female enough while being insistently sexualized in a misogynist way. As Peter suggests, the reason Crumb “has” to do this is because the “joke” is precisely in the legibility of the gender wrongness; the joke of the piece is that it’s funny that there are people who don’t present with the sort of gender Crumb views as normal. Which isn’t much of a joke unless you’re kind of an asshole, I would say. Which Crumb is.

It’s kind of a good example of why the excuse that he’s just dumping out what’s in his head isn’t very convincing. What’s in his head is pretty boring, staid, and offensive stereotypes about what is and isn’t normal in terms of gender presentation. It’s the equivalent of somebody half-drunk belching and coming out with, “I know this isn’t PC…but drag queens are really something, huh? No offense, but those folks are weird!” Except that Crumb goes on to claim that babbling ignorantly like that somehow makes him an artist because he’s honest.

Edie Fake is the trans cartoonist I’m most familiar with, an his work is really visionary and amazing and beautiful. He approaches gender in insightful and surprising and beautiful ways; his last series of works are these intensely patterned, fanciful visions of vanished Chicago LGBT spaces, which suggest quilts and video-games. If the New Yorker knew what they were doing, they would get him to do a cover for them. But they don’t. But at least they nixed Crumb’s piece of crap.

Oh my, I’d be fascinated to hear more about what disliking Crumb says about my needs and weaknesses.

Just kidding. Anyway, I don’t regard this essay as borne out of rejection or something that “just had to come out.” This essay is about, among other things, the strange and persistent myth of objectivity in criticism…which is particularly ironic in comics crit, which very often comes from a place of deep fandom.

Giving zero fucks when it comes to how something will be received by an audience can mean different things, I guess. For women, the stakes of critical reception are often different/heightened. For a ready example, compare the tone and content of critiques from the most outspoken detractors of Robert with those of Aline Kominsky-Crumb and get back to me on gender disparity in where the line is drawn between reacting to a text and reacting to a person.

The myth of objectivity in criticism and the critical reception of women’s work are separate issues, but they often intersect. Dollars to donuts, Aline’s most vocal critics would say their insults are rooted in their sincere belief that Robert’s work is objectively superior to hers.

I gather that many people see Crumb as artistically brave. But there is a pronounced difference between giving zero fucks and simply not giving a shit. The latter is sort of an absurd mode for political commentary, and yet Crumb persists in trying to make it. If he can be called clever, it is only in how he has conveniently situated himself in a paradigm in which he’s incapable of doing anything wrong.

The thing is, Crumb’s offensiveness is not “bring[ing] to the surface the underlying cancer which is in all of us.” Racism, sexism, homophobia etc. is not intrinsic. It is learned. And so far as I can tell, Crumb more or less perpetuates it.

Thanks for writing this, Kim.

“The latter is sort of an absurd mode for political commentary, and yet Crumb persists in trying to make it.”

It’s often hard for me to figure out why Crumb makes the choices he does. Why illustrate all of Genesis when you don’t appear to have anything to say about Genesis? Why do a cover about gay marriage when (apparently) you have little if any interest in gay marriage? I feel like that about much of his work, with the possible exception of his more sexual comics. For a cartoonist who is supposed to be so confessional, he often seems really disconnected and disinterested.

his disconnectedness is his safety net from responsibility, he can’t ever give it up

Hi Kim,

Thanks for taking the “needs and weaknesses” stuff with a block of salt. I’ve got nothing to say about it. It was some advice a teacher once gave me — although I think that she may have talked about my “character” as well as my tastes.

Nonetheless, it seems that the insight behind my mentor’s suggestion fits quite aptly into a view of criticism as completely subjective. To put it directly, if all criticism tells us about or represents is the critic, then it would seem to be a worthwhile activity to ask oneself, continually, why am I hating this? what am I not seeing? what does this tell me about me?

“Personal” criticism as a type of writing is not my thing, for instance. But wouldn’t it be one small step away from the “myth” of objectivity is I put my own distaste under the microscope as *part* of my critical project? Wouldn’t you want to perform your paradoxes — if only to avoid sounding as damn-sure as any objectivist?

Of course, all this is easy to preach from outside the church. Toss it is it’s trash.

One side question: are there really a lot of people out there bashing Aline Kominsky-Crumb? If anything, I think the greatest gender disparity regarding her work is that, until recently, no one talked about it at all. (Chute makes a similar point.) Indeed, the only person I can recall recently saying that AKC can’t draw is — and this is part of her shtick — AKC.

Peter

I think Crumb’s politics are pretty thoughtful and heartfelt. Just to go over some reoccurring themes… He’s pained by the replacement of folk cultures with corporate culture (“Where has it gone, the beautiful music of our grandparents?”) and the spread of urban ugliness (“A Short History of America” and his frequent telephone-pole-and-parking-lot-filled backgrounds). He views societies as naturally dominated by cruel, dumb macho men (“Cave Wimp,” “The Ruff-Tuff Cream Puffs Take Control,” and his strip about giving Donald Trump a swirly). He’s afraid that humanity will self-destruct through nuclear war or environmental degradation (“The Goose and the Gander Were Talking One Night” and some other stories). And he has a dim view of celebrity culture, as seen in his story about attending the Academy Awards and feeling embarrassed for all of humanity while slinking across the red carpet. At any rate, I think his political commentary is more substantial than Democrats vs. Republicans stuff and people Tweeting “Wow. Just wow,” in response to sexist/racist/homophobic comments by entertainers and politicians.

I agree that the New Yorker cover is banal, but I doubt he’d justify it by saying “I’m just exposing my warped inner psyche” (he does talk about it in the link Nathaniel Walpole provided). Maybe his motive for the cover and the Genesis book are that he’s in his 70s, losing some of his inspiration (as most artists do eventually), and casting about for something to do. I think he was pretty invested in most of his work through age 55 or so.

Hey Michael, thank you for taking the time to write. I was nodding along with a lot of your comments.

A general note re: some of the comments in this thread about exclusion. If you want to join a conversation, at least read a Wikipedia entry or something. Don’t just demand that other people in the conversation educate you on the basics. That’s really presumptuous.

Noah, didn’t Crumb do Genesis for the money? Feel like I’ve read that somewhere. IDK about his motivations, esp. the later stuff. The NYer cover obviously wasn’t for money. My impression is that he’s quite vested in his image as a bad boy…which is funny given his supposed interest in authenticity.

Peter, I dunno man. It seems unfair to act like I’m humorless for responding to your point…especially when you then simply reassert it. Let me ask you a question: why, after reading my explanation of why I don’t like Crumb, would you then assume there’s some other deeper subconscious reason that I don’t like Crumb? If your own criticism isn’t very personal, maybe you should ask yourself what is up with your somewhat psychoanalytic perspective on this essay here in the comments. I’m not being snarky; I am genuinely perplexed.

To clarify I’m not trying to say that every act of criticism is some pure burning act of the soul. I just think in criticism (and this isn’t *just* in comics) there is often a pretense of objectivity that is weird. I feel the same way about journalism. And I think that in both criticism and journalism, practitioners should be aware of their own subjectivity even if they don’t choose to foreground it in their work.

Anyway I think you’re absolutely right that AKC hasn’t gotten that much critical attention and that she makes fun of her own drawing. But in my interview with her years ago, and others I’ve read (including one with Chute), she has talked about the super misogynistic comments she has received (and comments about her that Crumb received) from his fans over the years.

Jack, with all due respect–especially because we’re getting into territory that I’m obviously not really familiar with–the political themes you discuss sound to me like a general sense of nostalgia, cynicism, and generalized resentment toward The Man. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, but it doesn’t sound all that thoughtful.

Walpole: If you want me to be your nanny and tuck you into bed, you can’t afford me.

Michael, you know full well that’s not what I’m saying, I was annoyed that your contribution to the discussion was just dismissal and brow beating. It would be one thing if people were being actively hateful or had responded with anything besides surprise that something was read as transphobic or homophobic when they had not read them that way. I mean I’m sure your criticism is fine and great and all, but you just seemed like an asshole.

When you actually commented in some length, I thought about it and I actually agree with you, whilst I still think the intended butt of the joke is the clerk and how gender is fairly meaningless, the shorthand that Crumb uses for trans people is still offensive (which is what I meant by the distance between language and ideology). I think the reason I didn’t find it initially offensive is that I have met guys who are fairly masculine and gender identify as male, but also enjoy enjoy wearing womens clothes, and that’s what I read the representation as. Someone who was outwardly male, but just enjoyed crossdressing, if you do read it as that being Crumbs idea of what a trans person looks like then yeah, it looks bad.

Hey Michael,

I wasn’t objecting based on any feelings of exclusion, and I’m not bothered by your tone. I just find the way a lot of these conversations go on the internet to be unsatisfying as argument.

Your answer as I understand it is that it’s ALWAYS offensive to portray a trans person as clearly a trans person using visual information alone, using a style of cartooning that relies on clear signifiers. (“Your last point, is a character depicted as “clearly a man dressed as a woman” offensive: yes yes yes yes yes yes yes yes yes.”) That’s the question I was asking you, anyway. Fair enough. If you can’t visually signify that, that renders my list of tools you could use moot, and it means the subject demands a visual ambiguity. That’s the ambiguity I was referring to with my comment about cross-dressing/passing. I wasn’t talking about the reason a person gets up and does it in the morning, and I apologize for not making that clear.

I’ve never felt that any gay or trans person was “flaunting” themselves at me, in the sense that their self-expression was any kind of gauntlet thrown down. I was describing a style of playing up a mix of masculine and feminine traits as opposed to playing one or the other down, for a related question as to whether that is also necessarily offensive.

My list of “qualifications” was intended to be self-evidently absurd.

Re: your and Noah’s reading of the cartoon. Both of you place Crumb in the cartoon as that guy sitting in the booth. That’s pure speculation, but how would that reading go? Crumb wanted to express his feelings that cross-dressing people are weird and they make him uncomfortable, and to express his hostility toward marriage equality. The cartoon doesn’t communicate that to me. What I see is a cartoon set in a regime of strict gender requirements for marriage. A cross-dressing couple shows up and freaks the clerk out, when in fact they’re a heterosexual couple who are entitled to marry under that regime. The joke is on the clerk. So is Crumb saying, “I’m that clerk, and I can’t tell what gender people are these days. I feel that I’m being made a fool of!” No, I think the clerk is a stereotypically conservative old dude who is maintaining an absurd bureaucracy. This is why I don’t find “the artist is that guy” readings very satisfying.

NOAH: “The drag queen (which seems to be what Crumb feels he’s depicting) is represented in a pretty offensive and stereotypical manner; she’s also sexualized in a way I generally associate with Crumb’s women (lots of focus on the rear), which is a fairly typical way in which trans women are stigmatized; that is, they’re denigrated for not being female enough while being insistently sexualized in a misogynist way. As Peter suggests, the reason Crumb “has” to do this is because the “joke” is precisely in the legibility of the gender wrongness; the joke of the piece is that it’s funny that there are people who don’t present with the sort of gender Crumb views as normal.”

The groom in the picture doesn’t look like any kind of cross-dressing person or drag queen I’ve ever seen. He looks more like a fraternity dude on one of those occasions where they decide it’s funny to dress in drag. Everything about him under the female clothing and makeup says masculine, even his stance, his size. The woman is being feminine, delicate, turning her foot. They’re conforming to gender stereotypes. It could be that the image steps too much on the toes of the transgender community and it doesn’t work for that reason. But I don’t think it represents Crumb taking on the phenomenon of all the non-gender-conforming people out there in the world: it’s taking on the gender criterion for marriage. It’s not setting up a dichotomy between gay and transgender people by posing a couple that would freak out conservatives but meet their criterion. It’s collapsing the criterion. “Hey, male and female couples don’t even feel male and female all the time either.” That’s also why I think it’s a fair interpretation, not necessary but possible, that the couple is staging a protest. Or are you only allowing for the bad kind of subtext and hidden meanings?

KIM: “A general note re: some of the comments in this thread about exclusion. If you want to join a conversation, at least read a Wikipedia entry or something. Don’t just demand that other people in the conversation educate you on the basics. That’s really presumptuous.”

Asking if there’s any acceptable way to communicate that a person is transgender using visual signifiers alone is presumptuous? In a comic book forum that discusses gender and sexuality? My comment was prompted by a phenomenon that I’ve seen on the internet, and here, in which people treat serious issues of race, gender and sexuality as a matter of turf and the right to express an opinion. In fact, I was thinking of your take on Spurgeon’s tweets, which didn’t seem to be an argument with what he was saying so much as his being a man expressing his opinion on a women’s issue. “I am the Grand Poobah of the comic book internet, etc.” I’m not complaining about being excluded from any conversation myself but pointing out a style of pulling rank instead of engaging with an argument. There was kind of a reductio ad absurdum of that style here a few years ago when a gay man wrote about how he felt about being represented in yaoi manga and got commenters throwing down with full-on, “you’re out of line, you don’t know our community, we already discussed these problems and settled them for all time” reactions.

“Jack, with all due respect–especially because we’re getting into territory that I’m obviously not really familiar with–the political themes you discuss sound to me like a general sense of nostalgia, cynicism, and generalized resentment toward The Man. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, but it doesn’t sound all that thoughtful.”

Could be, could be not, but I think the criticism was that Crumb suffered from a lack of interest and engagement. I don’t think that applies at all. “Where Has it Gone…” was a passionate story.

Where criticism is concerned (not just comics criticism), I think the problem is that Crumb is, like a lot of critics from his generation, at a convenient crossroads between modernism and post modernism. That is, he is suspicious of authority and claims that derive from it, but he can’t quite shake the idea that he hasn’t somehow earned his own authority, hence his tendency to bristle when people disagree with his verdict. I think this is a condition that afflicts even post-structural and self-reflexive critics, too, insofar as criticism is hard to do without a firm commitment to one’s interpretation of or view on a text, but some people seem more tied up in it than others.

I think the thought that has been put into analyzing this cover here in this thread is probably more than the thought that Crumb put into it when he was drawing it. I think Crumb may have been making a joke about the clerk, as in “Ha ha, look how freaked out this guy is!” but he’s also saying “Ha ha, look at these freaks!” and that latter part is what’s out of touch. If you’re trying to publish a piece about marriage equality, portraying the people who are fighting for that equality as a bunch of weirdos is one possible approach, but it’s presumably not the one that the New Yorker wants to take. So rejection, making them a bunch of squares who just don’t get him.

But really, my question is, what’s with the “Gender Inspection” sign on the wall? That’s a weird detail. It might be an additional joke about only heterosexual couples being allowed to be married, but it kind of makes the whole thing even more heavy-handed, with any laughs about freaks trying to get married undercut by the idea that they’re going to be strip-searched in order to make sure they have the right number of penises.

I think Genesis was just a project Crumb was interested in, and Pantheon was obviously excited to have Crumb’s first-ever graphic novel on its hands. He later joked that it was just a “straight illustration job”, but I believe he did it because of the challenge involved as well as wanting to illustrate just how filthy Genesis is.

I agree w/ the sentiment that the cover was meant to be pro-legalization. But stereotypical drag imagery is pretty much the last thing Crumb should have used to convey gender ambiguity, which is what he was aiming for, or at least claiming after the fact. (LOL that there are 1,000 different Vice defenses of this cover. Here’s the one I read before I wrote this: http://www.vice.com/read/the-gayest-story-ever-told-0000048-v18n11?Contentpage=-1) Anyway, one of the many reasons I think this cover is dumb is because of its focus on how people look (conform or don’t, pass or don’t, etc.), which isn’t really a salient issue in gay marriage.

Ryusu, my comment was not criticizing whatever you said about visual signifiers or whatever. It came from a place of seeing some uninformed arguments (among them one of yours about the goal of cross-dressing being to pass) floating around. Someone is not being the PC police if they express frustration with your false characterization of something. I don’t totally follow your turf war thing but I don’t think any of the comments in this thread have been proprietary.

I love R Crumb cause I prefer the hot’n’squishy pole of drawing rather than the cold, clean pole of Brunetti, Ware, Clowes, etc. I don’t see that women who go squishy are derided for it…. Yes, Bechdel and Satrapi are arguably on the colder end and are valourized, but so is, as mentioned above, Lynda Barry. You don’t get much squishier than that. And Carol Tyler, and Aline Kominsky, and Dame Darcy…..

I also enjoy R. Crumb because a lot of his fetishes do it for me. I thought as sex-positive feminists we all embrace non-PC role play now (which means of course that it’s equally valid to hate him for the same reason. It’s how I felt during all the Manara talk). He did have things to say in Genesis, even if you think those things weren’t smart. And to tie it back together, I liked to see him exercising his Jew fetish.

“I think this cover is dumb is because of its focus on how people look (conform or don’t, pass or don’t, etc.), which isn’t really a salient issue in gay marriage.”

Kim nails it here, at least with respect to the cover. After all, the situation on the cover could happen with a cisgendered couple so long as both parties are gender non-conforming in their dress.

However, I suspect that appearances are pretty central to gay marriage as an issue. In mainstream media (hi New Yorker) you’ll notice that the ideal gay couple is pictured along pretty heteronormative lines. In this respect, Crumb might be onto something when he cites square hang ups about appearances. Of course, as Michael, Kim and others note, if he is right, he’s right for all the wrong reasons.

!!! Miriam! Hey; so glad to have you comment. Hope you’re well!

Miriam was one of the first writers on this blog; she hasn’t stopped by in ages. I am pleased to see her here again.

All right, let me do what I thought I’d never do: defend Crumb.

Not so much to attribute any more thought or thoughtfulness to him, but in part to re-contextualize the over-the-top nature of the image and how it connects to Crumb’s work as a whole. (This is quite different than what I was saying before about Crumb’s limits, the border of the visible, and the challenges of visually representing a person as “trans”-anything.)

We already know that Crumb deals in sexual obsession, presenting people as drooling, ogling, squirting, lumpy, and — in the case of men — hairy beasts. That’s just his thing. Love, not so much. (Indeed, he presents love as a delusion, a cover, insisting that he’s never been in love himself.)

So one part of a Crumb image of “love” or “gender” or “marriage” or “family values” would almost necessarily reduce them to (or expose them as) veneers over the demands of the body.

This would go for EVERYONE.

Concerned about the sanctity of marriage? Your really just interested in what people do with their dicks and want to inspect them for said.

Do we celebrate marriage as a civil right? How is this any more than an institutional costume that tries to domesticate sexual impulses? (See “Joe Blow”)

Do you see yourself as gay or straight, a man or a woman, trans or cis? This, too, is a facade, as artificial and confining as formal attire or bad drag. Underneath, you are your body and what it wants — regardless of what you choose to do with it, dicks on or dicks off.

In a sense, then, the Crumb vision of “same-sex marriage” focused as much on the hypocrisies of “marriage” and “love” as it does on that of “homosexuality” or “transgenderedness.” It’s all about fucking. And perhaps the “perverse” couple, making the old man so nervous, are just more honest is their perversity, dragging our discomfort into the open.

This is not, to my mind, excusing Crumb. But it does place the image in the world that Crumb has been creating and exploring for the past 50 years, even in the hairy and sweaty Genesis. You may still think it’s an aesthetic dead-end or a political cesspool — or even just a tired one-note song — but I’m not sure that “so dumb” or “Heh! Queers are weird!” do it justice.

Crumb may not want to tell the story of same-sex marriage or gender that most of us want to tell. You can look to the rest of the awful New Yorker covers on the subject for that: all hazy, all smiles. But when has he ever?

Peter

P.S. One last thing. The Crumb cover seems to tread some of the same iffy ground as the “South Park” episode on the subject, where Mrs Garrison, after her sex-change operation, wants to put a halt to the Colorado gay-marriage initiative, so that Mr Slave and Big Gay Al cannot get married (and she, as a woman, can marry Mr Slave instead — in the normal, natural way). Both Park and Crumb don’t try to think to hard about comfortable representations or idealistic cultural intentions.

But I’m not a gig South park fan either

Kim: Ah, but that’s not what I said, nor would that make sense with the other things I said.

Listen, Ryusu, I realize that’s not what you meant. But I’m not going to apologize for giving the side eye to your original sentence, which was “The point of successful cross-dressing is ambiguity.” Highly doubt I’m the only person here who read it as wrongheaded. That’s not people combing your comments looking for language to object to. That’s objectionable language. I think that’s an important distinction.

Agree with Nate A in that appearance is a salient issue in gay representation (if not gay marriage). Which is one reason why using stereotyped imagery in an effort to “mix up” gender signifiers is super dumb.

Hey Miriam. I guess I’d say that I thought as feminists we’re not all doing anything. I don’t begrudge your right to like Crumb. I just think he’s intellectually lazy, and not particularly deserving of his “brave” reputation. But anyway I was talking about the cold/hot poles re: criticism (not cartooning).

“In a sense, then, the Crumb vision of “same-sex marriage” focused as much on the hypocrisies of “marriage” and “love” as it does on that of “homosexuality” or “transgenderedness.” It’s all about fucking. And perhaps the “perverse” couple, making the old man so nervous, are just more honest is their perversity, dragging our discomfort into the open.”

See, but using queer people’s bodies as a way to show the grotesqueness of sex or the artificiality of love; that’s leveraging stigma against gay people, right? It’s using the prejudice against gay people as a way to sneer at the bourgeoisie. I still have trouble seeing that as especially thoughtful.

Noah, I’m not sure it’s *especially* thoughtful either — just of a piece with how Crumb has reveled in the grotesqueness of suburban families, bodily fluids, urban landscapes, penises and vaginas, funny animals, and aging. His is a broad refusal to celebrate, or a celebration only of perversity writ large. Politics is always just a cover for sex.

Now perhaps he should not leverage existing stigmas and prejudices in this effort, particular again already burdened populations (perverse suburbanites, yes; perverse gays, no). But it would hard to say that Crumb is using a different language here or a different set of standards, and it *might* even be wrong to call those standards transphobic.

In that spirit, I can’t recall any Crumb comics presenting any gay (or anti-gay) stereotypes, can you? Not even when he might have used sexuality as a form of decadence, as in, say, Genesis. Perhaps it’s a problem that homosexuality is invisible, but he hasn’t used it as an easy target.

Last suggestion: the character in the cover who reads as “man in bad drag” actually, from the waist down, doesn’t seem all that different from a typical Crumbian fetish model. Those are just the types of shoes, calves, and ass that R.’s cartoon self would hump joyously.

“the character in the cover who reads as “man in bad drag” actually, from the waist down, doesn’t seem all that different from a typical Crumbian fetish model. ”

Yep. As I said earlier, sexual festishization of trans women is quite common. A big part of the stigma trans women face is misogyny, as Julia Serano argues quite convincingly.

I haven’t seen a lot of transphobia, but his use of invidious stereotypes to (supposedly) tweak the bourgeoisie is pretty consistent with the way he’s used black stereotypes in the past, I’d say.

“So one part of a Crumb image of “love” or “gender” or “marriage” or “family values” would almost necessarily reduce them to (or expose them as) veneers over the demands of the body.”

Crumb really is obsessed with surfaces, isn’t he? His work is all about bringing the inside to the outside, or to put it another way, making the inner life visible. This is an obsession he performs over and again- in his cartoons, in his dress, in his public persona (he will not, cannot, not talk). This is all well and good (if a little played out) when you’re doing a burlesque dialectical take-down of the antinomies inherent in the dominant perspective, but it doesn’t work very well when representing the excluded other, since it limits you to trafficking in the stereotype.

I think we’re edging towards consensus here, Noah — although perhaps only I am. I do think it matters that this is the sort of body that Crumb honestly lusts after, and that he’s not playing this joke (like many have) in the gotcha you-thought-is-was-a-hottie-but-it’s-really-a-dude way. Crumb takes his fetishes straight, no pun intended. In fact, for him, it’s not any more of a “fetish” than any other kind of attraction — something that I think Serano would appreciate, given hatred of the term.

OK, I think that’s it. The cover is not great, maybe not even good. Damn, I don’t even like it graphically! But after all this, I find myself appreciating its “lurid” vision more than many of the magazine’s other attempts to frame the issue, which I looked at once and rarely thought of again. Sweetness only gets me so far.

And all-thumbs-up for Miriam’s comment! Sorry I hadn’t read it before my last foray.

A last, last, last comment, this time linking to a nice little comic about, in part, the limits and limitations of representation when it comes to gender identity, sexuality, and trans-anything. Imagine it without the bottom caption, or with the caption’s terms reversed. Hope it ties to at least one thread of the discussion.

When The New Yorker at various intervals likes to round up its gay-themed covers for various self-congratulatory galleries, I note that they never include the cover by Art Spiegelman from 1993 to coincide with NYC’s Gay Pride which also alludes to Don’t Ask Don’t Tell.

http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-rYb5dKaFTHs/T_sjK7X86DI/AAAAAAAACFc/hkot05DUbyM/s1600/gaysmilnyer.JPG

It is astonishing that the New Yorker only started including any gay themed cartoons with the arrival of Tina Brown at the end of 1992. But that’s manners for you.

I don’t see how anybody could read the Crumb Genesis and conclude that Crumb was disinterested or that he had nothing to say. He points out that it’s the people who claim to take it very seriously who always want to edit it or give you fishy explanations for this or that WTF moment. He even makes the begats interesting, for crying out loud.

The problem with that New Yorker cover is that a lurid/grotesque sensibility just doesn’t go with a progressive treatment of gay marriage or gender roles. I wonder what they were expecting. When he portrays heterosexual behavior and his own proclivities as disgusting in all his other comics, it’s hard to say he’s singling anybody out, but at the end of the day that cover has to sit alone on a magazine rack.

I thought that what Crumb had to say about Genesis in his endnotes and subsequent interviews was interesting, but it boiled down to, “These are some stories by an ancient tribe of people who lived very primitive and brutal lives. Some may be retellings of even older stories by the Sumerians, who had a less patriarchal outlook.” The illustrations may have implied those points, but such a massive project seemed like a long way to go for them. I’d rather have hundreds of pages of Crumb comics illustrating his own thoughts.

I like what Nate said about Crumb bringing the outside to the inside. That’s why I don’t think you have to share his fetishes to be interested in his sex-themed work–you just have to find his psyche interesting. It’s like he’s drawing his own sex drive more than anything external.

I meant, “the inside to the outside.”

He doesn’t make the begats interesting. Not even a little.

We had a massive roundtable on Crumb’s genesis; don’t necessarily want to go back over it, but if folks want to read the whole back and forth, an index is here.

i disagree; I think he makes the begats not only interesting but touching.

As for that cover, it has charm, truth and wisdom going for it. I see people like that couple every week.

Has anybody noticed that the spiked Crumb cover looks … amateurish? Professional technique is the one thing that the critics never agonize over … nor many ADs, anymore.

Mahendra, maybe that’s the real reason the cover got spiked… the AD said “What’s the deal with these hands? Getoutahere!”

No, the hands are perfectly fine.

The main problem is the heads are too big for their bodies, plus composition in general … reminds me of the sort of stuff one does in one’s first painted pieces in illustration class. There’s a 70s, Dr. Martin’s Dyes+gouache feel to the rendering …

Clearly I’m not sensitive to these things. Mahendra, would you say the problems you see in this image are typical of Crumb’s work? Are they entrenched stylistic peculiarities, or is this image particularly off? I’ve never heard anyone lavish praise on Crumb’s (very occasional) use of color. My favorite color Crumb is the first issue of Mystic Funnies, which someone else colored…

His colour work is not his strong suit … I haven’t seen enough painting (as opposed to coloured pen and ink) but this piece is exactly the way I was taught to paint commercially in the early 80s. It’s a default mode, pre-digital, for making opaque colour art, camera-ready when you have neither the time, money, opportunity nor inclination to learn painting properly. A lot of pen and ink guys are crummy opaque painters (har har) … but then again, there’s Jeff Jones.

The draftsmanship is a bit rough also. Crumb was never a hard-core draftsman anyway, so frankly, who cares.

I’d be very dubious about accepting Hilary Chute’s particular definition of the comics canon as academia’s. Yes, Spiegelman’s Maus is the lazy professor’s keystone for a comics syllabus (just as 1984 and Brave New World and Fahrenheit 451 are the lazy professor’s keystones for a science fiction syllabus), but I don’t think it’s all that common in the more interesting comics syllabi that I’ve seen—certainly not the ones that (unlike Chute) are interested in commercial comics and gutter genres.

I don’t even really like Maus, but I think it’s pretty central, and not just for Chute. Obviosuly people teach other things, but it’s way more influential on art comics than 1984 is on literary fiction.

I wouldn’t deny that Maus is a key text, but it’s not like a comics course is incoherent without it. I don’t teach it in mine: last fall I used Watchman for the 1980s unit, and this fall I’m using Love & Rockets.

My main point here is that the Spiegelman-centric canon has caught on largely because it plays to traditional high-culture academic prejudices about the superior authenticity of realism as well as the rise of identity politics in the 1990s. In other words, it’s a safe, lazy choice.

I don’t think anyone said a comics course was incoherent without it?

Again, I don’t much like Maus, but autobio comics are a really important genre, and Spiegelman is at the center of that. You could see it as safe and lazy in some ways — but you could also see it as a choice that is more open to a non-fandom community. Pointing to genre comics and L&R definitely seems like you’re coming from a fandom place. Kim’s piece seems to be trying to suggest to you that maybe, possibly, your personal preferences don’t have to be a way to stake a claim for pure comicness and sneer at everybody else, you know?

I mean, are you saying you want to see comics in academia as always an insurgent force battling against the staid ivory tower or something? That’s certainly a Crumb-like position, I guess.

Oh, I’m definitely emerging from a fandom place: the first comics I remember reading were things like Thing and Hercules in Marvel Two-in-One or Trimpe’s work on Godzilla. But the arc of my reading over the decades has been away from superheroes: although I still pick up a slew of books on Wednesday, the three most recent comics I read were Sam Alden’s It Will Never Happen Again, Michael De Forge’s Lose #6, and Simon Hanselman’s Tumblr. So I like to think I’m moving toward a more capacious understanding of the medium.

But it’s also true that as someone with a genre background I find the “acceptable” breed of comics study in academic frustrating. Hilary Chute is incredibly smart, a great interviewer, and Graphic Women is certainly an important book. But her ascent to prominence is linked in part to the easy intelligibility and relatively high status of the autobiographical narratives she favors. It’s not much of a challenge to other academics to be asked to read these verisimilar narratives of historical testimony and identity formation–fits easily into the overall dominance of the novel within literary studies.

So in that sense I guess I am taking a Crumb stance (interesting given that I actually don’t like any of Crumb’s comics beyond his work on Harvey Pekar’s American Splendor). But I do actually have a lot of overlap with Chute’s personal canon in my teaching: Sacco’s Safe Area Gorazde, Barry’s One Hundred Demons, and Bechdel’s Fun Home are all regularly on my syllabus. I don’t want a classroom that only plays to my predilection for genre material and my own identity as a fan.

Perhaps another way of phrasing the irritation that made me post initially is that the 2012 Chicago conference is not just to be criticized for the absence of cartoonists of color (Keith Knight’s complaint, coupled with the lack of either Jaime Hernandez or Beto Hernandez on the program) but for its narrow focus on a specific tradition of influence and set of largely non-fictional genres.

Well, that all seems reasonable enough. It was inevitable that the conference couldn’t focus on everything, but pointing out how in particular it was limited seems like a useful thing to do.

Yes, essentially I am in agreement with Kim here.

Well, Chute pretty clearly considers Crumb to be an essential figure in comics–he was a panelist at her conference, and she put the blown cover under discussion on the front of Critical Inquiry, which is sort of bananas. But I rather doubt she ever considered asking Crumb to give that keynote, for obvious reasons.

Spiegelman created comics in academia not because of his centrality in comics courses–though I’m sure he still has that, and I agree w/ Noah that it’s deserved–but because he brought comics into classrooms across disciplines (most notably, IMO, history).

I think Chute’s tendency toward autobio is universally favored, not for its intelligibility, but because English departments tend to emphasize narrative. But it’s curious to me that Rob sees this as related to the dominance of the novel, which is of course fiction. Fiction has a favored status in English depts, IMO, and Rob’s comments on mimesis seem to me to reflect the still somewhat common notion that memoir is somehow distasteful, easy, low, etc.

In any case, Chute has not asked other academics to read anything; she vehemently doesn’t believe in canon, and she doesn’t consider herself as any sort of a model. Hillary doesn’t come from a place of traditional fandom, but her position in conversations like these is that she works on what she likes. I have argued elsewhere (as others have) that the conference’s lack of diversity was irresponsible; it is my position that just because you don’t believe in canons doesn’t mean that they don’t exist.

“I don’t believe in canons; I just believe in endorsing and celebrating artists that people like me already like.” Or something like that, right?

Separate note: One nice thing about the comics canon is that it emerged, piece by piece, among a relatively small subset of creators and critics, mainly outside the bounds of any clear set of culture-capital institutions (or even clear lines of communication and influence). More a loosely tied collection of passionate individuals, often sharing certain comic-autobiographical trends, rarely intersecting with the academy. The U of C just join the decades-old chorus.

And if Maus isn’t central to the comics canon that emerged from this history — in terms of aesthetic influence, critical regard, and cultural/subcultural reach — then I don’t understand what we mean when we use the term “canon.”

Kim, I like autobiography and memoir to the novel because all three are trading in realism, verisimilitude, and authenticity. From where I sit in my English department, I don’t see memoir and autobiography as particularly disadvantaged by their non-fiction status. When I was associate head and in charge of curriculum, I had no trouble from colleagues when I suggested that non-fiction be added to the list of broad genres that comprise our intro to the major (fictional narrative, poetry, and drama). An utter non-controversy.

For me as an instructor, the struggle has been to overcome a stigma against non-realist, non-literary genres and texts. Teaching Maus and Persepolis and Fun Home has never been an issue for anyone in our department; these texts fit nicely into long-established traditions, their comics form notwithstanding. But there was mild controversy about a major authors course on Alan Moore, a colleague is routinely dismissed because she regularly includes J. K. Rowling on her modern British fiction syllabus, and I was once removed from a desired fantasy literature assignment because I was needed on a “real literature” class (actual quote). It’s been made clear to me that a graduate seminar on comics or fantasy literature would be a non-starter–if I fight for it, I’ll probably get it, but I will have to fight for it. Even the comics class I pioneered (the first comics-specific rubric at my school even though comics have been taught in topics classes before) was controversial: an ally on the college curriculum executive committee told me that two members strongly argued against letting trash like comics into a university curriculum.

All this is to explain why I consider autobiographical comics to be a prestige format that has been readily embraced by the academy. They don’t have the stink of the fanboy on them; they’re often affiliated with avant grade traditions and thus confirm established hierarchies of value. Kirby’s OMAC is no less narrative than Spiegelman’s Maus, but I don’t see the former ever receiving the same imprimatur as the latter–and that difference is not simply an issue of artistic quality.

I want to make it clear, BTW, that I am in no way denigrating the authors that Chute finds most compelling and champions in her work. Joe Sacco, Lynda Barry, Alison Bechdel, and Chris Ware are all cornerstones of my class. Nor do I want to come across as dismissing Spiegelman and Maus: from what I’ve read on this site, I think I like it much more than, say, Noah does. Essentially I don’t teach Spiegelman in my comics course for the same reason that I never teach Shakespeare in my survey of early British literature: the authors of Maus and Hamlet don’t need my help in reaching students. Other equally deserving artists (Jaime Hernandez–none of my students have ever heard of him, Christopher Marlowe–same deal) will benefit more from a hearing.

It’s pretty hilarious that college-going, young Anglophones know what Maus is but have no idea who Marlowe was. So much for the meaning of the word canon … I get confused by all of the above commentary but I get the feeling that canon is — in certain quarters — a euphemism for children’s entertainment masquerading as adult art.

I have two secret, commercially insane dreams … one of them is to comix Marlowe’s Tamburlaines. Hats off to Mr. Barrett for putting up with the little blighters.

Hey Rob, with the proliferation of smart people writing about pop culture on the Internet, I think it’s easy for people like me to forget that the high/low divide still exists in many corners of culture. Certainly at the Comics: Philosophy & Practice conference I was SHOCKED that it still seemed to be such a big deal. With cartoonists, it strikes me as largely a generational concern; I just don’t hear young people talk about it that much. It makes me wonder if some of the battles you describe are going to ease up over time, as younger profs who aren’t so vested in the high/low binary age up. Hope so.

Uh, same goes for “children’s entertainment” and “adult art.” Oh lord I can’t even.

Kim: things are definitely shifting. Two profs were opposed to my comics course when I proposed it in AY 2012-13 … but the course passed muster nonetheless. When I started at my university back in AY 2001-02, there’s no way it would have even necessarily cleared the department, let alone the college. A great many of my graduate students do great comics work: one has published in, among other venues, that great Mississippi volume on Chris Ware, and another produced an excellent Swamp Thing article. I also just read a colleague’s draft essay on queer Latino superheroes that’s on its way to be published. So the scene is much, much better.

But it’s also true that the Internet discussion of comics is so much richer at this point, precisely because there’s been no gatekeeping to overcome. There is criticism as good as (say) your article on autobiographical comics and fact/fiction, but it’s relatively thin on the ground at present. Same thing with the debate here and at TCJ on EC Comics: the academic scholarship on EC is still playing catch-up in terms of raw numbers of meaningful pieces.

And now Jeet Heer and Charles Hatfield (among others) will show up and prove just how outdated my info is. My only defense is that I’m a neophyte in this field. :)

Qiana Whitted (who writes here often) is working on a volume on EC Comics now, I believe.

“Essentially I don’t teach Spiegelman in my comics course for the same reason that I never teach Shakespeare in my survey of early British literature: the authors of Maus and Hamlet don’t need my help in reaching students.”

I understand the sentiment, but am a bit skeptical. My own sense is that college freshman (to say nothing of college graduates) don’t necessarily know a ton about anything. Probably most have been taught some Shakespeare in high school, but how much they got from that would I suspect be an open question — and my guess is that most have no idea what Maus is.

Not that I really care if they learn what Maus is (or what L&R is for that matter.) I’m just saying that while the old standards may seem boring and inevitable to the teacher, I suspect most students know as little about them as about less canonized works.

Oh sure, Noah, but then again I try to teach only the things I like (since I have found that students can tell when you’re teaching something you’re “meh” about). And I’m “meh” about Shakespeare and Spiegelman compared to other authors of equal quality from their respective periods. No one is certainly getting stuck with crap if they’re asked to read Doctor Faustus and L&R instead of The Tempest and Maus.

mahendra says: “It’s pretty hilarious that college-going, young Anglophones know what Maus is but have no idea who Marlowe was.”

Honestly, Mahendra, I share your … what is it .. concern? dismay? bemusement? All of the above? But, yes — ijn a way that has little to do with Marlowe per se.

Indeed, I’m glad that I went to college and grad school in the days before there were classes in comics.* Because I would have taken them, to my detriment. I didn’t need courses in what I already knew — to strengthen (or even challenge) those extant prejudices, tastes, biases. I needed — NEEDED — to take classes in what I *didn’t* know. I needed to be bad at things, to bump up against the limits of my experiences and abilities. Milton, yes. Maus, meh.

*For true, I took a seminar called “Word & Image” with W.J.T. Mitchell. Great class. Didn’t talk about comics once. Even as a comics teacher, I’m not convinced anyone really needs exposure to the greats of the medium, or the not-so-greats.

I took that same class, Peter. Could’ve used some McCloud IMO.

Anyway it’s telling that a conversation about comics canon has somehow turned to centuries-old British literature. Powerful testament to Rob’s points about the academy.

At least we’re not arguing about the Crumb cover any more!

That Crumb cover depressed me, as did his Genesis. Perhaps the “GN Canon” in academia is related to the phenomenon of remedial English for undergrads? One thing’s for sure, when I submit GN proposals to the vast majority of North American publishers, multi-syllabic words are a no-no, no matter the intended reading age. And complicated visual puns and such-like, ditto.

The business community bitches mightily about the crappy quality of personnel intake while they proft mightily off the dumbing down of the same.

I like the cover. I bet Crumb was influenced by the absurdity of an argument like the one made by, e.g., U.S. District Court Judge Martin Feldman in support of Louisiana’s gay marriage ban:

“For example, must the states permit or recognize a marriage between an aunt and niece? Aunt and nephew? Brother/brother? Father and child? May minors marry? Must marriage be limited to only two people? What about a transgender spouse? Is such a union same-gender or male-female? All such unions would undeniably be equally committed to love and caring for one another, just like the plaintiffs.

First of all, this kind of worry over how to people’s genders ought to be policed — so that the folks in change can decide whether they’re legally allowed to marry or not — is absurd, comical, and square. It leads to absurd situations like the one described in this comment on metafilter (“I’m having facial surgery later this year and I’m just going to hang on to the surgeon’s letter so I can change my birth certificate or not in the future as needed”). Having rules about which consenting adults can and can’t get married means you need a whole legal apparatus just for checking whether this situation or that situation falls under the law.

Probably more should have been done to highlight the couple over the clerk – I think they should have had both and clasped together and been posed facing each other, not at all facing/concerned with the clerk since legally speaking, they’re in the clear. Maybe the clerk, instead of looking alarmed at only the MTF half of the couple, could have been furrowing his brow over various gender inspection forms so as to refocus on the comic on his sense of bureaucratic panic.

Crumb might be out of touch with this but so are the people who make the laws, in other words. The execution could be better but there’s some merit to basic concept.

Pingback: Clickable « DOMINIC UMILE