After this weekend’s post on whether video games can be art (and/or good art), I thought I’d check out Depression Quest. The game is somewhat infamous because designer Zoe Quinn’s ex publicly attacked her on some message board or other, and then other folks joined in because (as far as I can tell) they hate women and possibly because the idea of a video game in which you don’t shoot people frightens them? I am unafraid of video games in which you don’t shoot people, though, so I went ahead and played it.

Depression Quest has an ambitious concept, especially for a video game; it’s intended to give you a sense of what it’s like to live with depression. It’s a text adventure, which positions you as a middle-class, college-educated alterna-sort, of indeterminate gender, working a minimum-wage job and struggling to get through the day. You have a more outgoing girlfriend, a loving if not especially sympathetic mom, a more successful and friendly brother, some online friends and some actual physical friends. The game wends along, describing your anxiety, neurosis, and general inability to cope. This is a typical passage.

“A couple hours later the two of you find yourselves in a familiar position: on the couch, watching comedy shows on Netflix, a box of pizza open on the coffee table in front of you. As you look across the couch at her, you start to feel anxious. You feel bad about effectively forcing the two of you to stay in tonight, again. While you are always appreciative of your partner’s efforts to take your feelings into account and help make sure you’re socially comfortable, you sincerely worry that you’re holding her back from enjoying a more fulfilling relationship.

So…is it art?

I would say that yes, absolutely, Depression Quest is art. It’s true that its goals are more social and educational than purely aesthetic — but lots of art works towards social and educational goals (The Jungle; The Handmaid’s Tale; James Baldwin’s essays, and on and on.) The game works to create empathy and understanding, and to create and examine emotional states. Those are all recognizable aesthetic goals. It’s definitely art. The question, though, is whether it’s good art.

Here the answer is a lot less certain. Again, I’m impressed by the concept; the idea of using a game to explore mental illness is exciting, and using interactive fiction seems like an intuitively promising way to do so. Mental illness is difficult for people to sympathize with because for folks who aren’t mentally ill it’s hard to put yourself in the brain of somebody who is. Using a game to force that identification, to put you in the place of someone making those choices, seems like it has the potential to create empathy and understanding in a way that less immersive art forms, from novels to film, do not.

Again, that’s the theory. The practice doesn’t exactly hold up though. In part this is because, as it turns out, games are not as immersive as fiction — or at least this one isn’t. Quinn deliberately leaves a lot of the game details open-ended. Your minimum wage job isn’t specified; the project you’re working pursuing on your own time isn’t specified; even your girlfriend is vague around the edges — she offers sympathy, or retreats, or wants sex, but there’s never a descriptive passage which makes her come to life as a separate, individual character, the way there would be in a good novel. This lack of detail is undoubtedly deliberate, it’s meant (like your own non-specified gender) to make the story resonate as widely as possible.

For me, at least, though, it just made the scenario seem schematic and uninvolving. Why do I care what my girlfriend thinks when she isn’t a person? How can I feel how numbing my job is if I don’t even know what I’m doing for a living? The world is too indistinct for me to care about engaging with it. The character I’m supposed to be simply isn’t vivid enough for me to care about him or her, even if he or she is supposed to be me. (The moody anonymous Somber Piano Music is perhaps meant to bridge this gap. It does not.)

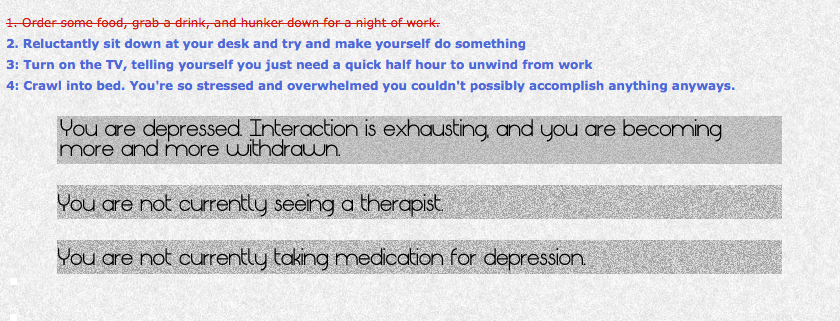

The problems only get worse when you have to make choices. At each turning point, Quinn gives you a number of alternatives, as in Choose-Your-Own Adventure books — but in some cases, the choices are crossed out, because, when you’re depressed, you often can’t do the thing you know you should, whether it’s loosening up and sleeping with your girlfriend or telling your mom you’re really sad and need help.

It’s a clever conceit…but again, not clever enough. The limited choices are supposed to give you a sense of what it is to be depressed — but the problem is,you still have choices, and it’s easy to figure out what your best remaining options are. Adopt the cat, see the therapist, take your meds, try to be as outgoing and honest and open as you can. Pick the right options, and things turn out more or less okay. That isn’t what it feels like to be depressed, I’m pretty sure — and it’s also misleading, insofar as (from everything I’ve heard from friends with mental illness) not all therapists are good thereapists and getting a bad one can be miserable, and meds are unpredictable and can make things worse in various ways if you’re just a little bit unlucky with your body chemistry. Despite those crossed-out choices, Depression Quest makes depression seem like something you can choose your way out of. It makes depression look easy.

The very things that seem like they might make Depression Quest especially effective — the open-endedness, the interactivity — instead make it banal and emotionally unaffecting. In contrast, art which is more specific and more controlled — like, say, Charlotte Perkins Gillman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper,” or the brutal suicide scene in Sooyeon Won’s Korean comic “Let Dai” — are a lot more engaging, and a lot more harrowing. Even the infamous depression sequence in Twilight, where Bella just mopes and mopes and mopes, seems like it works better — it feels tedious and frustrating and you just want her to get over it and she doesn’t and it goes on and you want her to get over it and it goes on — you’re trapped with her, this person you don’t really like who is behaving irrationally and won’t stop and there’s nothing you can do. You can’t make the best choice, or the second best choice, or any choice. You’re in a particular consciousness that isn’t working right, and there’s no way out. In Kafka, say, time slows down and expands, till you’re dragging on interminably, pulling an ugly insect body behind you. The specificity of the experience and the lack of options are precisely the point; as a reader, you’re nailed to this particular self and its decisions, or lack of decisions — your own interaction with the story can be seen or read as a metaphor for the experience of mental illness.

This makes it sound like books, or comics, have an innate formal advantage over games in the depiction of, or examination of, depression. I doubt that’s really the case; there are plenty of crappy depictions of mental illness in non-games, after all. I do think that Depression Quest’s aesthetic goals and its formal choices end up being at odds with one another. The game is a good idea, and it points in some interesting directions, but on its own terms, as art, I think it’s mostly a failure.

____

Edit: Please note that this thread is not an invitation to talk about Quinn personally, or Gamergate, or etc. The post is about Depression Quest and video games as art; comments that are off topic will be deleted.

Dys4ia, the game I posted last time is shorter, simpler, and better (ignore the ads filling up the page).

Picking up the conversation from the previous post, no site can the HU of video games, because most writers of video game criticism are young people struggling with their lives. They often lack the financial stability to keep writing. That’s why many have chosen to use Patreon to fund their writing, a fact that has become another target of attack in this ridiculous internet riot.

Okay; so, I just deleted a bunch of comments (including one of mine.) We are not having a discussion here about Quinn personally, or Gamersgate, or any of the related issues. This thread is for talking about Depression Quest and video games as art. If folks go off topic, I’ll delete it, and/or shut down the thread if it gets too bad.

Edit: I’ll probably have a relevant link tomorrow on the Saturday roundup, so folks can talk about it there and then if you all feel like you want to do that.

In Japan there’s a whole genre of visual novels which are basically long choose your own adventure games with pictures, audio and anime style graphics. They tend to have very little interactivity, just a few choices at key points in the story, and can be as long and detailed as a novel.

They are very much niche genre products (with anime aesthetics), and many of them are adapted into anime and manga. A recent popular one which became an anime is Steins:gate. It was big enough that the game is available in English.

http://steins-gate.wikia.com/wiki/Steins;Gate_(visual_novel)

I mention this because the question of whether video games are art is silly to me. It’s like asking if novels are art. Sometimes video games are novels.

An interesting take, Noah. Your complaint is actually the opposite of the common one about various games — that there aren’t enough choices, that you’re too constrained, and any sense of freedom is illusory.

I don’t think, tho’, that you can assume the goal is to get yourself out of depression. That’s probably the normal response but…when I played it, I definitely went the other way — choosing the more depressed options. I haven’t checked this, but I think that when you play it that way, your options become even more constrained; more of them get crossed out. Playing it that way turns it into a kind of depression simulator, which is (take it from me) a much more lifelike experience.

I did think of that…and tried going through and making the worse decisions too (and yes, I think more and more choices get crossed out.) I feel like you’re still in control though — you’re choosing to be depressed to see what that feels like/how it works in the game, which seems again like it’s maybe too easy.

I do think the Bella depression sequence was kind of in retrospect especially interesting in Twilight. People really, really hate that part of the book — and I think that’s often people’s reaction to depressed folks; they’re seen as frustrating, and as not trying hard enough, or as morally flawed.

You’re right that there is that dissonance. In any game where you have an avatar, there’s always some difference between the motivation of you, the player, and you, the avatar, even if it’s just that you’re playing the game and thus have the additional motivation (generally) to have fun. But depression being, among other things, a disorder of motivation, there is this yawning gap between player and avatar here (hard to see how it could be otherwise, and still be a game — a game entails some degree of choice, however small — maybe you could do it fumblecore).

Maybe it’d be better to see that difference as a feature rather than a bug? I’ve had that kind of career-ruining, life-destroying depression and, yeah, it didn’t feel like I even had those “correct” options available, or any options even to roll over in bed. But that’s something that might be useful to somebody suffering from that kind of episode — that distance between you and the avatar means, maybe, that you can see the better options that you can’t see in your own life, precisely because you’re not caught up in it? Maybe you could get some insight into, objectively, how fucked up some of that style of thinking is?

Relatedly, you might see the game from the perspective of a third-person, non-depressed person — seeing, on the one hand, the “correct” choices that are so obvious, and then, on the other, the self-destructive choices that depressed people routinely make…so, not so much, “this is what it’s like to be depressed”, as “these are the kind of thoughts and choices for depressed people” (when you make the bad choices)…

Aw, I was going to make a dumb joke about Quinn not offering you enough sexual favors, but that looks like a method to just get my comment deleted (and probably justly, since I doubt I’m the only one who made the joke). Instead, I’ll try to offer something of possible relevance:

I haven’t played Depression Quest, but it sounds like an interesting attempt, if one that’s less immersive than it could be. The idea that more and more choices get crossed out the more depressed you get seems like a good one, but to really simulate depression, it probably needs to be more banal and repetitive, like the Twilight example Noah gives. It’s difficult to get across the pain of mental illness, but the idea of repetitive thoughts and anger at yourself coming at a non-stop pace, with no way to stop it and no end in sight seems like something you would want to attempt to depict. Or maybe that’s just my own experience talking…

Really, mental illness is pretty specific to each person, so what sounds like an attempt to genericize the experience and make it seem like anybody could plug themselves into the narrative might be what defeats the game. I think it would be better to make it specific, and really put the player inside the head of somebody that seems like a real person who is going through this experience.

As for the idea of “choosing your way out of depression”, that’s not a terrible metaphor; you could even say that it’s like a game in real life, one that you could theoretically win or lose (live happily or commit suicide). Living with mental illness really is about making the right choices (although I suppose that could be said about life in general…), but as Noah said, those choices aren’t always up to you, and there are no universal right choices that will work for everyone, which goes back to the idea of specificity.

So, in conclusion, I should probably play this game so I can know what the hell I’m actually talking about rather than just discussion stuff secondhand. I hope everybody enjoyed my irrelevant nattering.

Jones, I think the things you talk about — like playing with the difference between player and character — are things that could be used to good advantage. I don’t think DQ quite manages it, though, unfortunately.

Chris Onstad drew a decision-making flowchart for his depressed character Roast Beef. That’s more like the “choices” you have when you’re seriously depressed; you could make a game out of that…

There is another game about depression that you might find interesting and which, I think, addresses a lot of your complaints about DQ. It’s called Actual Sunlight. It presents a more fleshed-out world (by simply being a lot more visual) and it has the opposite approach of DQ’s with regards to choice. While the game offers the player choices, the character will rationalize his way through them, always ending up in the more damaging situation.

But I think that doing so it takes a way too bleak and hopeless point of view. Even if the creator insists that the game is not the story of depression, but of a specific depressed individual, it’s easy to see the it as presenting depression as something that cannot be fought, that removes all agency from the individual from the very beginning.